An exciting journey to discover the link between the carnival festivities, the flagship of Sardinian folklore, and the ancestral cults that marked its past

di Alberto Massaiu

Article originally published on author's blog on February 15, 2015. Since the report reported here incorporates topics already dealt with on our site, mention will be made of previous articles published where they can clarify some points of the discourse that otherwise could be obscure.

What I'm about to tell you in this article is the result of the suggestions derived from reading a book by Dolores Turks, a scholar of popular Mediterranean traditions. The fame of the archaic, fascinating and disturbing Sardinian masks reaches far more extensive shores than the national ones. Foreigners from all over the world go to Sardinia during the carnival period, or during the summer festivals or even in famous parades such as the Sardinian Cavalcade of Sassari, in May, a unique opportunity where you can find, concentrated in one place, the most famous masks, such as the famous ones mamuthones, the boes and merdùles.

Well, this article will delve into the darkness of oral tradition and custom. Little or nothing we will talk about comes from the historical tradition, at least in the academic sense where by history we mean what we can prove on texts, documents, finds. Together we will wander into the world of the most ancient folklore and a very ancient pagan religion. Our journey is based above all on memories of elderly people, on hypothetical reconstructions, on connections and juxtapositions with long-lost rites and traditions. Buckle up and get ready to immerse yourself in a world that is totally alien to us.

Let's start with some historiographical considerations (yes, they will be the only ones, I guarantee it) that will help us to better frame what we are going to see together. The origins of the Sardinian carnival date back to at least 3.000 years ago and over the centuries they have undergone a whole series of infiltrations, contaminations, revolutions and cultural superimpositions by the many peoples who came from overseas. The biggest blow, from an anthropological point of view, was struck following the affirmation of Christianity, which as its custom tried to overlap and incorporate the pagan tradition, "domesticating" the parts most in contrast with its principles and emptying gestures and rituals of the original sense.

[cf. Maculotti, From Pan to the Devil: the 'demonization' and the removal of ancient European cults]

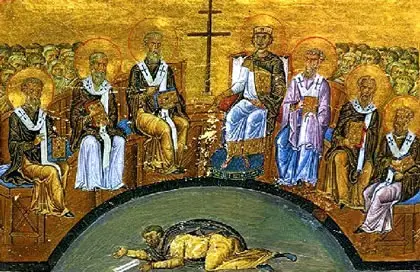

It was a long task, lasting generations and generations, but not impossible. This is because Christianity could make use of learned and wise men who wrote and annotated everything. They could easily transfer information, regulations and rules, to which they combined a vast, powerful, rich and centralized system of administration. From the first Councils of Nicaea (325 AD), of Ephesus (431 AD) and Chalcedon (451 AD), followed by the practice of the papal bulls of the Middle Ages, everything was codified, archived and studied. A much more solid and organized system than the oral traditions of classical and mystery Paganism.

The procedure was simple and relatively painless. The Bishop, who was staying in a large and populous city where proselytism was easier, began to inquire about the rural cults dedicated to Dionysus, Demeter, Diana and thousands of others, often linked to the cycles of nature and seasons, or of the waters or more fertility. At this point he was alone an operation of creativity first and then of propaganda. There was a local saint - better still a beautiful martyr -, a miracle connected with the cult that was practiced in the pagan sanctuary was attributed to him and he was associated with the local festival. Saints and saints then appeared who had performed miracles related to the rains in the Wells or in the Sacred Sources, or others who treated specific diseases where the pagans believed it was possible to obtain luck and health and still some capable of protecting the crops where Ceres and divinities were venerated in her affini and so on.

[cf. Maculotti, Imbolc, the triple goddess Brigit and the incubation of spring]

We also find all this in the same language. Do you know where the derogatory term pagan comes from? From the late Latin term pagus, or the one who lived in the countryside. The pagans were those who, living far from the cities, which were Christianized more quickly, continued to practice the ancient local and rural cults of their ancestors. For this reason Sardinia has preserved the remains of its ancient traditions for so long. Because, except on the coasts, it has never had a great urban development. Moreover, it was very difficult to deal with the peoples of the interior, perched on their rugged mountains and in the impenetrable woods, which remained almost entirely pagan until the ninth century, if not beyond.

