The 'spiritualization' of animals and their respective archetypal functions in the holistic view of the Native Americans of the far north

di FRANCESCO SPAIN

Reworking of the article originally appeared in FERRI Laura - GIANNELLI Luciano (edited by), Visions and interpretations of the Arctic and Subarctic North, Quaderni del CISAI, Siena 2006, and later included in the volume SPAIN Francesco, In the footsteps of tradition. American Indians and us, Imprimitur, Padova 2008. Originally published on the profile I Academia.e of the author.

"Nobody cohe knows the ways of the wind and the caribou. "(Chipewayan proverb)

The purpose of this article is to introduce the vision of animality (and of the relationship between humanity / animality) at the native cultures of subarctic America. The aboriginal cultural traditions of this environment are in fact an interesting example of cosmovision strongly centered on the animal sphere and its own symbologies. Rèmi Mathieu, with a particularly happy expression, defined the bear in Asian representations as a piège à symbole, a symbol trap (MATHIEU R. 1984: 12). The bear is not unique in this genus and subarctic America shows not only the poignancy of this order of significations but also their relative untranslatability with respect to ours categories of thought. With Aesop's fables, as Gregory Bateson rightly observed, Western thought has taken its own particular path, which has led us to Disneyland. In shamanic traditions it is different: animals are not simply heuristic creatures, they are architects and founders of meaning.

Three anthropologies

We can identify three different anthropological approaches to this theme. Levi-Strauss, no The thought wild (LÉVI-STRAUSS C. 1964 [1962]), deepened in an original and innovative way the analysis of relationship between animality and humanity, focusing on the mental and symbolic level. The conclusion - became a classic - it was that animals, for humans are also "good to think about": That they are porcupines, horses or birds, their characteristics are suitable for elaborating conceptual systems e classifiers. According to Lévi-Strauss, animals offer themselves to human thought as if they were philosophical categories. In the depths of the Amazonian forests as in the Australian deserts, thought abstract is universally exercised.

More prosaically, over twenty years after the work of Lévi-Strauss, Marvin Harris wrote his "Good to eat" good to eat (HARRIS M. 1990 [1985]). Although it is a fun and informative one book on food habits, the reference / comparison with the position of Lévi-Strauss is evident. The collective stomach is prioritized, according to Harris, to the collective mentality. The report between humanity and animality, conceived mainly on the edible side, is resolved in terms of a cost / benefit ratio. A form of scientific reductionism, which leaves it as a prerequisite implicit is the ability of the Western anthropologist to rationally interpret and explain them practices of others.

The reconsideration of Bateson on totemism - interpretable as a pedagogical, sapiential or religious device, which postulates the correspondence between the human and animal spheres, with particular reference to family (BATESON G. 1984: 189-90) - is extremely important for the purposes of our discourse. If of it is usually regarded as typically human creation of meanings - the "production of sense” - this perspective in totemism is reversed, because are the animals, in the totemic myths, a create the world for man too. It is they, as Ingold points out, who define the "design" of human society and its order, they are responsible for it. On the contrary, in ours current conception, it is man who must administer the animals, exploiting them as a resource, taking charge of theirs survival, or the responsibility for their extinction (I.NGOLD T. ed. 1988:12).

Totemism and shamanism

[cf. MACULOTTI, The Sacred Circle of the Cosmos in the holistic-biocentric vision of Native Americans e The oral tradition of the "Big Stories" as the foundation of the Native Peoples Law of Canada]

It is not immediate to understand this ideology, if we think about the harsh environmental conditions of subarctic. The hunter who brings large prey to the village - be it a moose, a bear or a caribou - distributes it equally in the community. He brings plenty of food for everyone, he organizes one party. However, luck in hunting is alternating, the movements of the animals are unpredictable. In a delicately balanced ecosystem, such as that of the subarctic, famine is always possible. That's enough little because a herd of caribou make themselves invisible, unobtainable in the vastness of the tundra. Yet it is not these difficult conditions that discriminate against a specific cultural trend: spiritualize the animals.

