di Marco Maculotti

We continue the discussion previously developed, taking it from the connection that we have seen to exist, in ancient traditions, between the period of the "solstitial crisis" and the belief in the return of the souls of the dead to the living. The connection with the underworld / underworld and with the Kingdom of the Dead seems, as we have seen, to be recurrent for these deities that we have defined as 'of the Winter Sun' [cf. Cernunno, Odin and other deities of the 'Winter Sun'], at the same time gods of fecundity and also linked to the underworld and, therefore, to the deceased.

We have already seen that the Celtic Cernunno, in addition to being a god of nature and time, is also considered an underworld deity, especially as regards his psychopomp function, as a companion of the dead in the afterlife: a mercurial aspect that in tradition Nordic is also found, as we have seen, in Odin / Wodan, from which in fact derives the day of the week which Latin belongs to Mercury (Wednesday= “Wodan's days"). Likewise, in many traditions from all over the world there are numinous figures connected both with fertility and with the Underworld and the Underworld, starting with the Mediterranean Lord of Hades Pluto, among whose symbols there is the cornucopia (*krn), conveying abundance, fertility, wealth.

Turkish-Mongolian and Siberian tradition: Erlik Khan

We begin to analyze, first of all, the shamanic-type cults of the Turkic-Mongolian and Finno-Ugric populations of Siberia and North-Eastern Europe, in which the shaman, after having descended in ecstasy into the underworld, can experience the 'meeting with the divinity to whom its dominion is delegated: Erlik Khan, god give cervine horns (and which also “uses horns as weapons ") and for this reason assimilated to Kernunnos. It could be assumed that the origins of this mythical horned god, who manifests himself as Erlik Khan in the Finnish-Siberian shamanism and as Cernunno in the European one, are to be found in a remote and forgotten past, in cults and rites of which no trace has been lost, but which we have proved to be common to the whole Eurasian area [cf. Metamorphosis and ritual battles in the myth and folklore of the Eurasian populations] and whose origins could even go back — it is believed — to the Upper Paleolithic.

Erlik Khan is first of all considered the clan ancestor, the progenitor of humanity and above all the prototype of the first dead, exactly as, in the Indian tradition, the Vedic Yama, which — coincidentally — was also portrayed with deer Horn, as well as its Indo-Iranian equivalent Yima [Lot-Falck, pp. 47-55]. The functional characteristics of Erlik, in short, suggest his lordship over the underground kingdom of the dead (which is also amply confirmed by the shamanic tradition of these populations), which first Erlik reached. And nevertheless it is believed that Erlik - as well as the tutelary deity of the dead - is also a true 'god of burgeoning power': he is distinguished, in fact, mythically, as the one who created barley and to whom - in addition to dark places, muddy lakes such as the one with the "nine eddies", to the dark districts full of cliffs and black sand— green valleys with young groves are pertinent [Chiavarelli, Diana Arlecchino and the flying spirits, pp. 82-3], which the shaman can also reach during the ecstatic trance and whose description has striking similarities with the so-called 'Josefat meadow' in which, according to the confessions of the accused of witchcraft in the medieval inquisitorial trials, they reached in spirit, with a technique therefore similar to that of the shamanic practices of the Siberian area [cf. The Friulian Benandanti and the ancient European fertility cults].

Narto-Ossetian tradition: Barastyr

The Nartis and Ossetians, descendants of the Scythians and settled in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, also have such traditions. It is believed, for example, that post-mortem the soul “reaches a crossroads of three roads: the two on the side lead one to heaven, the other to hell; the middle one must be preferred: the dead man who takes it arrives at the place where, among the Narti assisi, thrones Barastyr, king of the Dead ". Here we find an important theme for our research: traditionally it is believed that the soul after death must take a path to the detriment of others and that only those who know the right path can reach the afterlife of the god. This is a point of primary importance to keep in mind. The knowledge of the heavenly ways, often represented in the form of rivers (think, for example, of the four infernal rivers of Greek mythology) is essential to arrive in the presence of the god, in a state post-mortem preferential to the undifferentiated mass of non-initiates. Kowalewski derives the figure of the ruler of the dead Barastyr from Mazdeism, putting him in relation with the Indo-Iranian Yima, equivalent to the Vedic Yama. However, Dumézil, who quotes him, is of the opinion that Barastyr is a specifically Ossetian god, deriving, in any case, from a common mythology to which the afterlife of Vedic India also belongs, which, in the author's opinion, is more close to the description of the Ossetian Underworld [Dumézil, p. 254].

