There is a chain that goes from the invisible and immobile "nourishment" of the mineral, to the primordially articulated one of the plant, to that of the herbivorous and then carnivorous beast, in which the original fall manifests itself for the first time in dramatic form, to the human one, in which the tension between guilt and redemption is greatest

di Daniele Capuano

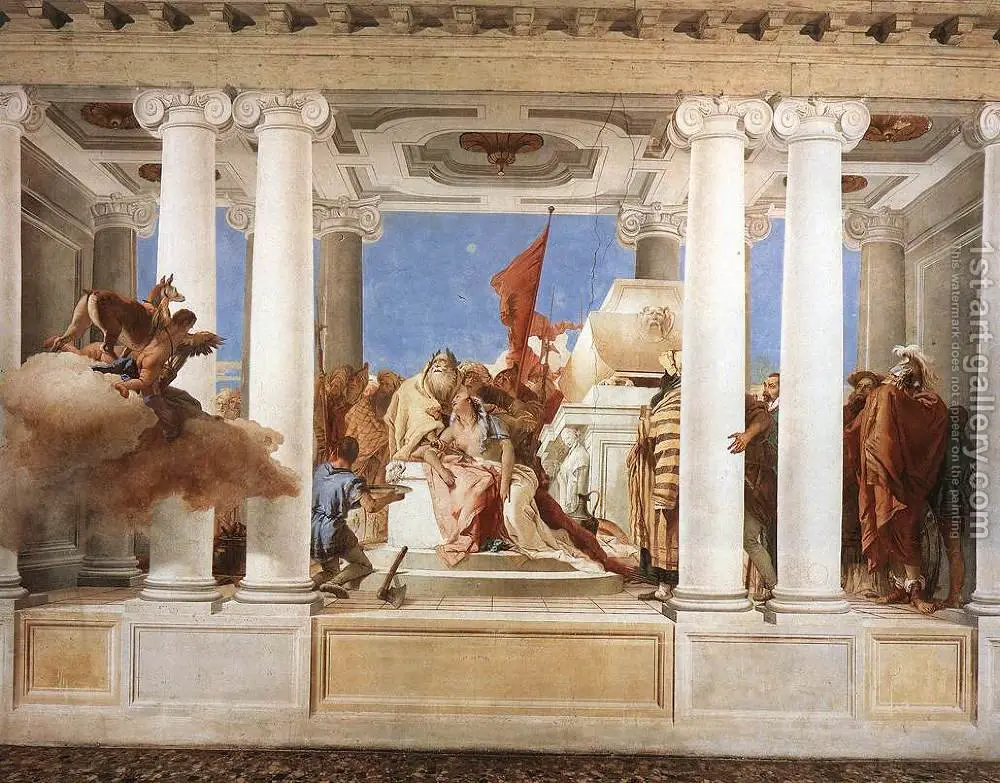

image: René Magritte, "The Natural Graces ", 1964

It is almost impossible to raise ethical objections to vegetarianism. After all, ethics is an invention or a perspective that does not belong to archaic integrity, in which almost all human actions sink, human rituality as a living, symbolic synthesis of celebration and theurgy, acceptance and criticism, repetition and renewal. In ancient life, vegetarian nutrition is part of a spiritual path that is a unitary link of vows that are difficult to separate: usually sexual abstinence accompanies it and as a whole is configured as a break with worldly habits, which are based instead on a more or less conscious ritualization of carnality, of passions, of samsara - and therefore of physical love, of the killing of men and animals, of the meat diet.

The act of animal sacrifice recalls and preserves some features of the even more ancient, archaic world, in which hunters knew by preying and preying knowing, in a tragic intertwining of aids and exaltation, anxious sensitivity and brutal courage: but how actus tragicus, as an archetypal theatrical representation, as a rite that founds and shapes the community, the killing of the animal crosses all cultures, the nomadic, the peasant, the sacral and then semi-profane and then imperial urban.

Sacrificing (literally: "making it sacred", from Lat. sacer-facere) the animal implicitly recognizes its similarity with us and at the same time its difference: the animal is a relative of ours, a divine relative, veiled, mysterious - we too are animals, we have a cognitive structure similar to yours, yet the carnivorous animal does not sacrifice and the herbivore does not eat meat. Man, a ritual animal, does not know - except in the space of some orgiastic rites - the exaltation of the predator who, after chasing the prey, sinks its teeth into its jugular or cuts it to pieces still alive.