Eight animals will help us understand the thinking of the natives of the subarctic: the caribou, the salmon, the beaver, the otter, the bear, the toad, the wolf and the crow. All animals strongly spiritualized: Ma they are certainly not the only ones! Other series could be considered equally, for example: elk, Lynx, wolverine, porcupine, woodpecker, muskrat, swan, trout. Caribou and salmon are essential for nutrition and life itself in the subarctic. The bear is "good to eat", but not essential. The crow and the toad are not edible, or are considered "not good", like the wolf, the otter and the beaver. Although, in times of famine, anything can go.

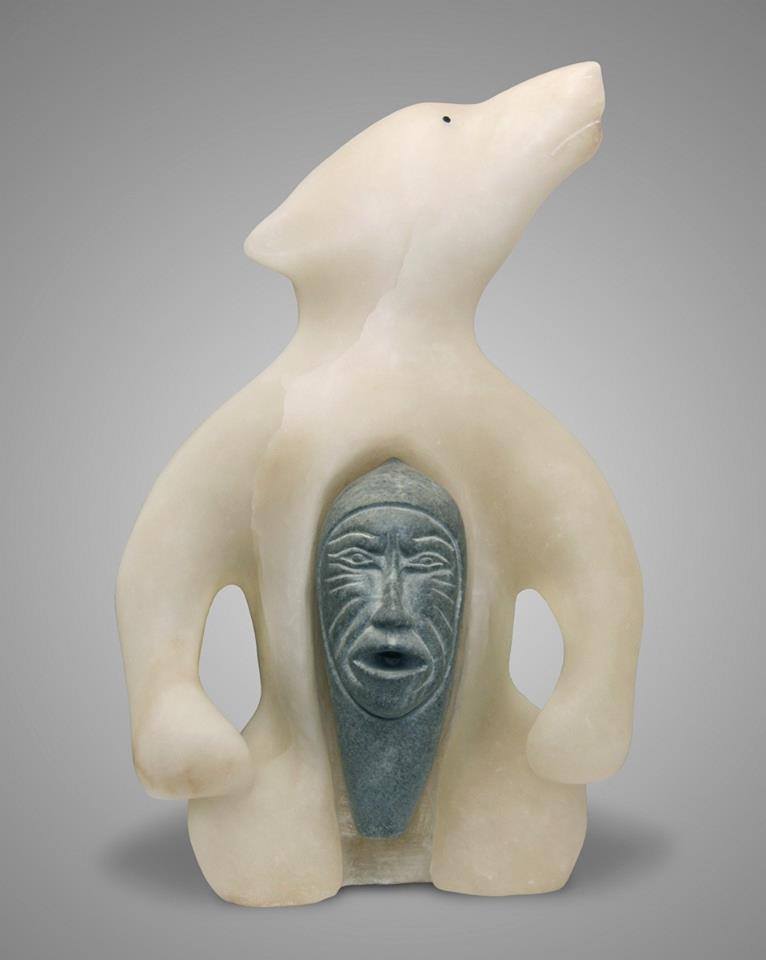

Napatchie Ashoona (Inuit), "Shaman transforming into a caribou".

Caribou

Moving west of Hudson Bay, in the athapaska area, we find other mythical-ritual complexes related to the caribou. The myth of the Lord of the Caribou (and, more generally, of the Lords of Game) is widespread throughout the subarctic area. The Chipewayan version was collected by Kaj Birket-Smith in the XNUMXs. The the protagonist is the son of the union between a woman and a male caribou, so he is half a being human and half caribou. He lives part of his life among humans, but they mistreat him. He goes therefore to live definitively among the caribou. However, he will continue to maintain relationships with humans. If called with the shamanic rite, he will send the caribou as a gift to the hunters (B.IRKET-SMITHI K. 1930).

Tanner's research among the Innu of Quebec and Labrador revealed the traces of an ancient and important female cult linked to the caribou. The rite was performed during a particular winter night, in which a skin of this animal was prepared and decorated with vegetable tints, and then exposed - at the entrance of the tent - at the first ray of sunshine of dawn, like offering to the spirit of Donna Caribù. The leather was then immediately rewound and carefully stored in a secret place (TANNER A. 1984: 91 and s.).

