After the analysis of "The Sandman", the treatment of the second part of our essay on ETA Hoffmann focuses on other "Nocturnes" in which the previously anticipated 'disturbing' themes are treated, and also other more specifically 'demonic-witches' themes.

di Marco Maculotti

image: Mario Laboccetta, from “Tales of Hoffmann”, 1932

part II of II

Here our analysis of the stories continues disturbing di Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann. After having analyzed, with the help of the essays by Freud, Jentsch and Ligotti, "The Sandman" [1], we now turn to other Hoffmannian stories of the fantastic and the Weird (also contained in the double collection Night pieces ("Night tales") [2], published in 1816 and 1817) which stand out as some of the most innovative tales of "magic and sorcery" of modern literature. We will also analyze another story of ours that has many points in common with the "Nocturnes" analyzed here: Vampirism, released in 1821.

"THE DESERT HOUSE"

Ne "The deserted house" (Das ode Haus), for example, we find a variation on the theme of labile boundary that separates a real person from a automaton / puppet / simulacrum, one of the most recurring reasons of the disturbing, already recognized by Jentsch [3] and recently gutted by Thomas Ligotti [4]. The protagonist of this story, Theodore (Hoffmann's second first name, and therefore more than ever an alter-ego of his), suffers an unhealthy attraction for a building which, despite its excellent location in the city center of Berlin, appears abandoned and uninhabited for years. It is rumored that it is the property of an old countess who has long since left the city and has appointed an administrator, who visits it from time to time, to take care of the bureaucratic matters of the building. The situation precipitates when Theodore, observing the upper floor of the town one day, witnesses a human presence inside it, which however can be neither the old countess nor the equally elderly administrator: since he glimpses, peeping out from behind the curtain, what looks like the jeweled hand of a young and healthy woman, certainly not that of some elderly tenant. Now entangled in the mystery, the young man will spend his days walking back and forth along the street, waiting for the mysterious lady to appear again.

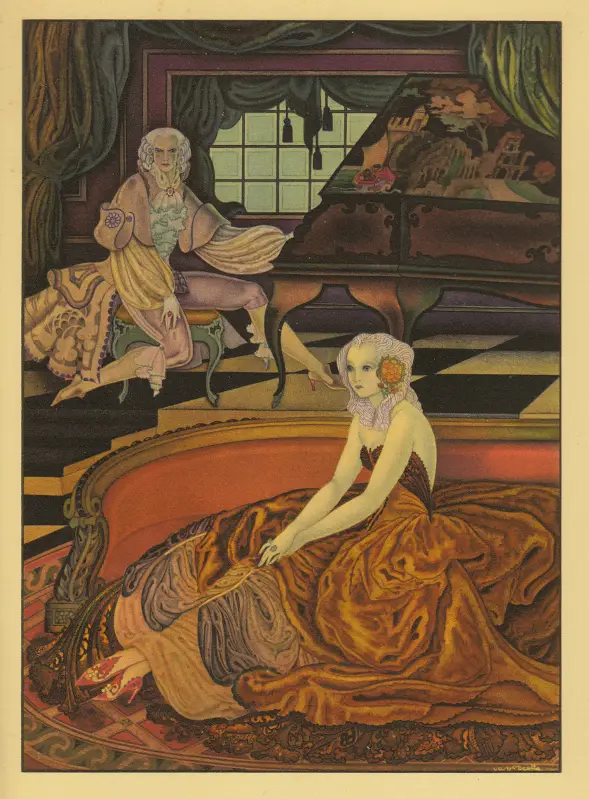

To be able to spy on her better, without arousing suspicion, he gets to buy one hand mirror from a street vendor Italian taste (like the optician and street vendor of barometers Coppola in "The Man of the Sand", who specularly sells the telescope to the protagonist with which to observe Olimpia). When the woman suddenly looks out the window, he falls into ecstasy, yet there is something wrong: there is something unheimlich. First of all, after staring at her for some time, he realizes her inanimate expression, exactly like that of Olympia in Der sandmann. As if this were not enough, some passers-by intrigued by his maneuvers with the mirror and by his singular facial expressions let him know that no young woman lives in that house: what he saw when mistaking for the attractive lady is without a shadow of a doubt a framework. Here the mirror reveals a double function: one, it has been said, mirroring that of the telescope of "The Man of the Sand", namely to act as a medium for to see better something that one has difficulty seeing, to fully understand what «it should have remained secret, hidden, and instead surfaced " (Schelling). The other, which recalls the role of mirrors in another "Notturno" ("New Year's Eve"), has to do with witchcraft and magic aphroditic: the mirror like portal to the Elsewhere, which not only allows the protagonist to see with his eyes (what not should see), but which also catapults him into a supernatural situation that threatens to fatally undermine his sanity. The mysterious lady, in fact, begins to appear in the mirror every time the young man, after invoking her love for her, breathes on it.

