Today, 150 years ago, Algernon Blackwood was born, initiator of the narrative genre of "occult detectives" but above all unsurpassed cantor of the psychogeographic poetics of otherness.

di Marco Maculotti

«[…] The“ sadness ”that we attribute to a particular landscape is really and objectively in the landscape and not only in ourselves; consequently, the landscape can influence and plagiarize us, in exactly the same way that drugs, meat and alcohol produce their different effects in us. Poe, who knew many secrets, also knew this, and he taught us that studying the layout of gardens is really an equally noble art as poetry and painting, as it helps to express the mysteries of the human spirit. "

- Arthur Machen, The children of the pool (1936)

Already HP Lovecraft he applauded, in his own Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927), to the pervasive perception, emerging from the stories of Algernon Blackwood (1869 - 1951), of "An unreal world that continually looms over ours" [Horror theory, Bietti, Milan 2012, pp. 414-415]:

"No one else has even come close to the mastery, the seriousness, and the realistic and minute fidelity with which he notes the most mysterious aspects of everyday things and experiences, or the almost superhuman intuition with which he accumulates, particular upon particular, the complex sensations and perceptions that flow from reality into supernatural lives or visions […]. Best of all, he understands how much certain sensitive minds linger forever on the edge of the dream, and how relatively tenuous is the distinction between images produced by real objects and those resulting from the game of the imagination ».

We therefore find ourselves, with Blackwood's work, in the field of the so-called "Psychogeography", and will be of a very different mold from that, for example, of a Arthur Machen. If in the disturbing tales of the Welsh, in fact, the element psychogeographic of the environment appears indissolubly connected to the mythical-cultural and folkloric-cultural aspects of the populations that have been threatened there for millennia (in particular in Machen the populations of pre-Celtic and pre-Roman Gaelic lineage, connected to the "Little People"), in Blackwood the situation presents itself differently: in his tales of terror the geographical area becomes a portal of forces other and threatening completely divorced from the world of humanity, which prefer certain places as their own space of manifestation precisely by virtue of their desolation and their savage aspect, precisely because - in other words - they have not yet been trampled by the "civilizing" and "ordering" imprint of the human ecumene.

Central to Blackwood's work is therefore the atmosphere: an atmosphere suspended, in which the "modern man" seems to return ideally and traumatically, even for one night only, to the dawn of time. Suddenly found himself surrounded by virgin nature, we might say pre-human, only then does the Blackwoodian protagonist feel the instability and fragility of the position that the "civilized" human being holds within a cosmos which, in the final analysis, appears as the stage on which they manifest themselves atavistic powers far older than humanity and not conceivable according to the social and moral values proper to it; powers which, although sometimes manifesting themselves by means of the natural elements known to us, nevertheless differ ontologically from them, using them rather as portals to manifest themselves in our reality, which they access by infiltrating through the fleeting veil that separates it from the "other world".

There are above all two stories, within the author's literary production, that we bring as an example of this particular of his psychogeographic poetics of alterality (“Il Wendigo” and “I salici”) with the addition of a third (“Lupo-che-corre”) which, while presenting thematic differences, in other ways adds interesting nuances to the topic treated here.

"THE WENDIGO"

"Il Wendigo" (1910), inspired by an Algonquian folk tradition (an ethnic group that includes Cree, Ojibwa, Abenaki, Blackfoot, Mik'maq and many other minor groups) with which the European settlers came into contact sinceeighteenth-century era of the trapper and logger, It is probably Blackwood's best known tale; accessible to Italian readers thanks to its inclusion, by Gianni Pilo, in the Fanucci register of the cycle "The myths of Cthulhu" entitled The Cthulhu saga (Rome 1986). The mythical character of the Wendigo will later be inserted, starting with August Darleth, in some stories belonging to the "cycle of the Great Ancients" with the name of Ithaqua, demon of the northerly winds. [We have already had the opportunity, on our pages, to talk about the corpus legendary-folkloric concerning the Wendigo: in this regard we refer the Readers to previous article by the writer and from that of Mollar, as well as the essay by Emanuela Monaco Manitu and Windigo: vision and anthropophagy among the Algonquians (Bulzoni, 1990)].

