The ancient traditions of Central and South America held that the Sun, as well as water, earth and the gods themselves, in order to prosper and guarantee the continuation of the world, had to be regularly fed with human blood, a concept that precisely among the Aztecs became of absolute, if not strictly obsessive, importance; nevertheless, the same conception was also found among the Maya, the Toltecs, the Olmecs and the Incas, as evidenced by the historical sources that have come down to us.

di Jari Padoan

originally published on CentroStudiLaRuna

According to an evident analogical concept, widespread and recurrent in the most disparate traditions, the flesh and blood of animals and / or human beings immolated in sacrifice and possibly consumed, represent an evident form of communion with the divinity (as already claimed in the XNUMXth century pioneers of anthropology such as EB Tylor and William Robertson Smith).

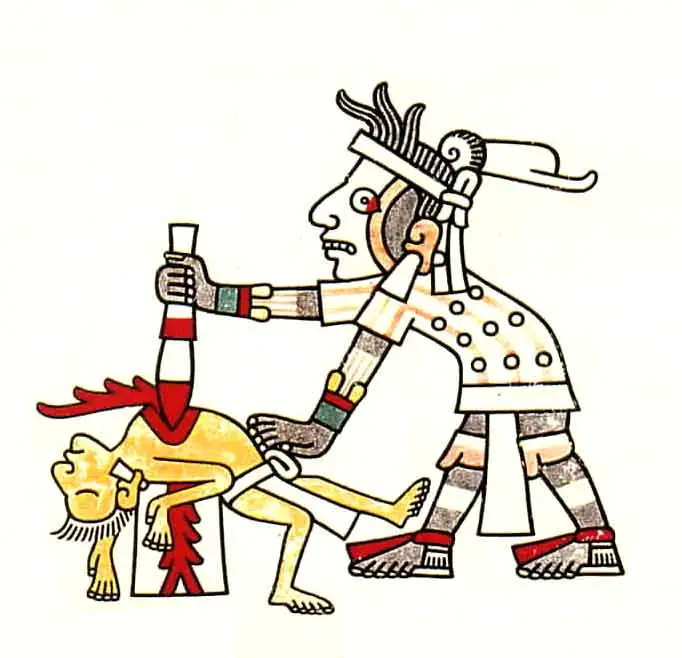

The most widespread sacrificial practice in the history of Mayan civilization seems to have been that ofexcision of the heart; an evident site of sacrifices of this type is the great avenue of the so-called Temple of the Warriors a Chichen Itza. Here we find a monumental and famous example of the type of "altar" with a sacrificial function called chacmool, considered another product of the Toltec cultural heritage: Chichèn Itza would in fact mean "well of the Itza", the name of a Toltec people or a Maya people in any case deeply influenced by Mexican culture.

Il chacmool it looks like a stone sculpture in the form of a human being lying in a particular position, with the head facing west. At the point of the immolation through the cutting of the breast and the extraction of the heart a small container was placed, which once filled with the blood of the sacrifice was placed in the temple. Widespread especially in the post-classical era, chacmools characterize areas, as mentioned, strongly influenced by toltec culture.

