The chosen land of a heroic and warrior elite who lived pervaded by the dimension of the Sacred, Sardinia can rightly be counted among the most important spiritual centers of antiquity: the aim of this study is to reconstruct through the lenses of history, of myth and tradition the development of the ancestral Sardinian ethnos and its culture

di Daniel Perra

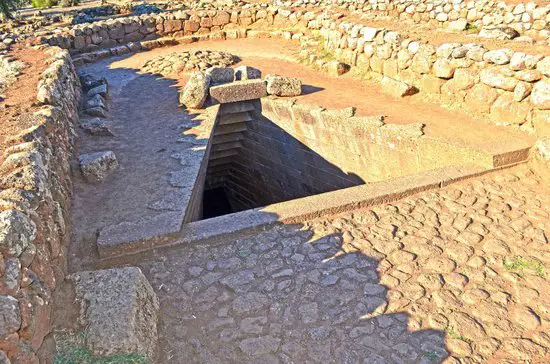

image: sacred well of the nuragic sanctuary of Santa Cristina

Origin and myth

An ancient Indonesian myth tells us that “in the beginning, when the sky was very close to the earth, God offered his gifts to the primordial couple by hanging them on the end of a rope. One day he sent a stone to the two primeval ancestors, but they, surprised and indignant, refused it. After some time, God again let the rope lower; this time he hung a banana from it, which was immediately accepted. Then the ancestors heard the voice of the creator: since you have chosen the banana, your life will be like the life of this fruit. If you had chosen the stone, your life would have been like the existence of the stone, immutable and immortal " [1].

Although far in the spatial dimension, this very ancient myth can be useful for understanding the value of western megalithic constructions. The human condition, in fact, lives in a state of perennial nostalgia for that instant in which man shared God's eternal time. And megalithism is intrinsically linked to the idea of the eternal survival of the soul after earthly death. Man hopes his name will survive and be remembered through stone. The stone guarantees the perenniality of the soul. And a stone substitute is a body built for eternity through which to recognize the figure of the ancestor, the hero and the divine himself.

The stone miracles of Sardinia, especially as regards the solar funerary monumentality, do not differ in profound meaning from the rest of the megalithic constructions that developed both in Western Europe and along the Heracleus arch of the Mediterranean Sea. Eternating memory, and with it life is also the goal of nuragic megalithism. Gods and dead need an eternity that only stone can confer.

