The parody does not destroy the chivalrous tale, it confirms it by overturning it: Kafka was the knight of the destructive absolute and at the same time of the irony that damn and save.

di Daniele Capuano

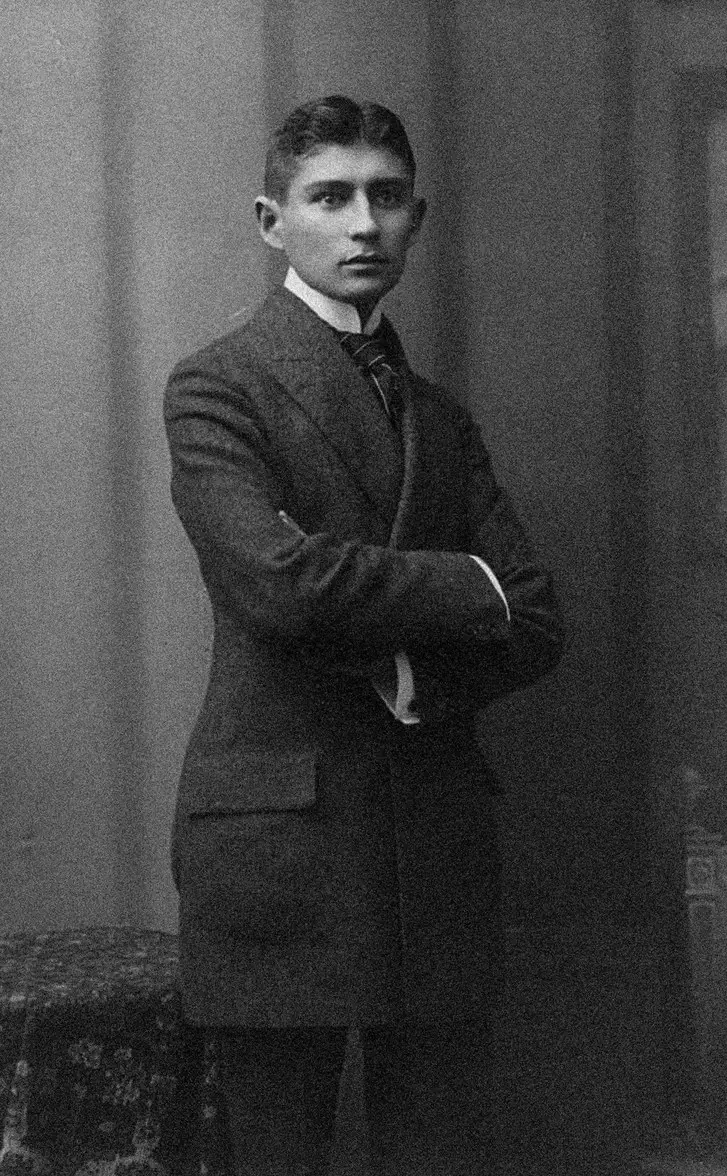

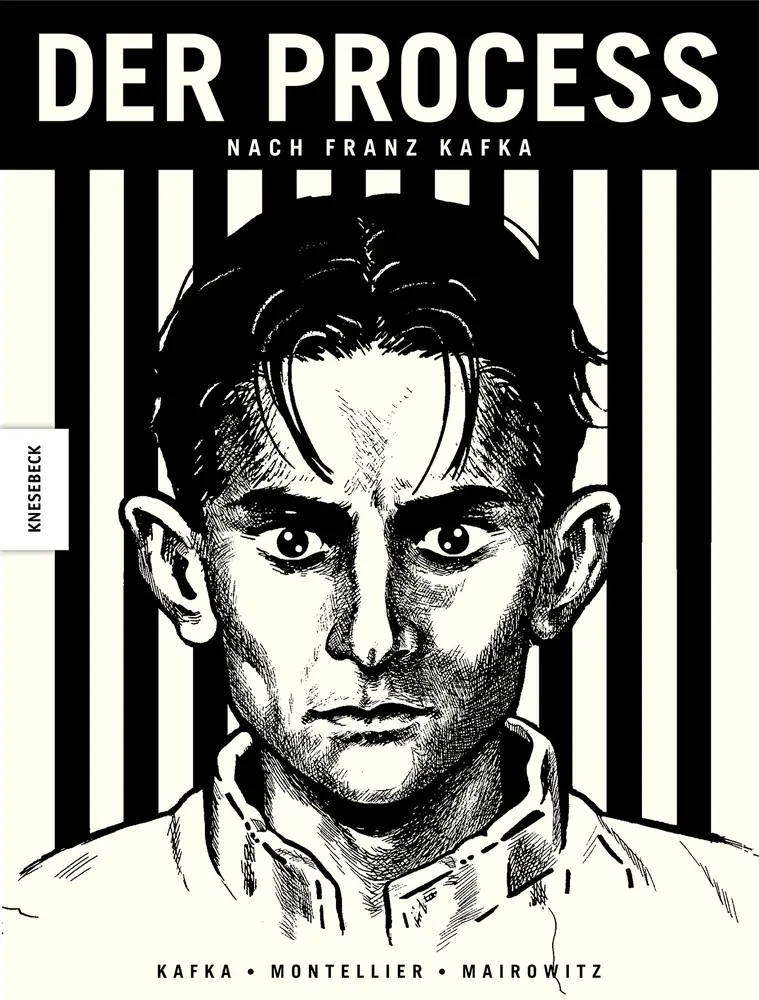

I'm not the first to see in the Prozeß by Franz Kafka an anti-Parsifal [1] - or rather, one parody (black and shiny like the feathers of a crow, kavka) of the legend of Parsifal. The following pages will attempt to look at some of the ramifications that emerge from the seed of this intuition.

Jungian speaking, Josef K. experiences a conflict on the egoic level and not an antinomy that makes the transcendent function of the symbolic vision flourish.. He misses the tertium offered to Parsifal by the hermit Trevrizent and powerful images such as that of the woman with the dead husband on her knees [2]. Or he misses it look able to grasp it - the astral and hermetic gaze of the ancient heroes, the heroes of the epic, of myth, of fairy tales.

The painter Titorelli is obviously Titurel, the keeper of the Grail, who with oracular-Talmudic ambiguity exposes to him the functioning of the Court, the dark, occult forest of karma. Huld the lawyer ("Grace") makes his client a dog (Dog), and like a dog Josef K. will die: canine death, the most indecorous, is also what the Tibetan tantra considers the most suitable for the sage [3].

In Josef K.'s world, which is ours, the Grail is death, as the Messiah is death for the characters of Isaac Singer [4]. Like the peasant - lo ʻAm ha-aretz or rabbinic "people of the earth" - in the apologue of the priest, dying Josef K. sees the light of the Law, the light of the Grail, in the lunar disk (R. Steiner on the cup and the Grail host as a lunar symbol) [5]. The man who leans out the window is the question asked too late, in limine mortis.