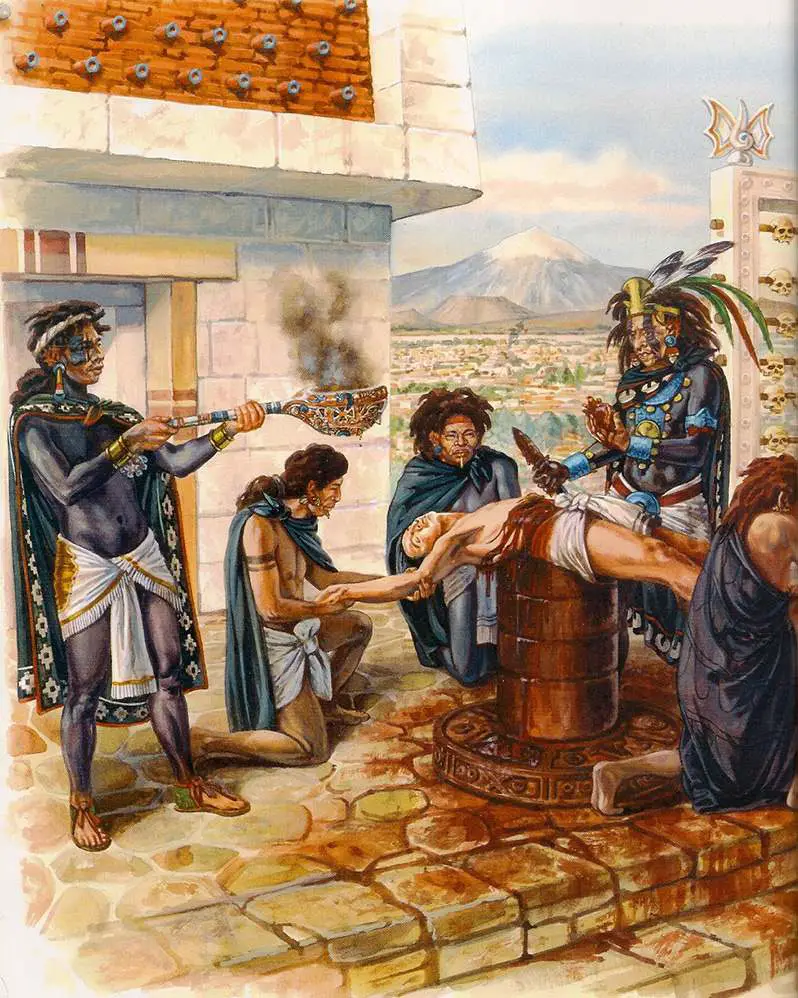

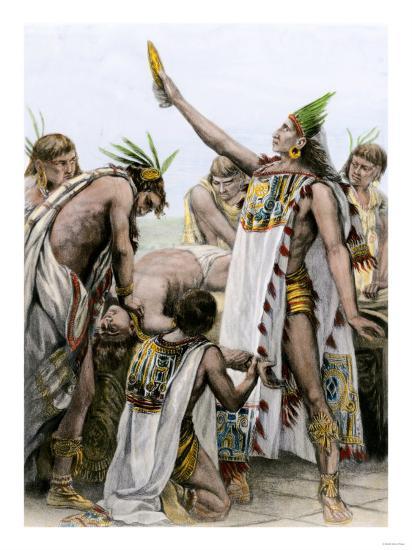

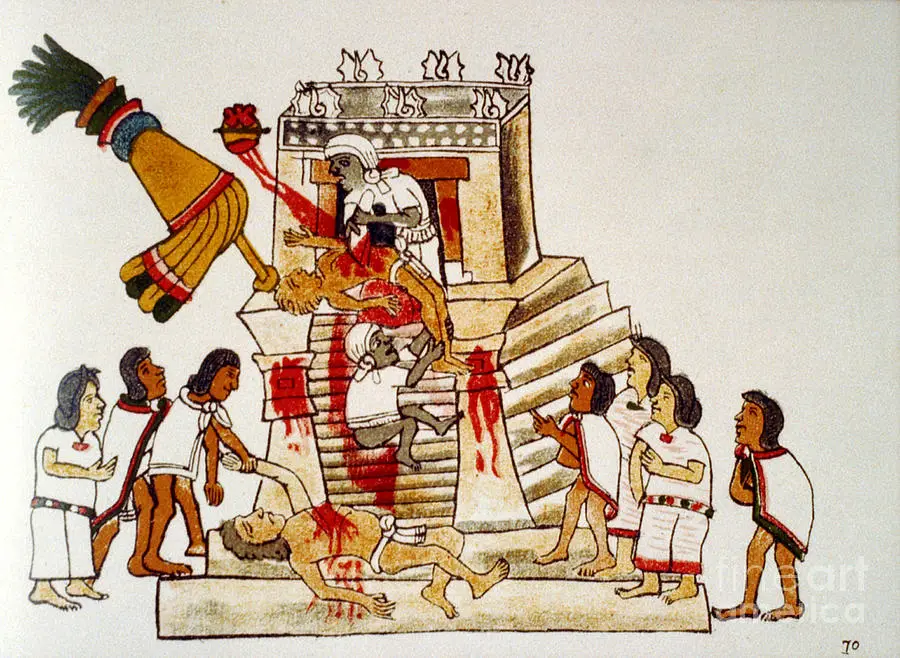

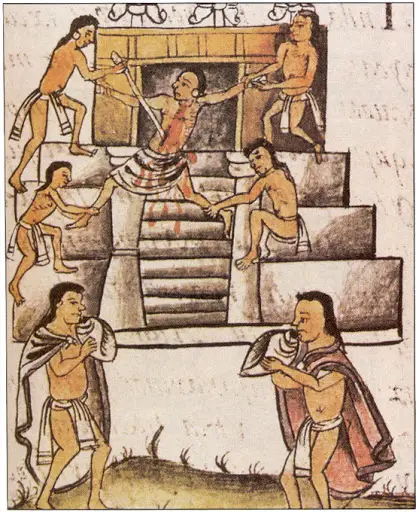

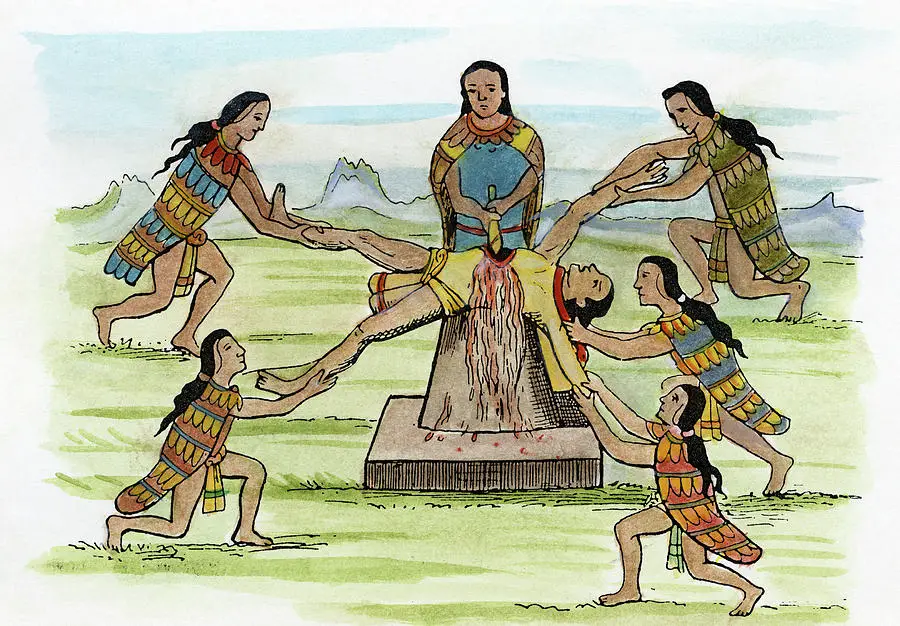

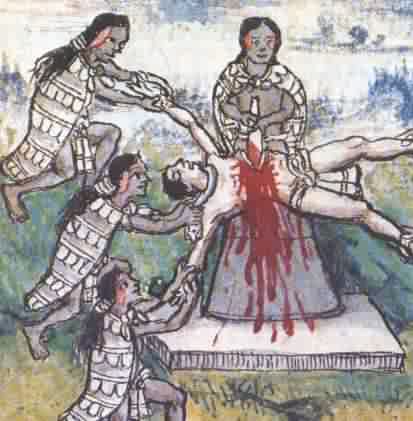

Among the Maya there were different types and degrees of officiants of the solar cult: the priest said ahkin or ah Kin (literally "that of the Sun") was the most important and above all assumed the function of prophet inspired by the divinity, connoisseur of writing and guardian of initiatory wisdom (which was taught to ahkin in special schools or circles called calmecac, an institution that will keep the same function and the same name among the Aztecs). THE four chac (the homonymy with the traditional god of rain is not accidental, as the officiants impersonated the aforementioned) arranged and immobilized the victim on the sacrificial altar, while the priest called nacom had the function of slashing the chest with a knife flint and extract the heart, to turn it in the direction of the Sun; the chacmool thus collected the gushing blood.

It is remarkable how the people involved in the sacrificial operation were divided and organized in a precise hierarchical structure, according to which each type of officiant was concerned with a single and delineated function; and this is a characteristic that is also found in the cultic sphere of some peoples of the Indo-European tradition. Just think of the Vedic sacrifice of Agni-şţoma, the "Praise of Fire", mentioned in the Chāndogya Upanişad and presided over by four priests (the brahman, the hotar, the adhvaryu, the udgātar) who performed different and interconnected functions.

Among the main deities of the Mayan tradition was the figure of Itzamna, founder of study and writing, father of the Sun and associated with the cult of fire, who in the myth also assumes the traits of a civilizing hero with sacral characteristics. The Itzamna cult would also gradually supplant the more mysterious figure of hunab ku, a creator god with much more absolutistic and above all elusive traits (although according to the Popul Vuh, among the most important primitive gods there were the two couples Tzacol and Bitol and Alom and Qaholom, in addition to the serpent-like creator deity Gucumatz / Kukulcan). This indecipherability of Hunab Ku, of which not even representations have been received, was explained by advancing the hypothesis of a particular antiquity or, on the contrary, of being a syncretistic figure dating back to the European colonial period, given certain characteristics that are decidedly similar to those of the God of Judeo-Christian tradition: the role of creator of the universe, the definition of "Father", unknowability of its true essence.