In Blackwood's story inspired by this native legend, a hunting expedition in the forests of the Canadian taiga, in the Ontario region, turns into a real nightmare: immediately the spaces appear immense to the protagonists ("They have no end, no, no have an end ... This many have discovered it, and they ended up badly! "), and it seems to them that"another one life "pulsates menacingly around them, in the atmosphere. From the beginning Défago, the French-Canadian guide with knowledge of indigenous legends, unconsciously tries to make the unfortunate protagonist Simpson, a young theologian, foretell what awaits them in those desolate endless lands, hinting at him "Men struck by a mysterious passion for wild nature, a real fever that the fascination of the deserted lands ignited in them and that, bewitching them, led them to death".

It is during the first night spent in a tent in the territory that the myth tells of being the geographical area of manifestation of the Wendigo that Défago shows the first worrying signs of letting up: suddenly, in the middle of a troubled dream, he lets himself go in an uncontrolled way to sobs and cries that are nothing short of impressive, which literally terrify Simpson, his tentmate:

«And his immediate impulse, before he could think or reflect, was a movement of intense tenderness. This intimate, human sound, heard in the desolation by which they were surrounded, aroused emotion. It was so absurd, so pitifully absurd ... and so vain! Tears… in those wild and cruel places: what were they for? "

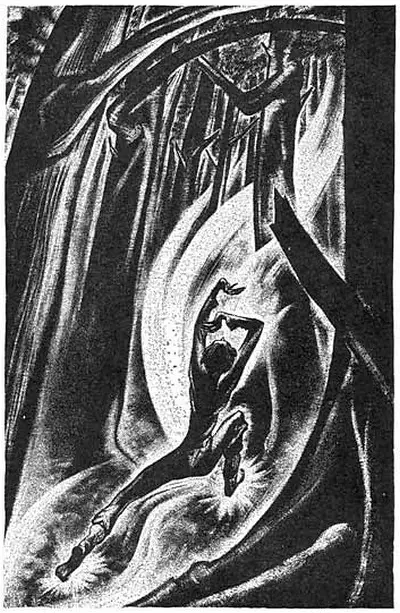

Since this moment, the «Totamente Other», epiphany of mysterium tremendous that is hidden behind the folds of reality, creeps into Simpson's rational mind. The horror continues when the latter notices that the body of his tent companion has been progressively dragged outside of it, so that the feet end up coming out of it, exposed to the cold winds of the subarctic night.

Then, here "the profound silence of dawn was broken by a very strange sound", which "came suddenly, without warning; and it was unspeakably frightening ": it was a" perhaps human "voice," hoarse and yet feeble ", coming" from outside the tent, but from close by; and rather from above than from the ground "; "A kind of windy, weeping voice, like something lonely and wild, horribly powerful", who calls the unfortunate guide by name: "Dé-fa-go!". Furthermore, a never-before-felt smell spreads throughout the scene, to say the least pungent and nauseating, which intoxicates Simpson like a malevolent spell.

The terror felt by the latter during the sinister night culminates at dawn, with the sudden abandonment of the tent by Défago, as if recalled by an insurmountable power:

"And as he left - with such astonishing rapidity that in an instant his voice could be heard dying in the distance - he screamed in a tone of maddened anguish, which at the same time had a strange note of frenzied exultation:"Oh! Oh! My feet on fire! My feet burning on fire! Oh! Oh! What impetus, what speed!""

Simpson can do no more, for the moment, than to warn the whole thing "The touch of a great Outer Horror", indecipherable according to the interpretative paradigms of civilized man, to whose mental universe he has always belonged, even though he is now, alone and defenseless, in the lonely and wild subarctic lands in the face of the Great Unknown. Left to himself, there is nothing left for him to do but try to find his adventure companion, following the traces left on the snow.

And here to the previous horror are added even more clues disturbing: the footsteps of Défago are accompanied by those of a large mysterious animal, "Sinister marks [...] left in the snow by the unknown creature who had lured a human being to bring him to ruin". Continuing the 'track', the skeletal footprints left by the inconceivable entity do not cease to upset the psyche of the pursuer: he realizes that, as the footprints move away, the distance between them increases significantly, almost as if the creature had stopped running for blow up with prodigious leaps of many meters. But - even more absurd - the same seems to have also occurred with regard to the footprints of his friend Défago, who left the tent at dawn as if recalled by an atavistic and ungovernable instinct!