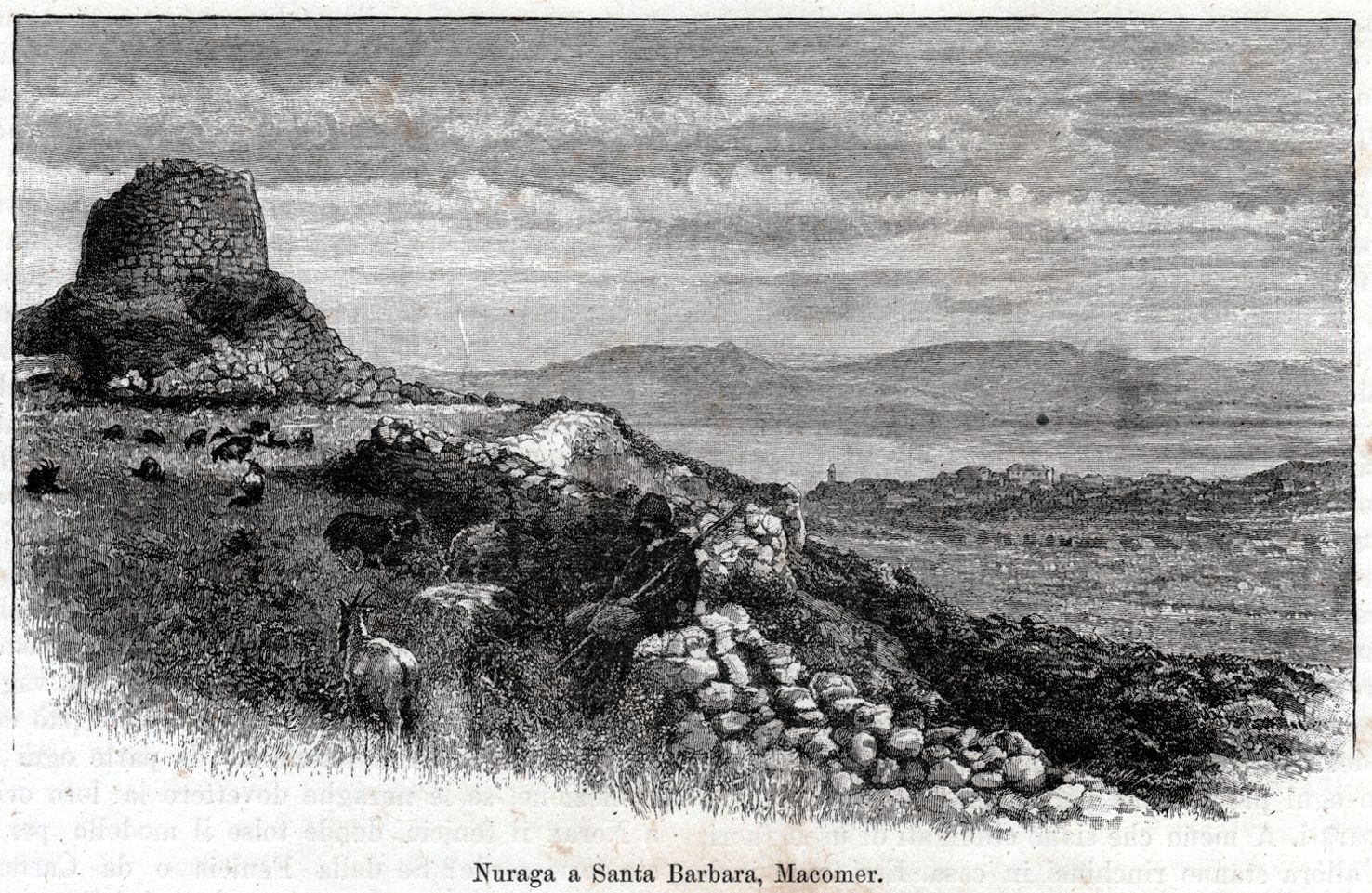

Il nuraghe (whose name derives from the Nuorese dialect word "nurra", hollow tower or pile of stones arranged on rows), the work of a mysterious Mediterranean lineage, pre-Indo-European and of Western origin, in its megalithic monumental essence based on an architectural science primordial, it has numerous iconographic links with other Mediterranean and Atlantic-European buildings. The nuraghe of Peppe Gallu-Uri, for example, is extraordinarily similar to talayot minorcan of Fontedrones de Baix-Mercadal. However, the Sardinian civilization was able to bring with it evident elements of originality that made it unique in its kind and fueled myths and legends about its origins.

The French scholar Louis Charles François Petit-Radel (1756-1836), inextricably linked to a romantic vision of archeology, struck by the cyclopean essence of the polygonal Nuragic walls and of central Italy, in the wake of Strabo and Pausanias, attributed their construction to the mysterious people of Pelasgians. With the term Pelasgos the ancient Greek historians identified all the inhabitants of the lands around the Aegean in the pre-Hellenic era to whom, among other things, a leading role was attributed in the process of populating southern Italy. These in the Iliad appear as allies of the Trojans, while Herodotus attributes to them the origin of the gods Tyrrenhoi: the name with which the Greeks called the Etruscans. Fled from Asia Minor due to a famine, the Lydians from the ancient city of Sardi, led by Tirreno, son of King Ati, from whom they took their name, moved to Italy. In fact, the Etruscan lucumoni were called "Sardinians" for this reason and, according to what Tacitus affirmed, the Lydians, for many centuries, continued to consider themselves brothers of the Etruscans.

However, the Greeks, with the term Tyrrhenians (builders or inhabitants of towers), did not refer to a strictly unitary people but to several peoples scattered along the northern arc of the Mediterranean [2]. Strabo, for example, defined the Iolai (or Iliesi or Iliensi - denominations that made scholars fantasize about a possible origin of the Sardinian civilization from Ilio / Troia), one of the nuragic populations of Sardinia, like Tirreni on a par with the Etruscans, and the Sardinians themselves as a population devoted to piracy . In this regard, in the Homeric hymn to Dionysus it is said: "And soon, in the solid ship, Tyrrhenian pirates appeared swiftly, on the gloomy sea:».

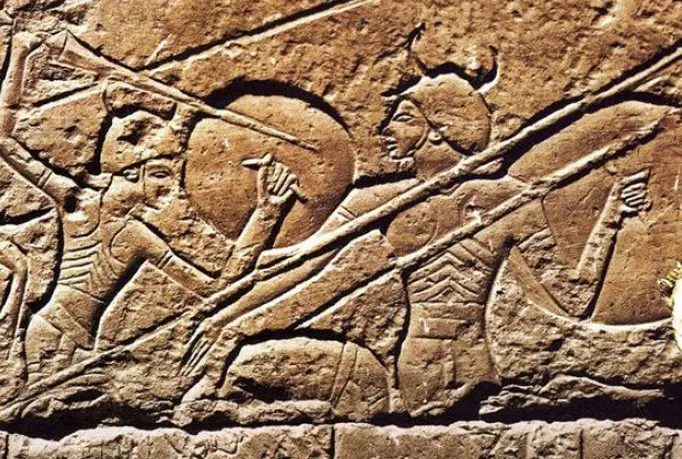

There is no doubt that there were fairly strong ethnic relations between Sardinians and Etruscans. And it is also not to be excluded that Etruscan populations passed to their historical site directly from Sardinia. Precisely the pirate, warlike and proud character makes it easy to assimilate the ancient nuragic peoples with another "People of the Sea"I Sherdana (or Shardana). It was Giovanni Spanu, father of Sardinian archeology, to evoke them first in the nineteenth century on the basis of the evident similarity between their armor with the bronze figurines typical of Nuragic art.

The Sherdana are mentioned several times in monuments and Egyptian written documents (reliefs of the temples of Abu Simbel-Karnak, Medinet Abu and the Wilbour papyrus). Described as a brave people and particularly trained in the craft of arms, they fight in various battles against the army of the Pharaohs and in particular alongside the Hittites in the battle of Kadesh on the Orontes of Syria in 1285 BC; alongside the Libi of Marmajon in the battle of Paarishep; and finally with the Tamhenu and the Maschavasha defeated by Ramesses III between 1181 and 1151 BC. guard body of the Pharaoh himself. Mansion described in the Wilbour papyrus and for which they received important landholdings in exchange.

The archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, finding the impossibility of recognizing a precise ethnic identity in the people who through a "western ebb" populated Sardinia between the recent Neolithic and the Chalcolithic, believed that there were insufficient data to confirm the hypothesis that the Nuragic Sardinians could be identified with a branch of the peoples of the "Great Green". To this we must add that about nine hundred years later separate the Sardinian culture of Monte Claro, through which proto-nuragic and nuragic building structures develop, from the date of 1370 corresponding to the most ancient citation of the Sherdana in the letters of Tel el-Amarna. However, the problem remains of explaining the radical detachment that is observed in the whole of the patrimony of inventions, activities and material life that is observed between the two historical periods mentioned above and therefore between the pre-Nuragic and Nuragic periods. So Lilliu himself admitted [3]:

"The hypothesis that at the end of the second millennium BC a combative people lived in Sardinia, which, with other peoples of the Mediterranean league, waging war on Egypt, reached the Nilotic delta or the Libyan-Egyptian border from the middle of the sea with their own flotillas , if it is not to be accepted uncritically, it cannot be completely discarded. The centuries in which the events of the Sherdana and the Confederates who want to expand to counter the hegemony of the Pharaonic power take place, are those in which the Nuragic communities, guided by their principles, reach the maximum splendor in architecture and develop a consistent and organized civil living »

Therefore, even Giovanni Lilliu, very unwilling to formulate hypotheses that did not go beyond the mere empirical observation of the facts, admitted that hypothesizing the arrival in Sardinia of daring human groups from the outside who gave life to the nuragic culture was not at all other than of historical logic. And in this regard he pointed out how the movements and displacements of entire groups of peoples had characterized Europe and the Mediterranean during the metal age.

