The mythologem of "cosmic weariness" and "earth suffering", which inevitably follows a divine action aimed at depopulating the planet - whether it be a war between gods or a deluge sent from heaven - to balance its irremediably compromised equilibrium, is finds with notable correspondences in different Indo-European traditions, or rather Indo-Mediterranean ones: in India and Iran as well as in ancient Greece, and partly also in the Old Testament tradition.

di Rosa Ronzitti

(Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference of Sanskrit Studies, Biella October 15, 1999)

article originally posted on the profile I Academia.e by the Author and subsequently republished on Heretics Mind

cover: illustration of the Mahabharata

1. The reason for the "war of depopulation" it represents a case of Greek-Indian concordance that has long been known to scholars [1]: both the sagas of Troy and Thebes as much as the great clash between Pāṇḍava and Kaurava they were in fact motivated, sub specie divine, as interventions aimed at rebalancing the relationship between population and environment. Although in India this motif appears well developed only from Mahābhārata, then passing, with various adaptations, to the Purana, it was conveniently noted as the conception of a land (sop) carrying the weight of men and things is already well present in the R̥gveda (RV) and in Atharvaveda (AV) . Here the elements that weigh on the earth are "mountains" (RV V 84.1; AV-VI 17.3), "trees" (RVX 60.9; AVIV 26.5; VI 17.2), "men" (AV IV26.5; XII 1.15), " sacrificial columns "(RV X 18.12); the earth is also "the bearer of everything", viśvaṃbharāivali (AV XII 1.6). In these passages, the use of the root prevails bhar-, to be understood in the triple, pregnant meaning of "Carry, generate, bear". The differentiation sometimes identifiable in Vedic between "divine, animated land" (pr̥thivītil ) and "soil" (bhūtilmi-) [2] makes it possible for the earth to bear the weight of itself, as in RV VII 34.7:

úd asya śúṣmād bhānúr nāivalirta bíbharti bhārám pr̥thivīivali nà bhùma

“As a ray of sunshine [radiates], so [the sacrifice] radiates from its energy; bears the weight like the earth the soil ”.

In this room the endurance of the earth it is assumed as a topical element of simile, not unlike in AV VI 17, a spell to ward off abortion whose refrain it sounds:

yátheyám pr̥thivīwil mahīī dadhara…

evāivali te dhriyatāṃ gárbho ánu sū tastiuṃ sávitave"As this great earth firmly carries [the embryo, the trees, the mountains, the living beings], so your embryo remains firm [in the womb] after conception so that it can be born!".

The most interesting step, however, is offered by AV XII.I, the famous hymn in which the land, the dedicatee of the composition, is defined "patient" (str. 29):

vimḁ̃gvarīṃ pr̥thivīivalim āivali vadāmi / kṣamāivaliṃ bhūtilmiṃ bráhmaṇā vāvr̥dhānāwilm

"The pure earth I invoke, the patient soil, augmented by the sacred formula".

This is the first Old Indian attestation of the adjective kṣama- “patient, suffering”, corradicale of kṣam- “To suffer” (RV +). The mention of kṣamá- next to pr̥thivītil and bhūtilmi- reveals the will to find an etymology for kṣám- (name kṣāί), the Indo-European name for "earth", absent here but actually suggested by the union of the signifier kṣamātilm with the meanings of pr̥thivītil e bhūtilmi-. The "earth" therefore bears written in its own name (kṣám-) that "patient" attitude (kṣamá-) that characterizes her in the daily and eternal effort of (su) carrying the weight of all creatures. In the classical language, however, many substitute epithets of the name, such as dharaṇī, dharitrī, bhāratī, "The bearer", and the same kṣamā they refer to the task for which the earth was destined.