“And the sight of these weird tracks running side by side, silent evidence of a journey in which terror or madness had led to impossible results, was deeply unsettling. He was troubled by it down to the secret depths of the soul. "

That's not all: at a certain point - Simpson realizes - the footprints of both the mysterious creature and the French-Canadian guide suddenly stop, as if the two had literally left the ground:

“At that moment it seemed to him that he was having the most destructive experience of his life; his heart emptied of any sensation, as if it had suddenly dried up. "Oh! This terrible height! Oh, my feet on fire! My feet burning on fire!". This anguished call ran from heaven with vague and pleading hints. "

Hearing for the second time the call of the one who had been possessed by the Wendigo, at the height of the terror, Simpson starts running frantically towards the tent,

“Because in that distant voice, it was the Panic of the Wilderness - the Power of Immense Distance - the Charm of Desolation leading to death that called him. At that moment he knew all the sufferings of those who have been irremediably lost, with no hope of finding their way back; the pains of the soul that experiences the pleasure and pain of Infinite Solitude. The vision of Défago, eternally pursued, hunted, pushed through the lofty vastness of those ancient forests, shone like a flame among the dark ruins of his thoughts. »

Only when he manages to reunite with the other members of the expedition, Simpson begins to evaluate the inexplicable facts he has witnessed according to the traditions of the natives of the place. Speaking with Dr. Cathcart and Hank, he learns that Défago did not want to go hunting in that region because of the rumors of many Indians who had "seen the Wendigo" there ("When an Indian goes crazy they always find out that he has" seen the Wendigo ""), "The personification of the Voice of the Wind, of which some natures feel the call to the point of being led to death":

« The Voice, they say, resembles all the sounds of the forest: to the wind, to flowing water, to the cries of animals, and so on. And when the victim la hear, it is already lost, of course! "

The tremendous experience of the Wendigo therefore presents itself, in the Algonquian tradition as in the story under analysis here, as a real panic catharsis, characteristic of those Eskimo-Amerindian populations of the far north who, spending the very long winters in the desolate vastness of the taiga, are particularly subject to what the psychoanalysis of the twentieth century called arctic hysteria. Nonetheless, the more chilling details of the native folklore beliefs about the Wendigo have yet to be revealed by the two interlocutors to an increasingly terrified Simpson:

“His most vulnerable spots are said to be his feet and eyes; the feet, you understand, for the desire to go, and the eyes for the desire for beauty. The poor man ["kidnapped" by the Wendigo, ed] goes at such a terrible speed that the eyes bleed, and the feet burn. […] The Wendigo is said to burn its feet - evidently from the friction produced by his tremendous speed, until they fall. And then new feet are reformed exactly the same as the previous ones. [...] And it doesn't always stay on the ground, but sometimes it gets so high that you think the stars have set it on fire. And he makes great leaps, and runs along the top of the trees, dragging his companion with him, only to drop it as the sea eagle drops a small pike to kill it before eating it. And the food of it, of all the garbage of the forest is… the moss! "

And it is at this point, at the height of the nervous tension, that finally Simpson's two interlocutors also hear the call of the Wendigo for the first time, that their companion in adventure had already had the opportunity to hear twice: the words they are exactly the same, and horribly appeal to all bewilders topos of the native legends about the malevolent entity of the winter taiga: thefrightening height, insane speed and feet that burn with fire. And here, as soon as they hear this gruesome call from above, the three friends hear falling down from the sky, with a frightening thud on the frozen ground, what seems to be the body of the revived Défago, who addresses them with a feeble voice. and hoarse, panting and gasping: «I'm having a nice ride in hell ...».

The repellent aspect of Défago, quite similar to a parody or "ghostly caricature" of what had once been, deeply baffles his three expedition companions; but the supreme horror comes when, moving in such a way as to expose his legs to the light of the hearth, they notice for the first time his monstrous feet, burned by the mad rush in the vastness of the northern sky. It is the last, horrendous, epiphany: then "Défago" - or whatever it has become - he returns with astonishing rapidity to his own appalling heights, to travel the cosmic immensities in the company of the demon who possesses it.