Even the Australian scholar True Gordon Childe in his full-bodied work The Bronze Age it supported the identification between the nuragic peoples and the Sherdana [4]:

«In the nuragic sanctuaries and in the closets we find an extraordinary variety of votive statuettes and bronze models. Figures of warriors, crude and barbaric in their execution but full of life, are particularly common. The warrior was armed with a dagger and with a bow and arrow or with a sword, covered by a helmet with two horns and a circular shield. The clothing and equipment leave no doubts on the substantial identity between the Sardinian infantry and the corsairs and mercenaries represented in Egyptian monuments such as Sherdana. At the same time, numerous votive boats, also in bronze, demonstrate the importance of the sea in Sardinian life »

An identification that can be further substantiated by the Sherdana-Serdaioi name link (people, mentioned in the table of Olympia of the sixth century BC, which made an eternal pact of alliance with the sybarites in an anti-Punic key) and by the fact that the radical serve persist in the toponymy of the island.

The identification between the Nuragic peoples and the Sherdana, or at least with one of them, is accepted [5], it remains to be established what their origin may be given the "Epochal break", underlined by Giovanni Lilliu, between the pre-nuragic matriarchal and hypogean culture and the patriarchal and solar civilization which subsequently came to impose itself on the island. Here historicity in the strict sense (direct written attestations or literary sources) comes into play only marginally. Here, history merges with hierhistory and takes on the contours of myth. Julius Evola in one of his most famous works, Revolt against the modern worldhe stated [6]:

«As far as the emigration of the boreal race is concerned, two great currents must be distinguished, one from north to south, the other - later - from west to east. Carrying everywhere the same spirit, the same blood, the same body of symbols, signs and voices, groups of Hyperboreans first reached North America and the northern regions of the Eurasian continent. A second great migration seems to have gone as far as Central America, but above all to have descended into a land that has now disappeared in the Atlantic region, building a center in the image of the polar one. It would therefore be the Atlantis of the story of Plato and Diodorus [...] From the Atlantic site these races would have radiated both in America and in Europe and Africa [...] Anthropologically it would be Cro-Magnon man appeared in Western Europe towards the end of the glacial period [...] Beyond Spain, other waves reach West Africa and travel along the northern coast of Africa to Egypt or travel by sea from the Balearics to Sardinia to the prehistoric centers of 'Aegean »

To this Evola added that the race directly derived from the primordial boreal stock was divided into two groups: one differentiated by "idiovariation", that is, by a variation without mixing, to which the races of more direct Arctic derivation belonged; and a second differentiated by "mystovariation", that is, by a mixture with the races of the South. To this second group belonged the red race of the last Atlanteans which according to the Platonic tale would have decayed from the divine nature due to their repeated unions with the human race. A story that closely resembles the biblical account of the crossing between the children of God (Ben-Elohim) and the daughters of men who would give rise to a race of giants [7].

This ethnic group, according to the evolutionian perspective, would be at the basis of many civilizations founded along the west-east line (red race of the Creto-Aegean, the Eteicrete, the Pelasgians and the Egyptian Kefti) as well as of some American civilizations that in their myths remembered the origin of their ancestors from the divine Atlantic land located on the great waters. The evocative and fascinating Evolian description coincides with those that are historically identified as the guidelines through which Sardinia was colonized between the Neolithic and Chalcolithic by that mysterious primordial lineage with a precise ethnic character that landed on the beaches of the island and created a centuries-old civilization. also mixing as regards religious beliefs with the chthonic dimension of the indigenous population.

Norax, duce of the Iberians and son of Ermes and Eriteide, according to the story of Pausanias, arrived in Sardinia from the Iberian peninsula where he founded the city of Nora [8]. Before him Aristaeus [9], civilizing hero son of Apollo and the nymph Cyrene, as reported by Gaius Giulio Solino in his work Collectanea rerum memorabilium (known in the Middle Ages as Polyhistor), arrived on the island from Boeotia, perhaps in the company of Daedalus (the architect of the labyrinth in which Minos locked up the Minotaur) and here founded the city of Karalis (today's Cagliari) by educating the indigenous people in agriculture and beekeeping. According to other sources, Daedalus, to whom the ancient Greeks attributed the construction of the nuraghi (called opera dedalee), landed on the Sardinian coasts in the company of Iolaus, grandson of Heracles, and of the Tespiesi. According to Diodorus Siculus, Iolaus was sent to Sardinia where he founded gymnasiums and courts together with nine of the sons that Heracles had with the Tespiadi; the fifty daughters of Tespio (king of Tespie, also a city of Boeotia).

