Although they lived one century after the other, in the biographies of Blake and Yeats it is possible to glimpse two parallel lives, based on some specular guiding ideas that guided their artistic and literary activity: the ideal of " religion of art ”, the saving mission of the artist, the emphasis placed on the imaginative faculty for the purposes of the process of self-realization and the announcement of the advent of a new era to come.

di Marco Maculotti

He is one of those great artists of God who proclaimed mysterious truths to small covenants. While the others had talked to theologians and magicians, he talked to poets and artists. The others took their symbols from theology and alchemy, he from spring flowers and summer leaves; but the message is the same, and the truth proclaimed is that which God announced to the red clay at the beginning of time.

- WB Yeats, "William Blake: A Biography"

On the one hand William Blake, perhaps the greatest artist that England has ever produced; on the other William Butler Yeats, probably the finest Irish man of letters in history. Who better than the two of them could speak of the "magical" power of the imagination and of the astral escapes into the imaginal world to bring back, on the bare earth, some spark of eternal Truth? This is why this is to be greeted with enthusiasm recently published Mimesis (Milan 2015) William Blake and the imagination, edited by Luca Gallesi which contains two writings by William Butler Yeats on Blake's sacred rather than artistic vision: "William Blake and the Imagination" (1897) and "A Biography" (1905).

PARALLEL SCREW

Already to Yeats the golden thread that bound him to Blake must have been clear, despite having lived a century before him: in the essay "William Blake: a biography" he does not fail to list a series of episodes common to his biography as to that of Blake (as well as, we add, to that of other great modern writers, such as Lovecraft), as if to define a common substratum: the presence of voices in childhood, feeling alienated and derided by peers in adolescence, the refusal of school education and the use during the mature age of automatic writing (particularly famous, in this regard, for Yeats is the work The Vision).

Nonetheless, behind the purely biographical curiosities of the two, Yeats would like to highlight some guiding ideas that have shaped both Blake's work and his own: the "religion of art", the saving mission of the artist, the emphasis placed on the imaginative faculty for the purposes of the self-realization process, the announcement of the advent of a new era to come. In the integral vision of the world of the two - underlines Gallesi - "there is no space for the fracture between the artistic dimension, the spiritual sphere and everyday life", then citing an illuminating aphorism by Ungaretti referring to Blake (but which could very well also concern Yeats) which reads [p. 8]:

The true poet yearns for clarity: he is eager to reveal every secret: his own, the secret of his earthly presence, trying to know the secret of the progress of history and the reasons that govern the universe, trying to take possession of the secret of secrets.

As Gallesi points out [p. 69], «Blake's grandiose symbolic apparatus served Yeats as a powerful and concrete mythological school; in Blake Yeats he had found a poetic corpus that was linked to all his philosophical, aesthetic, artistic and above all spiritual interests through what seemed to be the announcement of a new universal religion', Also adding a note from 1892 by the Irish poet according to which' if he had not [and] made magic the constant object of [his] study [he would not have] been able to write a single line of [his] Blake '. It is certainly no coincidence that, after studying Blake's work, Yeats's interest in occultism became more and more preponderant, approaching the theosophical circles before and at Golden Dawn after.

Both Yeats and Blake "heralded a New Era that would overturn the values of theirs. Blake announced the overthrow of materialism represented for him by Bacon, Newton and Locke while Yeats reacted against the myth of progress which in his eyes was a huge lie"[P. 70]. Somehow Yeats renewed Blake's idea that art corresponds to the tree of life and science to that of death (or knowledge), the two legendary trees present in Eden. The intellectual, philosophical and spiritual horizons of the two were also very similar: "Plotinus, Böhme, Swedenborg, the Holy Scriptures, Milton and Blake's favorite medieval mystics are reflected in Celtic mythology, in Nietzsche and in the occultism loved and studied by Yeats" . Mostly in Nietzsche Yeats had found a thought that "flowed violently in the same bed where Blake's had passed".

Among Blake's great inspirers, the most influential were swedenborg, Jacob Bohme and other mystics and alchemists who spoke ofimagination like of the "Body of God", of the "divine limbs": from this intuition he drew as a corollary what not even his "masters" had understood, namely that "The communion of all living creatures, both righteous and sinful, aroused by the imaginative arts, is the forgiveness of sins preached by Christ" [p. 14]. He understood these Truths in his lifetime through a series of mystical visions: in one of the last years he confirmed that he wrote under the order of the spirits and revealed [p. 45]:

As soon as I stop writing I see the words flying around the room in all directions. Then the book is published and the spirits can read it.