Later, returning to base camp, the three friends find the true Défago: this time it's really him, and there is no longer any trace of demonic possession. Yet he now presents himself with a stupid expression, as if he had been completely emptied of all human personality, like a puppet now devoid of all will and vital spirit, a kind of vegetable that manages to eat only moss and who can do nothing but complain about his own sore feet. Simpson's notes conclude in an exemplary way the disturbing story, beautifully narrated by Blackwood:

“It was his opinion that there, in the heart of the wilderness, they had witnessed something cruelly primitive. Something that had survived, somehow, the advance of humanity, and now had made its terrible appearance, revealing the existence of a primordial and monstrous dimension of life. Simpson considered that experience as a look at the prehistoric ages, when the heart of man was still oppressed by huge and savage superstitions; when the forces of nature were still intact, and the Powers that must have dominated the primitive universe were not yet defeated. He still today he thinks back to what, years later, he defined in a sermon "Formidable and savage powers that lurk in the souls of men, not evil in themselves, but fundamentally hostile to humanity as it is ”. "

"THE WILLOWS"

The same themes that emerge from the reading of "The Wendigo" were dealt with by Blackwood in a story written in 1907, The willows ("The willows"), deeply influenced by the travels made by the author on the Danube and considered by Lovecraft his creative peak as well as the best British story ever ascribable to the genre of Supernatural Horror [the story can be consulted by Italian readers in the anthology HP Lovecraft - My favorite horrors, edited by Gianni Pilo and Sebastiano Fusco, Newton Compton, Rome 1994)].

Compared to "Il Wendigo" we find ourselves in the lands ofEastern Europe instead of those of North America, but the substance does not change. The narrative centers on the expedition of two friends to a vast marshy area, which Hungarian locals superstitiously avoid, as they believe they belong "to beings foreign to the world of men":

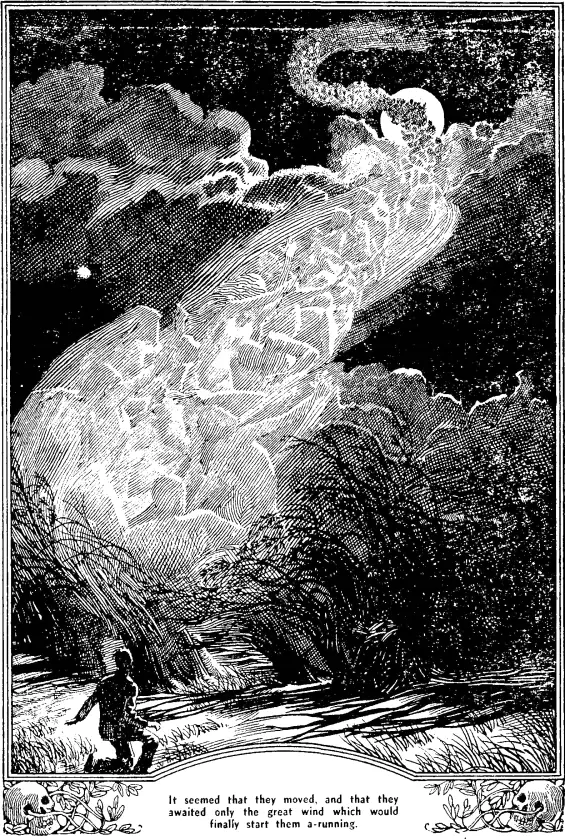

«The dismal charm of that lonely island that emerged among millions of willows, swept by a hurricane and surrounded by deep swirling waters […]. Never trampled by a human foot, and almost unknown, it lay there, under the moon, far from human influences, on the frontier of another world: an alien world, inhabited only by willows and willow souls »

Although manifesting themselves to the senses of the protagonists through the physicality of the willows, the more one continues in the reading, the more it becomes clear that the malevolent entities that threaten them limit themselves to using these plants as "masks" to access our world: “It's the willows, of course. The willows mask "the others", but the others are looking for us around here ".

It should be immediately noted that here too, in the same way as the story previously analyzed, Blackwood stages the feeling of total otherness that possesses the "civilized" man as soon as he moves away from his own safe-zone urban, fatally plunges into primordial nature, where the "formidable and savage Powers" still survive which, penetrating threateningly into the human soul, can only lead to death or madness.

Thus, since the first night spent in the vastness of the "alien island", the willows seem to be possessed by a sinister and supernatural will, the bushes seem to move, a remote vibration similar to the sound of a gong seems to spread throughout the area, coming from now from above, now from below, and even da in the protagonists themselves ("in the way a sound is said to come from the Fourth Dimension").

