Recently translated into Italian by the types of Il Palindromo, "In praise of the Fantastic" by the French writer and journalist Jacques Bergier, best known for having written with Louis Pauwels "The morning of the wizards", provides an analysis of the work of some "magic writers" at the time unknown to the French-speaking public (including Tolkien, Machen and Stanislav Lem), aimed at defining a new paradigm for the XNUMXst century that can combine science and science fiction with the ontological category of the "sacred".

di Marco Maculotti

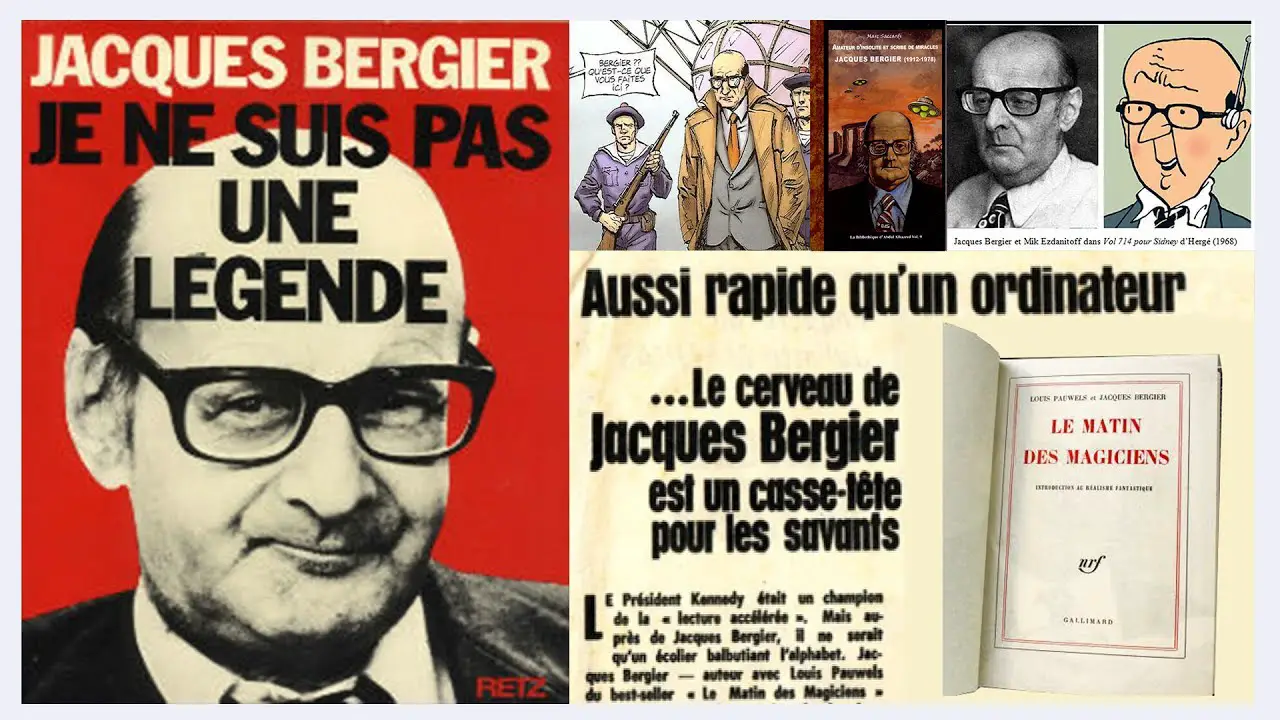

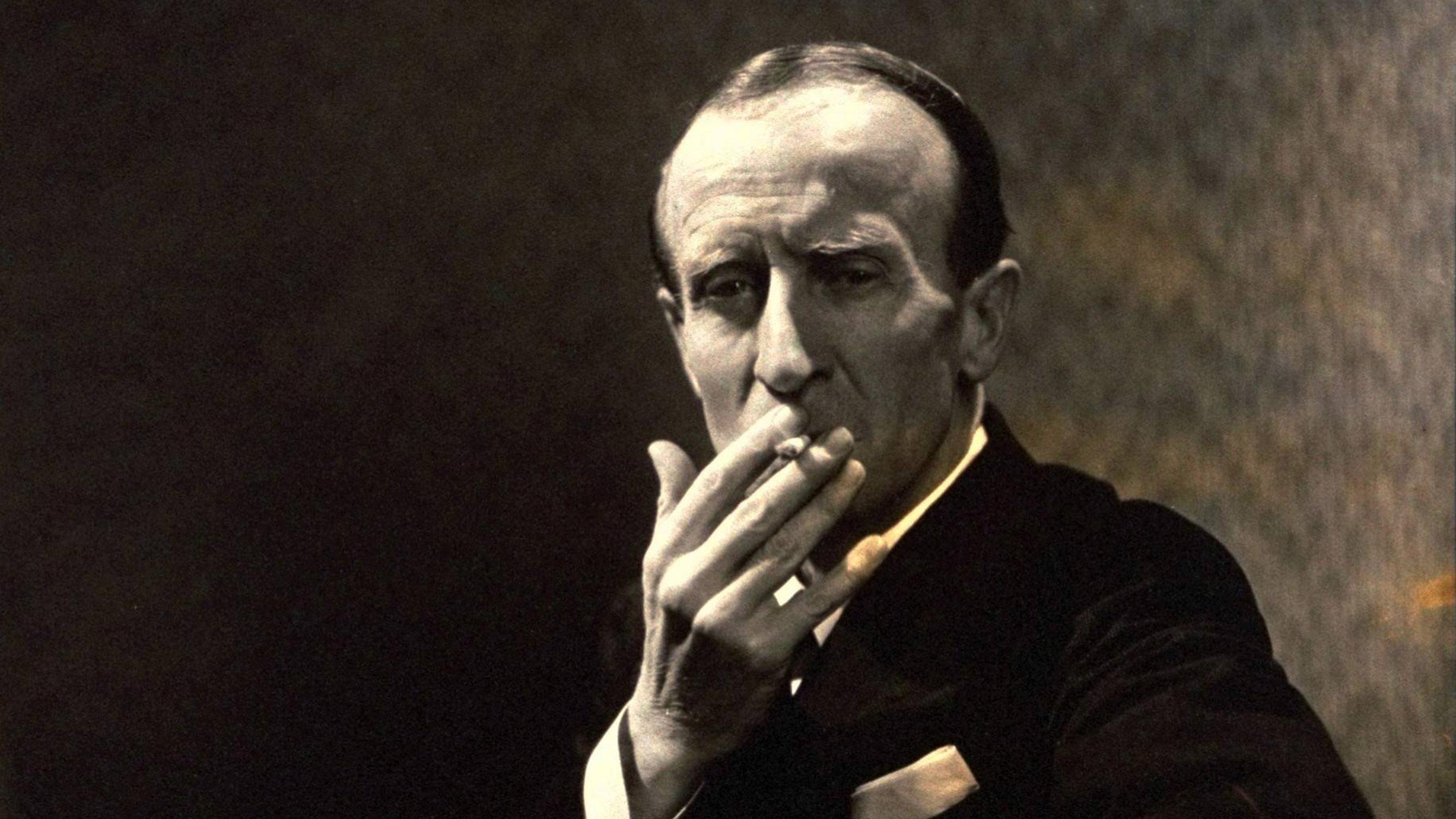

cover: portrait of Jacques Bergier

Jacques Bergier (1912 - 1978) - French journalist, writer and engineer, born into a Russian Jewish family - is best known for having written together with Louis Pauwels Morning of the Wizards: Introduction to Fantastic Realism (1960), a compendium halfway between a dystopian work of science fiction and an esoteric treatise capable of joining together, in a more or less coherent (and, above all, quite compelling) way borderline so distant from each other, such as alchemy, vanished civilizations, esoteric Nazism, magical socialism, the horror mythopoiesis of HP Lovecraft and Arthur Machen, the Hollow Earth and the theosophical theories of Madame Blavatsky.

The "way" that Bergier, "scientific popularizer, expert in fiction of the Imaginary," leftist "scientist who had made the Resistance and had been in the German concentration camps", proposed to follow was precisely that of the so-called "Fantastic Realism" (or "Magical"): a new method of investigation in which the most advanced scientific knowledge (including quantum physics) was destined to merge with ancient corporate