In the contemporary world the so-called "lake monsters", of which Loch Ness in Scotland is certainly the most famous, are the subject of study of the pseudo-scientific discipline called cryptozoology; but in the past it was the sphere of myth and folklore that was interested in these creatures, both in ancient Europe where legends about kelpies and similar entities are widespread, and in native America, which Michel Meurger rightly defines "the 'Eldorado of the aquatic monsters ».

di Francesco Cerofolini

La cryptozoology is that pseudoscience which, in the broad bed of "alternative realities", is concerned with studying and demonstrating the existence of creatures commonly considered fantastic as draghi, yetis and sea monsters. One of the favorite objects of study of this fantastic zoology are certainly the lake monsters, among which the best known is certainly the Loch Ness monster, whose fame exploded worldwide in 1933 and since then his figure has earned a prominent place in the modern monstrous imagery.

However, the Scottish lake is not the only one to host a monstrous tenant. In fact, there are dozens of bodies of water on every continent that local folklore indicates as inhabited by some type of monstrous creature. In many cases these are traditions created "ex novo" right on the wave of the notoriety of the Scottish monster, perhaps with the help of some local joker. However in many cases a closer analysis reveals how the modern legends about lake monsters are grafted onto a very ancient pre-existing folkloric and legendary fabric.

This aspect of the question was studied in depth by the Canadian folklorist Michel Meurger together with the university teacher Claude gagnon, who conducted a field survey at the beginning of the XNUMXs. Meurger's approach differed as much from that of cryptzoologists, determined to prove the physical existence of monsters, as well as from that of skeptics, who explained sightings and related beliefs in terms of misidentification of known phenomena. Meurger's research aimed to reconstruct the genealogy of beliefs about monsters and how they had evolved over time.

By gathering evidence at several Canadian and US lakes and scouring libraries for documents, Meurger traced back to the mythical and premodern origins of lake monster beliefs. The results of this went on to make up the dense study entitled Lake Monsters Traditions: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. In this article, which certainly does not pretend to be exhaustive, we will analyze the mythological roots of the tales of lake monsters, examining the Scottish lakes and the great lakes of Canada, trying to trace a connection between these myths and the modern cryptozoological foklore.

Meurger's investigation

Meurger's investigation examined several lakes which, according to local legends, were inhabited by monsters. In many cases, the rumors only spoke of specimens of known but exceptionally large fish, such as carp and pike. Many of the testimonies examined reported sightings of shapes similar to floating logs or mysterious "humps" emerging from the waters as in the case of Pohenegamook Lake, whose monster, nicknamed defeat, appeared as a large shape with a "of an overturned canoe».

But there were several eyewitness accounts that helped draw a more accurate portrait of the monsters that haunted North American lakes. In the Champlain Lake, famous for the monster Champ, a witness who saw the monster's head emerge from the water in July 1978 thus described his meeting "At first, the head appeared, like a horse head without ears, then a long neck came out of the water; it lasted less than a minute or two». Lake Pohenegamook was the scene of similar sightings. A resident on the shores of the lake told of having seen the monster Ponik on more than one occasion, claiming that he had initially mistaken it for "un horse lying in the water, near the shoreAsserting that, when observed better with binoculars, the strange being had a head similar to a cow and some rough hair on its long neck!

The image of an aquatic monster with equine characteristics is the prevailing one among the testimonies collected by Meurger. Paradigmatic in this sense are the accounts and legends collected at the Blue-Sea lake in Glatineau County. According to the inhabitants of the shores of the lake, an aquatic monster would live here too. A local fisherman reported to the researcher that the monster had been nicknamed Horse's Head, since it was a snake with a horse's head. Around 1913 he had been seen by a large number of people who had just come out of Sunday mass. He was black, around two meters tall and according to the elderly fisherman "It looked like a seahorse giant". "The people who came out of the church said, “Look at the big one beast! ”», Added the fisherman, and «caused a great, great wave. He came from a long way off. A man drowned three or four years later and was never found. People think that thing devoured him.»