Dacian-Geta tradition: Zalmoxis

Turning now to the beliefs of the Dacians / Getae, belonging to the ethnic family of the Thracians, they believe that the initiates, after death, reach Zalmoxis, who is configured as a psychopomp god of the mysteries who mythically first reached the afterlife, and for this reason welcomes his followers when they arrive there after death. Similarly then to the Akkadian-Sumerian Enki or to the Indian and Iranian Yama / Yima, it could be said that he he was the first to trace the path that unites this world and the next, the invisible one, the afterlife or 'kingdom of the dead', an underworld that in reality - as we will see - should not be understood as merely geologically "underground", but rather as abysmal in the cosmic-dimensional sense, as a dimension other, almost a 'world upside down' of the world of the living. In this perspective, it could be said that there is a reality superficial (exoterically Earth, sublunary: the 'world of the living') and one occult, hidden under (o behind) the superficial one (and therefore exoterically defined chthony, underground, hell and not infrequently associated with the selene dominion: the 'world of the dead').

Returning to the figure of Zalmoxis, some compare him with Zameluks, Lithuanian god of the earth, others with the name Zamelo, found in some Greco-Phrygian funerary inscriptions in Asia Minor, probably related to the Thracian zemelen ("Earth") from which also Semele, lunar-telluric goddess, mother of Dionysus, of whom we have already spoken in previous article. It should be noted that all these terms derive from the Indo-European root *g'hemel (“Earth, soil, belonging to the earth”) which brings us perfectly back to the context of our study, that is to say the dichotomy terrestrial / inferior, telluric / chthonic, generation / death, living / dead, vegetation / spirits of the ancestors. Being xais we can translate a Scythian term for "lord, chief, king" Zalmo-xis as "Lord of the Earth" [Eliade, Zalmoxis, p. 46], "King of the Soil" (and, perhaps, also del underground, understood in the esoteric sense of reality under reality).

Nonetheless, even with regard to this mysterious figure there are the usual, apparent contradictions, deriving from the fact that its functional area has never been identified with certainty. Some scholars, including Clemen, clearly saw in Zalmoxis the "Lord of the Dead", but in the opinion of others, including the famous Thracian historian Russu, "the semantic value of the zamol- it is' the earth ',' the power of the earth 'and Zalmoxis can mean nothing other than the god of the earth', personification of every form of life and of the womb in which all men return "[Eliade, Zalmoxis, p. 47]. Here too, therefore, the dichotomy that we have already traced, eg. in Cernunno and Dionysus, between 'god of the earth and vegetation' and 'god of the dead' and of the 'underworld'.

Zalmoxis as "initiator to the Mysteries"

Unfortunately, the few joint fragments do not allow us an optimal understanding of the figure of Zalmoxis: it is believed that the divine name, as often happens, was in times closer to us used in reference to historically existed figures particularly influential in the field of culture. sacred of the Getae; in other words, at various times Zalmoxis was called the wisest priest in the temple, or a particularly skilled shaman. According to Herodotus, a Thracian named Zalmoxis imported the Pythagorean doctrine on the immortality of the soul among the Getae, and to prove it "he had an underground dwelling built for himself and when this was completed he went down there and lived there for three years. The Thracians missed him and mourned him as dead, but, in the fourth year, he appeared to them again and so was proved what Zalmoxis preached".