2. In the Mahābhārata the issue of the delicate balance between population and environment is central: the earth in person goes to the gods to ask to be relieved of the excessive weight of men, who have grown out of all proportion; the gods then promise her to unleash a bloody conflict that will depopulate the world. The well-known motif, which is already considered Indo-European if not even Indo-Mediterranean (see par. 6), has many implications in the epic and Puranic literature and is intertwined with the myth of the flood. The testimonies of the Mahābhārata they are many; one offers below sample significant places [3]:

to. I.58: The earth, thanks to the work of Rāma, thrives under the dharma. Men multiply, but also the Asuras, incarnated in the most diverse creatures, grow in number. The earth can no longer bear its own weight and goes to Brahmā asking to be relieved. Brahmā exhorts the gods to come down to earth and exterminate the Asuras;

b. III.42: Arjuna receives the rod from Yama (the god of death) with the task of lightening the earth;

c. III.141 (published by Bombay) [4]: Lomaśa tells Yudhiṣṭhira that Viṣṇu, in the form of a boar, brought the earth back to the surface, which had sunk into the ocean due to the weight of too many creatures that they had ceased to die because Yama, god of death, did not exercise his office;

d. III.186: Mārkaṇḍeya narrates that at the end of each kalpas moral and religious customs decay; too many men are born, a great flood is needed to purify the earth (however, no explicit reference is made to "suffering");

And. VII.52-54 (published by Bombay) [5], XII.248-250: Bhīṣma explains to Yudhiṣṭhira the origin of death. In the beginning Brahmā had to burn the creatures multiplied in excess because the earth itself, oppressed by their weight, told him that it was afraid of sinking.; later the god solved every problem by creating death, a beautiful woman whose tears of compassion towards living beings generate misfortunes and diseases;

f. XI.8: Vyāsa consoles Dhr̥tarāṣṭra, prostrated by the war and the extermination of his children, explaining to him that this happens out of a greater necessity: the earth has asked to be relieved of the weight of men;

g. XII.202: Viṣṇu, incarnating as a boar, saves the land oppressed by the Asuras and the Dānavas.

From the numerous references contained in the poem it appears that the lightening of the earth is not only a contingent motivation for the war in progress on the plain of Kuru: it was repeated at the beginning of time, in the mythical age called Kr̥ta (passage c) or when again death did not exist and Brahmā had to create it not out of hatred towards creatures but out of the need to free the world (And). The inevitability of death is a consolation argument for King Anukampaka, unable to accept the disappearance of his son (e), and for Dhr̥tarāṣṭra (f), who, only after listening to the wise words of Vyāsa, is able to inscribe the his own misfortune in a larger cosmic plane that pain prevented him from recognizing:

mahatā śokajālena praṇunno 'smidvijottama / nātmānam avabudhyāmi muhyamāno muhurmuhuḥ

“I am driven [to speak like this] by the great pain trap [6], O supreme of twice-born beings! Being always confused, I don't perceive myself! " (XI.8.46).

In some versions of the myth the earth manifests the fear of "sinking" into ocean waters:

iyaṃ hi māṃ sadā devī bhārārtā samacodayat / saṃhārārthaṃ mahādeva bhāreṇāpsu nimajjati

"The goddess earth, continually afflicted by the weight [of creatures], pushed me, O Mahādeva, to destroy them, because due to the weight she seemed to sink into the waters" (XII.249.4) [7];