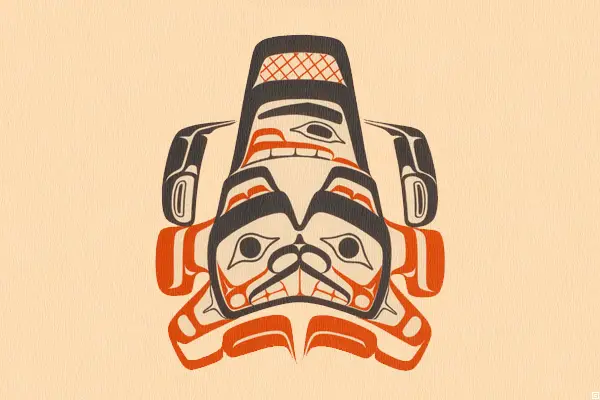

Salmon

A curiosity has arisen on the spirituality of the salmon and the sacredness of its breeding grounds - and perhaps only - form of cultural coincidence. So much so that these places, be they along the rivers which flow from the Arctic into the Pacific or Atlantic, are now officially called "Sanctuaries". Salmon represented a fundamental food resource for native peoples Canadians, both on the eastern side, along the tributaries of the San Lorenzo channel, and on the side to the west, along the Fraser River, salmon have always satiated the people of the Lower Cordillera alaskana. The populations of the coast of North West, just below the limit of the subarctic, you are sedentarized - elaborating complex and stratified societies - precisely in correspondence with the places of rising salmon, which offered a constant and abundant food source.

American salmon did not eat, like their European relatives of Celtic myths and gods Welsh legends, the nut of knowledge. However, forms of ceremonialism for their remains they are observed among many native peoples of the Canadian subarctic. The Salmon Prayer of the Kwakiutl, collected by Franz Boas in the XNUMXs, bursts with sincerity enthusiasm, together with a deep feeling of respect for this animal. Example of a hunting ideology that above all exalts the gift that animals, with their nourishment, bring to humans. An inseparable gift from their own blessing (BOAS F. 1930: 206-207; C.SHADOW E. ed. 2001):

“We have come to meet you alive, Swimmer. Don't think badly of what I did to you, man Swimmer, because that's why you came, for me to catch you with the spear, for me to eat you, Being SopranNatural, you, Long Life Giver, you Swimmer. Now protect us, (me) and my wife, so that we can stay healthy, so that they don't exist difficulties for us in getting what we want from you, Woman-Who-Produces-Riches. Now call, after you, your father and your mother and uncles and aunts and older brothers and sisters, that they too come to me, you Swimmers, you Satisfiers. "

Beaver

The missing information on beaver ceremonialism in Native Canadian traditions is from very significant in themselves: the beaver has seriously risked extinction, due to a hunt intensive and targeted, implemented according to a European model and benefiting from an incipient process ofglobalization. European fashion, in the 16th and 17th centuries, involved beaver fur headdresses,which replaced the old felt hats. This was one of the main reasons that prompted i merchants from Nouvelle France to send their own voyageurs e coureurs de bois to search of fine furs. The meeting and peaceful collaboration between French and fur hunters Algonquian natives made the history of Canadian civilization (TRIGGERS B. 1985; S.PAY F. 2002). The the price to pay, however, was expensive. Diseases brought by Europeans - especially smallpox - to which the natives were not immunized, they spread along waterways, brought by animals, and they exterminated entire populations.

The imposition of a hunting system based on accumulation and on profit irremediably altered natural ecosystems and communal relations between native groups. Beaver fur became, in the 18th century, a kind of local currency. With the establishment of the English Hudson's Bay Company and then the American rival North West Company la hunting beavers and other fur animals assumed industrial proportions. According to sources historical, in the early V yearsbodies of the nineteenth century along the rivers Churchill and Nelson the beavers were extinct and the other fur animals that have almost disappeared (MART C. 1978; LEACOCK E. 1954).