The historian of religions Raffaele Pettazzoni in his fundamental work Primitive religion in Sardinia argued that both Iolaus and Aristeo were nothing more than mythical hypostases of the supreme divinity of the Sardinians identified with Sardos: divine hero, father of the lineage and in turn a civilizer, son of the African Heracles Makeris, who came to Sardinia from Libya and to whom the Sardinians themselves consecrated a bronze statue in Delphi. A hypothesis that derives from the observation that the contacts between the Greeks and the island were always quite superficial. However, this did not stop those who gave the island the name of Ichnussa o Sandals (due to the similarity of the coastal conformation to the imprint of a sandal) to attribute the creation of a civilization and monuments that could not be explained in any other way. This is based on a sort of "classic prejudice" before its time according to which every civilization would be indebted or would inevitably be influenced by the Greek, Mycenaean or Minoan. While, on the contrary, Sonchis, the priest of Sais who instructed Solon on the facts of Atlantis and on the wars that this move towards the Aegean and Egypt, reminded him how the Greeks were but children compared to other civilizations of the past. and to the Egyptians themselves. A prejudice of which Giovanni Lilliu himself was the victim in some respects, who considered the Nuragic civilization as an appendage of the Minoan one. [10]:

«The kingdom of Minos has found its last refuge in Sardinia and the bestial cry of the Minotaur is lost in the labyrinthine recesses of the nuraghi. "

The connection between Sardinia and the myth of Atlantis is therefore not accidental. Sherdana, Cretans, Maltese and Pelasgians would belong to a race, that of the Atlanteans-Mediterranean, coming more or less directly from the center of the island-continent built in imitation of the polar Arctic homeland. And some populations of North Africa (Tuareg, Berber, Cabili) near which numerous and very important persistences of an ancient civilization have been observed, and who live in the hinterland or along that mountain range that the myth identifies with the titan Atlas himself petrified by Perseus after this showed him the head of Medusa .

Pausanias claimed that the Sardinians resembled the Libi (those who lived west of Egypt and wore feather diadems on their heads) both in physical appearance and in lifestyle and armor. But another even more surprising ethnic and cultural similarity is that between Sherdana and Guanches: the Canarian people who carried with them the memory of a cataclysm that destroyed their world and of which the small islands off the African coast were the last remaining strips of land [11].

At the moment, however suggestive, the identification of Sardinia itself with Atlantis, supported by the writer Sergio Frau, it seems difficult to demonstrate despite the evidence of a tsunami that penetrated for over 60 km along the Campidano plain, transforming a fertile territory into a swampy and malarial place and covering important nuragic centers with a blanket of mud and silt. Frau's hypothesis is based on the idea that the island, center of the world and sacred place that to the west of the Mediterranean marks the point where the sun dies, was outside the world then known and included between the Columns of 'Hercules (identified by the writer in the Strait of Sicily) and the Caucasus.

A hypothesis supported by the fact that, as reported in the Timaeus of Plato in which it is said of wars that the Atlanteans waged against the ancestors of the Greeks and the Egyptians, the Sherdana fought against both the Cretans and the Egyptians. After the cataclysm the island turned into a wasteland: a land of the dead. But it remained the island of the fathers for the refugees who arrived on the coasts of central Italy, giving life to the Etruscan civilization. However, it was on this island that they wished to return at the moment of passing through a dip in the sea. This would explain the wall paintings on the Etruscan tombs that refer to the sea and the bronzes that the dead held in their hands.

As fascinating as it is, Frau's hypothesis does not seem to take into account the fact that Plato in Critias place the story of Atlantis nine thousand years before Solon, and the fact that the exchanges, even ethnic ones, between Nuragic Sardinia and Etruria were well developed. This is further demonstrated by recent excavations that have brought to light in the surroundings of Tavolara a real Etruscan settlement.

If the identification of Sardinia with Atlantis is rather problematic, nothing prevents us from considering that the people who arrived on the island through the migration from west to east constituted a new center in the image of the Atlantic one which would thus have assumed the character of the third hypostasis of the primordial homeland. In fact, the idea of the sanctuary / observatory island built by a warrior and spiritual elite at the same time suffering the pain of exile from the pole where man resided in direct contact with the divine, does not seem so far from reality.

The dimension of the sacred

In his work Physical and human geography of Sardinia, Count Alberto Ferrero della Marmora notes the impracticability of some nuraghi as dwellings (narrow space, poor light and poor ventilation) and their poor efficiency from a military point of view (once the village below was burned it would not have been difficult for the besiegers to overcome enemies barricaded inside the nuraghe), assumed their use as places of worship or at least their close affinity with the dimension of the sacred.

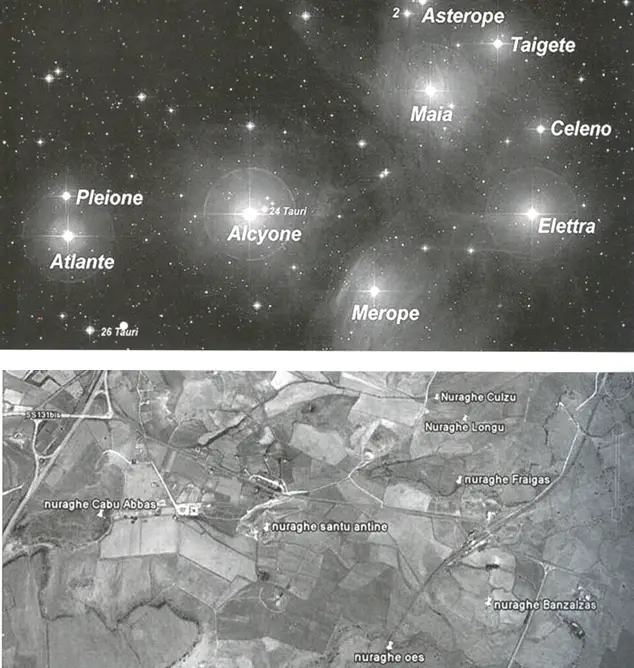

More recent studies conducted by Carlo Maxia and Edoardo Proverbio have tried to demonstrate how the nuraghi were not only fortifications or aristocratic dwellings (monumental buildings that indicated the prestige of those who resided within them), as claimed by classical archeology, but as these "towers of the sky" were used as sanctuaries (fact proven by the vast number of votive figurines found inside them) linked to astral cults or even as real astronomical observatories: that is, as cornerstones of hierocracy intended for the measurement of time. The need to relate time with the motion of the stars is typical of every religious form linked to the rhythms of the cosmos. In fact, the orientation of the access opening of many nuraghi would correspond to the astronomical azimuths calculated from the rising to setting of the most vivid stars in the hemisphere visible to us. [12]. The fidelity of the Sardinian-Nuragic people to the sun, the moon and the stars and the idea that every luminous manifestation had the value of the hierophany therefore appears evident.