Another elderly resident recalled his father's tales of the monster:

« My father has seen it many times. So does my uncle. When I was twelve or thirteen, around 1900 people saw him very often: it was the time when they were building the railway to Maniwaki. I saw him when I was nineteen, around 1910. I was fishing, I saw that thing behind me ... horse. »

It appeared however that Meurger had arrived late to hunt the monster because, according to the old man, the monster hadn't been seen for thirty years. For the resident elder the monster had moved to other lakes since annoyed by the growing presence of man. Other locals agreed with the elder: "In those days there were no motorboats ad annoy him», Reported an eyewitness, who among other things swore to have seen a mane on the neck of the monster.

During the investigation at Lake Blue-Sea Meurger came into contact with Louis Commanda, a member of the local Algonkin community, a Native American tribe. This meeting gave the opportunity to discover that for the natives the presence of the monster was well known:

« We call him Misiganebic, the Great Serpent. And the friend of the waters, the cleaner of the waves. He is been seen at Lake Désert, Lake Bitobi, Lake Pocknock, and the Gatineau River. It is said to be thirty feet long. The creature always appears in good weather and shines with all its colors »

According to Commanda's account, for the natives there is a Misiganebic in every lake. These creatures would spend the winter at the bottom of the lakes and seeing one would be a harbinger of death. Also according to the beliefs of the natives, the Misiganebic would have its abode in a cave "bottomless»On the shores of Lake Pocknock. Even at the time of the interview with Commanda, the presence of the monster was very much felt by the Alongkin, so much so that periodically, baskets full of food were placed in the lake, at the four cardinal points, as thanks to the Creator for the Misiganebic, the cleaner of the lake.

Meurger thus ascertained the widespread and deep-rooted belief in a mysterious aquatic animal with equine features. It is no coincidence that even more famous monsters like Ogopogo, the monster of the Okanagan lake, have been described as having a horse's head or in any case with sheep or equine features. Even the Loch Ness monster itself has been described on several occasions as having a mane on its long neck. Where did this strange animal come from? For Meurger, the answer was to be found in folklore and in the beliefs of the ancestors of the colonizers of the American continent.

The European Folklore: Kelpie e water-horses

The British Isles and Scotland in particular are the homeland of lake monsters in the collective imagination. In addition to the very famous Nessie there is Burach-Baohoi, a giant leech that would infect Loch Tummel in Perthshire, while Loch Lindie would be the lair of the shapeshifting monster Madge, capable of transforming itself from time to time into a crow, a cow, a horse or a hare. Lurking in the waterways would then be the monstrous reptile with poisonous saliva Lavellan and the bizarre Glaistic, a monstrous goat man. The list could go on and on. The most widespread (and feared) creatures were undoubtedly the kelpies, also known as water-horses. Let there be the word kelpies that's the word water horse they first appeared in written form towards the end of the eighteenth century but must have been in use since time immemorial among the Scottish population. The etymology of the word is not clear but it is thought to derive from the Gaelic lime, or "heifer".

In the Highlands a distinction is made between two types of water horse: I'Each-Uisge that infests lakes and seas and the aforementioned kelpies, which instead dwells in waterways. Like other Scottish monsters the kelpie is a shapeshifter. According to legends usually it takes the form of a horse and appears at night on the shores of lakes and rivers where it approaches unsuspecting travelers. The unfortunate get on the horse and realize too late the fatal mistake made: the kelpie begins to gallop at full speed towards the waters, diving into it before the rider has time to react, dragging him with him into the depths of the lake. The kelpie can take on several other forms such as that of a handsome young man or a beautiful girl, but one of his favorite forms appears to be that of a wild man covered with hair that attacks unfortunate travelers, suffocating them with powerful hands. Sometimes theEach-Uisge manifests itself as a giant water bird, the mythological boobrie.