Previously, when hunting was still part of an integrated system with the environment, the beaver had a particular role. From its glands a particular oil was secreted, which came sprinkled on traps to ward off human odor and attract animals. With the incisors of beaver they made scrapers for the tanning of the skins. From the few and incomplete information, however, it appears that even the beaver, before the 17th century, it was a strongly animal spiritualized.

Among the artifacts of the Blackduck culture - located in the Great Lakes and Southern Manitoba region, in one period, the Terminal Woodland, roughly corresponding to our Middle Ages - there are stone amulets in the shape of a beaver. The ancient ceremonialism for the beaver may have had a similar intensity to that for the bear. If it goes back with the sources, we find news of beaver skulls hanging from the trees, or of rituals made on his fur. In a founding myth of the Trembling Tent ceremony, among the Eastern Cree, we find a curious passage relating to a food transgression carried out by protagonist, who had fed beaver meat to his children, thus losing his own luck on the hunt (FLANNEY R. - CHAMBERS ME 1985: 12-13).

The beaver's industriousness, social life and intelligence impressed the minds of the natives like those of Europeans. The beaver lives its environment, building itself shelters that resemble small villages. The humanizing metaphor produced by this animal is very strong. According to a myth anishinabe, beavers are directly descended from an ancient Indian family (BROWN J. -BRIGHTMAN R. 1988: 121). According to the Missinippi Cree, the beavers were considered "wiser" of humans.. In this regard, a Nez Percé myth, quoted by Lévi Strauss (LÉVI STRAUSS C. 1993: 109-110), in which a beaver-trickster, like a little Prometheus, steals the The fire:

“At the time when animals and trees talked, only Conifers possessed fire. During a particularly harsh winter, all living beings risked dying of cold. While the Pines were gathered around a beautiful fire, Beaver stole an ember and distributed it to the other trees. From that time it was possible to make a fire by rubbing two pieces of wood against each other. "

The American Beaver and his Works is the title of a work published in the nineteenth century by the famous anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan, one of the first field researchers in the Canadian area (MORGAN LH [1868] 1970). Also Alfred Irwing Hallowell, in his work dedicated to ceremonialism of the bear, compared the beaver's intelligence level to that of the grizzly, among the highest on the scale animal (H.ALLOWELL FW 1926: 149). A Tale of the Cannibal Spirit Windigo, which I collected in a nearby anishinabe reserve from Lake Superior, significantly summarizes the theme of the beaver's humanity with that of the human madness:

“There was once a hunter who was particularly good at catching beavers. He was able to hunt in large quantity. In reality he did nothing in his life other than killing beavers, so he spent all his life time. He spoke only of beavers. One day she entered his village and saw no human beings, but beavers. He saw a family of beavers in a beaver village, and began killing and eating them. It was his family che was killing and devouring. He had been possessed by the Windigo. "

[cf. MACULOTTI, Psychosis in the shamanic vision of the Algonquians: The Windigo and MOLLAR, Jack Fiddler, Wendigo's last hunter]

Bear

On the human aspects of the bear, on its intelligence and on its very particular character, there is - in Native traditions of the Canadian subarctic as in the whole circumboreal area - an overabundance of myths, legends, symbols, the most varied representations, songs, proverbs, riddles. The grizzly bear is said to be able to devise tricks to confuse hunters, retracing retracting his own footsteps and then waiting for them at the passage hidden in a bush. It looks like the bear polar is aware that his black nose stands out in the distance in the white expanses of the pak, and therefore while hunting the seals he has the accuracy of covering it with a paw.

The ability to keep a along the upright position makes the bear particularly akin to humans, even on a symbolic level. Looking inside the bears' lairs, bedding can be seen carefully prepared, separated for the male and the female. It is said that the mother bear, when feeds her puppies, emits a low rumbling sound that resembles a lullaby. So much so that some, among the thousand derivations from the Indo-European root bher, also include "berry"(SHEPARD P. - SAUNDERS B. 1985). Il mythical theme of the mother bear it is undoubtedly the most important and fundamental.