The cult of Yum Caax, or Yam Caax, god of corn and vegetation. The cultivation of corn, together with that of the bean (tzizé) was practiced in the Mesoamerican area at least from the fourth millennium BC, coinciding with the first urban settlements and the first products of pottery. We therefore understand the importance of the cult of Yum Caax, represented as a figure with a perennially youthful appearance, to whom, it is believed, boys were sacrificed in order to favor and give new vigor to the more fortunate peers.

In the post-classical period, probably due to the influences of Toltec assimilation, it assumes great importance, especially in a center like Chichèn Itza, the famous cult of the feathered serpent Kukulcan (which, as mentioned, takes the name of Gucumatz among the Quiché Maya), the same one that will come revered as Quetzalcoatl by the Aztecs. The festival of Kukulcan fell in the month of Xul, corresponding to the middle of autumn. It was in the ceremonies perpetrated on similar occasions, the tradition sanctioned the practice of the sacrifices requested by the gods. As it will happen for the Aztecs later, the Maya exploited prisoners of war in a double way: those considered the most valiant were destined for sacrifice, the others used as slaves.

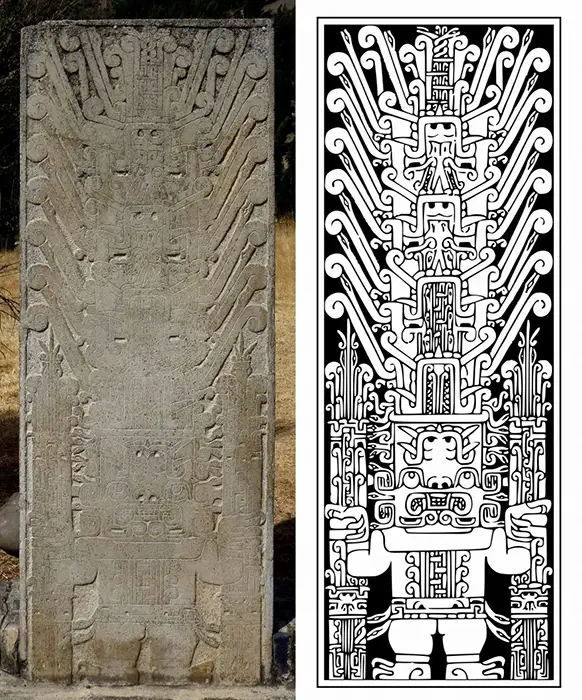

A historical example of the sacrifice of a prestigious enemy, mentioned in the engravings of Stele 2 of Aguapietra, is the case of "Jaguar's Claw", ruler of Seibal, captured by the armies of the lord of Dos Pilas known as "Sun Jaguar", after the battle between the kingdoms of Dos Pilas and Seibal between the 12th and XNUMXth centuries. AD "Jaguar's claw" was kept alive for XNUMX years before being sacrificed after a particular conjunction of Venus; on this occasion a decisive one would also have been relevant game of pok to tok. This was an ancient board game that took the name of pok a tok by the Maya, of tlacthli or ilatchli by the Aztecs and later called pelota, based on the throwing of a rubber ball inside a special sphere, with references symbolic to astral motions (in particular the cycles of Venus, and especially of the Sun among the Aztecs) and often culminating in a final sacrifice, probably perpetrated on the loser.