These creatures they would make their lair near ancient monuments. Tradition has it that theEach-Uisge of Loch Pityoulish dwellings within a crannog, a submerged prehistoric settlement, while in Wales kelpies would roam the sites of ancient Roman encampments. Exploration of the bottom of Loch Ness revealed structures that could be megalithic sites by now submerged.

The presence of kelpies is often also linked to luminous phenomena, some of them in fact would disappear into thin air, others would have sparkling bodies. Despite their magical nature, it is believed that Kelpies can be killed using a silver bullet. Legends say that once the Ceffyl-dwr, Welsh cousin of the kelpie, dissolves into fog. The kelpie's body would lose all consistency and according to some stories the corpse of a Each-Uisge it would be a soft mass that resembles a jellyfish.

Researcher Roland Watson, who collected a huge number of books and publications mentioning kelpies before 1933, found that 43,6% of the reports concern Loch Ness. The lake was indeed traditionally considered inhabited by kelpies and related creatures, a belief that still had to be felt and rooted in the nineteenth century. The Scottish Academician John Francis Campbell tells how the inhabitants of the shores of Loch Ness believed that the loch was populated by creatures they called water bulls, and how it was believed that they were able to change shape at will.

That the tradition was still alive and felt confirms it an article published in the summer of 1852 onInverness Courier. The article reports how on a summer day the inhabitants of Lochend had spotted something swimming in the lake. It appeared to be two animals. People flocked to the banks to observe the unusual sight and discuss what the two animals were. Soon the inhabitants were convinced that it must be two monsters. So the inhabitants of Lochend armed themselves with hatchets and pitchforks and prepared to face the creatures. But once they got closer to the shore, the two monsters turned out to be just a pair of ponies refreshing themselves, so the Lochendans put their weapons away. This episode confirms that the belief in kelpies, or in any case in nefarious creatures inhabitants of the lakes, was rooted and felt still in the modern age.

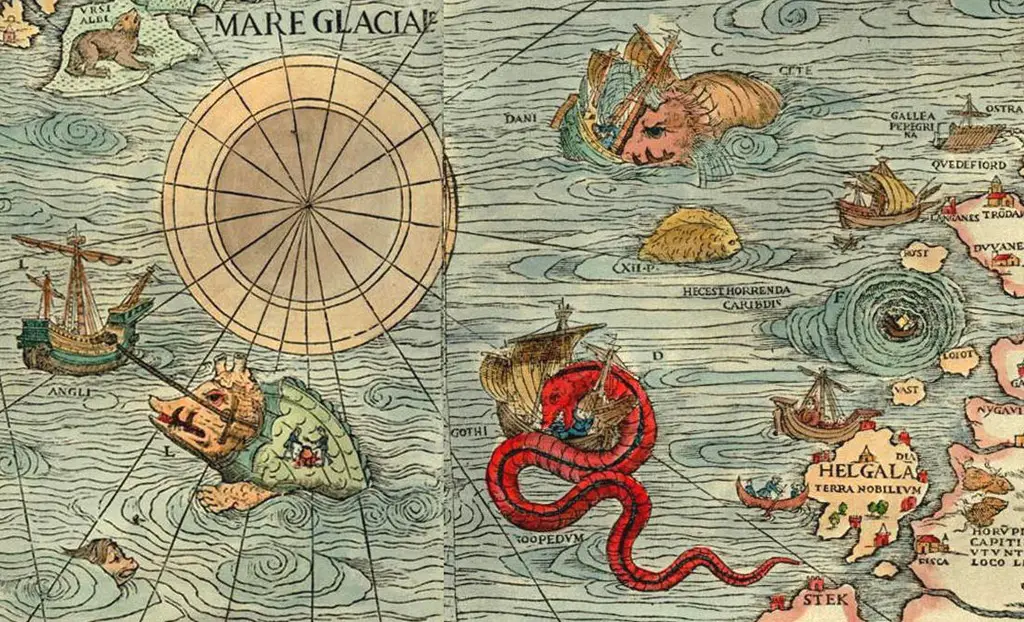

Of Figure water horse it is found in various parts of Europe including Scandinavia, Russia, France and Italy. The water-horses were known in particular in Scandinavia where they were distinguished from sea snakes, so much so that Olaus Magnus tells us about epic battles that took place between the two types of beasts in the Norwegian fjords. Also Olaus Magnus reports that the water-horse has "hooves like a cow is and at home both on land and in water». Another creature of Scandinavian folklore that may have influenced modern tales of lake monsters is the Lindorm, often described as a snake-like monster with a mane.