The psychological introspection of ancient facts could be favored in Sardinia, more than in other places, by the memory and continuity that is found unchanged in the land and in the men of the island despite the distance in time. The song to the stars of the shepherds who invoke the prosperity of the flocks is nothing more than a reminiscence of that bond that united the Nuragic people to the stars. And that's why the ancient term s'ard nothing else means that "dancers of the stars".

However, it is in funerary architecture that this theory is most strongly confirmed. The tombs take on the role of real astronomical markers by marking the rising and setting of the sun and acting as markers of time and seasons. For example, a gigantic megalithic mausoleum stands near the s'arcu de corru'e boi: a pass between the Barbagia di Ollolai and Ogliastra profiled with ox horns (symbol of the solar divinity taurine, male component of the divine couple of the nuragic religion) behind which the sun rises. Furthermore, the alignment of the 18 menhirs of the funerary area of Pranu Mutteddu marks the east-west equinoctial line, precisely identifying the two northern stations of the moon.

The very exposure of the tombs as well as the menhirs is always oriented towards the east: towards the rising of the sun, to emphasize even more the solar character of a religiosity, however pervaded by spirituality and magic. The central role of the cult of the dead in nuragic religiosity became evident with the monumental "tombs of the giants". And the precise topographical relationships through which the tombs are located with respect to the nuragic towers denote an intimate connection between the two monuments.

The architectural scheme of this funerary construction consists in the presence of an exedra which repeats in front of the building body containing the funerary corridor the half circle of the apse in proportions several times greater. The construction thus recalls the bovine head (once again the solar Bull-God) with the rounded snout constituted by the curved wall and with the horns drawn in the wide crescent exedra. Sometimes, the tomb was surrounded by groups or pairs of betyls (from Hebrew Beith-El - house of God) aniconic, smooth or mammellated, which represented at the same time the guardians of the rest of the ancestors and the hierogamy of the divine couple God Taurus-Sun / Mother-Moon Goddess at the basis of the regeneration of life. The union between the tutelary deities was therefore aimed at the resurrection of the ancestors buried in these megalithic arks, and the stones had the function of metaphysically restoring the life of the deceased. The menhirs affirmed a precise intellectual and organic metaphysical vision to the dimension of the sacred which represented the inviolable and fearful force of the arcane. Through the orthostatic solar symbol the mana: the mysterious force of the divine.

Each of these constructions was carried out following a precise symbolic archetype associated with that used in the Christian era for the construction of churches. The exedra represented a symbolic space favorable to the rite. The tombs of the giants are none other than the tombs of the deified ancestors: gigantic characters in physique, spirit and virtues to which superior and divine heroic qualities were associated. Iolao and the Tespiesi were buried in Sardinia and near their tombs, as reported by Aristotle in Physics (IV, 11-1), incubation rites were practiced [13].

Through immersion for five days in a deep sleep, expression of a timeless condition that the Hungarian historian and philologist Karoly Kerényi [14] defined it as one of the pinnacles of primordial Western thought [15], the sleepers who slept with the gods / heroes, whose bodies according to the story of Simplicius "they remained intact to decomposition as if they were lying asleepFreeing themselves from time to reach a higher state of existence, they were cured of nightmares and obsessions.

The incubation, practiced by the Libyan people of the Nasamoni for divination purposes, was also used by the followers of Asclepius and assumed a central role in the hermeticism in which sleep was regarded as the essential and necessary condition for prophecy. She sleeps with her deceased ancestors so that they appear in the dream to receive advice from them. Sleep indicates a condition in which man is not aware of the passage of time and, in fact, it is as if this did not exist.

Il funerary complex of Monti Prama, seat of the giants kolossoi, as a monument of solar glory of a heroic and spiritual elite whose tombs face east, it had to present itself as one of the places capable of creating the timeless metaphysical space suitable for the rite of incubation.

The Sardinian rite however shows evident similarities with those of other peoples. The land of the Tuareg is strewn with megalithic monuments that the natives claim to be the tombs of an ancient race of giants (zabbar) semi-divine who inhabited that territory in a very distant time. In the proximity of these monuments there is a kind of spirit of the mound (idebui) who helps them in their sleep by providing information on distant relatives or simply by giving information on the lost caravan. A myth that, once again, demonstrates the extraordinary ethnographic, cultural and paleo-ethnographic concordance between the nuragic peoples and the ancestral peoples of North Africa.

Now, Solino reports that a temple was built near the tomb of Iolao in order to worship the one who freed Sardinia from many evils. However, Iolaus, as claimed by Raffaele Pettazzoni, is nothing more than a mythical and Hellenizing hypostasis of the Sardinian supreme god demiurge and thaumaturge known in Roman times as Sardus pater. The simulacrum of this divinity that the Sardinians sent to Delphi as a gift to the most important sanctuary of antiquity, reproduced the original preserved in the Sardos Patoros Ieron quoted by Ptolemy in his Geography (III, 3-2). The temple was located at the mouth of a sacred river identified with the "rio" of Antas. And in this same place where the nuragic sanctuary stood, the Carthaginian invaders built a temple, later renovated under the Roman emperor Caracalla, in which the frontal engraving is still visible «Sardus Pater Babbai».