Only in the finale will it be discovered that the view e the imagination they betrayed Theodore; the oleographic simulacrum of the charming lady was actually a 'magical creation' of Angelica, Countess Gabriella's elder sister: the image reflected in the mirror and at the window was 'projected' by the old woman on the likeness of Edmonda, the young daughter of Gabriella. Angelica, for her part, far from appearing as a young and attractive woman, finally reveals herself as an old hag, whom the protagonist will discover living in the deserted house, looked after by the administrator, under the order of her sister, after she lost her sanity when, many years earlier, her betrothed fell in love with her younger sister (Gabriella, in fact), abandoning her just before the wedding. Suddenly leaving her paternal home, the derelict went to live for a period with a caravan of gypsies: Hoffmann suggests that through them, devoured by an implacable desire for revenge, the woman has learned the supernatural arts, obviously including that of 'binding her victims to oneself', with the art of magic and illusion. The appearance under which he appears in the eyes of the "lover" Theodore are - as mentioned - those of his sister's daughter, the virginal Edmonda, who the protagonist will see enter the scene only in the final stages, being understandably shocked at the appearance of her. Before long there had also been space, ça va sans dire, for revenge against her sister: with aphroditic magic Angelica had managed to attract her husband, who was later found lifeless due, according to the doctors, to a nervous apoplexy. It was after this drama that Angelica was removed from her paternal home in Pisa and 'sent' to Berlin, from whose 'deserted house' the witch continued to practice the magical arts.

"NEW YEAR'S EVE"

In many ways similar to "The deserted house", too "New Year's Eve" (Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht) focuses on the theme of fatal woman devoted to diabolical practices and the production of 'love potions', a sort of modern Circe sorceress named Giulia. In this tale, the unfortunates who have fallen into the canvas fatal of the witch and her accomplice, Mr. Everywhere (another character mephistophelic comparable to Coppelius / Coppola from "The Sandman") there are even three, one of which has been stolenshadow, and another thereflected image. Naturally, both the loss of the shadow and that of the reflected image are equivalent, in a psychoanalytic sense, to an irreparable disintegration of the personality. The three unfortunates, who met by pure coincidence in a disused tavern on New Year's Eve, complain to each other about their respective bitter love affairs, until they realize that all three of them have been deceived by the same woman.

Here too the leitmotif the mirror, who with the function of portal to the Elsewhere as well as of receptacle of the ritual practices of the sorceress. To the actual narrator-protagonist, Erasmus, there are two other peculiar, contradictory characters, disturbing and complementary; one of them, by virtue of some devilry hatched by Giulia and Mr. Dappertutto, even gives the impression of changing face from moment to moment, appearing now young, now old: is the apocalyptic carnival of Hoffmannian poetics whose thousand masks reflect and recall each other, as in a kaleidoscopic game - precisely - of mirrors.

It is curious to note how in Hoffmann's "Nocturnes" the 'fatal' and 'diabolical' women, engaged in magical and witch-like practices ranging from the 'power of illusion' to magic aphroditic, are systematically of Italian origin, or at least resident in Italy for a certain period of time: in addition to Giulia, also Olimpia in “The Sandman” and the couple Angela / Antonia in “Il Consiglioere Crespel”; and the examples can be extended almost indefinitely by examining the entire literary production of German. That Hoffmann, who during his natural life made countless journeys in our peninsula, was aware of the diffusion, even in a recent epoch, of forbidden and witch-like practices in the Italian districts, and especially in the villages of Tuscany, which he so often mentioned in his literary creations? Yet it was only after many decades, precisely in 1899, that such atavistic and apparently forgotten practices were brought to the attention of the educated public, with Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches by Charles Godfrey Leland [5].

"THE VOTE"

Even more paradigmatic as regards the fusion of perturbing suggestions winking at tradition satanic-witchy with equally disturbing elements concerning, more prosaically, psycho-physical health is "The vote" (Das Gelübde). The central character of this story is one of the most successful figures of Hoffmann's literary universe: she is presented to us in media res, like an "old lady", wrapped in suffocating veli dark than that mask identity. We know from the beginning of the story that she is in a state of expectation, an element that obviously clashes with the presentation of the woman given to the reader in the first place. Here too, as in all the other "Nocturnes", nothing is as it appears, appearance and illusion being, as we have seen, closely connected in Hoffmann's poetics. More, also in this case theunheimlich hatches its harmful poisons in the family home, in the heart of theHeimlich.

Here, too, ours uses artifice disturbing of the puppet: ultimately you will find that the enigmatic veiled woman, Ermenegilda / Celestina, wears a white mask, expressionless, extremely close to the face; Hoffmann will let the reader understand that the woman is forced to hide her true face, irreparably and monstrously marked by an infamous pact with the Devil (also of the natural father of her son, brother of her husband who died in the war, it is emphasized that the face is , after the conclusion of the nefarious facts narrated, "disfigured by the furrows of profound suffering"). In the finale he alludes to the fact that the child born from the sacrilegious union between Ermenegilda and Saverio, brother of the woman's husband, he should be "Consecrated to the Church" ... but of as Church do you speak? If, as it is legitimate to think, it is the "coven" of the Carmelite confessor Cyprian - who blesses Ermenegilda, baptizing her with a new name (like the Initiates) before she leaves her native country -, nothing prevents us from believing that the newborn is state consecrated to the Devil. Saverio will also try to free him from the clutches of the sect by kidnapping him: however, as soon as he has led him elsewhere, the child dies instantly, for no apparent reason - an indubitable sign of his belonging to a world. other from which it has been unduly stolen.