According to Meurger, the belief in kelpies and other similar creatures formed the basis for modern lake monster stories. Kelpie legends still retain various magical elements, such as the ability to change shape and subjugate the will of humans, which makes them more akin to fairies and to the small people than to the modern monsters that cryptozoologists hunt. This mythological material will arrive in North America where it will contaminate itself with an already existing milieu of beliefs about monsters or that of the Native Americans.

Gods and Monsters: Myths of Native Americans

As we have already seen, during his research Meurger came across native beliefs about lake monsters. The focus on the subject is so rich and varied that Meurger himself defines it «the Eldorado of water monsters». This body of belief is not only exceptional for its variety and quantity, but also for the much more complex role that these mythological figures had within the cultures of the American continent.

Native Americans, like Europeans, believed in aquatic monsters modeled on land animals. The Cree of Oklahoma believed in the existence of gods water people, beings similar to undines and sirens, and ai water-calf and water bison, but there were also feared beings like the water-tiger. The Wintuns of Northern California believed that a monstrous being called water panther appeared on the occasion of the floods. Also Mishipizhiw, the demigod revered by the Ojibwa tribe of the Great Lakes, was represented as a monstrous aquatic feline. Similarly the Peoria tribe of Illinois counted in his pantheon Lenapizka, a monster with feline features capable of living both on land and in water.

Other entities much feared, especially by the tribes settled along the lakes, they were i water grizzlies, who believed themselves responsible for the eddies in the waters and the disappearance of canoes and fishermen. However, there is no shortage of indefinable creatures, without a counterpart on the mainland. This is the case with the Mi-Ni-Wa-Tu, that the natives believed infested the Missouri River: it is described as a bright object that moves at full speed, causing very high waves. It would be a creature covered in red fur, with only one eye and a long horn, with the body partly of bison and a huge serrated tail.

However, no belief is as widespread as that in Great Serpent of the Waters, a figure that is found in the mythologies of peoples throughout the North American continent, a great creature considered the ruler of the waters. The name and its nature vary from population to population. The Haidas of British Columbia, they know him as Sisiutl, the two-headed snake. For other groups such as the Abenakis it is a "horned snail". For the Pentagouets it is a deer horned worm, while for the Kiowas it is instead a «horned crocodile». Other populations such as the Chickasaw, Peublos and Zuni speak only of a generic "Horned snake". These creatures are said to dwell as much in the sea as in caves near lakes.

From the mythology of the natives we learn that these creatures suffer over time various metamorphoses and can themselves transform the unfortunate animals that fall into the water into monsters. This is the case of the bear who fell into the well where he lived Amhuluk, in the mountains of Oregon, which was transformed into the monstrous Atunkai.

According to the legends of the Pentagouets the monster Weewilmekq it was once a small worm no longer than ten centimeters. Throwing himself into the water, he grew to be the size of a horse. Sometimes this creature is credited with an ability to change shape not too dissimilar to that of Scottish kelpies. The Shawnees believe that the "great reptile" Msi-Kinepikwa sometimes appears as a fawn, while the Kwakiutl tell of how the monster Sisiutl can take the form of a very common salmon. These horned snakes can also take human form and then capture the women with their tail and drag them into the depths of the waters.