The feeling of having been chosen from the moment of birth by divine intelligences for a spiritual mission which would have benefited the whole of humanity - or, at least, anyone who could have understood his revelations without being blinded by their dazzling light - accompanied him from his youth. A Swedenborg's prophecy in particular, she seemed to convince him once and for all of this, to the point of remaining etched in his mind throughout his life, as Yeats recounts [p. 22]:

Swedenborg had claimed that the old world would end and a new world would begin in the year 1757. From then on, the old theologies would be rolled up like a parchment and the new Jerusalem would come down to earth. We do not know how often this prophecy concerning the year of his birth rang in William Blake's ear, but it certainly could only have come back to him as his strange faculties began to manifest themselves filling the darkness with faces. indistinct and green meadows with ghost footprints.

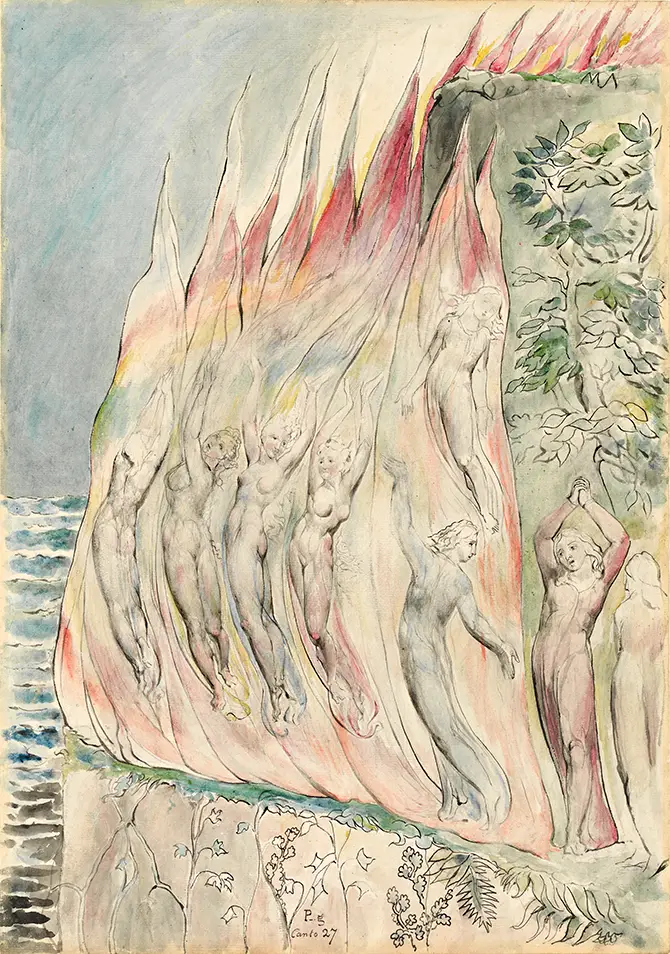

RETURN TO EDEN

Feeling also for this reason burdened by the chrism of the prophet, to whom Fate would have reserved a real saving mission in an England that in a few decades would have been upset by the advent and reforms of Cromwell, Blake defined his visionary ability as a "return to the Edenic state": in his thought Eden (or the New Jerusalem, or the Rediscovered Paradise) would reappear with the disappearance of the old theologies, thus leading humanity to a real union with the divine in the splendor of the light so long denied. In its eschatological vision, as deduced from The Argument e The Marriage of Heaven and Hell [p. 34]:

[...] "the right man", that is the imaginative man, walked in the valley of mortal life among roses and springs of water of life until the "villain", that is the man without imagination, arrived among the roses and springs and then the "right man" went angrily into the forest among the "lions" of bitter protest.