sapiential, often of a secret and initiatory character (think of the alchemical, hermetic and theosophical strands), as well as with the studies fortiani on the paranormal and cosmic science fiction of the new century. From the point of view of Pauwels and Bergier, as Gianfranco de Turris writes,

"[...] there was no substantial difference between theories and hypotheses supported in scientific nonfiction and in imaginative stories: everything could be put on the same level... Moreover, more or less openly, they supported the thesis of a kind of "world conspiracy" which from time immemorial tried to prevent similar connections and therefore the discovery of new truths, to keep humanity at lower cognitive levels. "

This latter theme was dealt with above all by Bergier in his work The cursed books, where he came to postulate the existence of a sect of "Men in Black" as old as civilization itself, which for millennia has been used to hide, burn and remove from circulation certain texts considered particularly harmful due to the implications that they would be able to make arise in the minds of the most discerning readers. These enigmatic "Men in Black", that conceptually very little are detached from the famous ones Men in Black brought to the attention of the US public by ufologists as well as by Hollywood, they allegedly planned, among other things, the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, inspired the Holy Inquisition in its infamous "Witch hunt", persuaded heads of state to outlaw secret societies, issued censures, ordered the arrests of brilliant and innovative characters and finally formulated the so-called "initiatory secret", which if violated can even lead to immolation at the hands of the brothers and superiors.