The Monster and the Shaman

The relationship that the natives had with these creatures, which they called "the mysteries of the waters", very articulated and complex, is well exemplified by a myth that tells of the clash between the horned snake that lived in Lake Ontario and the Iroquois hero Gun-No-Da-Ya: after a long and exhausted fight that does not had seen neither of them prevail, the snake decided to try to befriend the hero by saying:

“I'm your friend and I'll teach you how to harpoon fish at night. I will reveal the secrets of the waters to you. Come with me. I will lead you to my abode among the rocks, on the seabed, where the sun never shines. Come and hold on to my long mane, it's full of fish that got caught in it. "

Gun-No-Da-Ya was not fooled and bent his bow. At that moment the beast with a lightning movement swallowed him. Only the power of Thunder, the snake's natural enemy, will then allow a Gun-No-Da-Yadi escape the beast. In this story the horned snake is identified as a threat, a personification of the brute force of nature. But at the same time he is the keeper of those secrets that can allow man to dominate the elements.

Certain men could negotiate with these beings to obtain benefits for the whole community, but this was only granted to initiates. The mere sight of the creature by one who was not adequately prepared could have dire consequences. Who had the bad luck or the imprudence to see the monster Mi-Ni-Wa-Tu he went mad and died in excruciating pain. Sisiutl's vision caused the bones to deform. There are tales of unfortunate people who reported wounds on their skin attributable to the distinctive physical characteristics of the monster, a sort of stigmata: a child who managed to escape the monster Amuluk found scars of the shape of the monster's horns on his body.

The horned serpent occupied an important place in the culture of many peoples of North America, and this is testified by the fact that numerous representations of it have survived. For example in the Zuni culture of New Mexico, the horned snake, here called Kolowisi, it is represented as a horned reptile with numerous fins. In the sculptures produced by the Inuit of Alaska the monster is represented as a snake with short horns, a long neck and a long tail.

The most interesting representations are certainly i petroglyphs discovered in the Great Lakes region. These representations were made in places that were thought to be inhabited by monsters. The natives were convinced that the creatures represented in them lived inside the rocks, which were thought to conceal a hollow wall. In British Columbia these paintings were thought to be the work of spirits, particularly those located in rocks above the waters. The paintings disappeared when the spirit left that place. The natives were careful not to look at the paintings that were found in the rocks on Lake Nicola, home of the monster Heitilik, if they didn't want their canoes to be overturned by sudden strong winds.

The effigies of the Great Lynx or the Horned Serpent were the object of tobacco offerings and other sacrifices for the purpose of preventing storms. In certain cases the waters submerged these petroglyphs for part of the year, in winter, and then reappeared in spring, thus creating a link between these beings and the cycles of the seasons. The most famous depiction of the Great Horned Serpent is the petroglyph discovered near Lake Superior from Henry Schoolcraft around 1850. It depicts some canoes and three monstrous figures, one with legs and horns, and the other two similar to large snakes. The scene represents the crossing of Lake Superior by the warrior and shaman Myeengun. The creatures would be his protective spirits, namely Mishipizhiw, the Great Lynx, the god of water of the Ojibwa people and the great Horned Serpent. Without the help of these entities, the enterprise would have been impossible.

Similar petroglyphs have been found to be found along the Pacific coast, and it has been speculated that they were sites where young natives experienced the visions that marked their entry into adulthood. The monster in this case would symbolize the guardian spirit. In the Great Lakes region the horned snake symbolizes those aquatic entities visible only to the elect, who accompany them on their travels, calming the waters, the same waters that can overwhelm the uninitiated.

On the eve of important travels they paid each other sacrifices to lake monsters to keep the waters calm. The trapper Nicolas Perrot collected many stories about it from the Outaouais tribe:

« They worshiped the Great Tiger as a god of the waters, who is called by the Algonquians and others, who speak the same language, Mishiphiziw. They think that Mishiphiziw lives very deep, and that it has a long tail which causes strong winds when it moves to drink; but if he shakes it vigorously it causes great storms. In the journeys they have made, they invoke him in this way: "You, who are the lord of the winds, bless our journey and grant us peaceful time". This is said by smoking tobacco from a pipe and blowing the smoke into the air. But before embarking on even longer journeys they make sure to break off some dog's head, which they then hang from a tree. "

The custom of sacrifice survived until the nineteenth century and was also borrowed by the first white pioneers, who threw traps and guns into the water as an offering.