The research I have performed on the symbolism of the bear - in particular in subarctic America and in general throughout the circumboreal area - they took me to consider the centrality of the female elements in this mythical-ritual complex (S.PAY F. 1998: 217-246). Many scholars of the history of religions, not without foundation, have allowed themselves to be tempted to see in circumboreal bear cult one of the oldest forms of religiosity developed by Homo Sapiens. On the bear worship among Neanderthals and on the existence of sanctuaries for the bones there is a long time debated. The devotional statuettes of the Vin cultureča, found in ex-Yugoslavia, date back to at least 7000 years ago (G.FUNNEL M. 1990:116).

Hang the bear's skull from trees, paint it red ocher, ritually treat the fur, le paws, claws, teeth or internal organs, organize collective parties during which the meat of the bear is ritually consumed, or shamanic initiation rites centered on bear symbols, are all cultural traits widespread among the Nordic peoples, from the Lapps of Scandinavia to the Iroquois (HALLOWELL AI 1926).

Along the circumboreal subarctic area, at least four distinct cult “centers” can be identified of the bear: one in western Siberia, in the land of the Mansi-Shanti. A second among the peoples of the Siberian Far East and the Ainu of the island of Hokkaido. One third in the Yukon area e of the North West Coast, between the Tlingit or Tsimsyan. A quarter in the Canadian Shield area e in particular at the Anishinabe of Lake Superior.

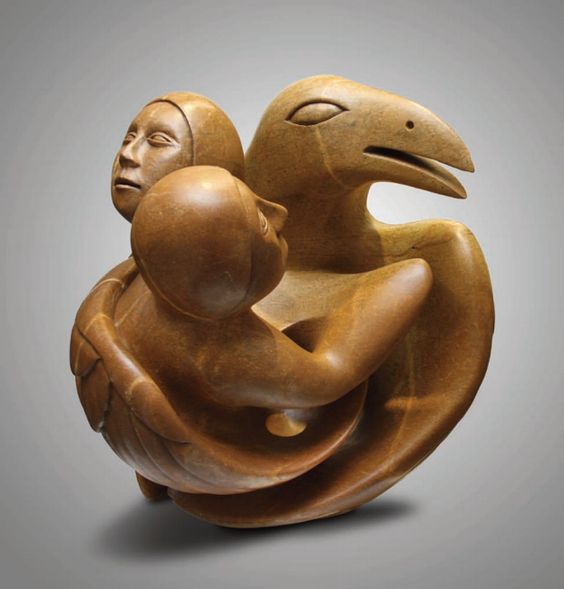

On the mythical level, the theme of children kidnapped and housed in a bear's den - considerable as myth of the foundation of the bear cult - it unites the whole circumboreal area into a single complex of variants that intertwine and overlap. In the Yukon area is a girl who goes in marries a bear, and the themes of femininity and motherhood are predominant. In the variant Tsimsyan, the protagonist is welcomed to the bear village and prepared for marriage through an evidently initiatory ceremony, in which she is made to wear a bear fur coat (MCCLELLAN C. 1973 - BARBEAU M. 1945).

In the eastern Canadian versions, the bear's shamanic abilities are very much in evidence. The bear spawn abundant food in the lair, or use her powers to magically clear the lair human memory of the boy and deflect the attempts made by his father to recover it. He teaches the little boy elaborate ritual instructions, or leave him one of his paws as an amulet. Returned to his village, the protagonist will become a great hunter, having inherited the power from the animal shamanic (BARRIAULT 1972; B.ARNOUW 1977; T.ANNER 1979; sCOOKING c. 1993). In the initiation ceremonies of the Medicine Hut (Midwiwin), Orso is among the main ones ministering spirits. The ritual affinities between the circumboreal bear cult and ceremonies Midwiwin of the Lake Superiore undoubtedly welds the complex of hunting rites with the shamanic one (SPAY F. 1998). From the Siberian taiga to woodlands Canadians, bear shamans and shaman bears yes they continually exchange parts.