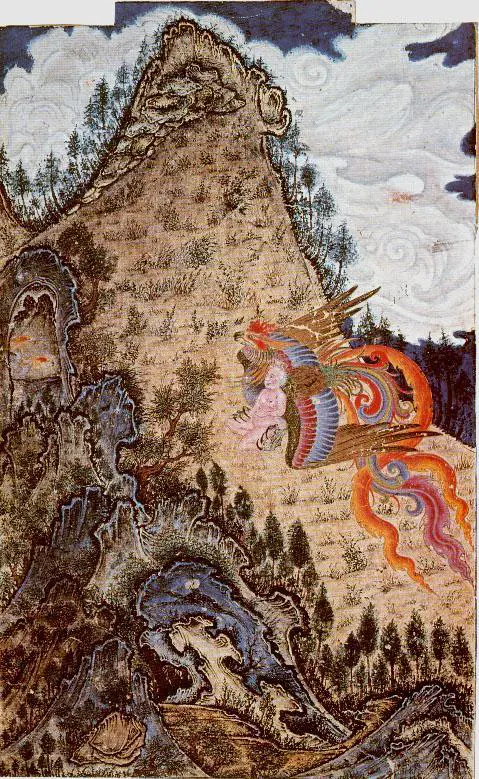

or it sinks and, from the oceanic abyss, is forced to ask for the help of Viṣṇu, who, assuming theavatara wild boar (varāhāvatāra) [8], descends to the ocean floor to save her by bringing her back to the surface [9]:

idaṃ dvitīyam aparaṃ viṣṇoḥ karma prakāśate / naṣṭā vasumatī kr̥tsnā pātāle caiva majjitā / punar uddhāritā tena vārāhenaikaśr̥ṅgiṇā /

“Here too we see another fact of Viṣṇu. Once the earth, having been lost and having sunk in the lower regions, was brought back to the surface by him, which had the shape of a boar with only one horn "(III.141. Rr. 56-57) [10].

The reader who is just an expert in Sanskrit things will not be able to fail to identify some points of contact between our myth and that, very famous, of the flood [11], which right in the Vain Parvan knows one of its oldest and most extensive versions (the one shown in d): as the overpopulation of the earth, so the flood is a catastrophe that cyclically marks the end of every great cosmic epoch, a sort of gigantic cleaning work necessary for the regeneration of the universe; like overpopulation, the flood is also an inevitable event, devoid of ethical reasons, even if preceded by signs of decay and corruption. At the end of each kalpas, in fact tells the Vain Parvan, the world appears upside down: the Brahmans neglect their studies, the servants study the Vedas, the wicked rule the earth. The population is growing excessively: women have too many children and too early. A great drought begins to pervade the earth and, soon after, a flood lasting twelve years engulfs it. Only one man survives, Manu (the Indian Noah), who, thanks to the guidance of a fish (later revealed to be Brahmā), brings the ark [12] to the top of the Himālaya.

3. A second point of contact between the two myths is attested in Puranic versions of the deluge, where it appears that the reason why the earth has sunk into the waters is not that of the multiplication of creatures (as in the passage just quoted from Mbh III.141), but the flood itself. Let's think of the long "speech" of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa (III.13), in which Manu asks Brahma to re-emerge the earth and the supreme creator sends the boar (Viṣṇu) to bring it back to the surface on the tip of his horn. In the Matsya Purana, then, the fish-Viṣṇu shows Manu a ship destined to host and preserve from the flood the four species of living beings, born from sweat, from the egg, from the shoot and from the placenta. According to Paolo Magnone's convincing interpretation, this ship is the earth itself. It is said in fact in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa that Viṣṇu, during the flood, assumed the shape of a fish and saved Manu by making him get on a "telluric ship" (naur mahimayi, I.3.15). The Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa, then, narrates that the earth, personified in the goddess Satī, became a ship and carried with it the seeds of all things, escaping the flood unleashed by Śiva (1.75.9-10). Rightly, therefore, Magnone concludes that "The ship is not a simple human artifact, the ship is the earth itself in its' diluvial form".

We wonder if the epic and puranic traditions do not unravel an already ancient intertwining, which they contained in nuce the threads of the two myths: that of overpopulation and that of the flood. Think of the beautiful Rigvedic simile that relates the earth to a loaded and vacillating ship to the impetuous breath of the winds, see V 59.2ab:

ámād eṣām bhiyás ābhū tasti ejati naúr ná pūrṇāivali kṣarati vyáthir yatīivali

"By the impetus of those [the Maruts], by fear the earth shakes, it slips like a loaded ship that goes tottering."