In an account dating back to the eighteenth century, Account of Captivity, drafted from English Alexander Henry, in which he recalls the period he spent as a prisoner with a tribe of the Great Lakes, he tells of similar practices. In an episode told by Henry, the Indians, who were about to leave for a trip by canoe, are panicked and terrified when they discover a rattlesnake, a sign of bad omen:

" Once sIn the boat, the weather quickly deteriorated and the Indians became frightened, frantically begging the rattlesnake for help. The waves became progressively higher. At eleven in the morning a storm began and we expected to be swept away at any moment. After the prayers, the Indians resorted to sacrificial offerings to the rattlesnake god, the Manito Kibic. One of the leaders took a dog, and having tied its front legs, threw it overboard, begging the snake to protect us from drowning. and asking to appease his appetite with the dog carcass. The snake did not soften the winds. After that another leader sacrificed a second dog. "

It should be noted that among the Iroquois the great Horned Serpent was often depicted as a rattlesnake. Mediating between the tribes and these creatures were the shamans. Among various tribes, the shamans derived their powers from the great snakes of the lakes, as at the Lenapes, where the shamans were gathered in the brotherhood Kitzinackas ("The great snakes") or as the Omaha shamans, who said they personally met the monstrous wakandagi and how they, instead of devouring them, had granted him magical powers.

It follows that among certain tribes aquatic monsters played a central role in initiations. The descent into the monster-infested waters is the supreme test in different cultures, the test that allows you to get in touch with spirits. In many cases, such as that of the Inuit, immersion into the depths occurs in the form of a vision in a trance state, in which the shaman must face a kind of descent into hell, avoiding the many pitfalls along the way, to reach the goddess of marine animals.

In other cultures, immersion is real and is the focus of initiations. In the California Klamath culture, the would-be shaman goes alone and at night to bathe in so-called "spirit places" upon the arrival of puberty. There the initiate was grabbed by monsters and dragged to the bottom. At that point he lost consciousness and then woke up on the shore, bleeding from the nose and mouth. During the time when the initiate was unconscious, he was instructed by supernatural beings through dreams. A similar tradition is found among the Yukon, where families instructed young people on what were the points to dive at night, where "a creature would drag them to the bottom of the waters where he would speak to them»Revealing to him how to gain strength and knowledge. One known site for this type of initiation is Crater Lake in Oregon, which was believed to be inhabited by called sea snakes To Kas.

Shamans who received their power from water monsters were also able to take their form. According to a legend the shaman Medshelmet of the Passamaquoddys faced a rival shaman of the Micmac tribe in a magical duel. The scene of the clash was Lake Boyde in Maine. Medshelemet turned into Weewilmekq, the horned worm, while his opponent took the form of Kitchi-at'husis, the great snake. The clash was so violent that the waters are still rough today. Eventually Medshelemet got the better of it and defeated the opponent.

Modern Monsters

As we have been able to illustrate in the course of the article, the belief in monstrous creatures that inhabit lakes is not only ancient but also widespread among very distant cultures. Modern lake monster stories have taken root in a pre-existing substrate of beliefs and myths. Cryptozoologists have often challenged these beliefs as evidence of the existence of monsters in flesh and blood. Meurger in his study strongly rejects this interpretation, asserting that one cannot look at these beliefs, the fruit of a pre-modern sensitivity and vision of the world, as factual evidence in the contemporary sense of the term.

Despite the numerous similarities between modern tales of monsters and the most ancient beliefs (starting with the equine characteristics of monsters), it is inevitable to ascertain that There are notable differences between creatures such as Scottish kelpies, Amerindian horned snakes, and modern lake monsters. The former, more than creatures in flesh and blood, are akin to spirits and are endowed with magical attributes such as that of changing shape. In the case of horned snakes, their characterization as the personification of the elements brings them closer to real deities.