Otter

Alongside the bear, to bring the shamanic gift of Life into tradition Midwiwinappears Otter. With agility and elegance, the otter moves indifferently under water and on land. Integrate therefore two worlds - terrestrial and aquatic - usually considered in opposition. This agile and darting metaphor brings us a new element: the game. The otter is a very playful animal, the his bark is reminiscent of a cheerful laugh. The shamans have chosen it as a symbol of the joy of living, of playfulness, the hope of happiness and the continuity of life in the underworld (H.ARRISON J.1989: 90). The medicine bags obtained with an entire otter fur, finely decorated and equipped with rattles, they constitute the main initiatory kit Midwiwin.

A creation myth

When the first ray of light appeared - tell the Cree - Mother Earth gave birth to the first spirits of world. The first child was Biney-sih, the Thunder Bird. He appears as a thunderbolt in his eternal struggle with the Serpent of the Waters. The second son was Oma-ka-ki, the toad. Help with her powers other animals are shamanic. The third son was the Supernatural Man - the trickster - Wi-sa-key-jak, with the power to transform into anything. The fourth son was Ma-hi-gan, the wolf, companion of the trickster.

Wolves are gregarious, but also solitary, just like humans. Several myths underline this relationship of brotherhood. For the Anishinabe, once men and wolves they lived together, then they parted: in the middle remained the dog. The wolf, like man, is a hunter. THE Chipewayan saw their way of life - caribou hunters - reflected in that of wolves. The wolf raises rebirth theories: wolves reborn humans and humans reborn wolves. The return of the wolves to the Canadian forests was portrayed, by an Anishinabe spiritual leader, as a sign of the recent resurgence of Native American communities.

Corvo

The crow, Dotson ', is the main animal to which the Koyukon of Alaska turn their attention prayers. Like the eagle and many other birds, the raven is a shamanic helper, and above all messenger. In the Alaskan area - and on both sides of the Bering Strait - Corvo is the Trickster. Hero culture that creates, recreates and transforms the world. But also the spirit of contradiction, “clown omnipotent, benevolent swindler, fool, divinity " (NELSON R. 1983: 17). In the Koyukon myth of the Theft of the Sun, Corvo turns into a pine needle, gets swallowed by a woman who gives birth to him in the form of a man. Big enough to play, she goes and unrolls the blanket in which the sun had been hidden, and thus the world could have light.

In conclusion, the theme of metamorphosis and perceptual alteration - caribou seen as women, bears seen as spouses and shamans, relatives seen as beavers - is certainly central to the representations of these peoples. Metamorphosis that is combined with the shamanic vision: the main one spiritual path of the peoples of the subarctic.

Mythical time - the time when animals were humans and humans animals, when animals they spoke to humans and humans to animals - it is a living time, flowing below or around at the present time. It is considered by native traditionalists to be more real than real time. It is the time current, the daily and secularized time to be, in their opinion, the result of a distortion perceptive. The mythical time, for the subarctic cultures, represents the main reference axiomatic: moral and values. The stories told. Ideas for a continuous redefinition of the place of man in nature?

Bibliography of the works cited:

- BARBEAU Marius, 1945, Bear Mother, "Journal of American Folklore," 59.

- BARNOUW Victor, 1977, Wisconsin Chippewa Myths & Tales and their Relation to Chippewa Life, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

- BARRIAULT Yvette, 1972, Mythes and rites chez les indien Montagnais, The Société Historique de laCôte Nord, Quebec.

- BATESON Gregory, 1984 [1979], Mind and nature. A necessary unitia, Adelphi, Milan [ed. orig. Mind and Nature. A Necessary Unity].

- BIRKET-SMITHI Kaj, 1930, Contributions to Chipewyan Ethnology. Report of the Fifth Thule 1921 Expedition-24, vol. 6 (3), Copenhagen.

- BOAS Franz, 1930, The Religion of the Kwakiutl Indians, Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, Vol.

- BRIGHTMAN Robert, 1993, Grateful Prey. Rock Cree Human-Animal Relationship, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- BRIGHTMAN Robert A. - BROWN Jennifer, 1988, The Order of the Dreamed. George Nelson the Hon Cree and Northern Ojibwa Religion and Myth, 1823, University of Manitoba Press, Winnipeg.

- CSHADOW Henry (ed.), 2001, Texts religious of North American Indians, UTET, Turin.