Certainly on the island the work of superimposition with Christianity took place in a later period than in other areas of Europe and above all in a much more superficial way. It is for this reason that we can find much clearer and more precise references to the rites that were performed there thousands of years ago. The masks of the Sardinian Carnival change from area to area, from town to town, but they maintain a whole series of common traits, referring almost all of them (especially those of the interior) to a single origin. An ancient and probably violent cult, linked to the fertilization of the earth and the Dionysian sacrifice.

We also took a big risk. At the turn of the First World War, with many young Sardinians recalled and killed at the front (over 13.500 who died in the trenches of the Piave, the Isonzo and the Carso), with the uprooting of the new generations from their countries of origin there was a gap cultural, the real fatal blow to an oral tradition; many young people did not learn their traditions from the elders. The various carnivals were abandoned, falling into disuse. Industrialization, urbanization and an exasperated modernism (which at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries led to the "redevelopment" of historic centers, a euphemism with which the demolition of medieval buildings, towers, walls and even castles was justified to make room to new buildings with a more contemporary taste) did the rest. Fortunately, in recent decades, behind the push of a new generation of scholars, with a tourist and cultural interest in ancient traditions, an attempt has been made to reconstruct at least the external form of those ancient lost cults.

But let's take a closer look at some of these masks. We have, most famous of all, i mamuthones and issohadores of Mamoiada, the best known Sardinian Carnival. The former have masks of black wood, dyed with charcoal, with disturbing humanoid features. They wear sheepskin and heavy cowbells on their backs, which signal its arrival from afar, as once in war the enemies were terrified with the dull sound of horns and battle drums. THE mamuthones they march solemnly, performing the steps of a dance made up of rhythmic leaps, aimed at making as much noise as possible, trying to remember the sounds of a large approaching flock. - issohadores instead they are humans, also transfigured and dehumanized by cryptic white masks, dressed in red jackets and trousers of the same color as their masks. THE mamuthones try to escape from them issohadores who, armed with laces, occasionally capture one, which writhes and laments. Now everything has taken on a fun and folkloric touch, where the issohadores they are more concerned with "capturing" a young tourist who watches the show, but once upon a time this was a real ritual that had its roots in the agro-pastoral world and where, probably, i mamuthones captured represented symbolic victims (and perhaps in truly ancient times not only) of a sacrifice linked to the prosperity of herds and crops.

Ad Ottana instead we have a little less known figures, although they are very important in the Sardinian carnival tradition: il boe, shit , Filonzana. The Carnival of Ottana is perhaps the most famous after that of Mamoiada and has preserved some of the oldest references of the pagan tradition. THE boes they are, as you can imagine, the representation of oxen. They have large sheep or goat fleeces, a band of gigantic cowbells - which weighs 30-35 kg - and beautiful bovine masks with leaves carved on the cheeks and with a strange symbol on the forehead, in the shape of a star, whose meaning remains obscure. The mask is completed by the eyes, almond-shaped and always upwards, the pronounced muzzle and the high horns, traditionally 15-20 cm, straight or curved inwards.

I shit they are a different version of the issohadores. They wear the same skins as the boes, they have black velvet trousers and a handkerchief of the same color on the head. They bring humanoid masks as black as embers, deformed and grinning as if they were old shepherds bent by fatigue. On the shoulders they carry "Sa taschedda", a tanned brown leather bag, where supplies were once stored. They walk trudgingly holding on to a said stick "Su mazzuccu" and uttering strange and mournful laments.

I boes they are often yoked together and spurred on by merdùles, who play their human masters. THE boes they can kick, run wild, drop to the ground. Here the ancient pantomime takes place, where i merdùles they have to kneel down and calm the animal, stroking it on the muzzle and encouraging it so that it gets back on its feet and starts again in its hard work to till the soil in an archaic rite of fertilization of the earth. Particularly disturbing are the two figures who generally close the procession, the shit that brings with it "S'orriu", a cork cylinder covered with tanned leather that has a long cord inside that is rubbed by the hands, specially greased with grease, of the shit. This gesture produces a dull, low sound that serves to intimidate the boes, making them more meek and docile towards their masters.