Widespread in almost all Mesoamerican cultures, it seems that already the ancient Olmecs practiced this particular and important "sport" which, like everything concerning the world view of a traditional people, was obviously awarded with precise and profound ritual symbolism. In fact, as the main point of connection between the human world and the upper world was of course the temple, the game of pok a tok was played in a special space (an H-shaped playing field) which symbolized the cosmos, and the participants assumed the roles of the primal gods in connection with cosmic energies.

An important and precise representation of the preparations for human sacrifice can be found in the beautiful murals of the temple of Bonampak, in Chiapas; a fresco in the second room shows the presentation of the prisoners to the ruler of Bonampak, Chaan Muan. The lord is depicted on a platform, adorned with colored feathers, jade jewelry and jaguar skins, a symbol of great warrior valor. The sovereign is surrounded by various dignitaries and, at his feet, the prisoners are placed in an act of submission and prepared to be sacrificed. Another common practice mostly in the postclassic period was the sacrifice in the seat of the so-called cenote (tzonoot in ancient Maya, "sacred well"), a ritual act typically connected to the agricultural cycle7 and the rains, making sacrifices aimed at the god Chac.

Theater of human sacrifices perhaps less bloody than those that took place on the stairways of the great temples, the cenote were large natural cavities filled with rainwater into which the chosen ones were thrown, often virgin maidens but also men. The large supplies of water were essential in periods of drought, considered a blessing from the god Chac to whom the sacrifices were directed as thanks or invocation. The largest and most famous is probably the cenote at Chichen Itzà.

As for the arrangements self-sacrifice for evident ascetic ends, a case of this kind is illustrated in the so-called relief of the Lady Xoc, near Yaxchilàn, dating back to about 709 AD. The image illustrates a type of sacrificial rite perhaps dating back to the Olmecs themselves, consisting in the loss of large quantities of blood through a hole in the tongue. It is relevant that the image depicts a woman of noble lineage (as evidenced by the jewelry worn, the hairstyle and the feathered headdress), since it seems that the tradition of sacrificial self-mutilation was characteristic of the nobles and the powerful and took place in presence of musicians and dancers, as well as prior the intake of psychotropic substances such as peyotl, all elements that favored a hallucinatory state necessary for probable initiatory purposes.