“Our civilization, like every civilization, is a conspiracy. A myriad of tiny divinities […] divert our gaze from the fantastic face of reality. The conspiracy is used to prevent us from recognizing the existence of another world within what we inhabit, of another man within what we are. We should break the pact, become barbarians; and above all to be realistic: that is, to start from the principle that reality is unknown. By freely using the knowledge at our disposal, establishing unexpected relationships between the latter, accepting facts without old or new prejudices, […] we would see the fantastic emerge, together with reality. "

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

Even from these brief introductory notes alone, the reader can imagine how much our maddened by the recent literary vein of fantastic and science fiction fiction, which had taken the strings from the cosmic horror of the aforementioned Lovecraft and Machen to climb up to the sidereal depths of the stars. and infinite space. Passionate about the genre from an early age (he read Jules Verne and Louis Jacolliot at just three years old and later literally devoured the works of Philip K. Dick, Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Gustav Meyrink, Jorge Luis Borges), Bergier thus declared out of his teeth his literary intentions and the eclectic method of investigation in the introduction to the already mentioned Morning of the wizards:

«We think that in the very center of reality intelligence, even if it is hyperactivated, discovers the fantastic. A fantastic that does not invite escape, but a deeper adhesion. It is through a lack of imagination that writers and artists seek the fantastic out of reality, in the clouds. They only derive a by-product from it. The fantastic, like other precious materials, must be extracted from the bowels of the earth, from the real. And authentic fantasy is quite another thing than an escape towards the unreal. »

It is therefore not surprising to find an essay by Bergier in our hands, Praise of the Fantastic - in Italian edition thanks to the types de The Palindrome / The Three Deserted Seats, translated and edited by Andrea Scarabelli who also signs an extended commentary in the appendix - completely dedicated to the profiles of those he defined magical writers, creators of openings on "other" worlds, (im) possible universes different from ours and nevertheless coherent, parallel or alternative dimensions that open in the folds of the Real or under the veil of Maya, archaic hyper-technological pasts and dystopian futures that echo the Lovecraftian prophecy about the imminent coming of a "New Dark Age".

Already in Morning of the wizards, Bergier framed the various cultic and cultural currents ascribable to the sapiential strands of esotericism and occultism as residues of "a very ancient knowledge of a technical nature applied simultaneously to matter and spirit", To the point that abstract fantasies would not appear on the exhibits kept in museums, but"precise technical prescriptions, keys to open the powers contained in man and in things" [TO. Scarabelli, Jacques Bergier, or fantastic realism, p. 288]. Conversely, ours will also advance a "technological" definition of magic, "technical residue of more advanced civilizations than ours and today disappeared, whose phenomena are as incomprehensible to us as a transitor radio would be for primitives»[Ibid, p. 289].

In Admiration (this is the original title ofIn praise of the Fantastic), in addition to the already mentioned Lovecraft and Machen, Bergier's pen wants to bring to the knowledge of the reader other great epigones of the new wave of the Fantastic: Robert E. Howard and Abraham Merritt, Ivan Efremov and Stanislav Lem, JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis, John Campbell, John Buchan and, finally, Talbot Mundy. All these authors, although considered by the author as "rationalists", had the merit of having been able to transcend this rationalism, resulting, with their imaginal creations, "in metaphysics, religion, myth and even the sacred" [de Turris, p. 15]. Agreeing with Tolkien, Bergier upheld man's own prerogative, through fantastic literature, to create; in this, being recognized to the human race a possibility that he shares only with God [Ibid, p. 272].

« A magical writer is caught by a certain demon and ceases to be so for reasons no clearer than those of the psychology of genius or conversion. "[P. 29]

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

Bergier's innovative point of view, who went so far as to argue that «the only interest of science is that it provides science fiction ideas» [p. 267], among others attracted the applause of the science fiction historian Charles Moreau, who paid homage to him with the following words of admiration [cit. in Scarabelli, op. cit., p. 273]: "Bergier has formed a link between two worlds, amazed by the fantastic side and the evolution of technology", Giving them"noble characters, penetrating the paradoxes of science and the marvelous"And adding that, on the other hand,"science needs the wonderful to be reborn, like a phoenix».