What caused these beliefs to evolve and transform? According to Michel Meurger it was a process he calls «scientification of folklore " (scientification of folklore). This term, borrowed from the study The Meaning of the Loch Ness Monster di Roger Grimshaw e Paul Lester, indicates the rereading of popular beliefs in the light of the Enlightenment mentality and scientific knowledge. An attitude that was very successful during the nineteenth century and that instead of eradicating irrational beliefs, he ended up giving them a new guise, more suited to the times and to the new rationalist mentality that was gaining ground. In many cases there was an attempt to find a fund of truth in folk tales or superstitious beliefs, reading them as "facts", stripping them of the supernatural element and trying to explain the rest with the latest scientific discoveries.

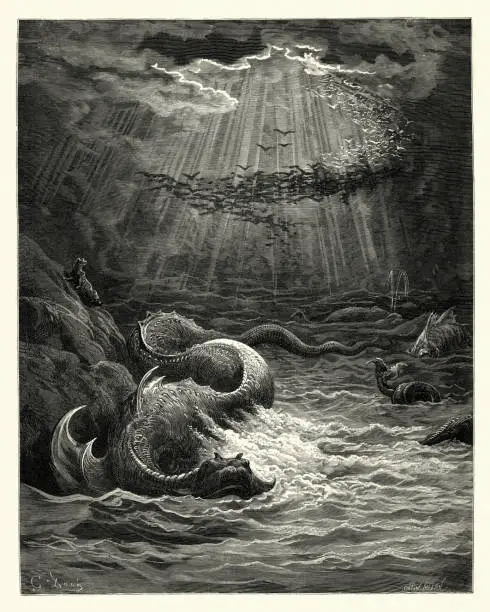

In the case of lake monsters (and by extension of sea monsters) a great impetus in this sense was given by the paleontological discoveries that during the nineteenth century changed the perception of the history of life on Earth. The bones of prehistoric creatures that emerged from the earth deeply affected the popular imagination and appeared as a confirmation of the old stories of dragons and monsters. As he wrote Victor Hugo in 1864, "the bones of those dreams are now in our museums».