The idea of pater translates the Carthaginian and Phoenician one of Baal (Lord / God) and with the affixing of the terms muggles o abai (father / ancestor) wanted to openly allude to the divine ancestor father of the indigenous peoples. The tomb of Iolaus is the temple of Sardus pater; divine hero who crosses the land of Sardinia benefiting the people of him. The warriors consecrated their swords to him in the instant preceding the battle.

The Iolai were the people of Sardinia who suffered most from the Punic colonization. However, the invaders, both Punics and Romans, recognized the value of this people and as a sign of respect they inserted the supreme indigenous God into their pantheon. On a votive column found near Pauli Gerrei and dating back to the second century BC, a certain Cleone in charge of the salt pans, thanked for his recovery to the Sardus pater associating it with Eshmun (Phoenician version of Asclepius).

Raffaele Pettazzoni argued that the Sardinian religion, characterized by a constant tension towards the sky and its stars, was not a true polytheism, but a sort of imperfect monotheism [16]. Il Sardus pater it's not a primus inter pares. He has an exalted and absolutely unique position from which he dominates the entire religion of his people. Next to the supreme God there are a collectivity of divine figures inferior to him who could still be identified as attributes of him. And only anthropomorphism, quite foreign to Sardinian sacred art, can transform divine attributes into as many divinities.

And at the same time, the Sardus pater he is a mortal god on a par with the pre-Hellenic Cretan god subsequently associated with Zeus. However his death was a regeneration and a transfiguration to a higher degree of being: death as the "last clarification" of the hermetic tradition. He, abandoning the human bond, reached a divine state and freed himself from every bond, becoming stronger and more noble than his cosmic parents, heaven and earth (sun and moon). The divine idea of the Sardus pater it is not unlike that of Tirawa; the father spirit of the North American Pawnee. And with them, the nuragics shared the belief that the stars of the sky were as many manifestations of the divine.

After all, according to René Guénon, any true tradition is essentially monotheistic in that it affirms above all the unity of the supreme principle from which everything derives and depends. And the Sardinian one was an imperfect monotheism perhaps because it was influenced by forms of chthonic demonism. In fact, the origin of the myths of Janas (fairies that in their houses of rock weave gold fabrics with gold looms) or Orgia Rabiosa (a witch gone mad after the death of her child who closely resembles the myth of Niobe) [17].

This monotheistic idea is not in contrast either with the animistic character of Sardinian religiosity or with the idea of the divine couple at the basis of the regeneration of life. That of the divine couple is a religious model that is reflected in other areas of the Mediterranean: from the Cretan civilization in which the Bull is rendered in the womb of Pasiphae (erotic-lunar goddess and wife of Minos) through the wooden cow built by Daedalus, to the 'Egypt where the god Horus was also called Kamoutef (Taurus), up to the myth of Attis and Cybele.

In Sardinian civilization, the lunar Mother Goddess is an all-seeing (she is also called "goddess of the eyes") and regenerating deity. The solar Bull God is complementary to her and her horns and discs are her reference symbols. But the Mother Goddess besides being a deity of life is also a deity of death. The return to the womb of water indicates the completion of the cycle of life and the return to the maternal divinity. This is the theme of death as a passing over the water whose sign is the spiral [18]. The spiral motifs suggest the eschatological idea of the afterlife and indicate the way to the resurrection once again through water: a symbol of life as its original element and of infinity [19].

The passage on the water as a prerequisite for rebirth it is found once again in the hermetic tradition: "The figures of the" Saved from the waters ", of those who" walk on the water ", and also the crossing of the sea or the current (whence also all varieties of navigation symbolism), and pushing the current backwards. The latter, according to the Corpus Hermeticum, is the direction to reach the state of those who are in gnosis " [20]. Here takes place the birth according to the essence of those who are and no longer become, like the mythical God / hero of the Sardinians.

The hierogamy of the divine couple took place on the altar of the ziggurath of Monte d'Accoddi: megalithic construction dating back even to a pre-nuragic age. Linked to the idea ofaxis beat and of the tree of life, on this altar the solar Bull-God descended to ritually unite with an earthly priestess image of the Mother Goddess [21].

The structure of the monument, 10 meters high and built on two terraces, recalls, albeit in a reduced version, that of theEtenemaki of Babylon, more than 90 meters high divided into five terraces topped at the top by the altar with the golden bed on which the god Marduk lay with a priestess following his nocturnal descent from heaven. However, in addition to the construction techniques, this place of celestial contemplation shows substantial differences compared to the Akkadian-Sumerian model: the presence of two menhirs (one in white limestone and one in red sandstone) and a large spherical stone covered with micro-bowls that they are assumed to describe the constellations. The two menhirs respectively indicate the two celestial stars (the moon and the sun), while the spherical stone is a omphalos: a symbol of the center of the world. As Guénon recalls [22]:

"The symbol ofomphalos it could be placed in a place that was simply the center of a specific region, a spiritual center, moreover, rather than geographic, although the two may coincide; but, in that case, that point was truly for the people who inhabited the region under consideration, the visible image of the center of the world »

THEomphalos materially represented as a sacred stone, it is both the house of God and the gateway to heaven. In addition, according to the scholar Eugenio Muroni, the symmetry of the altar reproduces the stars of the Southern Cross, today no longer visible in the region due to the procession of the equinoxes [23].

Several other places have marked the sacred geography of Nuragic Sardinia. This is especially the case of sanctuary cities built around the sacred wells, seats of the cult of water. In Sardinia both spring waters (as demonstrated by the fact that each village was built near a spring) and rainwater, by virtue of their common divine origin, were considered equally sacred. There were real operations aimed at propitiating storms. One of these was the rite (still carried out today by the shepherds of Abini Teti) of beating the rocks with sticks to wake up the spirits and induce them to unleash the storm. An "evocation" that shows remarkable similarities with that of the so-called "rain makers" (rainmakers) North Americans.