Here too, the theme of doppelganger. In addition to the protagonist Ermenegilda / Celestina, who appears functionally in the role of two classic female archetypal figures (the devoted virgin mother and the vengeful witch), even the two male figures who love women, namely the two brothers Stanislao and Saverio, are in effect one the 'double' of the other. Paradigmatic are above all the scenes in which Saverio tries to approach the unfortunate widow of her brother by narrating the latter's exploits in battle:

"He spoke only of Stanislao, of his infinite love for his sweet bride, but through the flames he aroused he was able to skilfully make his own image glimpse, so that Ermenegilda confused and stunned did not even know how to keep the two images separate, that of Stanislaus absent and that of Saverio present. »

It could be said that even the descendant born of the woman is potentially both of one brother and of the other, since Ermenegilda is indeed possessed by Xavier, but in the midst of a mystical ecstasy during which, 'in spirit ', she meets her husband Stanislao, now ready to sacrifice himself for his beloved homeland under enemy fire.

"THE VAMPIRISM"

We have already noted in the previous article [7] as, in the tales ofHoffman:

«… The“ uncanny ”is often connected to a dimension that can be well defined familiar, domestic: the abhorred delusional mysteries encountered by the protagonists of his stories (to a certain extent the author's alter-ego) have more often than not to do with family dramas, tragic situations that, precisely by virtue of their being Heimlich (i.e. domestic, private, intimate) they end up becoming necessarily, when you insert a foreign element (usually the protagonist or narrator) unheimlich: it is therefore necessary to keep them hidden as much as possible, to hide them away from prying eyes. He will be the protagonist on time Hoffmannian to "put his beak into it", as they say, attracting to him malevolent influences that he would have done better not to investigate - a theme that will then typically become Lovecraftian. And, in this regard, the observation of the Schelling: "unheimlich it is all that should have remained secret, hidden, and instead surfaced. »

In this sense it is paradigmatic "Vampirism"(Vampiresmus. Eine gräßliche Geschichte, short story, also known in Italian as “Le Iene”, inserted in the fourth volume of the collection The Brothers of Serapion released in 1821), in which the wealthy protagonist, Count Ippolito, falls in love with the sweet Aurelia: the only disturbing side of a relationship that could otherwise be idyllic is represented by the girl's mother, a hag about whom terrifying things are rumored : we are here in front of a recurring dichotomy in Hoffmann's stories, that between the feral girl and the abominable witch. When the harpy suddenly dies, on their wedding day, fate seems to smile at them. Yet the feeling of unheimlich it does not vanish at all, far from it: the suave Aurelia wastes away and gives more and more worrying signs of psycho-physical failure.

Only when, putting aside the compassion and blind trust in the woman with whom he shares the nuptial bed, does Count Ippolito begin to take seriously the rumors circulating about the deceased mother, will he be able to connect the dots and see things as they really are: his wife is, genetically speaking, a damned, offspring of a stump entangled with witch and demonic magic. Particularly powerful and 'cinematic', although extremely short, it is the only truly horrifying scene in the story; the one in which Ippolito, woke up in the night and not finding his wife in bed, goes out into the park of the estate and reaches the cemetery, where he surprises Aurelia in a shocking attitude:

'The door to the cemetery was open; he entered, and in the full moonlight, a few paces from him, he saw a group of hideous ghostly figures: half-naked old women with matted hair, crouched on the ground around a man's corpse which they devoured with belligerent greed. Among those hags there was also Aurelia! "

And yet - ironically - not even having it unmasked and knocked down allows the protagonist to escape from the nightmare: he, bitten in the chest by the demoness in the excited tet-à-tet conclusive, invariably plunges into the abyss of madness [8], as if dragged by the net (the wyrd of weird) woven by the demonic-feminine element represented by the person most dear to him in the whole world. Here's how theunheimlich irremediably emanates from what is (or, at least, it should be) Heimlich par excellence.

Note:

[1] See MACULOTTI, Marco: Eyes, puppets and doppelgänger: the "uncanny" in "Der Sandmann" by ETA Hoffmann (I); on AXIS mundi

[2] HOFFMANN, ETA: The man of the sand and other tales; Rizzoli, Milan 1950

[3] JENTSCH, Ernst: On the psychology of the uncanny; 1906

[4] LIGOTTI, Thomas: The conspiracy against the human race; the Assayer, Milan 2016

[5] GODFREY LELAND, Charles: Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches; 1899 (ed. It .: The songs of Aradia. The Gospel of the Italian Witches; Aradia Editions, Rende 2005)

[6] HOFFMANN, ETA: Vampirism; il Melangolo, Genoa 1981

[7] MACULOTTI, op. cit.

[8] "The count went mad": this is the final lapidary of the story

14 comments on “Reality, illusion, magic and witchcraft: the "uncanny" in ETA Hoffmann's "Nocturnes" (II)"