"Like a ship" is an expression destined to repeat itself in later literature; cf. Viṣṇu Purāṇa (I.4.45-46):

evaṃ saṃstūyamāno 'tha paramātmā mahīdharaḥ / ujjahāra kṣitiṃ kṣipraṃ nyastavāṃś ca mahārṇave // tasyopari samudrasya mahatī naur iva sthitā / vitatatvāc ca dehasya na mahī yāti samplavam

“The supreme being, sustainer of the earth, thus praised, quickly lifted it up and placed it on the great ocean; on the top of the sea it floats like a mighty ship and thanks to its vast surface it does not sink under the waters ",

and still it scanda (II.2.3.9):

ekārṇave mahāghore naur iva kṣetram īkṣyate

“On the one, formidable wave [13] the earth looks like a ship " [14].

3.1. In the variant of the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa cited above, the goddess Satī, wife of Śiva and personification of the earth, contains within herself the seeds of all things. The generative value implicit in this narrative (the earth is preparing to give life, after the flood, to creatures) is certainly also present in the episode of varāhāvatāra: in contact with the wild boar's tusk, the soil full of water is fertilized [15]. Again, there is no lack of points in common with the alleviation myth: according to the version of the Kālikā Purāṇa, in fact, the earth, assuming the appearance of a graceful wild boar, flirted with Viṣṇu for a long time (chapters XXX and XXXl) [16]. From love three wild boars were born, but the earth and the entire universe could no longer bear the weight of Viṣṇu: the earth began to crack in the middle, shaken by the blows of the boar's hooves. The gods then ran to beg Viṣṇu not to oppress his wife again. Not the weight of men, but the weight of the god (that is, his sexual energy) contributes this time to disturb the cosmic balance.

4. The striking similarity between the schooled to Iliadem The 5 and the steps of the Mahābhārata for a long time it has attracted the attention of scholars with a view to the reconstruction of an Indo-European and Indo-Mediterranean culture. The Greek texts highlight the similarities and differences between the Hellenic and Indian traditions. The most ancient testimony (VII century BC) is notoriously theincipits of the Face powder, preserved by the Homeric scholiasta in commentary by Il. I 5. Explaining the meaning of the expression Διὸς δ᾽ἐτελείετο βουλή "the will of Zeus was fulfilled" (which is preceded by the reference to the merciless end of many heroes on the battlefield), the scolium of Venice A tells that the will of Zeus consisted in the decision to relieve the earth:

ἄλλοι δὲ απὸ ἱστορίας τινὸς εἶπον εἰρηκέναι τὸν Ὅμηρον· φασὶγὰρ τὴνΓῆν βαρουμένην υπὸἀνθρώπων πολυπληθείας, μηδεμιᾶς ἀνθρώπων οὔσης εὐσεβείας, αἰτῆσαι τὸν Δία κουφισθῆναι τοῦ ἄχθους· τὸνδὲΔία, πρῶτον μὲν εὐθὺς ποιῆσαι τὸνΘηβαϊκὸν πόλεμον, δι᾽οὗ πολλοὺς πάνυ ἀπώλεσεν. ὕστερον δὲ πάλιν - συμβούλωι τῶι Μώμωι χρησάμενος. ἣν Διὸς βουλὴν Ὅμηρός φησιν – ἐπειδὴ οἷός τε ἦν κεραυνοῖς ἢ κατακλυσμοῖς πάντας διαφθείραι, ὅπερ τοῦ Μώμου κωλύσαντος, ὑποθεμένου δὲ αὐτῶι γνώμας δύο, τὴνΘέτιδος θνητόγαμίαν, καὶθυγατρὸς καλὴνγένναν, ἐξ ὧν ἀμφοτέρων πόλεμος Ἕλλησί τε καὶ Βαρβάροις ἐγένετο, ἀφ᾽οὗ συνέβη κουφισθῆναι τὴνΓήν, πολλῶν ἀναιρεθέντων. ἡ δὲ ἱστορία παρὰΣτασίνωι ·