There was also a kind of nuragic baptism as a purifying rite for newborns who, through washing in sacred water, removed all forms of physical and psychic impurity from the child. And they also existed ordal rites (proof of water) which have remarkable similarities with the Urtheil of the Germanic peoples. Water was a kind of dispenser of divine justice and losing the light of the eyes as a result of this test, essentially consisting of bathing them in sacred water, it carried within itself the demonstration or sanction of guilt. While a null result, in addition to proving innocence, would have increased the moral and spiritual caliber of the one who was subjected to it.

Traces of the religiosity of water are found both in North Africa as well as among the Arabs, both in the pre-Islamic era and in the age following the Revelation. The same term Sharia indicates the way to a source of water in the desert and therefore to salvation. And it is widely believed that water can drive away evil spirits (jinn).

The sanctuaries of Santa Vittoria di Serri and the well of Santa Cristina di Paulilatino are the most evocative and fascinating monuments of the Nuragic civilization linked to the cult of water. Set in a majestic and enchanted solitude between mountains, water sources and forests, the sanctuary of Santa Vittoria presents itself as an ideal site in which to celebrate the presence of the divine among men. The geographical landscape itself, an entirely consecrated plateau, served as an altar through which to relate to the feeling of the sacred. [24]. The well temple was the main building of the sanctuary city and annually celebrations, rites and sacrifices took place in its vicinity. The dances themselves took on a spiritual value of religious exaltation [25]:

"Music, dance and songs were ritually linked to the services of worship and the religious manifestations of the feast, inside or outside the temples, or in the broader scope of the sanctuaries [...] round dance, variety of Mediterranean sacred choral dance, still persists in Sardinia, articulating itself in varied rhythms and movements, now slow, now acrobatic, now in religious cadence, now in magical-ecstatic frenzy »

In these sanctuaries the pilgrims brought their ex-votos (the bronzes) which were deposited in the atriums of the temples and to which they added liquid and solid offerings (honey, bread, oil and cheeses). Il sanctuary of Santa Cristina [26] instead it shows some interesting archaeo-astronomical connotations. In this regard, Guido Cossard noted that [27]:

«The relationship between the base and the height of the dome of the well coincides with a very small margin of error in astronomical geometry. The line that starts from the north point of the base of the dome and arrives at the opening at the top, forms an angle that coincides with the angle with which the moon crosses the meridian on the day of the northern greater lunar lunar; that is, the extreme point that reaches the moon in its apparent motion in the sky. In analogy to the solstice, the lunistice defines the moment when the moon reaches the maximum declination of its monthly cycle. »

Arnold Lebeuf in his studio entirely dedicated to the Santa Cristina well defined it as a real one "Mirror of the sky". The researcher also calculated that every 18 years and 6 months the moon reflected on the bottom of the well and that the same edges of the stone rows of the steps were used as an instrument for measuring the lunar motion also for the purpose of predicting its eclipses. [28]. It appears so clear that the observation of the lunar motion, linked to the Mother Goddess, had more strictly ritual characters than the solar cycle linked to agricultural practices and the cyclical regeneration of life.

Conclusion

Far from the barbaric connotations that Pausanias attributed to it, the Sardinian civilization had a peculiar character intrinsically connected to the physical and humoral specificities of the land they inhabited. The absence of a written tradition does not necessarily imply a lesser degree of civilization. An exclusively oral tradition is often associated with a spiritual doctrine and a properly metaphysical conception inexpressible through written language but which in some cases requires the instrument of the symbol. This may be the reason why a civilization that has demonstrated a high level of development on the social, military and architectural level and a lifestyle deeply permeated by the dimension of the sacred has not, however, produced a written tradition.

In pre-nuragic art, and especially in that of the culture of San Michele, the idea of man in relation to the divine was clearly expressed through ceremonies, rites and myths. The primordial geometry of artistic forms was nothing more than a principle of abstraction aimed at overcoming the natural specific to reach the universal level of the supersensible. The Nuragic age, while recovering a certain anthropomorphism (characteristic of a heroic civilization) that was distinguished in the creation of votive figurines [29], kept intact the ideal of conceptual abstraction proper to an intellectual perspective in which the meta-historical aspect was privileged. This overcoming of nature through the symbol was prompted by a precise desire to understand the world and its phenomena through a metaphysical interpretation. And in the end, the immediate metaphysical truth "Being is", translated into spiritual or religious terms, cannot but transform itself into "God exists", and therefore in the direct ascertainment of the divine presence. A presence that permeated every aspect of the inner and outer life of a people who lived on a plane inclined towards transcendence.

Note:

- M. Eliade, History of religious beliefs and ideas (Vol. I), BUR Rizzoli, Milan 2006, p. 133.

- M. Pittau, The dominion over the seas of the Tyrrhenian peoples. Nuragic Sardinians, Pelasgians, Etruscans, Ipazia Books, Dublin 2013, p. 42.

- G. Lilliu, The civilization of the Sardinians. From the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi, The Maestrale, Nuoro 2017, pp. 459-460.

- VG Childe, The Bronze Age, Cambridge University Press, London 2011, p. 132.

- Giovanni Lilliu identifies at least four different Nuragic peoples who lived in different areas of Sardinia: the Iolai (Campidano); the Sardinians (south); the Balari (Logudoro); the Courses (Gallura).

- J. Evola, Revolt against the modern world, Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome 1998, pp. 242-243.

- See in this regard Genesis (VI, 1-8).

- Pausanias, Periegesi of Greece (X, 17-5).