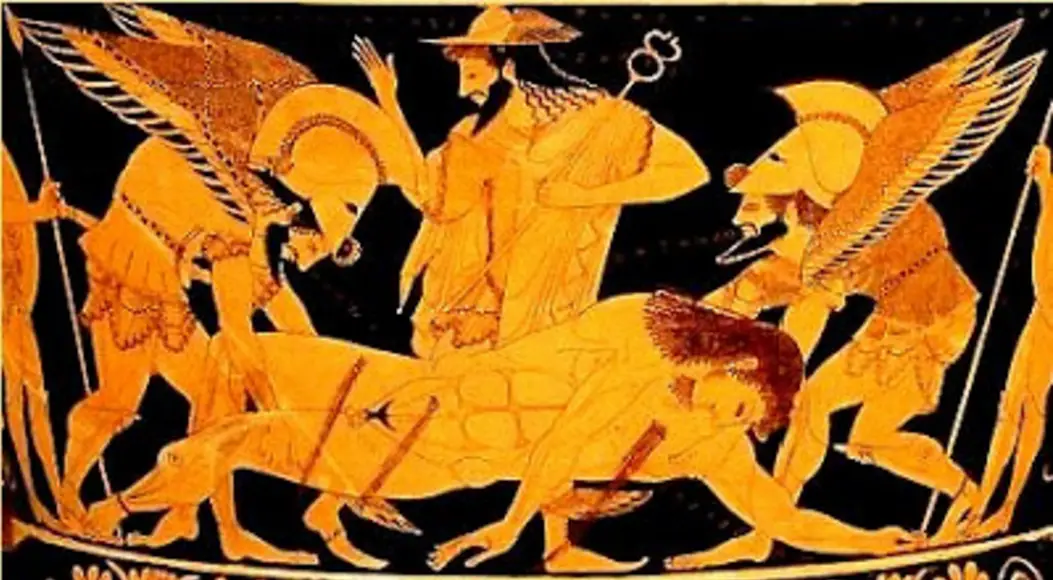

We are therefore in the area of topos mythical of katabasis (descent into the Underworld), of apparent death and resurrection that connects now divine figures (Adonis / Tammuz, Odin / Wotan hanging on theYggdrasil, Baldr and Freyr, Osiris torn to pieces by Seth who rules inLied, Dionysus dismembered by the titans and then miraculously reborn from the lightning bolt of Zeus) now human but in some way considered superhuman (Orpheus, Zalmoxis, up to the most recent motif that sees Jesus Christ as the protagonist in the mythology who, following death on the cross , descends into hell and then rises again after three days). You could say they like these deities in illo tempore have discovered the way to the afterlife - we will have the opportunity to speak more about this later -, so every initiate and adept must work his own catabasis, personally descending into the abysses of his being to look for the solution to the mystery that lies behind the apparent duplicity existing between Life and Death: only there will he be able to find the way that was discovered, in illo tempore, from the god, prototype of the first dead and re-born. After a ritual death, equivalent to that mythically recognized to the tutelary deity, the initiate comes back to life as another person: he considers himself "reborn", and having already died, he will no longer die at the time of death, but also will reach the god in the afterlife. I'm from Walter Friedrich Otto [cit. in Kerényi, Dionysus, p. 136], the following words:

Whoever generates something vital must sink into the primordial abysses, where the powers of life dwell. And when he re-emerges, there is a flash of madness in his eyes, because down there death coexists with life.

With several words, Emanuela Chiavarelli [p.121] enunciates the same principle of close correlation between life and death:

Dualism within divinity is as inevitable and necessary as life alternating in the game of becoming with death. If the polarities ceased to oppose each other, the circulation of the same vital flow would be blocked. But one is complementary to the other: in the winter-underworld, home of Hades, king of the dead, the mystery of plant life is concealed. The «Child of Light» of the Eleusinian Mysteries, symbol of the eternal Zoe, will be born in the abyssal caves of Hades.

Deity of the dead and deity of the Mysteries

It should be noted in this regard that Eliade does well to underline how the fact that the adepts reach Zalmoxis in the afterlife does not necessarily lead to the recognition of Zalmoxis as 'Sovereign of the Dead'. In fact, in his opinion, it is necessary to distinguish the deities of the dead from those of the Mysteries, the former governing all the dead without distinction, while the latter admit only the initiates to them.