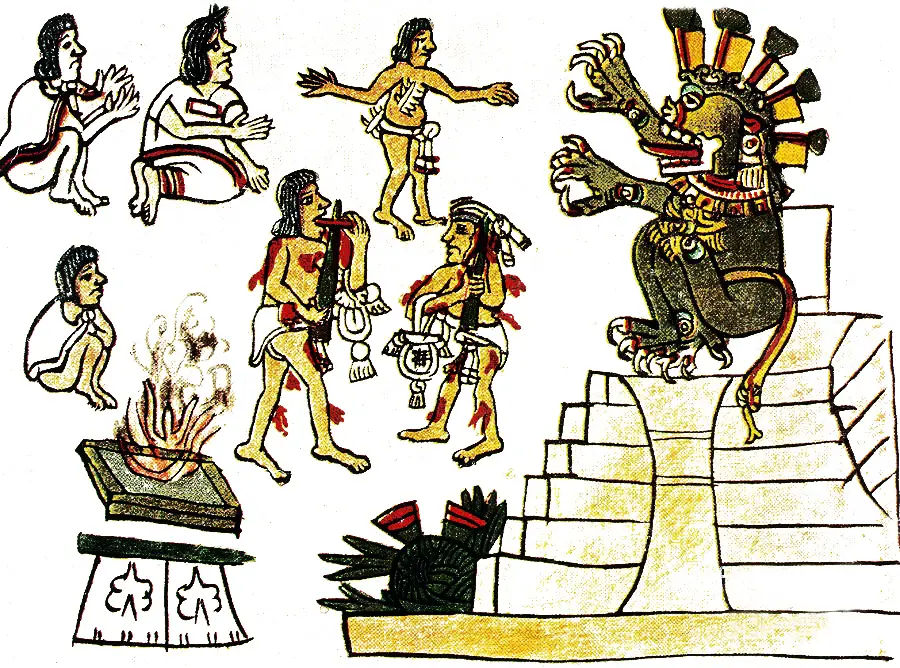

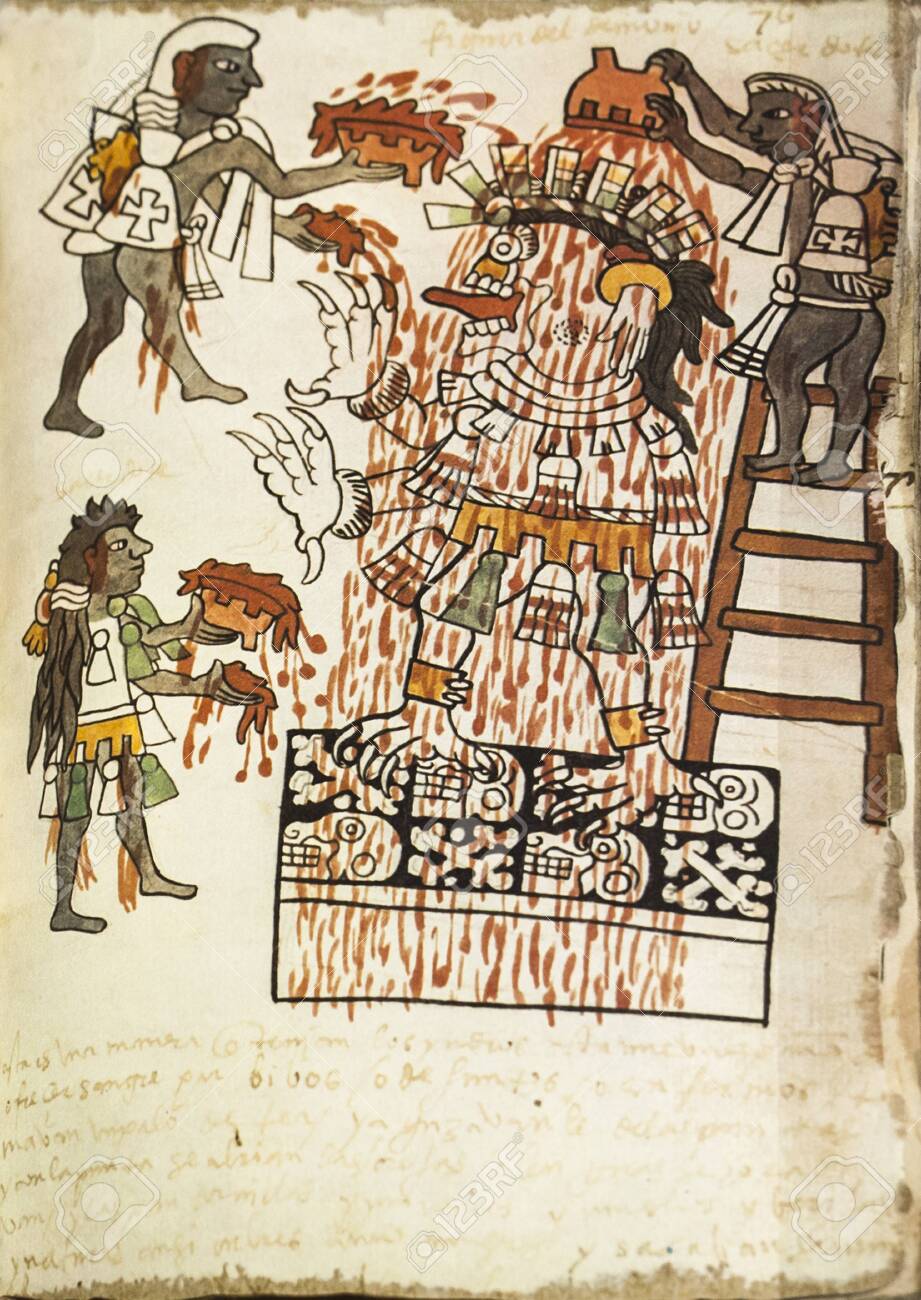

Basically, the direct sources we have on the civilization of the Aztecs or Mexica are those provided by the so-called codices, ie numerous texts engraved on amatl paper, contemporary and mostly after the Spanish conquest. Among these are the famous Codex Borgia, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Codex Borbonicus and hindquarters Codex Ramirez (also known as Codex Tovar or Relación del origen de los indios que hábitan esta Nueva España según sus Historias, attributed to Juan de Tovar), and the Codex Huexotzinco, contemporary to the invasion of the men of Cortés who will besiege Tenochtitlán in 1521 (moreover assisted by local contingents such as the Tlaxtalan warriors, historical enemy people of the Aztecs against whom it advocated a forty-year resistance) putting an end to the empire of Montezuma II.

Very important for information on Aztec religion and mythology is above all the Historia General de las cosas de la Nueva España written by the Franciscan Bernardino of Sahagún at the time of the Spanish conquest and published in 1569. The first Aztec settlements in the valley of Mexico date back only to the middle of the XNUMXth century. The people were organized as a warrior society with egalitarian traits, essentially made up of soldiers and peasants, in which the priests of the ancient cult of the god Uitzilopochtli.

According to the myth, the Aztec people came from Chicomòztloc, the "place of the 7 caves" placed to the north, or from another northern land, the mythical island of Aztlán (which suggested a distant "Atlantean" origin, according to traditionalist currents of thought) and, again according to tradition, the conquest of the new lands would have been consecrated by the observation of a particular omen: the fight between an eagle and a snake, which inspired a significant image of the Codex Mendoza (a text that made a great contribution to the deciphering of the Aztec pictographic script).

It is interesting to observe how, notoriously, even in the tradition of the classical civilizations of the old continent these animals assumed symbolic roles full of meaning (as well as being recalled in the Zarathustra by Nietzsche). The image ofeagle it comes in fact assumed by the Aztec empire as an emblem of its military glory (singular coincidence, in fact, with the warrior banner of Rome and with the symbolism linked to the Hellenic Zeus), thus having a cultural importance comparable only to that of the jaguar. Even in Aztec culture, characteristics such as valor, strength, prestige and power were associated with the name of the feline (called ocelotl) by kings, warriors and priests, as well as, it was handed down, by the gods themselves.

The relevance and antiquity of this symbol are also testified by the mythological tradition, which he saw the primordial cosmic era rising around Ocelot-tonaituh, the first "Sun-jaguar". Notable fighters and rulers, the Aztecs in turn assimilated many traits of previous cultures, however, grafting into them a particular mystical-warrior sense (already in keeping with the Toltec tradition, being Tula ruled by the military caste); in less than two centuries, after numerous battles with the neighboring peoples and a troubled political rise, the old nomadic group became masters of Mexico, conquering important political and religious centers such as Tula and Teotihuacán. To seal this was the construction in 1345 of Tenochtitlán, the great capital of the Fifth Sun risen on the waters of Lake Texcoco.