For Yeats as for Blake, to access the ultimate dimension (and at the same time primal) of reality, the old forms and structures must be demolished, thus forcing our ordinary senses and destroying the dense network of false deductions created by reason, which in Blak's eschatology is attributed a mirror function to veil of Māyā of oriental philosophies. The overcoming of the world of the senses thus becomes for Blake synonymous with return to the edenic state or, to put it with Mircea eliade, a real "level exit" experience e access to "sacred time". In the afterword in the appendix to the libretto, Gallesi rightly points out that, for Blake [p. 60]:

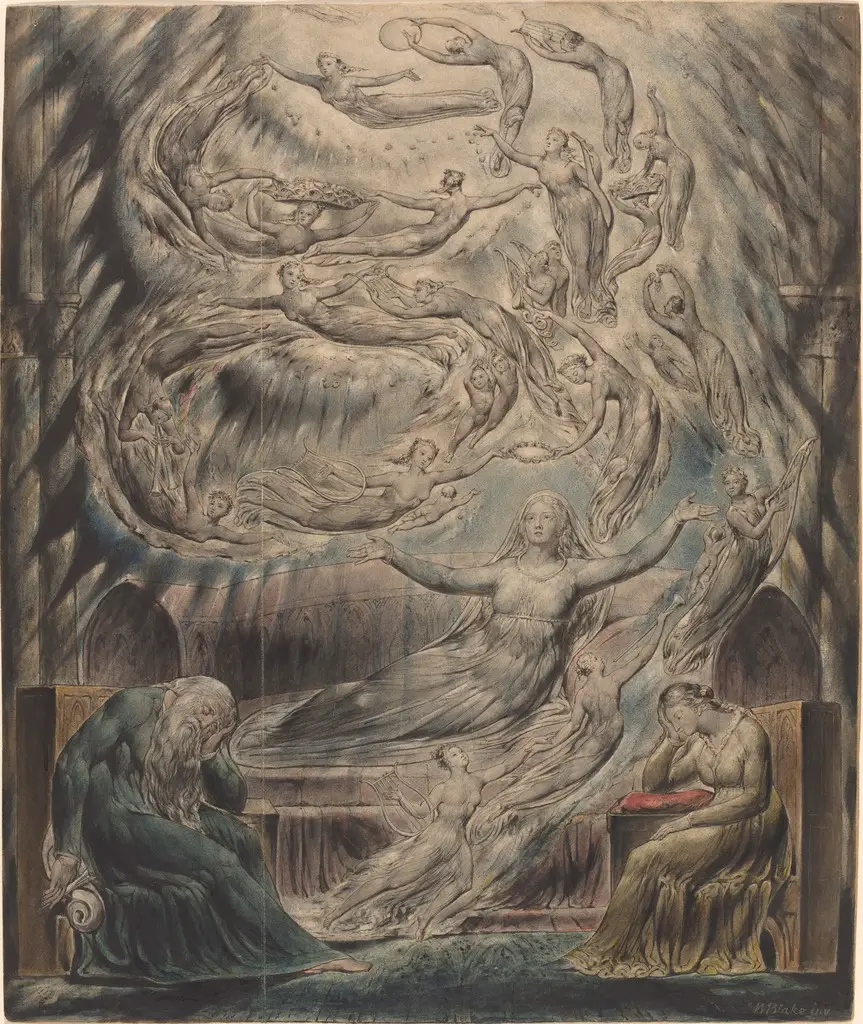

The visionary knows instinctively that originally God and man were one, and it is the task of art to show this truth to everyone; in this sense we can speak of prophetic art, not as a prediction but as a revelation, since the fall of man does not happen in a chronological but ontological dimension; the god-man fracture can be healed at any moment, if man is willing "to let himself be carried to heaven by the wings of the imagination and to open the doors of perception".