Nonetheless, often the distinction between the two areas appears blurred, as for example. as for Odin, who in the Nordic tradition is at the same time god of mysteries (as god of prophecy and magic) and god of the dead, and yet not of undifferentiated mass of dead, but only of those who passed away on the battlefield, invoking his name. Yet, such a 'selection' did not prevent the Anglo-Saxons from representing Odin in medieval times as the conductor of the aforementioned 'wild hunt', that is to say at the head of a ghost procession of dead spirits, ghost animals and demons: now lost , following the conversion to Christianity of the Nordic populations, his value as a mystery god, his dominion is now recognized over a generic group of dead, sometimes even seen as damned, and even animals and demons, thus derailing the image of he who was the ancient 'Father of the Æsir' towards demonic tracks unthinkable only a few centuries earlier.

But the point here is above all another: ancient evidence and recent studies allow us to identify a group of very ancient divinities believed to be Lords of the Afterlife, who were the first to discover the way to the Other World. Often, as we have seen speaking of Zalmoxis, this knowledge allowed the initiate to reach the court of the god, postmortem, in a kingdom out of time, in which one does not age and no longer dies (keep this in mind for the continuation of the discussion). These deities (Osiris, Enki, Yama / Yima) who they were the first to discover the way, constitute an ancient nucleus common to the greatest archaic civilizations, namely the Egyptian, the Sumerian-Mesopotamian and the Indo-Arî, authors of the See.

Osiris, Enki, Yama: "those who discovered the way"

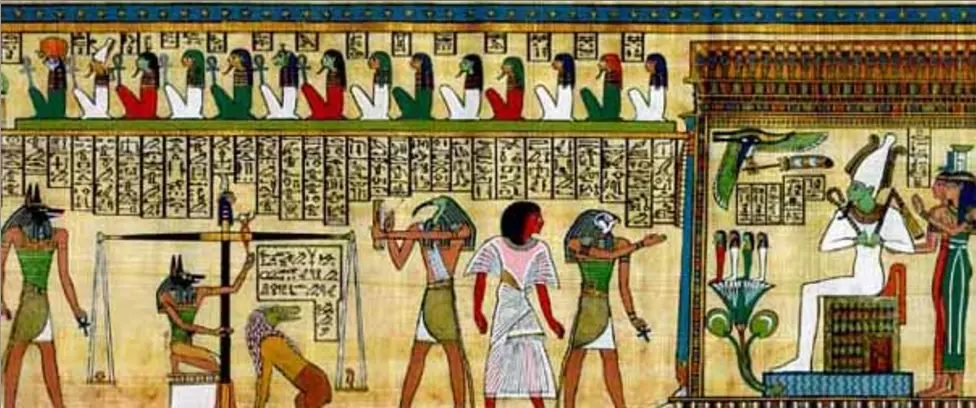

The whole Osirid tradition, extensively treated by many authors and not of particular relevance here, cannot be reported here; we limit ourselves to highlighting some attributes of the god, starting from the fact that he was considered "king for ever in the" Fields of Yalu ", in the" land of the sacred Lied»Beyond the« waters of death », located in the« far West »” [Evola, p. 247]. Similarly to Zalmoxis, therefore, Osiris was the first to reach the "Fields of Yalu" and the "land of the sacred Amenti", that is to say the afterlife, theother world. Osiris arrived there aboard the "Ship of the Dead" and, it can be said, he paved the way for all those destined to follow it later. For this reason, after Seth's death, Osiris ceases to represent the divine generating function to become god of Amenti, that is to say of the afterlife, the Judge of the souls of the dead. During the trip post-mortem, the soul travels the beaten path in illo tempore from Osiris, responding to the divine powers that he encounters during the journey with the formulas contained in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

The same as Osiris for the Egyptians, for the Arî Indians was Yama, which Charles Malamoud [The solar twin, p. 12] defines "god of death, king of the dead, but also tutelary deity of the order that regulates relations between the living and between generations". In Rg Veda (X, 14, 1-2) he is defined "he who followed the course of the great rivers [cosmic], who first discovered the way (...) the gatherer of the people". In the'Atharva Veda (XVIII, I, 50) it says:

Yama was the first to find a path for us; that is not a pasture that can be taken away; where our first Fathers went, there (go) those who were born (of them), each along his way.