- FLANNEY Regina - CHAMBERS Mary Elizabeth, 1985, Each Man has his Own Friend: the Role of Dream Visitors in Traditional East Cree Belief and Practice, “Arctic Anthropology”, 22 (1), pp. 1-22.

- GFUNNEL Mary, 1990, The language of deto. Myth and cult of the mother goddess in Neolithic Europe, Longanesi, Milan.

- HALLOWELL Alfred Irwing, 1926, Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern HemisphereAmerican Anthropologist (ns), n. 28, January-March.

- HARRIS Marvin, 1990, Good to eat, Einaudi, Turin [ed. orig. Good to eat. riddles of food and culture, Simon and Shuster, New York].

- HARRISON Julia D., 1989, He heard something laugh: Otter Imaginery in the Midewiwin, in: W. Penney (ed.), Great Lakes Indian Art, Wayne State University Press and the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, p. 83-92.

- HELM June (ed.), 1981, Handbook of North American Indians, vol.6, subarctic, Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

- INGOLD Tim (ed.), 1988, What is an Animal?, Unwin Hyman, London.

- LEACOCK Eleanor, 1954, The Montagnais “Hunting Territory” and the Fur TradeAmerican Anthropological Association, Memoir No. 78.

- LÉVI-STRAUSS Claude, 1993 [1991], History of Lynx, Einaudi, Turin [History of Lynx, Paris].

- LÉVI-STRAUSS Claude, 1964 [1962], Wild thinking, Il Saggiatore, Milan. [The penséewild, Paris].

- MART Calvin, 1978, Keepers of the Game: Indian - Animal Relationship and the Fur Trade, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- MATHIEU Rémi, 1984, The patte de l'ours, "L'Homme", XXIV (1), pp. 5-41.

- MCCLELLAN Catherine, 1973, The Girl Who Married the Bear: a Masterpiece of Indian Oral Tradition, National Museum of Man Publications in Ethnology, no. 2, Ottawa, pp. 1-58.

- MOORE Omar Khayyam, 1969, "Divination: a New Perspective", in: vIN THE MONTH (and.), Environment and Cultural Behavior, The Natural history Press, pp. 121-129.

- MORGAN Lewis Henry 1970 [1868], The American Beaver and his Works, New York.

- NELSON Richard K., 1983, Make Prayers to the Raven: a Koyukon View of the Northern Forest, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- PRESTON Richard, 1975, Cree Narrative: Expressing the Personal Meanings of Events, Canadian Ethnology Service no. 30, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa.

- SCOOKING Colin, 1993, Bear Symbolism and Ecological Knowledge in James Bay Cree Hunting, “Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Hunting and Gathering Society ", vol. 2, Moscow, pp. 617-626.

- SHEPARD Paul - SDIFFERENT Barry, 1985, The Sacred Paw. The Bear in Nature, Myth and Literature, Viking Penguin, New York.

- SPEK Frank Goldsmith, 1935, Naskapi. The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- SPAY Francis, 1998, The wild host. Visionary experiences and bear symbols in Native American and circumboreal traditions, Il Bookmark, Turin.

- SPAY Francis, 2002, The sweet misunderstanding. French Indians and voyageurs in Canada Seventeenth century, “Tepee”, year VI, n. 1, pp. 30-35.

- SPAY Francesco - LANOUE Guy (eds.), 2000, The strength in the parole. Narrative paths of Indigenous canadhered by Jacques Cartier to today, "Journal of Canadian Studies", vol. monographic, suppl. at no. 13.

- TANNER Adrian, 1979, Bringing Home Animals. Religious Ideology and Mode of Production of Cree Hu Mistassinsinters, St. Martin Press, New York.

- TANNER Adrian, 1984, Notes on the Ceremonial Hide, “Papers of the 15th Algonquian Conference ”, W. Cowan (ed.), Carleton University, Ottawa, pp. 91-105.

- TRIGGERS Bruce, 1985, Natives and Newcomers: Canada 'Heroic Age' ReconsideREDMcGill University Press, Kingston and Montreal.

3 comments on “Spiritual Animals: Native Traditions of Subarctic Canada"