The sacrifice says: this being, which is my relative, is not my property, belongs to the gods, is a divine mediator; by killing him I deliver his invisible substance, the partie de Dieu, to the invisible, and I introduce in me something that mediates between death and life, a dead body still quivering with life, which by preserving my life and nourishing it is transfused into it, nourishes itself of it. Nourishment is the assimilation of the soul, of an animal, in the case of flesh feeding through the animal itself. What matters is that it is a rite, therefore a living nucleus that the various interpretations do not exhaust: if we say that the animal is assumed in a higher sphere, involved in a transmuting circuit through the presupposition of its implicit consent (which is implicit admission of the animal in the domus human, and therefore of domestication), let's tell the truth, but not the whole truth.

After all there is no mythical reflection that silences the connection between a fall from the excellent primordial state and the priestly killing of animals from which to draw nourishment: but this is not enough, because every element of human life participates in this fall, indeed, what we call man is this fall; also the attempt of a spiritual elite to re-approach Eden by abstaining from animal flesh and from all sorts of violence.

Famous anti-vegetarian objection: "Could it be that picking and eating vegetables is an act without violence?". We cannot base a spiritual vow on conjectures relating to the sensory and cognitive structure of a being other than us: of course we presume to understand more about the animal, but it is impossible to separate it too clearly from the vegetable, which almost certainly does not lack perceptions. At the root of classic vegetarianism there is not the "antispecism" of some contemporary vegetarians, which is contaminated bylimitlessness [1] proper to modern thought, very evident for example in the evolutionary dogma (which sometimes "secular" vegetarians indulge): a consequent antispecism offers the right to the objection just mentioned.

On the other hand, no one denies that nutrition is or implies the destruction of another living form, although at the same time almost everyone has confusedly present a notable difference between killing an animal and the harvesting and preparation of a vegetable. But the difference will be only in the fact that the animal screams and resists visibly and audibly, as he observes in a masterful piece of rhetoric. Plutarch, while the plant is silent and immobile, or at least it does not give us perceptible signs of rejection? This too is quite weak: we know that plants give very subtle signs of their "will", as you would say Schopenhauer, or their "soul", as he would call it Closer. But there is a difference: every man feels that in the charitable relationship with another being must enter a fallible and open but effective consideration of the way in which the second seems to perceive and feel the world.

And yet this too is not conclusive: at the basis of human culture, and of the most ancient and profound spirituality, there is not a purely sentimental compassion, but a compassion rooted in a higher, divine vision of living beings. Not that archaic compassion completely disregards the sensitivity towards the states of being that is its object, on the contrary: but the root, in fact, the foundation, is another. Those who have broken a law are punished by making them suffer in view of their transformation, which is not exactly "their good" in the modern sense, but in any case presupposes their adherence to a sacred pact, an alliance, a common vow. It acts as if its status is something, not voluntary in the sense of ethics, but to which it has been or can be or must be initiated: it is assumed that the end of all birth and nature is a rebirth and a resurrection.

Similarly, in a different but not contrasting way, the animal is considered, which is not part of the community in the same way as other men, but is not even excluded from it (both the free and wild animal, divine spark that we can capture pushed by a necessity that is also a game - why the world itself is a game in which divine unity is communicated to beings in an always open opposition, in a relationship that is always polar, antinomic, ambivalent - be a fortiori the domesticated animal, over which man exercises a lordship that unlike the divine one, of which he is an image, is subject to very heavy and risky bonds, since man is also an animal), as someone who has implicitly consented , silently, to the human covenant, to culture and to human worship, for which man, however, bears the responsibility, culpability: and nutrition is this mortal test, this ordeal that has nothing guaranteed, even if its tragic substance fatally induces the human actors to harden the heart, to the banality of evil.