With these premises, The morning of the wizards was a cause of confusion and controversy when it came out in France in 1960: in any case this does not affect the possibility of considering the working method of Bergier and his colleague Pauwels as a real revolution in progress, «a new synthesis between calculating reason and spiritual intuition that overwhelmed the principles of the nineteenth century», which ours was able to frame as "jailer and executioner of the fantastic»[Ibid, p. 274], and which Scarabelli paraphrases as "undertow of an Enlightenment that has eliminated any other tradition to propose itself as the only truth", In all respects similar to"a form of secularized monotheism».

In the "short century", in reverse, the fantastic forcefully re-enters the back door, through science itself (consider the Lovecraftian tale as a paradigmatic example FromBeyond, published in 1920) and as a consequence of the so-called "death of the realist novel", whose "killers" are to be recognized in the Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann and in Finnegans Wake by James Joyce.

In this regard, it was Borges who relegated Realism as a simple episode in the history of the art of words: great literature, at any time, was never realistic, anywhere and at any time in human history, having triumphed over the Imaginary, with the sole exception of the historical period between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. To this is added the arguments of the Romanian historian of religions Mircea Eliade, who expressed the opinion that fantastic literature cannot disappear, as "an extension of mythological creativity and dream experience" [Ibid, p. 278] - an idea that emerges in Myths, dreams and mysteries (1957) and, more recently, in the essays contained in Occultism, witchcraft and cultural fashions (1983)

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

We are now going to briefly outline the profiles of the "magic writers" presented to the French public by Bergier in this "In Praise of the Fantastic": profiles - as we shall see - heterogeneous, characterized by profound differences both in background cultural as well as personal worldview, and yet all heralds of "other" visions and creators of alternative imaginal universes.

The dystopian vision of John Buchan (1875 - 1940), the first author presented by Bergier, was based on human society and on the fragile relations of force and communication that determine its functioning on a global level. In his novels the conception ofexistence of an invisible power, wisely concealed behind the silhouettes of those who are commonly considered by the masses to be the truly powerful. Likewise, Buchan suggests that underneath the visible wars an invisible, “subtle” one is fought, like the one fought in ancient times by the Druids against the Christian colonizers. The real power, in any case, is that exercised on the minds of others: and only those who have a truly "centered" will can modify events at will (this is what is usually defined as "magic").

With his visions that we do not hesitate to define fanta-geopolitics, Buchan is today remembered as one of the most prophetic and "clairvoyant" novelists of the first postwar period. On the other hand, he knew what he was writing about, having also been a well-known and appreciated politician as well as a novelist: among other things, at the time of his death in 1940 he held the position of viceroy of Canada. Despite this, however - to use Bergier's words - Buchan was able to transcend "the narrow enclosure of the narrow materialism of respectable people and official culture", if only because he himself considered himself in possession of the so-called "Second view", a type of clairvoyance mentioned by peoples of Celtic culture, brought to the attention of academics, for the first time, by the essay of the Scottish Reverend Robert Kirk The Secret Commonwealth, written in 1692 and first published in 1815.

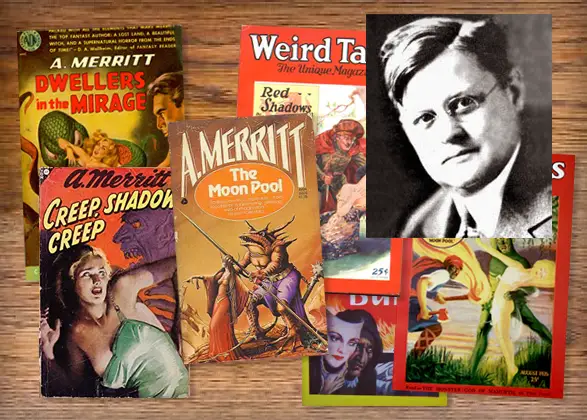

Completely different is the "vision" of Abraham Merritt (1884 - 1943), whose novel we have already reviewed on our pages Ishtar's ship, also recently published in Italian by Il Palindromo in the same series as this one Praise of the fantastic. Merritt's imagination takes its "the" from the theosophical doctrines concerning the existence of cyclically repeating eras according to cosmic evolutions, as recalled almost everywhere in traditional cultures (Hexiodean age, Yuga, "Suns", etc.), and of ancient pre-human bloodlines residing on islands or continents that later occulted or sank due to floods or other cataclysms.

These are the themes that underpin the narrative skeleton of some of Merritt's most significant novels, from The well of the moon a The face in the abyss, da The dwellers of the mirage a Strip, shadow!, which refers explicitly to the myth of Atlantis [p. 68]. Other works by him are instead focused on the theme of witchcraft: this is the case of the story The women of the forest and novels Seven Steps to Satan e Burn, witch, burn. With particular regard to the writings of this "witchcraft" vein, Bergier exposes to the reader his very personal hypothesis: the framing of Nazism, in all its "rites" (sacrifice them and not), as a "cursed religion", whose "blood offerings" would be addressed to "Other Deities" residing, in the same way as the immeasurable Lovecraftian deities, in the cosmic abysses [pg. 67].