If then i boes continue to rebel the last and most terrible character of the Ottanese Carnival, the Filonzana. This mask represents an old woman, dressed all in black like the Sardinian widows with skirt and shawl, small and humped, almost shrunken in herself. He wears a black handkerchief on his head and a mask made of wild pear wood, the sacred tree of a whole series of lunar and underworld deities such as Persephone, Zeus Katactonios and Kronos-Pluvius, widespread throughout the Mediterranean although with other names. also dyed black. The man (traditionally no Carnival mask can be interpreted by a woman) moves in an awkward and dangling way. In total silence, which stands out even more in contrast with the moans and moans of the other figures, he carries with him a spindle and large scissors. La Filonzana she is the one who weaves the thread of life, a cryptic, fearful and dark figure, which sends a shiver down his spine as he approaches someone to threaten to sever the thin thread of his existence.

In the archaic world this mask had a very powerful sacral value. She was the Parca of the Hellenic tradition, the mistress of destinies and fate. A figure who, if not respected and feared properly, could bring misfortune, curse, famine and death to the desecrators of the Rite. In an ancient agro-pastoral world as it was, and to a small extent still is, the Sardinian one, linked to the whim of the seasons and incomprehensible natural forces, superstition and the benevolence of the divinities played a fundamental role and Filonzana he was their herald in the world.

This also allows us to understand the level of religious syncretism, of contamination and translation of rituals from one culture to another in the Mediterranean. In Sardinia, as in the Italian Magna Graecia, the Eleusinian and Dionysian Mysteries were practiced, strongly anchored to nature, lunar cycles and seasons, earth and water. Many of these typically rural rites were linked in ancient times to animal sacrifices but also, most likely, human sacrifices. Certainly these sacrifices were violent and had their saving principle in their blood. Blood, which brings life with it, is the only thing capable of fertilizing the earth and requesting particular benevolence and favors from the gods.

Before being scandalized by an act of such barbarism for our modern and advanced civilization, let's put it in context with that world lost in the darkness of history. Life was much more precarious, death a constant constant. For a slight flu or childbirth, or for a trivial cut, you could leave your feathers. Agriculture and livestock allowed a very meager subsistence and only the nobles, the priestly castes, the warriors and perhaps the first merchants reached 40 years of age. The peasants died at 20-25 if it suited them and infant and female mortality was very high. We were used to death in a much more marked way than we are and, above all, this was experienced as a collective phenomenon. In the small villages the funeral of anyone was shared by the whole community and therefore even as a child, if one had been lucky enough to overcome the red zone of childhood, there were many transitions. To all this we add war, feuds and slavery, in a world where the concept of human right did not exist and maximum values were included in the "Laws of Hospitality" - dear to the Greeks, as Homer tells us, but also to the Sardinians, where they are still very much alive - and in the feet religious.

Let's look at the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hebrew, Greek, Etruscan, Latin, Celtic, Germanic myths. We have divinities, demigods, heroes and princes who kill treacherously, cut to pieces, rape, torture, even make fathers feast on their sons and daughters (do you remember the curse of the Atrides, the lineage of Agamemnon?), Practice incest, pedophilia, the murder of relatives, even zoophilia and necrophilia. If you take the time to read some Greek or Egyptian myths you will find yourself exploring a somewhat perverse horror movie by our standards. But even the Bible does not joke, starting from the Good Old Testament, with cities swept away, universal floods, murders and so on up to the final sacrifice, which was to put an end to all other sacrifices, of the same son of God, Jesus Christ ( did you know that an accusation that the Romans made to Christians, naturally not understanding the depth and meaning of that gesture, was precisely that of "deicide"?).