In other words, eating animals is a sign of falling, such as the division of sexes and wills, and therefore the existence of power and the court and inequality: but human culture can only open up a way in the fall, and live in the tension between the Thomas of the massacre taken for granted every day and the sattwa of the spiritual elite who seek to repair the Edenic image through renunciation and internalization. The rite that mediates is none other than the life of man in his samsaric fragility, the life of the "people" or ordinary, common life, in which the violence of the fall is reactivated in the forms that sacrifice raises in a space of possibility and necessity, the tragic (possibility opened by necessity): a space so dynamic that it is confused each time with the descending movement of the fall, even though it is virtually its transmutation.

So the fascination of animal sacrifice comes down to this, and it is no small thing: the sensus communis, il gentium consensus as an at least implicit desire to "get one's hands dirty" with the samsara, with the fall, to direct her to his telos transmutatory. For this reason the prophetic religions tend to preserve the flesh diet, sanctifying it: because the prophetic is the descent of the vision in the everyday, in the popular, it is the poor and powerful sister of the resurrectional alchemy; and instead the Gnostic or sapiential religions tend to propose directly an extension of the vegetarian, monastic, Edenic diet, to the greatest possible number of "faithful" and practitioners. In the prophetic there is a Dionysian smell of blood, an archaic exaltation under the species of the ordinary, the material and the carnal: the vision must be leaven, alchemical ferment.

I suspect that the Orphic-Pythagorean-Empedoclean doctrine of the transmigration of souls, which in the classical era, according to these initiates, should have persuaded one to abstain from meat, in the archaic era it was the basis of a general vision of nourishment, including meat. If we feed only on souls, according to the Inuit saying, and if the souls or monads are in continuous transmigration, in a perpetual flow, then everything is in everything, and everything (every act) will be a crossroads in which they meet and give to which all relations are projected: therefore there is a chain that goes from the invisible and immobile "nourishment" of the mineral, to the primordially articulated one of the plant, to that of the herbivorous and then carnivorous beast, in which the original fall manifests itself for the first time in dramatic form, to that human, in which the tension between guilt and redemption is greatest, the pontifical, priestly arch which connects the land of need and cruelty to the heaven of charity and harmony; to finally reach mystical cannibalism, the Eucharist that reconstitutes Man through Man himself. The predator imitates the cry of the prey, identifies with it: the sacrificer projects himself on the altar, and in the end he always eats himself, or in any case he eats Man, because assimilation presupposes similarity and indeed the mystical identity.

It is impossible for fallen man to recover nature, to be natural, to perform natural acts. In the De radiis al-Kindi he observes that animal sacrifice has theurgic, magical efficacy, precisely because the animal suffers a death against nature, desired by the man who thus takes on his risk, placing himself on the evanescent ridge between black and white magic, witchcraft and propitiation.

Food is eaten by beings and eats them: this is why it is called anna. (Taittiriya-Upanishad)

IEating is a circle, a flow. The first body or sheath is one made of food. The world continually eats and is eaten: there must have been a mithaq pre-existential, in which each species has manifested its assent to creation as it is - and at the same time the animal life, the representative, sensitive, sentient life, the dream life of the animal (of the dream because its desire determines, it delimits the objects, the essences, separating it relatively from the root, from the unitary source - this is its anguish) it resists in anguish the reabsorption in the circle, opposes an individuality to what is common and transindividual. This anguish expresses both the fall, the rupture of harmony, and the divine ecstasy in creating, the abyss of amazement on which creation stands out.

Nevertheless, animal suffering is pure and its anguish is (according to Rilke) anyway aimed at the Outdoors, at unity with God; human self-awareness and reason, which give consistency to guilt and prepare the conditions for a now unlimited, all-pervasive anguish of death, make man the crux of the universe, the critical and decisive point, the lowest point which is the point of ascent, the criminal who becomes a priest (and the priest who has become a criminal). In him the circle of food reaches the culmination of its own tragic paradox: if the animal predator, with his adventurous lust, is invested with a sort of freedom to hasten nature into his prey, the hunter-breeder, hero-priest man , he feels in himself an unlimited freedom that coincides with the unlimited anguish, his potential omnivorousness is the dazzling expression of his passion for life and knowledge, of his super-animality (and sub-animality), and limits himself only to transform the unlimited into the infinite, to build bridges to unity.