He, continues Malamoud [p. 29] chose to die and this decision made him "the first being who dies, the first of mortals": he "explores the path that leads to the afterlife", hence his title of "ruler of the ancestors". His death occurred in illo tempore “It is not a disappearance, but an inauguration”. The French scholar distinguishes Yama from the other Vedic gods, as he alone [p. 32] “he spontaneously placed himself, together with the human generations, in non-immortality, distinguishing himself from the (other) gods. Nevertheless he is a god, constantly designated as such in Vedic prose, and men aspire to a form of survival that must come to them from Yama". We underlined this last sentence as extremely significant when connected to what Herodotus wrote about Zalmoxis: just as his followers yearned to achieve a form of immortality post-mortem, which the god had reached first, so the Indians of the Vedic period trusted in Yama to achieve the same kind of survival, because it was Yama himself who discover the way first.

Canopus and the South Celestial Pole

We have seen how Osiris rules over Amenti, in the same way that Yama rules over the homologous “seat of the Rta”. A third is equivalent to these two places of the myth, in another archaic tradition: the Eridu of the Sumerians in which Enki / Ea dominated. We know that the Sumero-Mesopotamians called the star Canopus with this name, that is to say the cd. "South Celestial Pole". Well, the fact is particularly curious, as Plutarch [Isis and Osiris, XXII] informs us that Osiris was called "helmsman Canopus", because it was handed down that he was transformed, after death, into the star of the same name. We have already said that this was called by the ancient Sumerians eridu and considered the abode of the god Enki / Ea / Enmešarra, variously named "Lord of the Order of the World", "Lord of the Universe", but above all "Sovereign of the Underworld" as well as "the one who has weight in the underworld" [Santillana and Dechend, Hamlet's mill, p. 314] (cf. these epithets with that, attributed by the Christian tradition to Satan of Princeps huius mundi).

Indeed, it should be noted that in the ancient astro-cosmogonic wisdom the kingdom of the dead was always placed in the south, in contrast with the Uranian regions, the Old Testament "Upper Waters". The star Canopus, in particular, was considered the South Celestial Pole, that is to say the portion of cosmic space below: symbolically, it can well be said that this portion of the sky represented the Abyss for the Ancients, so much so that in Mesopotamia it had the name "Star-yoke of the sea", where the "Star-yoke of the sky" was alpha-drakonis, primordial North Star [Ibidem, p. 331].

This tradition of considering the Celestial South Pole as the cosmic Abyss or lowest point of the Underworld (and therefore of the Underworld), ruled by a dethroned primordial god (Enki, Osiris, Lucifer) is widespread: even in China, there are numerous legends about "Ancient Immortal of the Celestial South Pole" (that is to say Huang Di, the Yellow Emperor associated in the Chinese astrological tradition with Saturn), as well as on the various "Sleeping emperors in mountain caves"[Ibid, p.349]. With this last mention we connect to the legends that claim that Saturn / Kronos, after being ousted by Zeus, was thrown by the latter into Tartarus (the Abyss of Greek mythology) or, alternatively, was placed in a region outside of time (i.e. in a extra-temporal dimension, from there governing precisely on the patrols of the cronos) in the extreme north on the island of Ogygia or in the extreme west on the island of the Hesperides or - according to the Celts - on the northern White Island of Avallon, where he lies in a state of comatose sleep, awaiting the return of the golden age [cf. Apollo / Kronos in exile: Ogygia, the Dragon, the "fall"].

The "King of the World"

It would also be interesting to say something about the traditions of Asian origin concerning the mythical subterranean and extra-terrestrial kingdom variously called shambhala o Agarttha, equally governed by an inferior sovereign, the "King of the World", who administers it with the utmost wisdom, just as the whole world of the living is equally subject to his dominion. By proposing to explore themes in the future in such a way that now they would lead us too far, we refer you for the moment to the Guenonian work The King of the World or to the previously published extract of F. Ossendowski [cfr. The Underground Kingdom (F. Ossendowski, "Beasts, Men, Gods")], another fundamental text for the in-depth study of the question under consideration.