Of the Welsh Arthur Machen (1863 - 1947) - which at the time was still incomprehensibly unknown in France despite the great success of the novel across the Channel The Great God Pan and above all from the story The angels of Mons - Bergier outlines his youth spent classifying occult books and taking an interest in alchemical texts, then underlines his adhesion, at the insistence of his friend AE Waite, to the famous Secret Association of the Golden Dawn: the Golden Dawn [p. 80-1]. But what is more important for the purposes of Bergierian "Fantastic Realism" is the close link, in the Machenian mythopoeia, which exists between the wonders of new science and its risks, which on the contrary are anything but newFar from adopting a disenchanted or moralistic view, Machen merely suggests to the reader the possibility that apparently harmless scientific operations are able to plunge experimenters into nightmare scenarios, not too dissimilar to those of the Sabbath and demonic possessions [p. 86]:

“The naive materialism of the XNUMXth century has declared bankruptcy. The terrible reality of the occult powers of matter was brought to light by Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Deep psychology and the horror of concentration camps have laid bare the dark forces that control the rational soul, without it realizing it. Machen's is an eternal vision, the symbols of which agree with the reality revealed by science. »

And again [p. 103]:

« [While] ignoring the genetic code, Machen sensed that life, three billion years old, conceals ancient powers whose manifestations can be terrible. »

A real scientist (specifically a geologist and palentologist) was the Soviet Ivan Efremov (1908 - 1972). Bergier places him in the ranks of "magical writers" for his absolutely uncommon ability to blend his academic knowledge and those belonging to the folklore of the Russian steppes (and beyond) with an enviable coherence: Meeting on Tuscarora, for example, is focused on the topos almost universal of the miraculous fountain and thewater which heals wounds and ensures eternal life; Olgoi-khorkhoi on the survival of a prehistoric monster in modern-day Mongolia [p. 106].

However, it was thanks to the enthusiasm caused by the first space explorations that Efremov's name spread beyond Soviet borders: The Andromeda Nebula, published in installments on “Techniques for youth” starting from 1957, it recorded great successes with audiences and critics, although at home there was someone not very accustomed to “Magic Realism” who considered the genius of the writer dangerous [p. 109]:

“The future of our author angered some Orthodox Communists. The "Corriere Economico" dedicated an article full of insults to the book. In that future, in fact, no one would have talked about Marx, Lenin and Stalin anymore, but the names of the Greek gods would return: Mars, Venus, Zeus ... »

The protagonist of another of his novels, The razor's edge, is used as an alter-ego to express his (uns) ticulating "vision", to be compared with the situation of intolerance in which he was increasingly in the presence of the Party: the character in which Efremov mirrored himself, "Opposed in the Stalin era - and even after -, he will abandon the USSR and found in India an alliance between the Marxist dialectic applied to science and Tantric magic" [pg. 113].

Perhaps it was also because of his "escape" from the present (and from "historical time" properly understood) that the novel was particularly successful among young people: chapters de The Andromeda Nebula [pg. 110]. Yuri Gagarin himself, the first man to orbit the planet Earth, confessed to Bergier that he had decided to undertake the process to become an astronaut after reading the aforementioned novel by Efremov [pg. 110].

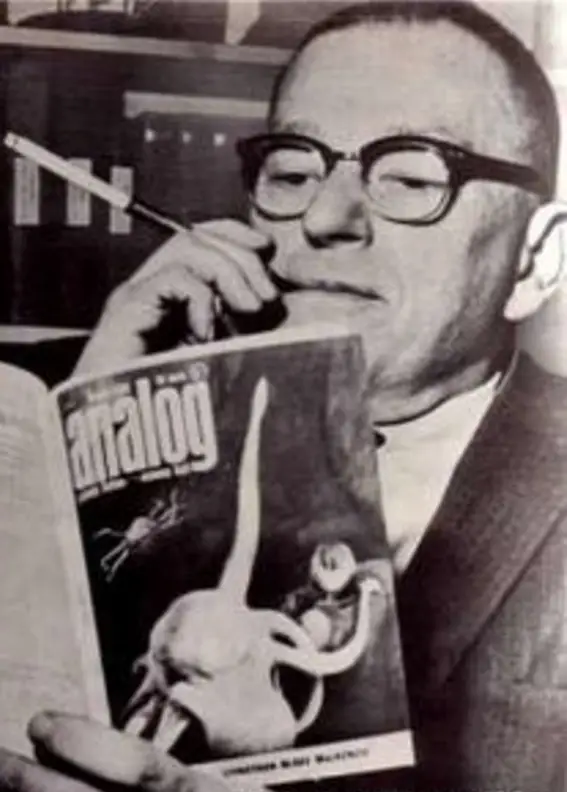

In the person of the American John Wood Campbell (1910 - 1971) Bergier recognizes the initiator of modern science fiction: his first short story The defeat of the atom, published in 1930, "contains at least one prophecy per line": it anticipates, among other things, the advent of great modern computers, «Total material energy, the annihilation of matter with an energy yield equal to one hundred percent». In the sequel, published a few months later, they peep out artificial intelligence and sentient automata [p. 128].