“It is the sound of their world, the echo of their kingdom. The diaphragm here is so thin that somehow there is a transition between the two regions, and the sound can filter through. But, if you listen closely, you will find that it is not so much above it as it is around us. It is in the willows. It is the willows themselves that echo him, because here the willows have become symbols of the forces that are hostile to us. »

Also in this tale the supernatural powers, hostile to man, do not appear evil in themselves, but rather totally alien, other with respect to the typical morality of the human being: it is about chaotic forces, ontologically in dichotomous contrast with the intellect ascribable to Logos "Ordinator" who governs human rationality. "There are things around us - exclaims one of the two adventurers - that aim at disorder, disintegration, destruction ... the our destruction".

In the darkness of the night, surrounded by vibrational sound beams that seem to try to locate them and increasingly pervaded by dark omens, the two experience a "dark ancestral sense of terror, more deeply disturbing than anything else "they ever lived or dreamed". Blackwood's mastery, perhaps in The willows even more than in Wendigo, lies precisely in being able to bring the Reader into an atmosphere that is so full of atavistic terror, avoiding to define in actual terms in what it concretely expresses itself.

In fact, while focusing the narration on the sinister feeling, felt by the two protagonists, of being in "A place occupied by inhabitants of a different space, a kind of outpost from which they could spy on the Earth, remaining invisible, a point where the veil that divided us had become thinner", Blackwood does not explicitly define who o thing be these inhabitants of a different space: one of the two narrators considers them "a personification of the disturbing elements", while the other has the impression of having profaned an ancient sanctuary, "A place where ancestral deities still had their domain, where the emotional forces of the ancient worshipers still hovered".

It is at this point in the narrative that reality appears completely transfigured in the eyes of the narrator, and here is the "other world" erupting in all its shining, terrifying otherness, in the extraordinary psychogeographic horror of Blackwood style, whose imaginative genius in certain passages even seems to anticipate the"Pataphysical hypothesis" by Keel and Vallée, several decades later:

«Never, before or since, have I been attacked with such force by indescribable suggestions of a "further region", of another pattern of life, another evolution not parallel to the human one. And, in the end, our minds would have to succumb under the weight of that frightening spell, and we would have been drawn across the border into their world. […] All these elements, had been robbed of their natural characters, and had revealed something of a other their appearance: what prevailed across the border, in the other region. And this distorted aspect, I felt, was foreign not only to me, but to the entire human race. The whole experience whose limits we were touching was completely unknown to humanity. It was another sphere of experience, "not earthly" in the truest sense of the word. "

Further on, one of the two protagonists describes the nature of these mysterious entities in tones that, in addition to anticipating them by twenty years suggestions Lovecraftian cosmics, could elevate Blackwood to an involuntary precursor of a vast line of Fortian research and literature, from the theories of Salvador Freixedo to more or less New Age of the theosophical myth of the "King of the World" of Ossendowski and Guenonian memory:

“We happened to camp at a point where their region touches ours, where the veil between the two has become thinner. [...] All my life I have been strangely, keenly aware of the existence of another kingdom, not very distant from our world, in a sense, but of a quite different nature., where great things happen continually, where immense and terrible personalities are busy, busy in enormous enterprises, in comparison with which earthly affairs, the rise and fall of nations, the destinies of empires, the fate of armies and continents, are like dust […]. You think they are the spirits of the elements, and I thought maybe they were the ancient gods. But now I tell you that it is neither of the one nor of the other. These would be understandable entities, because they have relationships with men, they depend on them for worship and sacrifices: while these beings who are now around us have absolutely nothing to do with humanity, and it is a simple combination that their space touches ours, right at this point »

"RUNNING WOLF"

Partially attributable to this Blackwoodian strand of the "Panic Horror of the Wild Nature" and of the "Infinite Solitude" is also a third story, Running Wolf ("Lupo-che-corre"), published for the first time in 1920 and available in the Italian translation in the collection of short stories by various authors Full moon nights, published by Fanucci (Rome 1987) within the series “The myths of Cthulhu”, edited by Domenico Cammarota.