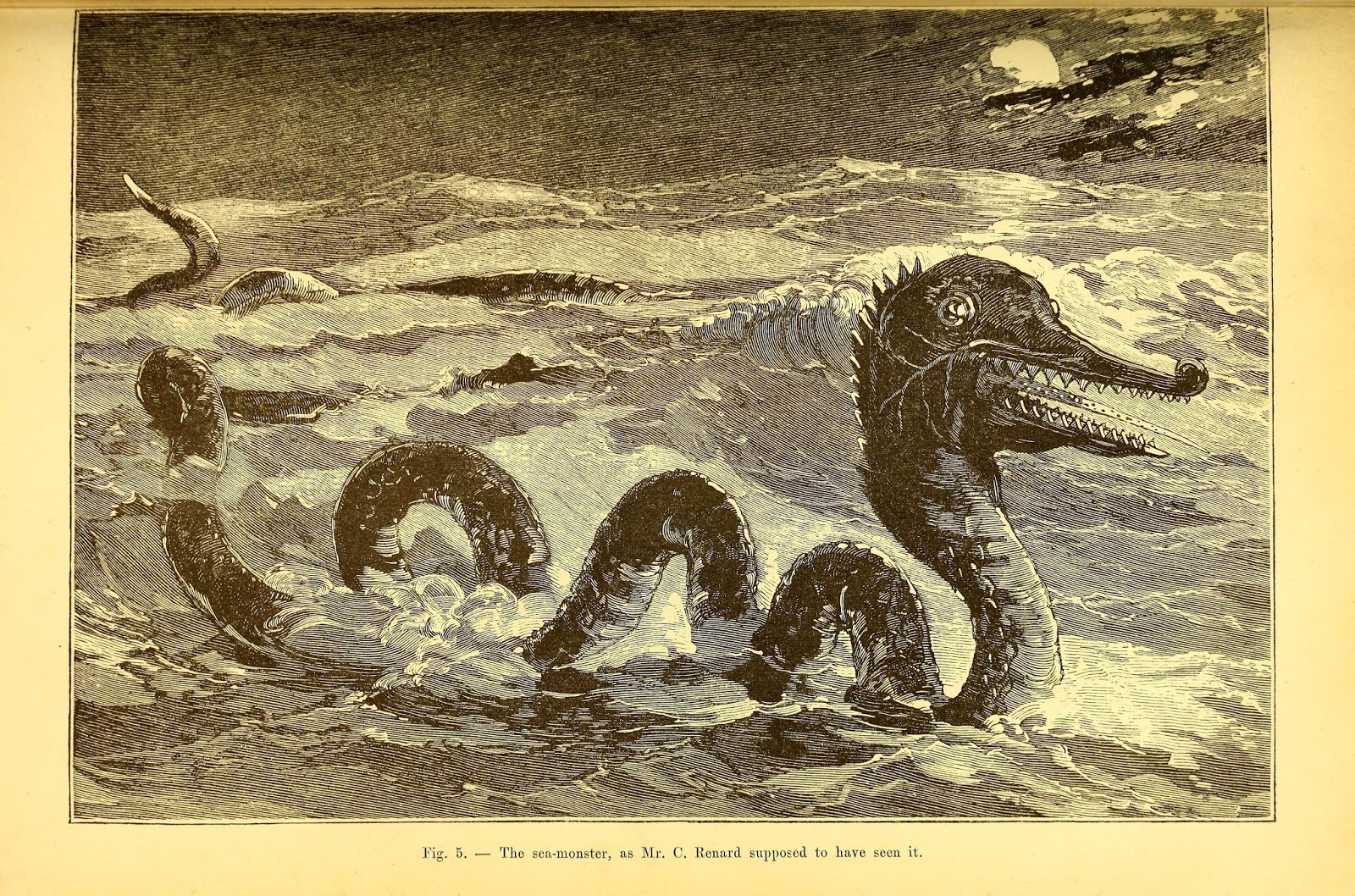

In the public eye if these creatures had existed in the past it was perfectly plausible that somewhere there were some survivors. By going from being magical creatures to being living fossils, monsters could continue to live in the age of reason. Since the explosion of sightings in 1933, the privileged hypothesis about the identity of the Loch Ness monster has been that of the prehistoric marine reptile, specifically the Plesiosaur, an aquatic reptile coeval of the dinosaurs, with a long neck, now become one with Nessie in popular culture. The primitive whale called Zeuglodon was called into question for the American monster Champ, while Ponik would be an unknown breed of marine iguana.

Lake monsters are not the only fantastic beings to have undergone this process: it is not difficult to see the same process at work in the myths about Sasquatch and Yeti, modern descendants of the sylvan men of the Middle Ages, or create as many of the elements of tales about the small people have been incorporated into UFO mythology. The so-called "alternative realities" seem to take the place of that mythical dimension of which the disenchantment of the world has deprived modern man.

The persistence of these myths suggests that in a sense we need monsters in our world: they are the projection of all that is stirred beneath the surface of consciousness and it is no coincidence that their abodes are the depths of the waters or the earth. But monsters are also the very embodiment of wonder. Perhaps as long as man exists there will be monsters somewhere.

REFERENCES

Michel Meurger and Claude Gagnon: Lake Monsters Traditions: A Cross-Cultural Analysis

Nick Redfern: Nessie! Exploring the Supernatural Origins of the Loch Ness Monster

Maurice Moscow: Monsters of the Lakes

5 comments on “From the Kelpie to the "Horned Serpent": lake monsters in Scottish and Amerindian folklore"