His "clairvoyant" genius, combined with a remarkable prolificacy, will lead him to be the first to investigate some of the most exciting themes deriving from the most modern scientific perspectives: quantum and nuclear physics, intergalactic travel, the symbiotic relationship between man and machine. The mantle of Aesir (1939) is inspired by the studies of the physicist PAM Dirac on the "positron" and on the so-called "anti-light" [p. 139]; The "Thing" from another world (1938) experienced successful cinematographic adaptations, the most successful of which is that of John Carpenter (The Thing, 1982), a real “cult film” of the genre.

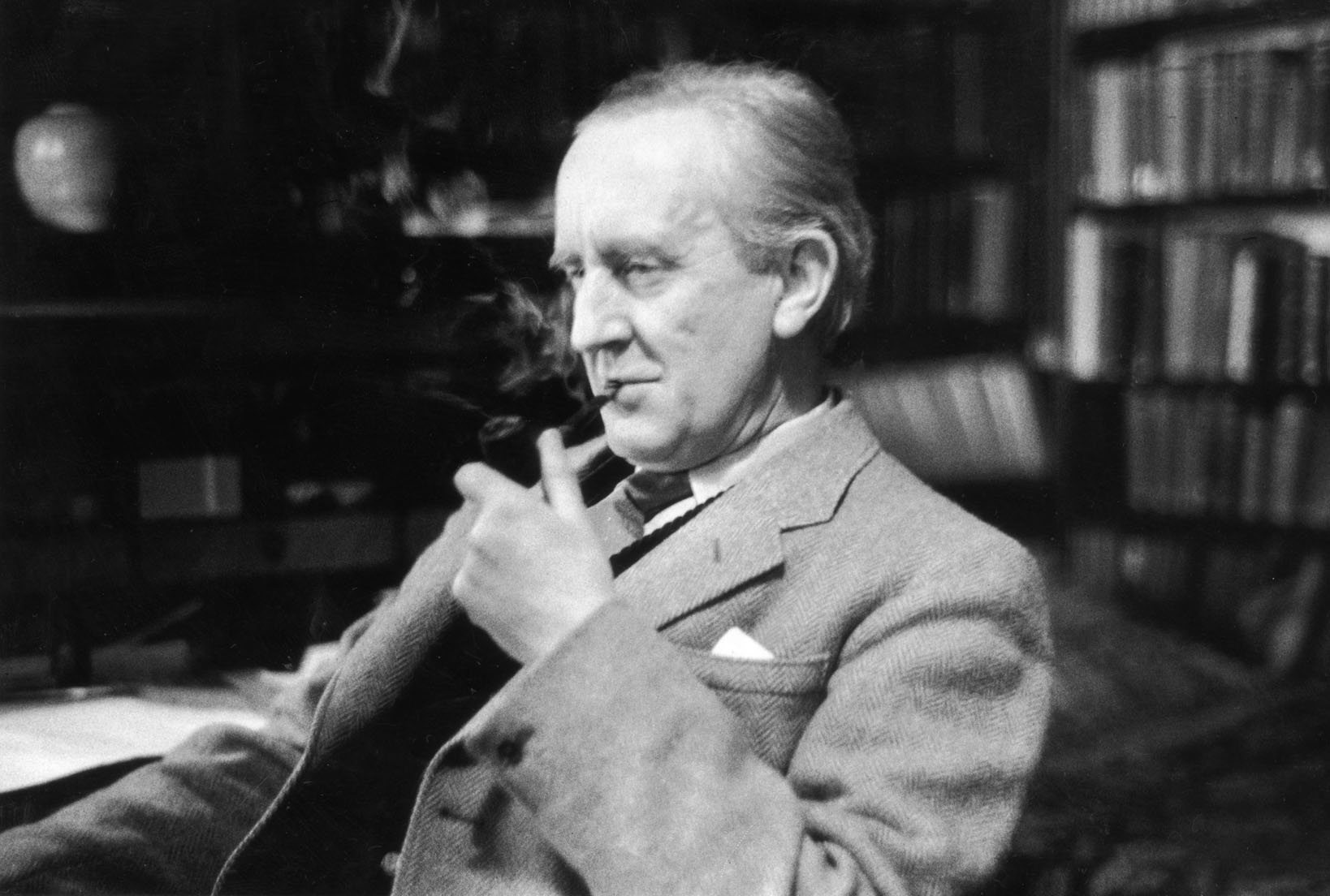

Decidedly opposite in its predominance of Myth over science is the mythopoeia of another of the most paradigmatic "magic writers" on Bergier's list: the British philologist and linguist John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892 - 1973). Real and true demiurge of the word (on the other hand, it was he himself who affirmed that «the authors of fairy tales are creators of universes"[P. 153]), Tolkien strikes Bergier first of all for the painstaking coherence and accuracy (think, for example, of the creation of real idioms) that permeate his entire work, as well as for his incredible collective archetypal power, mere psychology of the author [p. 148]:

« Never has an imaginary world been invented so multiple and provided with coherent internal laws, so pure, as well as uncontaminated by the author's psychology. Never has an imaginary world touched the authentic human condition without falling into allegories. "

The success of Tolkien's works was preceded and favored by the popularity of the American Robert E. Howard (1906 - 1936), committing suicide at the age of thirty, considered by Bergier a "genius from outside»Like Lovecraft [p. 218]. Similarly to Tolkien and even more to Merritt, Howard draws heavily, for the creation of his saga of Conan the Barbarian, from ancient traditions concerning the existence of supposed pre-human populations, antediluvian civilizations and frightening cataclysms that would have progressively dramatically changed the face of planet Earth. The explicit mention of Hyperborea, as well as the submerged continents of Lemuria and Atlantis suggests that Howard's greatest influence in this regard was The secret doctrine by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the "Bible" of Theosophy.

Even more noteworthy is a revelation Howard himself made to his colleague Clark Ashton Smith in a letter written in 1933: he he admitted that he had written Conan's adventures' in a state of semi-automaticism: Conan himself was next to him dictating the stories. He considered him a real character "[p. 225]. Here, however, meditate on the fact that other writers of the same generation as Howard (such as the Austrian Gustav Meyrink, the Irish WB Yeats and the Portuguese Fernando Pessoa. , all three fully attributable to the group of "magic writers" according to Bergier's criteria) experienced semi-automatic writing in a state of unconsciousness.