- Born in Libya, where Apollo led Cyrene after having kidnapped her, on the orders of Hermes he was raised by nymphs who taught him the art of herding and beekeeping, while the centaur Chiron introduced him to the art of hunting. Falling in love with Eurydice, Aristeo tried to make her of her, but this running away from her trampled on a snake that killed her with her poison. The nymphs out of spite destroyed his hives. However, the demigod, at the suggestion of his mother offered a sacrifice to the muses to appease their anger and, returning to the site of the holocaust after nine days, found a swarm of bees emerging from the carcass of the sacrificed bull, so that he could begin to produce again. honey. A statuette of Aristeo was found in Dule in 1843 as reported in the text by Giovanni Spano Aristeo in Dule.

- The civilization of the Sardinians. From the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi, therein cit., p. 471.

- In this regard, see M. Maculotti, Enigmas of the Mediterranean: the Guanches, the Peoples of the Sea, Atlantis, on AXISmundi.

- C. Maxia - E. Proverbio, Astronomical orientations of nuragic monuments, Extract from the Reports of the Lombard Institute, Academy of Sciences and Letters, Vol. 107, Milan 1973.

- See B. Udai Nath, Parmenides, priest of Apollo: the "incubatio" and sacred healing, on AXISmundi.

- See. K. Kerényi: "The mythologem of timeless existence in ancient Sardinia", on AXISmundi.

- K. Kerényi, Myths and Mysteries, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin 2010, p. 122.

- R. Pettazzoni, Primitive religion in Sardinia, Carlo Delfino Publisher, Sassari 1981, p. ninety two.

- Grazia Deledda in her novel canne al vento lists all the mythical characters linked to Sardinian culture and folklore: Janas, hot (women who died in childbirth), theslaughterer (elf with seven caps within which he hides a treasure), giants, orcs and steel-tailed vampires. The author from Nuoro writes: «on full moon nights all this mysterious people animate the valleys and hills; man has no right to disturb him with his presence, as the spirits respected him during the course of the sun ».

- See M. Maculotti, The symbolism of the Spiral: the Milky Way, the shell, the "rebirth", on AXISmundi.

- The civilization of the Sardinians. From the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi, therein cit., p. 269.

-

J. Evola, The hermetic tradition, Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome 2002, p. 77.

- G. Lilliu, Before the nuraghi, in AA.VV., Society in Sardinia over the centuries, ERI Edizioni, Turin 1967, pp 15-16.

- R. Guénon, The King of the world, Adelphi Editions, Milan 1977, pp. 88-89.

- In this regard, see E. Muroni, Monte d'Accodi. The forgotten ship of a lost homeland, The Third Millennium, Rome 1970.

- The Nuragic Sardinians also adored the trees of the sacred woods populated by fantastic creatures and the spirit of the forest that the Romans identified with the Latin god Silvano. In this regard, Gregory I the Great, irritated by the Sardinians' resistance to conversion to Christianity, wrote: "barbaricini omnes, ut senseless animalia vivant, Deum verum nasciant, line autem et tombstones adorent».

- The civilization of the Sardinians. From the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi, therein cit., p. 661.

- It is curious to note how the places of the nuragic sanctuaries were subsequently transformed into Christian places of worship. Usually the Christian bishops who settled in the most populous cities near the coasts attributed to Christian saints and martyrs, local and not, miracles performed in the vicinity of the old nuragic sanctuaries in such a way as to justify the continuation and resistance of certain ancestral rites in the Christian era and both to support the spread of the new religion among the population. Thus Christian saints and saints were connected to the ancient religiosity of the Nuragic waters and sacred sources. In this regard you can see A. Massaiu, The distant origins of the Sardinian carnival, on AXISmundi.

- G. Cossard, Lost skies. Archaeoastronomy: the stars of the ancients, Utet Editore, Turin 2010, p. 98.

- A. Lebeuf, The well of Santa Cristina. A lunar observatory, Tlilan Tlapalan Editions, Krakow 2011, p. 151.

- Of particular interest are the hyperanthropic ones found in the sanctuary of Abini Teti, with four eyes, four arms or four legs, tending to reflect a semi-divine condition and increased strength in the senses and in the body.

Bibliography:

- Various authors, Society in Sardinia over the centuries, ERI Editore, Turin 1967.

- True Gordon Childe, The Bronze Age, Cambridge University Press, London 2011.

- Guido Cossard, Lost skies. Archaeoastronomy: the stars of the ancients, Utet Editore, Turin 2010.

- Sergio Frau, The Pillars of Hercules. An exhibition, the testsNur Neon, Cagliari 2006.

- ID., Omphalos. The first center in the worldNur Neon, Cagliari 2017.

- Karoly Kerenyi, Myths and Mysteries, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin 2010.

- Arnold Lebeuf, The well of Santa Cristina. A lunar observatory, Tlilan Tlapalan Editions, Krakow 2011.

- John Lilliu, The civilization of the Sardinians. From the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi, The Maestrale, Nuoro 2017.

- Leonardo Melis, Shardana. The Peoples of the Sea, Ptm Publishing, Mogoro 2002.

- Eugenio Muroni, Monte d'Accodi. The forgotten ship of a lost homeland, The Third Millennium, Rome 1970.

- Massimo Pallotino, Etruscology, Hoepli, Milan 2016.

- Raffaele Pettazzoni, Primitive religion in Sardinia, Carlo Delfino Publisher, Sassari 1981.

- Giangiacomo Pisu, S'ard. The dancers of the stars: symbolism, shamanism and cosmic religion in the Sardinia of the nuraghi, Ptm Publishing, Mogoro 2014.

- Massimo Pittau, The dominion in the seas of the Tyrrhenian peoples: Nuragic Sardinians, Pelasgians, Etruscans, Ipazia Books, Dublin 2017.

- John Ugas, Shardana and Sardinia. The Peoples of the Sea, the allies of North Africa and the end of the great kingdoms (XNUMXth - XNUMXth century BC), La Torre Editions, Cagliari 2016.

2 comments on “Sacredness, myth and divinity in the civilization of the ancient Sardinians"