In the perpetration of institutions and customs of ancient peoples, the Aztecs practice the cult of Kukulcan / Quetzalcoatl and various other deities of Mixtec, Toltec or Mayan origin, as well as observing the traditional ritual calendar, partly adapted. At the new state civilization the calendar took the name of tonalpouhalli, of which there is the most famous representation in the magnificent "Stone of the Sun", the twenty-ton basalt monolith dating back to the XNUMXth century preserved in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. The tonalpouhalli computed a 260-day year divided into twenty thirteen-day series; each twenty-day month was given a specific "sign" such as cipactli (crocodile), ozomatli (monkey), eecatl (wind) and so on, and each 20-day month was also "dominated" by the sign of its first day, which established whether the month would be pompous or disastrous.

As per tradition, various forms of sacrifice were practiced on the occasion of the numerous festivities sanctioned by the calendar. For the Aztecs, while the warriors who fell in battle became companions of the Sun in the eastern region of Tlalocan, as well as drowned dead and women who died in childbirth (a form of death considered equally heroic, as the woman died fulfilling her natural and noble mission), prisoners of war were usually the chosen victims for sacrifices. Not by chance, the term for "sacrificial death" was huitzilopochtli, and the same word identified the name of the solar god of war, chief of the ancient nomadic tribes, hypostasis of the midday sun and patron deity of Tenochtitlán.

Il myth of Uitzilopochtili ("Southern hummingbird"), probably of Toltec origin, he describes this important divinity as a human, however possessing the exceptional characteristics of a warrior and shaman; according to some versions he was the son of the original androgynous god Ometeotl, according to others of the goddess of the Earth Cotlicue or, again, of a priestess of the aforementioned goddess. The archetypal characteristics of Uitzilopochtili are those of the fighter and the civilizing hero: he was born in fact already armed with darts and a shield on Mount Coatpec, in the Tula region, on the day of the Winter Solstice (similarly to Quetzalcoatl).

Similarly to the figures of Itzamna among the Maya and of Kukulcan in the Toltec culture, Uitzilopochtili acts pioneeringly exterminating with his turquoise knife the four hundred «southern brothers», the stars of the South, and sister Coyolxauhqui, goddess of darkness. Protector of warriors, according to the Uitzilopochtili tradition he would have been the instigator of the cult of the jaguar and of human sacrifices. Connected to Uitzilopochtili, the war sphere and the tradition of human sacrifice is the cult of Tezcatlipoca, astral god of Ursa Major and of the night sky, who, according to the Toltec myth, had driven out Quetzalcoatl from Tula (a reference to the cosmic cycle of the phases of Venus).

Even that of Tezcatlipoca is a figure with decidedly "martial" features, but his role is above all that of divinity guarantor of order and justice: called the "Smoking mirror", he was depicted equipped with gold mirrors through which he observed and judged the actions of men. Even the figures of the two main deities are therefore connected, in the Aztec religious conception, to thetraditional Mesoamerican idea that the Sun. (as well as water, earth and the gods themselves), to live and thrive while guaranteeing life for the world, it had to be regularly fed with human blood, a concept that precisely among the Aztecs became of absolute importance, if not strictly obsessive.

Raffaele Pettazzoni (Introduction to the history of religions, 1965) indicates this conception of sacrifice when speaking of "Sacrifice-gift", based on the killing of the victim who serves as nutrition for the deities (or, no less frequently, for other types of superhuman beings, such as mythical ancestors) who otherwise would suffer. By entering into a pact with the divinity in this way, the sacrificers secure his benevolence through the sacrificed. The act can also have the further meaning of "Sacrifice-communion" with the superior entity, for example when the victim is conceived as identical or assimilated to divinity: we can recall the cases of classical Greece with the killing of the fawns sacred to Artemis and of the Dionysian homophagy, in which the goat sacrificed and eaten raw had to repeat the fate of Dionysus as a child, mauled and devoured.

In traditional Mexico there is in this sense a sacrifice such as that practiced in the Aztec ceremony of the Tlacaxipeualitzchli (see below). Coming from the East (Aztec Acatl), from the heavenly realm of tropical abundance under the protection of Tlaloc, the ancient god of rain and winds among the Teotihuacans, the Sun was seen by the Aztecs as a hypostasis of Uitzilopochtili which every year had to regenerate itself through the blood of sacrifices, in a typical relationship of identity between the human world and the Uranian regions.

It must also be taken into account that the climatic and geological conditions of the valley of Mexico were characterized by frequent natural disasters: in the chronicles of Aztec history the memory of a violent hurricane dating back to 1464, of an epidemic in 1480 and subsequent, long periods of great drought. A state of affairs that could only systematically foment, among the people, the ancestral terror for the end of the Fifth Sun. If the great star had not been nourished, he would not have had the energy to resurrect, interrupting his natural cycle and thus putting the universe in grave danger.

Extremely important in this regard was the celebration of the so-called "Binding of the years" or the "New Fire", carried out for the first time according to tradition in the XNUMXth century on the mountain of Coatpec, and foreseen by the tonalpouhalli every 52 years. It was on this day that the terror for the possible end of the Sun particularly crept into the people, at the end of a year which began on 1 cipactli and ended on 13 xochtil. The ceremony, certainly one of the most evocative and significant spectacles in the Aztec world, featured one collective extinguishing of all fires in the Tenochtitlán area. The city thus plunged into total darkness while on the top of Mount Uixcachtecatl the priests, observing the motions of Pleiades, they lit the only fire visible for miles on the chest of a sacrificed prisoner, with methods that involved the use of the magic staff called tlequauitl. If the rite was successful, the messengers reported in the city that the world had resumed its regular cycle for another 52 years.