ἦν ὅτε μύρια φῦλα κατὰ χθόνα πλαζόμενα᾽ αἰεὶ

<ἀνθρώπων ἐπίεζε> βαρυστέρνου πλάτος αἴης,

Ζεὺς δὲ ἰδὼν ἐλέησε καὶ ἐν πυκιναῖς πραπίδεσσι

κουφίσαι ἀνθρώπων παμβώτορα σύνθετο γαῖαν,

ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο,

ὄφρα κενώσειεν θανάτωι βάρος. οἱ δ᾽ἐνὶ Τροίηι

ἡρωες κτείνοντο, Διὸς δ᾽ἐτελείετο βουλή“Others maintain that Homer said (this) following some tale: in fact they say that the earth, being weighed down by the multitude of men and not harboring any religious sentiment among men, asked Zeus to be relieved of the weight: Zeus immediately unleashed the war of Thebes, through which he killed many. Then again, using Momo as an advisor (which Homer calls "the will of Zeus"), he could destroy everyone with lightning or flooding. But Momo prevented him and suggested two solutions: Thetis' marriage to a mortal and the beautiful progeny of her daughter [Elena]; and from both these things arose war for the Greeks and for the barbarians and from this it happened that the earth was lightened by the killing of many men. The story can be found at Stasino:

«When the multitudes of men who always wandered on the earth by the thousands oppressed the surface of the earth from the vast chest, Zeus, seeing it, took pity on it and in his shrewd mind decided to lighten the nurturing earth of all men by fomenting the great contest of the war of Ilium to lighten the burden with death. And the heroes who were in Troy were killed: Zeus' will was fulfilled »”.

Among the truly remarkable similarities of the Indian myth to the Greek one it should be noted that in both traditions the earth, a divinity rarely protagonist of personal initiatives, goes before the god (so in the scholiasta but not in the passage by Stasino, in where Zeus "sees" the suffering of the earth and intervenes), who is taken by compassion for her. However, the Greek tale also seems to give an ethical value to the reasons for the conflict: feet religious, and for this reason they deserve to be punished. Zeus's intervention is not direct, but mediated by two events: the wedding of Thetis and the birth of Helen. The marriage of Teti with a mortal generates Achilles, the hero who, with perfect consistency, calls himself ἐτώσιον ἄχθος ἀρούρης (XVIII 104): born to relieve the weight of the earth, he is himself a vain weight. The general condition of man is reflected in Achilles' personal bitterness, destined to burden the one who hosts him and allows him to live. This is particularly evident in the Euripidean Oreste, the richest in suggestion among the successive re-enactments of the myth, cf. i vv. 1641-1642 (Apollo motivates the Trojan War):

θανάτους τ᾽ἔθηκαν, ὡς ἀπαντλοῖεν χθονὸς

ὕβρισμα θνητῶν ἀφθόνου πληρώματος"[The gods] wanted deaths to eliminate from the earth the outrage of the immeasurable number of mortals".

The choice of the word ὕβρισμα "Outrage" is shown in all its significance if we remember that ὕβρισμα e abound "To oppress" are probably corradical, and therefore an etymological will is underlying the passage: the "weight" of men has turned into outrage, their overcrowding offends the earth. But even more surprising and certainly tempting for a comparison is the word with which the poet expresses the action of "lightening": not the most usual κουφίζω [17], but rather ἀπαντλέω. It is a verb that contains the name of the "bilge", ἄντλος. It is therefore implicitly suggested that the action of relieving the land is equal to that of emptying a ship of bilge water: the ship (too) loaded with R̥gveda, the telluric ship of the gods Purana. Man, outrage and filth of the earth, must be eliminated by the one he threatens to sink.