Similarly to many of the authors so far mentioned, too Talbot Mundy (1879 - 1940) believed that civilizations had arisen and waned several times, which is why he dedicated a cycle of five books (The Nine Strangers, Jimgrim, The Devil's Guard, There was a door, Black light) to survival in our age of secrets of ancient civilizations, which were in possession of more advanced technology than ours. Also deeply influenced by Blavatsky - but also by others who have written on the theme of the secret kingdom of Agharti / Shamballah (R. Guénon, F. Ossendowsky, Saint-Yves d'Alveydre) - Mundy puts the characters of his novels into situations adventurous and caledoscopic, nevertheless indulging in valuable reflections of an esoteric nature, halfway between Plato and EA Poe [p. 237]:

“Instead of aspiring to equal the wisdom of the gods, why not admit that our dreams bind us to the universe we came from - before falling into space-time - and to which we will return? Some dreams are memories of the wisdom acquired in the infinity before the birth of the world, and the wisest of the sages believe that earthly life is only a dream. »

Il mundus imaginalis of the Irish Clive Staples Lewis (1898 - 1973), while anticipating here and there some recent scientific discoveries or ideas (for example, as we will see shortly, the existence of "radiation belts" around the globe), was instead profoundly influenced by the Gnostic doctrines that they see the human being as imprisoned on this planet and subjected to the "subtle" dominion of the Eldila (plural of Eldil), immaterial beings that inhabit the space between one world and another, having traditional correspondences with the Archons and the Fallen Angels. The Eldil who commands the sublunar world has the characteristics of the Demiurge of the Gnostics [p. 174]:

« The Eldil that dominates the Earth is insane. He has abandoned the great brotherhood of the Eldila, no longer admits the authority of Maladil the Younger [the creator of the stars, ed] and exercises a ruthless tyranny on our planet. To prevent it from extending its dominion to other planets, the Earth is surrounded by a radiation belt. All this was written in 1938: in 1959, Van Allen and Vernoff discovered that our planet is indeed surrounded by a radiation belt. »

A deeply believer following a dramatic conversion ("an unconditional and terror-filled surrender" [p. 173]) which took place in 1929, Lewis framed the cosmic drama of humanity, so dear to the Gnostic currents of early Christianity, in an atmosphere eschatological (from "last times") that makes from frame to the three titles of his first work, the "fantasy trilogy" formed by Away from the silent planet, Talk about it e That awful force. In his very personal, half theological and half literary conception, the author considers science and science fiction ("especially that which incites man to abandon the planet" for the purpose of space exploration) as "instruments of the Eldil dark, lord of this world "[p. 175].