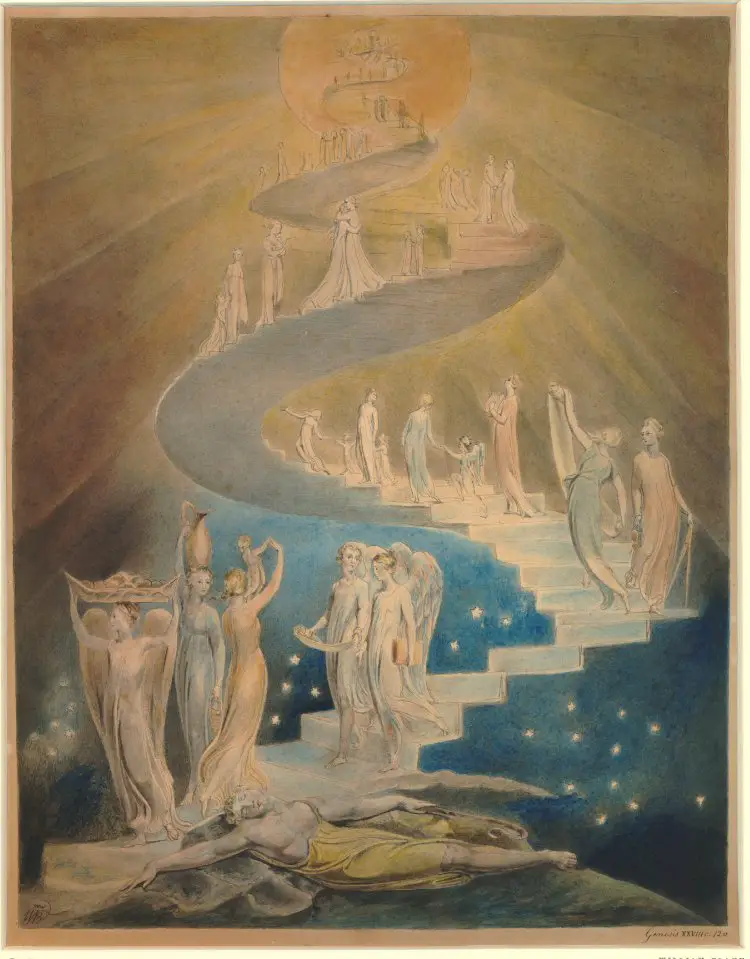

In Blake's eyes, the renewed encounter with God would be akin to a kind of reunion with our divine Self: one of the images most often used to symbolically describe the imaginative and visionary process is that of a lark which ascends to the sky and encounters another lark that descends halfway, and in which it reflects itself. In this sense that of the artist with the eternal Truth lying behind the veil of the senses is comparable to one ieros gamos between heaven and earth that is eternally renewed. An idea that certainly met with the acclaim of Yeats, according to which [p. 60]:

The poet must continue to perfect the forces and the earthly perception to sublimate them so that the strength and divine perfection come down to meet them, and the song of the earth and the song of the sky unite.

THE POWER OF VISION

Central to the maturation of these ideas was the observation of nature during his long London walks south in Surrey and north near Wellings' Farm, as well as the study of religious art among the vaulted ceilings of the Abbey and the graves of the neighboring cemetery: it was then that, Baudelairian, "the towers and spiers became hieroglyphs for the poetic imagination", to the point that he went so far as to write and repeat on several occasions that "the Gothic model is a living model" and to compare the great Gothic churches to the tomb of Christ [pp. 27-8]. From this point of view, explains Yeats [p. 28]:

Christ was the symbolic name given by Blake to the imagination, and the tomb of Christ could be nothing more than a refuge, where the imagination could sleep in peace until the moment when God would awaken it. What more beautiful refuge than this ancient Abbey could he have found? Outside the "indefinite" mass cackled and crowded while inside the "defined" forms of art and vision gathered and were at peace.