Many scholars of ancient religions will be able to explain to you that very often these myths had a meaning which, in their own way, served to educate people about what not to do. He did it hard and raw, with terrible examples, why the world in which we lived at the time was even more harsh and terrible than the myths themselves. We rightly have every right to be scandalized, although we too, between world wars, atomic weapons, exploitation of the third world, drugs and so on, are not in our turn first-haired virgin. All this reasoning I did to introduce, with my mind free from a whole series of "good" moral preconceptions that we raise to protect our psyche, the last part of this article, relating to most controversial and disturbing figures of the Carnival and what I believe was its darkest and most hidden meaning.

To introduce it we quickly see a whole series of masks which, with the natural and obvious peculiarities due to the differences in celebration from country to country, however, have a fairly clear reference to the scheme we have outlined for Mamoiada and Ottana. We have "Sos corriolos" by Neoneli, in the province of Oristano. Recently discovered thanks to documents from the XNUMXth century, he wears a cork headdress, on which deer or fallow deer horns are applied, is dressed in hedgehog skins and wears animal bones on his back instead of cowbells, which are shaken with rhythmic movements similar to those of the mamuthones or boes. Probably, but this is my personal opinion, this mask represented the closure of the cycle of agricultural work, that is hunting, which completed the triad made up of agriculture and livestock. His reference animals were clearly wild, not domestic or semi-domestic like oxen, sheep or goats or pigs and therefore recalled the time when a thick and numerous game lived in the forests of Sardinia. It must have had the same origin "Is cerbus" by Sinnai, in the province of Cagliari, also in memory of ancient hunting expeditions.

To close this section, the penultimate of the article, I would like to mention i turpos by Orotelli, totally dressed in dark cloaks and hoods, without masks but with a face dyed black with charcoal and wearing small bells over their shoulder. They too come along the lines of the tradition of Mamoiada and Ottana, as they represent a whole series of pantomimes from the pastoral and peasant world, with yokes for the beasts, small plows and snares to capture beasts and tourists.

Very good. Here we are now at the final and conclusive part of our "initiatory" journey in the exploration of an older cult of classical civilization. To do this we will use some of the darkest and most tragic masks of the Sardinian Carnival. Now you will know the "Mascaras Bruttas" darker. With the term ugly mascaras they indicated those masks that had too evident references to the pagan tradition and therefore were strongly opposed by the Church during its work of evangelization (moreover in this case it was an abortive attempt, as luckily, at least in the forms, these ceremonies were preserved until the dawn of the twentieth century), which separated them from "Mascaras Nettas", or from those considered more harmless and therefore admitted.

[cf. Maculotti, The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany]

Here are the "victims" of the Carnival: the S'Urzu by Samugheo, S'Orku foresu of Sestu, Don Conte of Ovodda and the most famous "Su Battileddu" by Lula. S'Urzu is the victim of mamutzones (slightly different from mamuthones of Mamoiada) of Samugheo. These, with heavy cowbells and an ancient rhythmic dance, chase theUrzu, dressed in black goat skin, wears a single cowbell hanging from his neck and is held in a lasso by S'Omadore, his shepherd. The mask worn byUrzu it is zoomorphic, often a real stuffed goat's head with large horns and the helper has a face completely darkened by coal and soot. S'Omadore and mamutzones they push and goad the poor victim for the whole procession which in the distant past probably ended in front of a sacrificial altar.

Same sad story also for S'Orku foresu, also tied up, pushed, beaten and prodded by mustayonis with rods of reeds and olive (perhaps in antiquity they were made of iron and pointed), his mamuthones ante litteram. He is also loaded with cowbells, has a mask with horns, black robes and all the rest. When he fell, dying in the scenic-dramatic fiction of pantomime, i mustayonis they shout loudly "S'Orku foresu pedditzoi!". But, in a gesture that meant the cyclical nature of life in a process of death and rebirth, it was enough to throw close to theOrku a little straw and water to see it magically reborn, as the earth had to do after winter.