As we have seen, the sacrificial rite was often and mainly practiced on prisoners captured in battles, who assumed the role of tlatlacotin, incorrectly translated as "slaves" but actually indicating people who are not free and obliged to perform a function aimed at the service of the community. The heroic death of the condemned could also take place in the form of the so-called tlahuicole. This is how this type of sacrifice was called from the name of Tlahuicolli, a Tlaxcalan nobleman captured by the men of Montezuma II and of whom he refused the grace granted to him, which took place in the form of a gladiatorial battle with white weapon reserved for the most valiant enemies, of which they measured themselves their competitive skills in deadly combat.

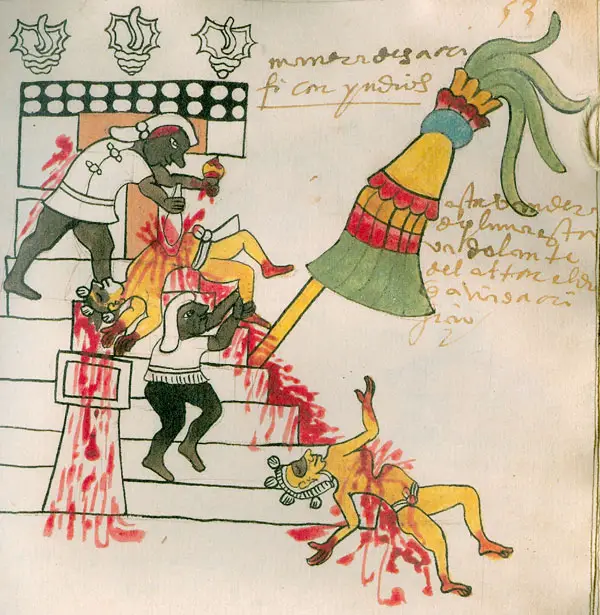

But not only that: the victims killed on the occasion of the great festive celebrations were often also chosen among women and children belonging to the same Aztec people. The principal administrators of the religious cult, assisted and directed by the priestess called "snake woman", were the two high priests of Uitzilopochtili and Tlaloc; the main building of worship, the great temple of Tenochtitlàn, called Teocalli, dedicated to the two gods. Often even the emperor (or the Tlatoani, "the one who commands" or "the one who speaks", the name of the ancient military command post) did not shy away from personally killing victims on the top of the temple. The sacrificial victims were usually harnessed with the particular vestments attributed to the gods of the respective festivities, in order to faithfully represent the death and resurrection of the aforementioned. This was the case with ceremonies such as those of Tlacaxipeualitzli and Teotleclo. Teotleclo, the "return of the gods" dedicated to Tezcatlipoca, was celebrated between autumn and winter (the ceremony represented the path traveled by the Sun during the year, its temporary "death" at the zenith and its future rebirth).

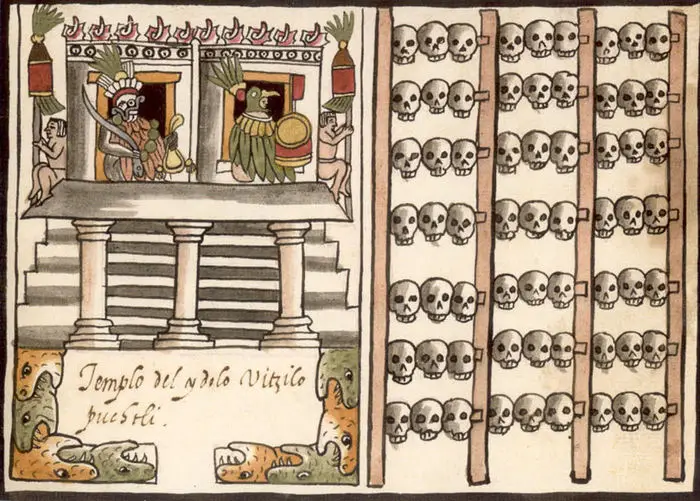

The most worthy prisoner of war was chosen to impersonate the god; for a whole year he was honored as a king, covered with the ornaments of Tezcatlipoca and could have as many as four women and a small personal entourage. On the agreed day, he was taken to the top of the temple of Tenochtitlan, grabbed by four priests and placed on a sacrificial stone slab. The heart was ripped off, and the head severed, after being rolled down the western stairway (evident reference to the descent of the Sun at sunset), was then placed in the special tzompantli of the temple. This was a type of wooden frame documented in several Mesoamerican cultures, which was used for the public display of the human skulls of sacrificial victims.

The practice of beheading seems to have been in vogue, according to the typically Mesoamerican and South American custom, as a reflection of the concept of a total appropriation of the victim's vital energy. This idea of the skull as the seat of individual power it would be found as early as the Olmec period (considering the characteristic lithic sculptures in the shape of gigantic heads, found in the site of La Venta and San Lorenzo and dating back to the XNUMXst millennium BC); the same concept returns in Mayan culture as can be seen in Bonampak's frescoes, in the depiction of a defeated prisoner held by the hair by a military leader, up to indigenous cultures of the Brazilian Caxinauà, the Uitoto spread between Peru and Colombia and the Ecuadorian Jivaros (among which the practice of tanning the decapitated skull called tzantza, a term with a singular assonance with the Aztec tzompantli is characteristic).