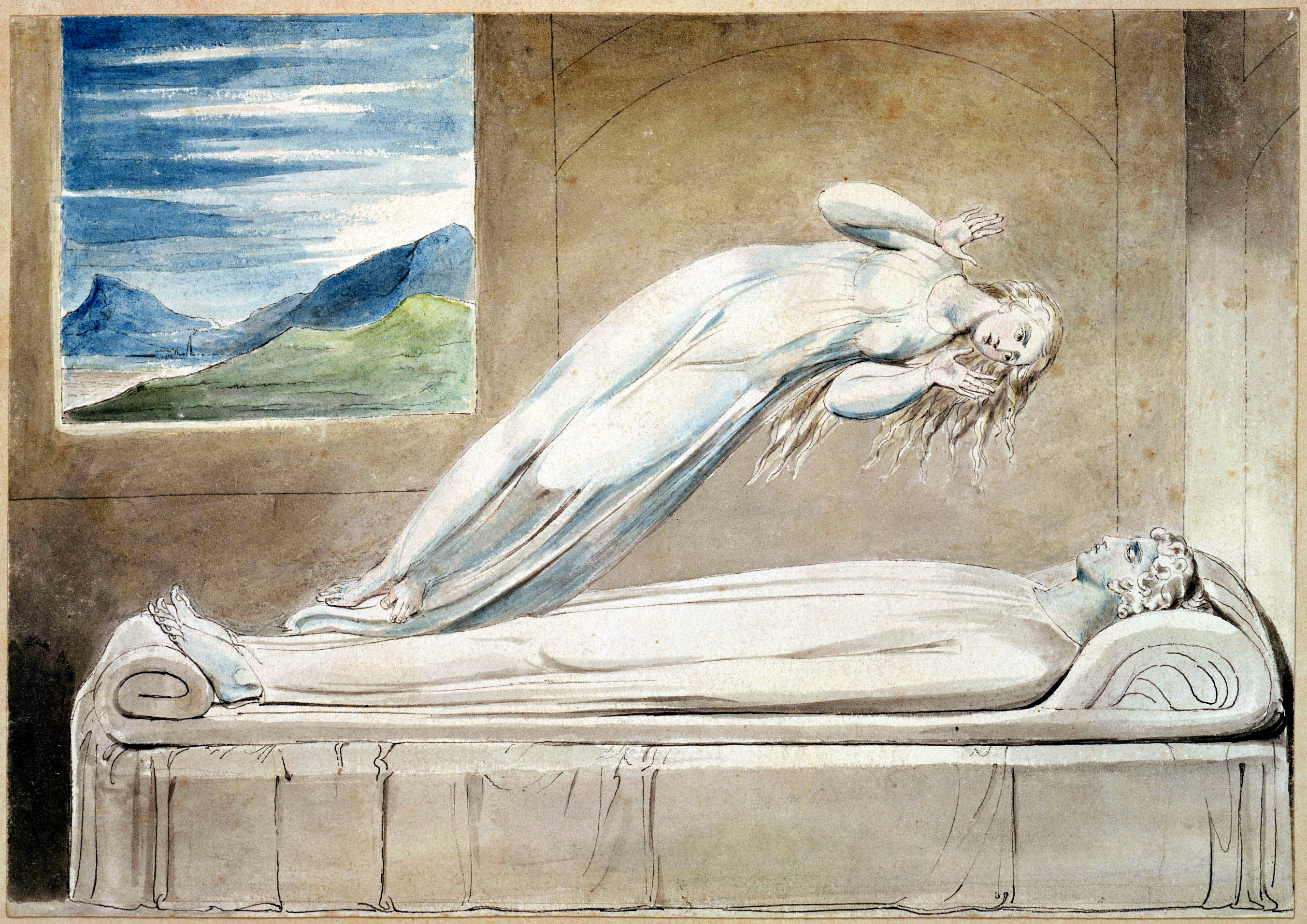

Among the visions he had one cannot fail to mention the moment in which, inside the Abbey where he carried out his apprenticeship, the 12 apostles appeared to him in spirit. But perhaps even more important to the artist's education were the dream visits Blake received from a shadow that resembled his brother Robert, who died prematurely (Blake also claimed to have seen his spirit ascend to heaven applauding with joy), who taught him to engrave the poems on copper and to print the illustrations and decorations in the margins of the poems.

Reconnecting perhaps unwittingly to the British tradition of the fairies as spirits of the deceased who accompany us while dwelling in an invisible dimension, Blake expressed the belief, in a letter sent to a friend, that "our deceased friends are really with us more than they appear to our mortal side", concluding that [p. 35]:

[…] Every earthly loss is an immortal gain. The ruins of time build abodes in eternity.

On the other hand, among the various apparitions in which Blake had the opportunity to come across over the years, there were also ghosts and feral entities (it seems that Böhme also experienced the same type of visions): Blake described fairies as "the rulers of the plant world" and for him the term "plant" meant "bodily" and "sensual". Blake experienced these visions when she left London in 1800 and settled in the village of Felpham, whose places greatly impressed his imagination: "Blake met kings, prophets and poets of all kinds, walking in ghostly processions on the edge of the sea, "Majestic shadows, gray but bright and taller than human"". She told a lady who lived nearby that she had witnessed the funeral of a fairy [p. 43]:

[…] I noticed that the large leaf of a flower was moving and below I saw a procession of creatures of the same size and color as the green and gray grasshoppers. They carried a body lying on a rose leaf which they buried singing and then disappeared.