Very similar in meaning but even more tragic in representation we have the Don Conte. This is the absolute protagonist of the representation of Ovodda's country, but he is not played by anyone. He is a puppet made up of black rags, with a deformed cork or papier mache mask. He is carried in procession on a cart pulled by a donkey and celebrated in the streets of the town as a sort of "King of Carnival". At dusk, however, he is symbolically executed, burned and the remains thrown from an escarpment on the outskirts of the town.. At this point the bystanders go to celebrate all together with a large common banquet until late at night. If we read beyond the lines of the folkloristic festival, it makes us shiver to think that once upon a time, perhaps, instead of that puppet there could have been a human being. He was probably a prisoner of war, a foreigner, a madman, a slave or a criminal, who acted as a real scapegoat for the sins of the community, in an ancient violent rite of purification.

[cf. Maculotti, Cosmic cycles and time regeneration: immolation rites of the 'King of the Old Year']

Last of all, but not least, we have il Battileddu. Tragic figure and impressive mask, it is the true representation both of the concept of scapegoat and of the orgiastic sacrifice of "Dionysian" imprint. Let's be clear, with “Dionysian” I don't mean that in Sardinia exactly the Greek-classical Dionysus was venerated. Dionysus was in fact a very ancient figure, probably a divinity of nature common to all Indo-European peoples, so much so that his cultic expansion (with different names, of course) ranges from Iran to France and Spain. Dionysus was a deity linked to fertility, nature, the cycle of life and the seasons. In his myth of him, even in the Greek world, he died violently and was constantly reborn, as nature did in winter and spring.

[cf. Maculotti, Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun']

As many of those who have done classical studies will know, the Dionysian cults were characterized by outbursts of violence and brutality out of the ordinary. The men and women who participated in it entered a state of mystical trance so strong that it made them seem more like beasts rather than men. If you remember the myth of Orpheus, he is killed and torn to pieces by a group of Bacchantes, priestesses of Dionysus. Here, the mask of the Battileddu his face is stained with blood, blackened with soot, and he wears two large goat horns. Her body is covered with sheep and mutton skins, under which an ox stomach filled with blood is placed and she carries cowbells.

"Su Battileddu" he is the sacrificial victim of the Carnival and black-faced masks move around him and attack him several times to the point of killing him. With pins and small knives they pierce the stomach of the victim, causing the animal's blood to escape which, with a dramatic ancestral meaning, will fertilize the earth. Here too, as with Don Conte, Battileddu dying he is made to parade on a chariot amidst the incitement of the crowd, but in the end he will rise again, as in the Dionysian myth. On the other hand in the Sardinian language the Carnival is said "Karrasegare" which in the most ancient meaning literally means "to cut" or "saw" the flesh, in perennial memory of the violence of certain very distant rituals.

We are just closing. I hope I haven't traumatized you too much with my story about Sardinian masks. My opinion is the result of a series of readings, arguments and connections, but it does not have written texts to support it (except a sermon of St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo in Africa, who in the XNUMXth century AD he complained of shameful movements, bestial songs and robes, deer or goat horns and pagan sacrifices in the province of Sardinia) or archaeological evidence, if not reconstructions made by scholars of folklore and oral traditions. We know for sure that Dionysus had numerous of his altars in the woods, in the fountains and in inaccessible places; we know that he often manifested himself in the form of goat or deer and that in Sardinia a divinity of that type was called Maimone, at least since the Nuragic era (mamuthon, mamutzone, mustayone) and was linked to virile strength and fecundity. I have drawn some conclusions that are fascinating to me, but I do not take the right to say that these are the revealed truth.

In any case, I wish you all to come to Sardinia and witness these echoes of distant times in the festivals and fairs held in this period in Bosa, Mamoiada, Samugheo, Ottana and many other inland villages. If, on the other hand, you want a quick smattering all in one day, take advantage of the Ride of Sassari, in May, where you can admire not only the folklore masks, but also the ancient traditional costumes of my land. They are a show not to be missed for any reason in the world, also because their destiny, like all oral and customary traditions, are heavily threatened by the carelessness and superficiality of our modern and consumerist society.

6 comments on “The distant origins of the Sardinian Carnival"