The priest tries to teach Josef K. that the Tribunal is not the adversary of a conflict to be sustained with the forces of the ego - which then obviously will end up relying too much on the help of "women", on the irruptions of the Soul. who have shadowy characters, seductive-repugnant, prostitute-messengers - but the field itself of its symbolic struggle, of its existence. The Tribunal is the world as an arena for a spiritual struggle: "it takes you when you come, it lets you go when you go"- thus, according to Zhuang-zi, he is a wise man with phenomena, the" ten thousand things " [6]. The Tribunal "does not want anything from you", it is not separated from you, it does not capture you from the outside [7].

Josef K.'s trial is neurosis as inauthentic suffering. The ego that has pushed away from itself what he does not want sees it returning as shadow and fate. He is not as crazy as Parsifal, even if he appears more and more improvised and self-destructive, and like him he is fatherless and motherless. Not asking the question about the meaning of the Grail, of the Law, makes one cursed: there is no need for anything else to be condemned.

The Good Friday of Josef K. is not the mirror of Golgotha upright and offered by the hermit Trevrizent, it is the same ritual slaughter that he undergoes at night at the hands of two "guitti" [8]. Our post-Christian era is more christ of the above: the removed or rejected Christ returns in the form of a scandalous, canine, infamous identification. He's a apocalyptic carnival: the parody of Production it made Kafka laugh as he read it, as well as his listeners [9].