THE ETERNAL CLASH BETWEEN LOS AND URIZEN

It is important to point out the ambiguity of the plant kingdom in Blak's eschatology: if on the one hand he believed that all "natural events" were symbolic messages from mysterious powers, on the other he saw it as the «kingdom of Satan», Connected precisely to the" body "and" sensorial "part of the human being, and therefore to the" lower "part of the imagination. Perhaps to define his dual vision of Nature, Blake teased during his stay in Felpham, in the form of an absurd parable, the story of the legendary Hayley, of whom it was said that he had two wives and that he kept one in a wood chained to the trunk of a tree [p. 45]. In his eyes, the Last Judgment «will not be the process managed by a personified legislator, but the liberation from 'nature' and 'bodily understanding'».

in Prophetic Books he exposes the reader to the belief that "God is found in the smallest effects as well as in the greatest causes"; since creation is God's "descent" due to man's weakness, everything on earth is visible as the word of God and as God in his essence. However, "that part of creation that we can touch and see only with the bodily senses is" infected "due to the power of Satan, which among other names also has that of" Opacity ": therefore, the other part that we can touch and see only with our spiritual senses and we call "imagination" is really "the body of God and the only reality" [p. 39]. Yeats writes in "William Blake: a biography" [p. 48]:

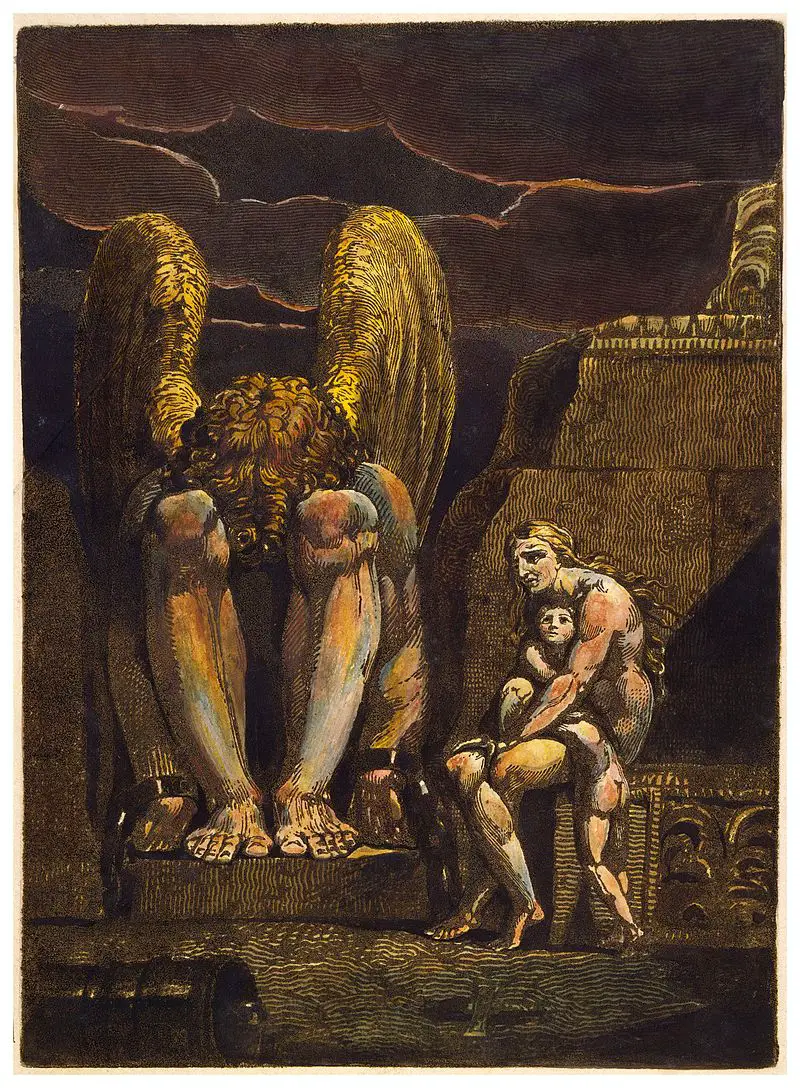

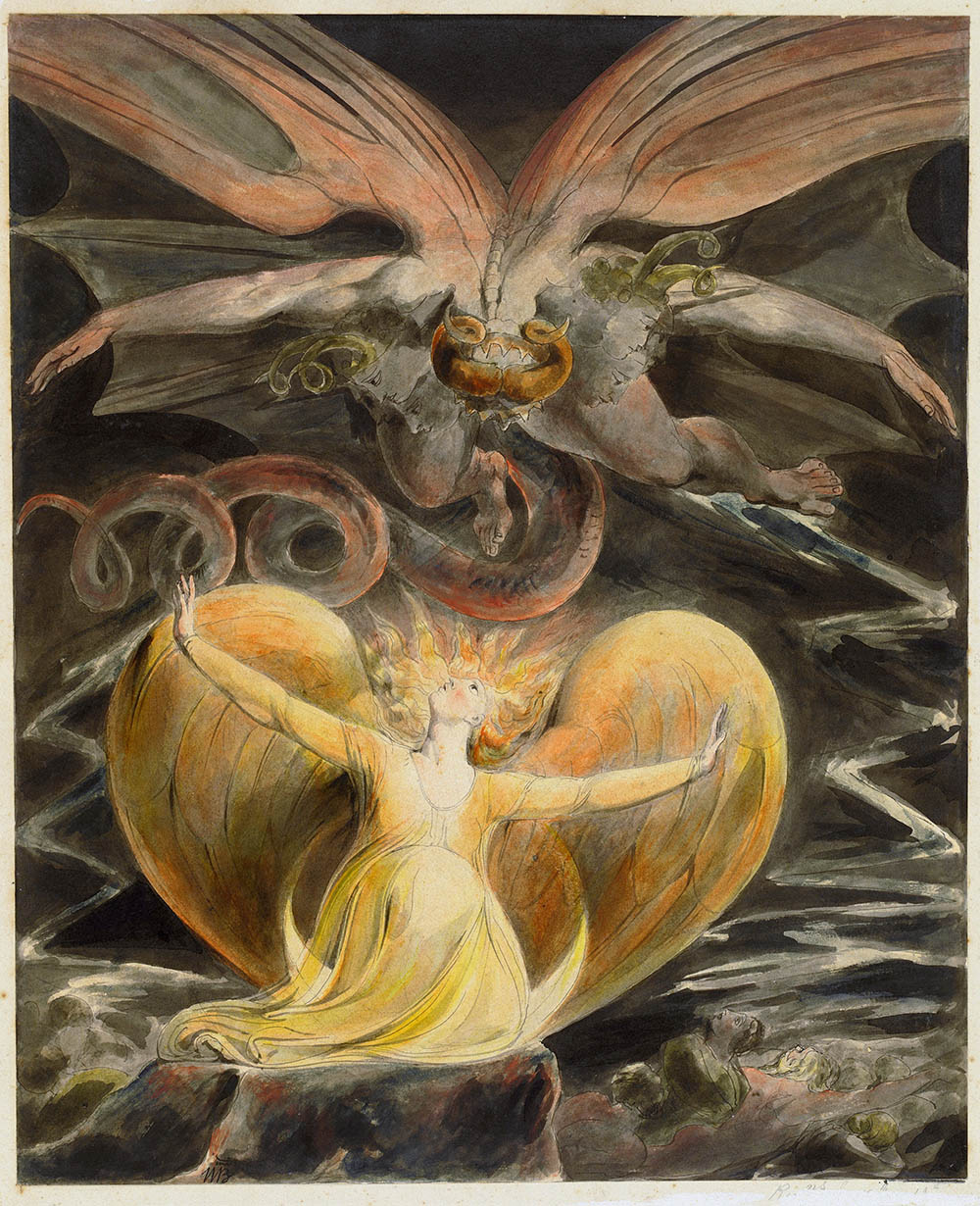

Blake saw […] everywhere the universal contrast between light and dark and was never peaceful. For him the universe appeared filled with an intense energy that was both infinitesimal and infinite, as in every blade of grass and in every speck of dust, Los, "the eternal mind", fought against the dragon Urizen, "The God of this world".