Here, the protagonist is Malcolm Hyde, a fisherman who, despite the advice of the locals, ventures to camp on the "forbidden" bank of the Medicine Lake, where the natives once used to perform their own shamanic rituals. In this story there is a sort of psychological explanation for this disturbing and panic sensation, already encountered in the two stories analyzed above, a sensation that emerges from suddenly finding oneself in the most absolute solitude, in the midst of Wilderness boundless:

« A man who is in similar conditions and in a similar place does not feel the discomfort until the sense of loneliness strikes him as something too real and vivid. Loneliness brings charm, pleasure, and a nice feeling of calm until, or unless, it gets too close. It should remain only one ingredient among others; it shouldn't be noticed too directly, too concretely. Once she gets too close, though, she can easily cross the narrow line between well-being and malaise, and darkness is the worst time for this transition. "

For Malcolm Hyde, this transition occurs when, as soon as darkness falls, he realizes with terror that he is being watched by someone or from qualcosa which, although it cannot see, seems to hide within - once again - a group of thickets willows.

Why - allow us a brief excursus –, among all the plants, the willows? Blackwood probably wasn't fasting British folklore, where this plant is closely connected with the magical and witchcraft practices. For the Britons, testify Robert Graves, the willow is in fact traditionally and even before semantically linked to witches: the terms witch e willow they derive from the same root, just as they also derive from the same root wicked ("Wicked") e wicker ("Wicker"), namely the branch of Salix viminalis, used by the Celts for the realization of the puppet in the famous sacrificial practice of Wicker Man, already reported by Julius Caesar in De Bello Gallico (note how in The willows the two protagonists feel very clearly that they have been chosen as sacrificial victims from the "Willows"). Not only that: the North Berwick witches claimed to fly to the Sabbaths on grain sieves intertwined with willow; the famous broom of the English witches was tied with willow; according to a popular belief with two willow branches intertwined in the shape of a cross one could predict one's death; and so on.

Furthermore, perhaps even more explanatory tradition here, in Greek mythology the willow is the tree placed at the gates of the Underworld, in that transitional territory between earth and water, between the "world above" and the "world below". For this reason it was considered by the Mediterranean populations to be sacred to Hecate, the selenic goddess of the night, of the dead and of magic. Willows grow in the inferior grove of Persephone, and Orpheus in the myth tries to bring Eurydice back to the world of the living by holding a willow branch in his hand.

Nonetheless - returning to Running Wolf and moving towards the conclusion - unlike Wendigo e willows, here supernatural power is not wholly foreign to the world of men and his morality, indeed. In fact, he turns out to be the disembodied and penitent soul of a powerful native shaman, guilty of having committed a ritual sin in his life and therefore expelled from his tribe and left to die without burial. A member of the Wolf clan, he had - unforgivable sacrilege - killed a specimen of theanimal-totem of the tribal group and for this reason, after his physical death, he continued to wander on the "forbidden" shore of Medicine Lake in the guise of a wolf, until someone gave him a pious burial. Hyde, guided by the animal, conducts operations in an exemplary manner, thus freeing the damned soul from him wandering about him that, had he not met him, he could have been eternal.

Bibliography:

- BLACKWOOD, Algernon: Wolf-running. Contained in Full Moon Nights. Edited by D. Cammarota, series "The myths of Cthulhu", Fanucci, Rome 1987

- BLACKWOOD, Algernon: The willows. Contained in HP Lovecraft - My favorite horrors. Edited by G. Pilo and S. Fusco, Newton Compton, Rome 1994

- BLACKWOOD, Algernon: The Wendigo. Contained in The Cthulhu saga. Edited by G. Pilo, Fanucci, Rome 1986

- GRAVES, Robert: The white goddess. Adelphi, Milan

- LOVECRAFT, Howard Phillips: Horror Theory. All critical writings. Curated by G. De Turris, Bietti, Milan 2011

- MACULOTTI, Marco: Psychosis in the shamanic vision of the Algonquians: The Windigo, on AXIS mundi

- MOLLAR, Gian Mario: Jack Fiddler, Wendigo's last hunter, on AXIS mundi

- MOLLAR, Gian Mario: The mysteries of the Far West. Unusual, macabre and curious stories from the American frontier ". The Meeting Point, Vicenza 2019

- MONACO, Emanuela: Manitu and Windigo. Vision and anthropophagy among the Algonquians. Bulzoni, Rome 1990

I adore. Read John Silence recently