The Tribunal is heaven as the writing of the fate, the karma. Josef K.'s name is engraved in letters of fire [10] like that of Parsifal on the Grail cup: but Josef K.'s cup is his dreamed grave. The shame that seems to survive him [11] it is not a leaven of solar redemption, like that of the Grail, but a lunar seed inserted in the karmic current, destined to bear fruit beyond the comic and neurotic limits of the doomed egoic consciousness [12].

Il koan of the apologue of the Door of the Law remains, like the shame that rises over Josef K.'s torment at night, like the rock to which Prometheus is chained [13]. "What should the farmer have done?" Is the question of the naive self. The guardian of the law is deceiving like Gurnemanz: “don't ask too many questions”. Yet by questioning Parsifal he would have been safe and savior.

But the irony of the guilt it is always in its being beatrix: Parsifal is cursed, but his name appears on the Grail cup because he is got back, went around the world to make up for his lack. The farmer does what the caretaker tells him: but at the point of death a question urges in his throat, which seems to make the light shine through the Door. The death of the knight on the threshold (as the Wild Knights Chesterton) [14] it is heroic, that of the farmer is not, but it is still a consummated death at the outset, and see the Light.

Josef K. is offended from history, he interprets it in a conflictual way, alternately contrasting points of view, without grasping the tertium that the priest-Talmudist tries to make him see with his sinuous ironies. Kafka wrote to Milena that we gladly make fun of the tenor of melodrama when she sings an interminable aria on the verge of death; yet, he says, we do exactly that - we lie on the ground and sing for years [15].

Consuming oneself in waiting in a non-heroic way, consuming oneself in waiting in a heroic way: moon and sun, dust and flame. The parody does not destroy the chivalrous tale, it confirms it by turning it upside down. Kafka was the knight of the absolute destructive and together of the irony that damn and save.

There is an essential discernment between "sense of guilt" and right perception of guilt: the first is a neurotic reproach that the ego addresses to itself to "feel at ease" with the internal censor, the second is a confused but firm knowledge, in which the guilty person grasps himself intertwined with the common destiny of humanity. The first is the prison wall, the second is the key to it. Indeed Markel, the rebellious and predestined brother of the starec Zosima, in Brothers karamazov, frees himself from the sense of guilt that sours him thanks to the purgatorial and celestial intuition of the solidarity of evil-suffering: "Everyone is guilty of everything in front of everyone" [16].

Borgesspeaking of Chesterton, he contrasts the Kafkaesque tale about the Door of the Law with that of Bunyan about the knight who asks the keeper of the castle to write his name on the register, because it will be he to enter [17] - clear midrash of the verse "The violent kidnap [the Kingdom of Heaven]" [18]. In fact the Wild Knights di Chesterton dies trying to enter, like Moses - and Kafka's farmer [19]. But to the violence a very different type of violence takes over, sub contrary species, under the mantle of one shameful passivity.

The similarities between the story of Parsifal and that of Ḥasīb Karīm al-dīn, in the One thousand and one nights [20]. In both cases the mother keeps the child away from the occupations of the dead father: Parsifal and Ḥasīb are two simple boys, fools. They will have to win wisdom by their efforts (Ḥasib, he-who-achieves: the divine decree goes achieved by human will) and both will know the phallus that pushes the return, the beatrix culpa. The Queen of the Serpents is a female Grail, serpentine wisdom found wandering in a cave: Is the kundalini.

Parsifal becomes a knight like his father, indeed, he surpasses his father: he is the king of the Grail, an initiate. Ḥasīb becomes a sage like his father, indeed, he surpasses his father: he is a sage who has eaten the flesh of the serpent, not a book eater. Eventually she will be able to approach the quintessence of paternal knowledge, the five pages that survived the shipwreck - and kept by her mother while waiting for her son to make them about her on the streets of his destiny, since he no longer needs it (so Abdelfattah Kilito) [21].