This Manichaean vision, which also has significant points of contact with the Iranian Mazdeism (In The Vision Yeats recalls how "without ever reading Hegel saw the world as conflict, since his mind had been full of Blake from childhood on"), is represented by Blake above all by the symbolic conflict of Los, the divine formative principle that is halfway between absolute existence and corporeal life (comparable to the Logos of the Neoplatonists), against Urizen, the satanic "god of this world" and "creator of dead laws and herald of blind denial" [p. 41]. To free himself from the grip of Urizen, man has only one way to go: embellish and enliven his existence with art and imagination, training his spiritual senses. ("Dilated" with respect to the ordinary "opaque" senses, subjected to the yoke of Urizen).

Opposing it in a dichotomy with reason, by which Blake meant the deductions related to the observations of the senses ("He firmly believed that cold and logical analytic reason was the most murderous of all faculties" [p. 27]), he placed the imagination as the only true pivot through which to free us from the mortality and precariousness of an existence otherwise devoid of a true superior foothold.

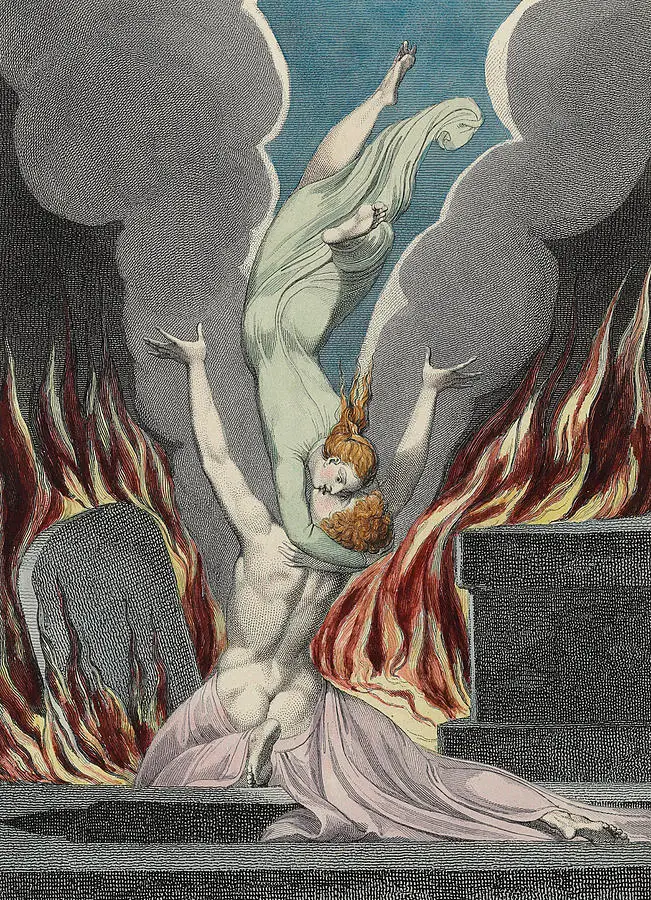

In his vision, "The sensations of this" stupid body ", this" shadow of earth and water "were nothing but semi-living things," vegetative "things, but the passion, that" eternal glory ", had made them become a part of the body of God ": this being what happens to the artist when, putting himself at the service of Art understood in its highest sense, he becomes in some way a Priest of the Imaginal, a real one pontifex for those who are able to fully enjoy his works.

THE BLESSED DEATH

This is also why Blake welcomed the passing, which took place at the age of 70, with open arms. In 1827 he was struck by a strange disease and was prey to chills and constant fainting. In the last months of his life he wrote to a friend [p. 50]:

I have come very close to the gates of death and have returned very weak, an old weak and shaky in body, but not in soul or spirit, not in my essence as a man which is the imagination that will live forever. Here I get stronger and stronger as this stupid body becomes corrupted. […] Raxman is gone, and we will soon have to follow him to our eternal home, leaving the delusions of Goddess Nature and his laws to free ourselves from the laws of numbers, in the spirit where everyone is king and priest in his own home. Such is the will of God both in heaven and on earth.

Shortly before his expiration he assumed a blissful expression and with a radiant look he began to sing all the things he saw in heaven. "He shook the ceiling," said one of those present; and a boarder of the same house, present at the moment of her death, said [p. 51]:

I did not witness the death of a man, but that of an angel blessed by the Lord.

11 comments on “WB Yeats, William Blake and the sacred power of the imagination"