The Abyss of the Cosmos

Starting from the underworld, we have ascended to the heavens. Epper not to the Uranian skies, of pure Olympic light (North Celestial Pole; northern cosmic region; Ursa Major's chariot, traditionally linked to the Seven Rishi), but to the abyssal ones, in the realm where Osiris, Enki and Yama judge and govern the souls of the dead. It could therefore be said, with good reason, that far from ascending we have gone even deeper: behind an idea of purely telluric-chthonic depth, a much deeper dimension seems to be hidden in the wisdom of Myth and Tradition, much more abyssal, and I will nevertheless not in a physical-material sense (the subsoil), not on this earth: but in the heavens, in the cosmic Abyss. In Hellenic mythology, this abyss is called Tartarus: in Phaedo (111e-112b) Plato speaks of this place as an abyssal dimension, not underground in our world but rather superimposed, probably alluding to its extra-temporal dimension (Avallon, the Island of the Hesperides, Ogygia):

One of the chasms of the earth is particularly large and pierces the whole earth from one side to the other. Homer speaks of it when he says "far away, where under the earth is the deepest abyss". It is it that he elsewhere and many other poets have called Tartarus. In this abyss all the rivers converge and from it again flow: each becomes such as it is made by the quality of the earth through which it flows. The cause of the flow and confluence of all the currents is that this water has neither bottom nor base.

Plato is very skilled in using geological metaphors to describe higher esoteric truths [cf. Kingsley, Mysteries and magic in ancient philosophy], which only initiates would have been able to grasp. It is clear, in fact, that the inferior rivers of Hellenic mythology cannot be understood as underground physical streams, nor can Tartarus be considered a particularly large chasm that physically opens up underground. It can rather be said that environments of this kind (the undergrounds in the Egyptian pyramids, the xenote Mexicans, the various "caverns of the Sibyl" and the innumerable "Gates of the Underworld" of ancient folklore) were consciously chosen by the mystery brotherhoods as ideal places to carry out rituals of a chthonic-initiatory character and where to adore the underworld deities. There was a tendency, so to speak, to see in the image of the subsoil a cosmic archetype, higher and more pre-human: the cosmic abyss from which all souls came, and to which all were destined to return.

Think, once again, of the mythical images of descent into underground places from Zalmoxis to Christ et similia; now put what has been said in relation to that abyssal cosmic region (Amenti, Sede di Rta, Eridu, Tartarus) which was unanimously considered the seat of the god of the dead, of the clan ancestor who, who died first, he had discovered the way to go, whether it was called Osiris or Yama / Yima or Enki / Ea. There is no longer any doubt, at this point, that this dimension should be understood in a cosmic and extra-earthly sense, and if we are to trust the classics we can be sure to be on the safe side, quoting the well-known Homeric phrase (Iliad, 8.13-16) which places Tartarus "as much below Hades as heaven is from earth".

Bibliography:

- Emanuela Chiavarelli, Diana, Harlequin and the flying spirits (Bulzoni, Rome, 2007).

- George Dumezil, Stories of the Scythians (Rizzoli, Milan, 1980).

- Mircea Eliade, Zalmoxis in From Zalmoxis to Genghis Khan (Astrolabio-Ubaldini, Rome, 1983).

- Julius Evola, Revolt against the modern world (Mediterranee, Rome, 1969).

- Rene Guenon, The King of the World (Adelphi, Milan, 1977).

- Karoly Kerényi, Dionysus (Adelphi, Milan, 1992).

- Peter Kingsley, Mysteries and magic in ancient philosophy (Il Saggiatore, Milan, 2007).

- E. Lot Falck, The shaman's drum (Mondadori, Milan, 1989).

- Charles Malamoud, The solar twin (Adelphi, Milan, 2007).

- Plutarch, Isis and Osiris (Adelphi, Milan, 1985).

- Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, Hamlet's mill (Adelphi, Milan, 1983).

27 comments on “Divinity of the Underworld, the Afterlife and the Mysteries"