Note:

[1] First of all, as a key, the Titorelli-Titurel juxtaposition is imposed, cf. eg. The Poetics of Myth, by EM Meletinsky, 2014.

[2] The icon of the Pietà, of the Moon supporting the hidden Sun, with all its soteriological and Gnostic resonances.

[3] In Dzogchen it is said that the most advanced practitioners die "like an old dog", while the worst "like a king". The dead dog is also the Manichean (and Christian-Manichean) image of the world fallen into dark putrefaction, whose spiritual "teeth" however continue to manifest the beauty of the Pleroma of Light.

[4] «Death is the Messiah. This is the truth "(final of Moskat family).

[5] R. Steiner, Christ and the spirit world. The search for the Holy Grail, Ed. Antroposofica, Milan, 20133.

[6] Kafka was a passionate reader of Zhuangzi, as he especially confided to G. Janouch. W. Benjamin sees in Kafka's work "a force field between the Torah and the Tao" (GS, II, 3, p. 1212).

[7] The last words of the priest: «The court wants nothing from you. It welcomes you when you come and lets you go when you go "(tr. G. Zampa).

[8] In chapter X of the Trial, the two executioners are explicitly compared by Josef K. to "low-ranking actors", to "tenors", and the killing suggests, as often happens in the Kafkaesque opera, the ritual of sheḥitah, slaughter kosher.

[9] Ladislao Mittner recalls (in a note of his History of German literature): «Reading the first chapter of the Production, Kafka laughed to tears ».

[10] Unfinished chapter A dream, then inserted, as a story in its own right, in the collection A country doctor.

[11] The famous "ending" of the unfinished novel: «'Like a dog,' he said, it was as if shame had to survive him» (tr. Cit.).

[12] The moon is the "gate of heaven" and the vehicle of the dead who remain connected to the earthly destiny, i Manes, the fathers". The rattle of dying Josef K. will remain in the samsaric flow, his tragicomic existence and death are a vision for those who know how to see and a seed of rebirth for those who are entangled. See in this regard R. Giorgetti, The emanations of the "Dark Satellite", on AXIS mundi.

[13] End of the story Prometheus: «The inexplicable rocky mountain remained. - The legend tries to explain the inexplicable. Since it comes from a foundation of truth, it must again end in the inexplicable ».

[14] The poem gives its title to the first collection of verses by the English writer, published in 1900. The text is properly twofold: it consists of a short lyric monologue by the Knight and a dramatic poem that stages his death as a mad mystic: "I ride , / burning for ever in consuming fire ".

[15] Letter of September 1920.

[16] Brothers karamazov, p. II, book 6, chap. 1.

[17] About Chesterton (Other inquisitions). According to Borges, Chesterton sought throughout his life to write the heroic parable of the Pilgrim's Progress, but something in him always remained inclined to write the Kafkaesque parable of the peasant in front of the Gate of the Law.

[18] Returning to the Borgesian reflection: the contrast between being consumed violently in the flame and declining indefinitely in the dust of waiting is ancient - we find it in Cato (rusting or consuming oneself), in J. Conrad ("In life, understand, there is no great choice. Either rot or burn "), in Michelstaedter, in rock ... In the light of what has been said, let us ask ourselves, however, if the red vertical leap of the flame and the red leprosy of rust, if the instant unification and the slow disintegration of dust and ashes, are not different forms of Time, of his delay (or his impatience) essential with respect to the Eternal: Chesterton's swing (of Chesterton of Borges) is none other than the wisdom of contiunctio oppositorum. The hero who flares up, the martyr, without the delay indecorous of the peasant - and without the humor third of those who observe both scenes - risks not being, evangelically, "salted with fire" (Mc 9,49): not to have sale.

[19] Mt 11,12:XNUMX: "The kingdom of heaven suffers violence and the violent seize it". Even in the Talmud the wise-saints are those who "enter without asking permission".

[20] Nights 483-536.

[21] A. Kilito, The eye and the needle. Essay on the "Thousand and One Nights", The New Melangolo, Genoa, 1994.

A comment on "The apocalyptic humor of Josef K., the anti-Parsifal"