Man is truly the animal melancholy, the sick animal: after a certain level of suffering and guilt, death is experienced, the finite cannot be tolerated, everything must be impregnated with meaning, with upward movement, with light that torments and alleviates.

Note:

[1] Unlimited in the sense ofapeiron Pythagorean: the indeterminate, the potential infinite, not the current one: modern "quantitative" science is marked byapeiron, since it tends to exclude or marginalize the qualities, the pears, the "limit" which (according to the ancients) is what shapes the unlimited and makes knowledge possible.

Appendix:

One might think that theonus probands fall on the carnivore, that he must justify himself: but it is not good to talk about accusations and defenses, it is appropriate to talk about life, and the light that can illuminate it.

The choice to abstain from meat often comes from an anxious and whole attention to nourishment, and intensifies and prolongs it: the clear-hearted vegetarian will not fall into the trap of self-righteousness, he will feel that not even eating millet and cabbage is innocent. If you let your own shape pneuma - the imagination living in the breaths of subtle physiology - from one's diet, one cannot fail to understand that everything is dynamically interconnected, and that therefore whoever tears up his roast beef is not separated, with an angelically clean cut, from a table loaded with fruits of the earth. Over time, wheat and chaff are mixed in each one, because each is the field of the Gospel parable.

If you really want to ask the question of who is saved, you save (classically: initiated into the Little Mysteries) he who transforms as much evil as he can into his own suffering: that is, he who does not seek to give but to receive suffering, to transfer suffering from the visible altar to the interior and invisible altar. However, by doing so, one does not seem to escape from the sacrificial logic, but rather it is exalted and exasperated: one is freed from the sacrifice of the animal only by sacrificing oneself, or the animal in oneself.; we stop stealing food when we make ourselves food, when we prepare ourselves like bread and wine on the table of time and space.

Sometimes one gets the impression that the vegetarian is sentimental, and identifies evil with suffering. Evil is undoubtedly the suffering itself, suffered or inflicted, which does not open to the light. When it is inflicted, for example as a penalty, one must suppose in the subject a will or at least a possibility of opening up to the light: and this only when it is strictly necessary. In the case of the animal, since it cannot be made a full part of the human community, it is very doubtful that this need arises. Therefore, as the law teaches, in doubt it is better to refrain from giving pain or death.

A subtle objection, bordering on sophism, which moves to the vegetarian, at least when the controversy moves away from morality and turns to metaphysics, is the certainty with which he speaks of plant nutrition (a development of the accusation of self-righteousness). Certainly the vegetable does not experience "death" like the animal. When we eat it we destroy it, no doubt, but we must atone for its destruction without purifying ourselves from killing. And it's not just out of necessity that the vegetarian philosopher he eats it, separating it from the earth and assimilating it to himself: the vegetable is so far from man, from the conscious animal, that the latter can legitimately believe it is being offered so that it may draw life and light from it; light is the only "end" of the vegetable, inside and outside the earth.

If the vegetarian does not grasp the plant just because he cannot resist it, only because it is a lamb that does not bleat, he takes it out of his womb and introduces it into his with the knowledge that he will live and die from it: his every act and thought will try to to make her rise again as the purity and the uprightness that are manifested in her, whether rooted or uprooted.

Finally, as regards vegans, those who abstain from animal products even when they do not involve killing (milk, eggs, honey, all supreme symbols of the divine, especially of the Goddess), the vegetarian approves them if they do not absolutize the their contingent radicalism, their testimony. The crimes against which vegans testify, or can testify, are intensive industrial farming, slaughter aggravated by horrors of totalitarian extermination, slavery more opaque than the ancient one, covered by the most nauseating hypocrisy. But raising animals, if you do not kill them and rob them of the necessary, is not, for the vegetarian, an impure act in itself: indeed, this is one of the few legitimate ways of welcoming them into our community.

In a world governed by love and wisdom, there is no, or has no value, an abstract purity, merely negative. The bios philosophikos, the existence in love with Sophia, includes violence in itself, it is the humble glory of a living equilibrium, of a transparent peace that cannot but be tinged with the blood of the royal purple, even - and perhaps above all - when the hands refrain from pouring it.

A comment on "Reflections on vegetarianism"