Aztec women were sacrificed in rituals aimed at propitiating the fertility of the earth. In sacrifices like these, women danced representing the goddesses of the earth, before being killed by the priests. This example shows how often Aztec rites took the form of pantomime, accompanied by sacred music (similarly to what happened among the Maya). Even the festivity with the programmatic name of Tlacaxipeualitzli was a particularly macabre meaning of this type of ritual. The name of the celebration means indeed "Flaying of men", the feast of the god Xipe Totec (the "flayed Lord", a divinity of Mixtec origin that the Aztecs adopt as another manifestation of Tezcatlipoca), on the occasion of the spring equinox.

The custom was of dressing the chosen victims with the skins of killed prisoners of war, before they underwent the removal of the heart. The symbolism of the skinning referred to the ripening of the corn seed, which loses the external rind to germinate; likewise, Xipe Totec had flayed himself to feed humanity. Obviously it was essential, in the office of the rites, that the smallest details were respected; numerous observances had to be taken into account in the celebration, such as fasting, sexual abstinence and food taboos. Punishments such as fines or corporal penances were provided for officiants who did not act correctly.

Sacrifices often followed episodes of ritual cannibalism, a custom particularly in vogue in the late Aztec Empire, when sacrificial killings became a collective and state level practice of which an indicative case remains the inauguration of the temple of Tenochtitlán, when, according to different sources, ten thousand or even twenty thousand enemy prisoners would have been slaughtered. In the vision of modern Europe, a practice such as that of mass sacrifices in a rather brutal manner (the anecdote of the courses of human flesh, or "Food of the gods", offered to the men of Cortés as a sign of respect and hospitality) could only be misunderstood and condemned, and even greater is the perplexity that can arise, to modern eyes, in the face of the clear and irreconcilable contrasts that seem to characterize the ancient Aztec culture .

This dualism emerges evident in considering, on the one hand, the undeniable mass atrocities committed in the sacrificial sphere and on the other works such as the graceful sculptures representing the god Xochipilli, symbol of youth, music and games, or in scrolling famous passages of the ancient Nahuatl lyric, diversified into numerous genres such as the "war songs", the "flowery songs" or the religious songs called teocuicatl. Attributed to authors such as priests and sovereigns, it emerges from certain poetic production a dreamy and melancholy vein that longs for the mythical kingdoms of the gods and laments the finitude of human life.

But precisely from an analysis in a traditionalist key one could deduce the reasons forexasperation of the sacrificial rites that characterized the decline of the Aztec civilization, a phenomenon that occurred in a similar way in the final period of the Maya world. It has been emphasized, for example in the famous Revolt against the modern world of Evola, as at the time of the Spanish conquest the Mexican civilization was now decayed in a "sinister Dionysus" in which the theme of sacred war and heroic death was now confused and almost outclassed by the frenzy of mass sacrifices, in a systematic destruction of life as a desperate attempt to maintain contact with the Divine (also fomented, as we have said, by extremely difficult environmental conditions).

The lifestyle in which the Aztec empire poured in the sixteenth century, therefore, would testify that the great Mexican tradition had already been on its descending slope for some time, shortly before the tragic epilogue it met at the hands of the Spanish invaders. Which, by the cruel irony of fate, however, came welcomed into the lands of Montezuma just as Quetzalcoatl's emissaries, returning from his ancient exile beyond the great eastern sea. Correspondences in the practice of human sacrifice within the solar (and lunar) cults of the traditional cultures of Peru.

Even from a superficial view, it is evident that in the mythological traditions ofSouth America figures and events similar to those handed down by Mexican and North American cultures recur. This is the case with the creative gods or civilizing heroes, as well as the memory of previous cosmic eras (which, moreover, naturally refers to the immense question of the undeniable affinities, with the due differences, found in the Indo-European context in the doctrine of the Hindu Yugas and in that of the cyclical ages of the world in the Hellenic and Norse tradition) and of human races destroyed before the creation of the present one, traces of which can be found, for example, in the mythology of the Caribs of Guyana.

Particularly significant and recurrent in this sense is the myth of the flood, handed down to the Incas and present in Mesoamerican mythology: as mentioned, a universal flood would in fact have sanctioned the end of the Sun and the previous world according to the Mayan and Aztec tradition, and the same myth returns, with obvious and peculiar variations, to the Brazilian Caxinauà. Still, too in the mythology of archaic Peru the most important rites of cosmic regeneration are carried out in the celestial vault by what were considered the three main stars, namely the Sun, Moon and Venus, whose observation was attributed an importance similar to that found in the cultures of Mesoamerica.

It is therefore not surprising to note among the most ancient peoples of the Andean areas, who over the centuries founded a series of organized state civilizations (later subjected to the supremacy and cultural hegemony of the Inca empire), the custom of sacrificial rites with characteristics and modalities similar to those of Mesoamerican cultures. For example, similarly to deities such as Quetzalcoatl and Uitzilopochtili, also an important figure in Peruvian mythology such as the solar god Inti it is a cosmic hypostasis that must travel through the nocturnal and chthonic world, die through a self-sacrifice and then be reborn to a new identity by recovering its role in the cosmos. The same solar symbolism of death and rebirth was assimilated to the divinity in the form of a jaguar that was revered by the ancient Andean culture of Chavìn de Huàntar, a civilization that developed in the central Andes between 1200 and 400 BC.

5 comments on “The "blood of the Sun": on human sacrifice in the pre-Columbian tradition"