5. If we just widen the narrow meshes of the features on which the Greek-Indian concordance is based, we can more broadly speak of a Greek-air concordance, as not even atAvesta the issue of overpopulation is foreign. The second one Fargard of the Vīdēvdād, entirely dedicated to the mythology of Yima (primordial man in many respects superimposable to Manu), shows the profound interest that the Iranian populations reserved for the lack of space for men and livestock, cf. II, 8-11 [18]:

"Three hundred winters passed under the reign of Yima, and the earth was filled with flocks, herds, men, dogs, birds and blazing fires and there was no more space. for the flocks, herds and men. Then I [Zarathustra] warned gentle Yima saying, 'O gentle Yima, the earth is filled with flocks, herds, men, dogs, birds and blazing fires and there is no more room for flocks, herds and men.' Then Yima walked into the light along the path leading to noon and struck the earth with the golden seal and pierced it with the dagger. [19] saying: 'Osanta Armaiti, open gently and lie down to bring flocks, herds and men!'. And Yima made the earth one third wider and behold flocks and herds of men came at his desire and pleasure because of the prolificacy of beings ”.

Two more times the earth is populated in excess and two more times Yima repeats the formula and the rite that allow him to extend it. (strr. 12-19). The increase in population, which in Indian texts appears as a cyclical and pernicious necessity, is here instead achieved by divine will. It is Ahura Mazda herself, in fact, who longs for a land teeming with beings. More and more numerous, men, livestock, birds and fires find their place thanks to a magical and non-bloody remedy for the shortage of space. The earth does not go, oppressed, before the gods; Indeed, it is Yima who kindly begs her to open up and relax.

Now, although in the Sanskrit language the earth is etymologically the "extended" (pr̥thivi), the act of its extension is above all a creative act that does not appear specifically aimed at providing new space for beings. In the beginning the earth was rolled out like a carpet and therefore, ipso facto, created [20], but not further extended with the growth of its inhabitants. Not even the myth of Emu, the wild boar that expanded the earth taking it from the size of a span to that of a habitable surface [21], appears to be aimed at a possible non-bloody reduction of overpopulation. This must undoubtedly be linked to the divinity's different attitude towards the problem: while the Indian (and Greek) gods perceive the multiplication of creatures as a threat to the ecological balance of the planet, in the Vīdēvdād it is Ahura Mazda herself who urges Yima to populate the earth and consequently provide him with the means to expand it peacefully. Is it possible that Indian culture has also known a similar strategy for solving the problem? We seem to be able to give a positive answer, catching a pale and isolated echo of the Avestan myth in RV I 52.11:

yád ín nv ìndra pr̥thivīivali dáśabhujir áhāni víśvā tatánanta kr̥ṣṭáyaḥ / átrāivaliha te maghavan víśrutaṃ sáho dyāivalim ánu śávasā barháṇā bhuvat

"When, O Indra, the earth was ten times larger and every day the peoples expanded, then your strength was truly known, O generous one, equal to heaven in energy and power."

Already Karl F. Geldner, in his commentary on R̥gveda, meant that Indra had associated the expansion of the Arian bloodlines with an expansion of the earth's surface and suggested in the footnote a possible comparison with the second chapter of Vīdēvdād Avestan. This same chapter also contains, immediately following the episode of overpopulation, the Iranian version of the flood, which, however, is not linked by any cause-effect relationship to the previous myth. Nor is there any mention of ethical motivations or divine punishments that unleash the destructive fury of the waters: as in Indian culture, the flood is an event that does not submit to any will. Ahura Mazda has only the task of alerting Yima to build a early ("Fence") to secure the seeds of mortals [22].