At the controls of this Princeps Huius Mundi the followers of theNational Institute of Coordinated Experiments, which in Bergier's opinion "singularly recalls some modern transnational organizations" in its desire to establish a sort of "dictatorship of a neo-Hitlerian rationalism" [p. 179]. In what the French writer defines "The most oppressive lines written in the twentieth century", Lewis paints our age with Lovecraftian tones [pp. 184-5]:

« The physical sciences, good and innocent in themselves, had already begun to be distorted and subtly maneuvered in a certain direction. The hope of reaching objective truths had faded in scientists; the result was indifference to this problem and the exclusive pursuit of pure and simple power. Chat about vital momentum and flirtations with panpsychism promised to restore the wizards' Anima Mundi. The dreams of a distant and future destiny of man unearthed from the low and restless tomb the old dream of the Man-God. [...]

Would there be incredible things, since they no longer believed in a rational universe? Would there be obscene things, since they held that all morality was a mere subjective by-product of the physical and economic situations of men? The times were ripe. According to the point of view accepted in Hell, the whole history of our Earth led to this moment. Now, finally, there was a real possibility that the Man cast out of Eden could shake off that limitation of powers that mercy had imposed on him as a protection against the extreme results of the fall. If this plan succeeded, Hell would eventually incarnate. »

We are faced here, as often happens when reading the creations of the "magic writers" of the Bergerian list, for example a radically and philosophically pessimistic position; the same that Bergier traces, while not ignoring the profound differences between the two authors, also in the work of the Pole Stanislaw Lemm (1921 - 2006), the second "pen" of the Eastern Bloc that ours brought to the attention of the French-speaking reader.

In Lem's novels, Bergier writes, "we collide with the incomprehensible ... the universe is too complicated for us to understand" [p. 190]. The universe the reader of Solaris, for example, is the spatial paradigm of the "Totally Other": the non-Euclidean architectures and geometries of Lovecraftian memory that arise from the ocean are completely beyond any human reasoning and usefulness, suggesting rather the Hindu conception of space-time manifestation as līlā, "game", "Distraction", "pastime", but also "mere appearance", "simulation" [p. 191]:

«The ocean not only has an" other "intelligence, but also possesses technical means superior to those we know. […] Parts of the ocean take on forms, generate architectures, according to laws that are impossible to explain. Is it art? Mathematics? Is it just a game? Or perhaps we are faced with a completely incomprehensible form of intellectual activity? Nobody knows, nor will they ever know. »

Clemont's pessimism is yes cosmic but, unlike Lewis's, it is completely devoid of the "sacral" dimension: Lem on the other hand, unlike Efremov, embodied for the Soviets the "model" scholar, atheist and firm in his rationalistic and materialistic beliefs , capable of eventually leading to post-spiritual currents such as the cosmist one, but never in “prophetic” and “apocalyptic” concepts like Lewis's, nor oriented according to a “mythical-traditional” perspective as happened for Tolkien, Machen, Merritt and Lovecraft.

The story is paradigmatic in this sense The truth, in which a team of scientists discovers with utmost desperation that real life develops amidst the high temperatures of the incandescent plasma: «the Sun and the stars are alive, but we are not!","We are irrelevant moribund matter» [p. 195]. "Materialistic science has reached its limit, and for Lem there is nothing beyond materialism," Bergier says laconically. "The work thus closes in the name of rationalist despair" [p. 194]. Another tale from Clemont, From the memories of Ijon Tichy, advances the hypothesis that we human beings "are only recordings on magnetic tapes that delude themselves into living"! Bergier glimpses an attitude in the Soviet writer here that he does not hesitate to define diabolic [p. 196]:

"Clemont uses the evidence of the existence of the soul or mind (telepathy, clairvoyance and premonition) in the opposite sense, showing that we are not even the automatic machines imagined by behavioral psychology, but recordings devoid of material reality »

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

In conclusion, what view can be opposed to the "narrow materialism" that emerges from Lem's Soviet science fiction? There foundation stone of the new paradigm - that, in fact, of "Magic Realism" - is according to Bergier to be traced in the correspondence between man and universe (microcosm and macrocosm), a very ancient assumption well known to magicians, alchemists and kabbalists that the French writer updates to 1969 [p. 198]:

« the brain is like a computer that can build a model of the cosmos in its own circuits. »

It's still, in a Baudelairean way [p. 199]:

«The whole cosmos is an enormous encrypted message, open to man. "

18 comments on “Jacques Bergier and "Magic Realism": a new paradigm for the atomic age"