More similar to the biblical one is Ahura Mazda's attitude towards the population of the globe. The god of the Jews orders in fact to creatures to "be fruitful, multiply and populate the earth" (January. I, 22 and 28), but the comment of the midrash the passage does not fail to record the offended reaction of the earth: it goes to the creator complaining about the too much weight with which, inevitably, it will find itself loaded. The Bible also contains a reference to the necessity of death as a periodic renewal of the world: in January. VI, 3 Yahweh sets a maximum duration for man's life, which is rapidly populating the earth. Immediately afterwards, however, he realizes that man's wickedness is great and his thoughts are turned towards evil. Then follows the deluge, caused by that lack of eusebeia (the Greek scholium can be used here as a gloss) which perhaps is due to the excessive multiplication of creatures.

6. What an interpretation to give to the Greek-Indian concordances which, although not supported by a double correlation in terms of content and expression, show contents that are not only surprisingly similar, but also structured in such a way as to make an explanation in terms unsatisfactory. of "universal typological"? The concept of "weighing" is well rooted in Greek and Indian culture, but it is by no means exclusive to these or to the Indo-European peoples alone. A look that ranges from Eskimo to Amerindian beliefs, from Semites to Chinese, makes it clear how certain themes belong, without borders, to the human spirit. [23].

The "genealogical" solution is the one preferred by the Indo-Europeanists, but it cannot be excluded, for example, that the myth is an emergence, in distant areas, of a common substratum called "indomediterraneo" (according to the hypothesis of Vittore Pisani) [24] the result of a lively network of commercial (and therefore also linguistic and cultural) exchanges between populations prior to the advent in the historical sites of Semites and Indo-Europeans [25], or that both peoples drew from a common source. A study of Sumerian and Babylonian myths by specialists on the subject would probably lead to interesting results. For instance the Akkadian myth of Atramḫasīs (primordial man saved from the flood), from the Paleo-Babylonian period (1950-1530 ca. BC), it is largely centered on the problem of overpopulation and contains an explicit reference to the grievances of the land [26]. It is also possible (but less probable) to theorize a direct loan, the direction of which cannot be specified, between India and Greece: this loan will have been taken when it could still be incorporated into the epic tradition of the people who received it, not necessarily, therefore, in very ancient times. However, there does not seem to be any doubt about the antiquity of the motif itself.

Note:

[1] See R. Köhler, Rheinisches Museum NF 13 (1858), pp. 316-317; J. Hertel, Die Himmelstore im Veda und im Awesta, Leipzig 1924; V. Pisani, “The Indo-Mediterranean cultural unity prior to the advent of Semites and Indo-Europeans”, in Writings in honor of A. Trombetti, Milan 1936, pp. 199-213, reiss. in Languages and cultures, Brescia 1969, pp. 53-70, in part. pp. 64-65; Id., “Lndisch-griechische Beziehungen aus dem Mahābhārata”, Zeitschrift für die deutsche morgenländische Gesellschaft 103 (1953), pp. 126-139; W. Kullmann, “Ein vorhomerisches Motiv im Iliasproömium”, Philologus 99 (1955), pp. 167-192; H. Schwarzbaum, “Tue Overcrowded Earth”, Numen 4 (1957), pp. 59-71; P. Horsch, Die vedische Gāthā- und die ŚlokaLiteratur, Bem 1966, p. 264; G. Dumézil, Myth and Epic. La terra alleviata, Turin 1992 (Paris 1968), pp. 94-95 and 154; M. Durante, On the prehistory of the Greek poetic tradition, Rome 1976, vol. The P. 61, p. 29.

[2] See R. Ronzitti, “Observations on the names of the 'earth' in the R̥gveda and in the Atharvaveda”, Studi e Saggi Linguistici 35 (1995), pp. 45-115 and Ch. Orlandi, “The earth (RV. V, 84 and AV. XII, 1)”, in Scríbthair a ainm n-ogaim. Written in memory of Enrico Campanile, edited by R. Ambrosini et al., Pisa 1997, pp. 717-744

[3] The passages, unless otherwise specified, are cited according to the critical edition of Poona;

[4] The passage, of considerable interest, is removed from the Poona edition and included in the appendix;

[5] The passage, identical to XII.248-250, is removed from the critical edition of Poona;

[6] Literally “network of pain”: the polyvalence jālā- “network” and “illusion” is certainly used here to suggest to the reader that the pain felt by the king has no foundation but is only a deformation due to the anthropocentric vision of death;

[7] Speaking is Prajāpati, the supreme creator;

[8] On which cf. J. Gonda, Aspects of Early Visnuism, Utrecht 1969, pp. 129-145;

[9] See P. Magnone, “Avatāra. The descent of the gentleman ", Ab-stracta32 (dec. 1988), pp. 22-29. The avatāra frees the earth from its weight and ipso facto from the adharma, symbolized by the excessive weight of beings;

[10] An analogous episode is narrated in XII, 209: Viṣṇu incarnates himself in the boar and saves earth by descending, it would seem, into the underground infested by evil creatures. Di-defeats enemies with the force of its paralyzing grunts (see step g);

[11] See at least P. Magnone, “Matsyāvatāra. Indian scenarios of the flood ”, Proceedings of the Ninth National Conference of Sanskrit Studies (Genoa, 23-24 October 1997). Edited by Oscar Botto, edited by Saverio Sani, Pisa, 1999, pp. 125-136;

[12] The ship that leads Manu to salvation is already mentioned in the oldest known version of the Indian flood, Śatapatha BrāhmaṇaI.8.I.1-10;

[13] It is the wave of the primordial sea, which symbolizes the indistinct one in whose bosom all created forms have once again dissolved (cf. Magnone, Matsyāvatāra, cit.). See also the following note;

[14] To these passages it is necessary to add AV I.XII.59: yārsim anvaícchad dhavíṣā viśvākarmanāntár arṇavé rájasi práviṣṭām / bhujiṣyàm pāivaliṃ níhitaṃ gúhā yád āvír bhóge abhavan mātr̥mádvak was destined for the entry fluttan māyahuvak "which was the entrance to the fluttan nourishing vaklant with the fluttan ; she hidden in a secret place she became visible for delight to those who have mothers ”. Perhaps the image of the ship, container concave floating on water;

[15] So explicitly in the versions of the Viṣṇu (V.29.23-24) and of the Kālikā Purāṇa (XXIX);

[16] See W. O'Flaherty (ed.), Myths of Hinduism, Milan 1997 [1975], pp. 200-209 and 347;

[17] So in Hel. 36-41 (analogous re-enactment of the myth);

[18] The original text can be read in H. Reichelt, Avesta Reader; Berlin 1968 [Strassburg 1911], pp. 38-39;

[19] The two objects that had been delivered to Yima by Ahu-ra Mazda as symbols of royalty;

[20] See RV I 65.1; 103.2; II 15.2; V 87.7; VI 72.2; VIII 89.5; X 82.1; AV IV 26.1; XII 1.2;

[21] See Taittirīya Saṃhitā VII, l, 5,1. The wild boar was later assimilated to the varāhāvatāra of Viṣṇu, but in the texts preceding the Purāṇa it has its own autonomy (cf. Gonda, op. Cit., Pp. 134-139);

[22] In any case, it is an "earthy" enclosure, meticulously measured and delimited, which represents a portion of the ground destined to escape the flood;

[23] See Schwarzbaum, art. cit., passim .;

[24] Pisani, L'Unità, cit., Considers this myth one of the many Indo-Mediterranean cultural isoglosses;

[25] On the concept of "indomediterraneo" and its evolution starting from the Pisan writing of 1936 cf. D. Silvestri, The notion of indomediterraneo in historical linguistics, Naples 1974;

[26] 6 Cf. I vv. 354-359 of the text in the translation-interpretation by W. von Soden in AA. VV., Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments, Band III, Lieferung 4, Mythen und Epen II, Gütersloh 1994, p. 627.

3 comments on “The suffering of the earth: overpopulation and the myths of depopulation in India, Iran and Greece"