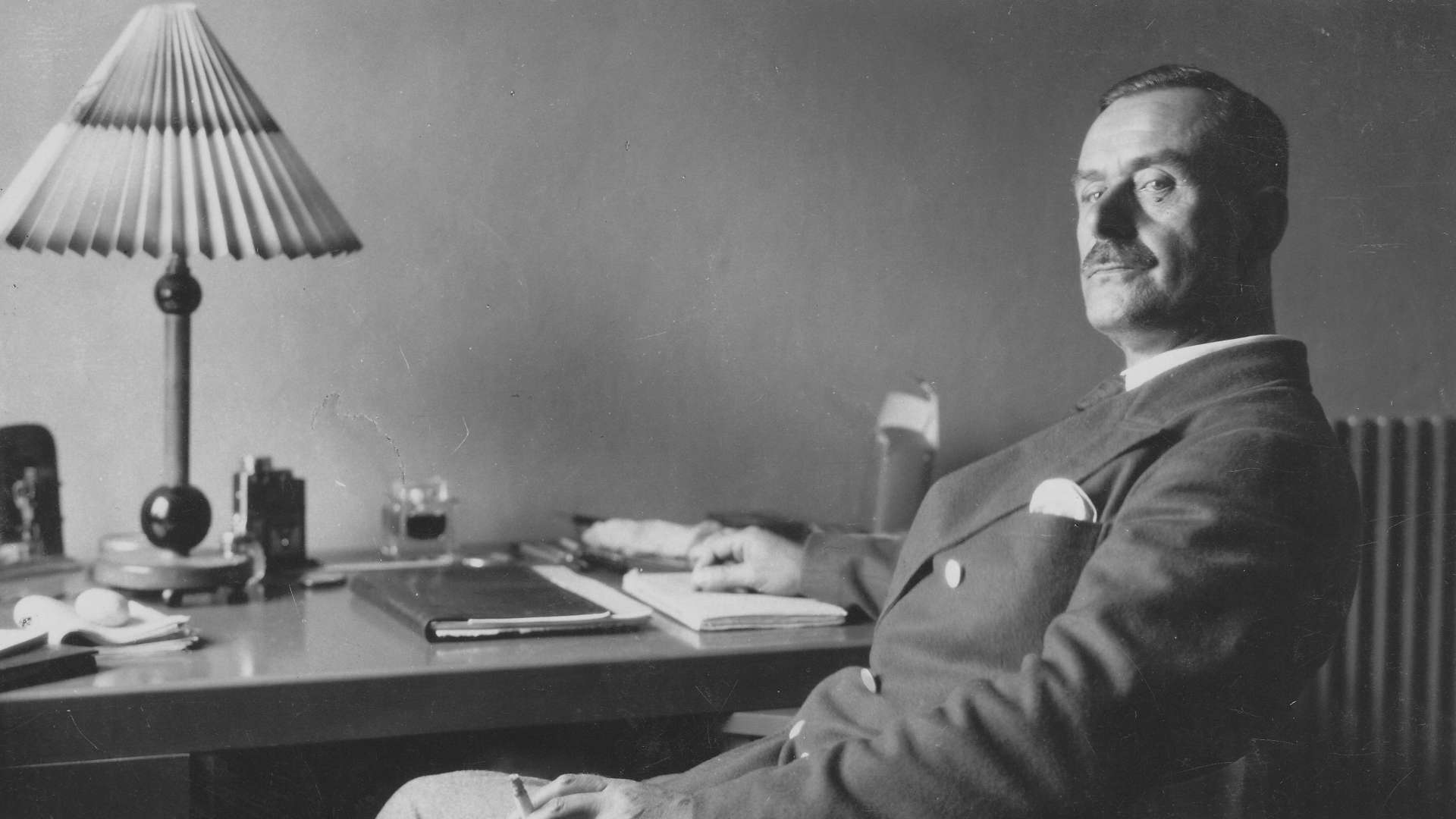

65 years ago, on August 12, 1955, Thomas Mann, one of the most influential storytellers and thinkers of the first half of the twentieth century, left this world. Here we see how - taking a cue from Freud, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer - Mann considered the journey to the mythical and archetypal abysses of man as a return to the past, but with the prospect of delivering it, purified of irrational error, to the future.

di David Simonato

taken from the thesis "The image of man in the works of Walter F. Otto, Károly Kerényi and Mircea Eliade", 2014-15

The interest in the myth has always been a constant in the aesthetic field, because only with the myth did one have the palpable impression of approaching the vital totality of man, placed in a past in which the roots of the same historical condition seemed to be rooted. . As indeed the contents of the myth were the essential reserve of meaning from which to draw to create artistic works who freed them from the specific religious bond, handing them over to the enigmatic truth of forms, likewise placed before the gaze a nucleus of unresolved meanings.

This peculiar and evocative ambivalence, constantly oscillating between clarity and obscurity, civilization and barbarism, reaction and progress, in turn summarizes the double possibility of judging them. The appeal to a comparison with these concepts, which is addressed to us by the literatures of the past as well as modern ones, in fact tests thought in its very instances, discovering a central and current point of our time, still divided between a climate of suspicion, given by a convinced Enlightenment overcoming of an now adult rationality, and a romantic nostalgia for an irrational side, nourished by reactionary anti-modernism [1].

In the twentieth century, the myth returned to debate precisely in the face of this alternative, in an attempt to explain the resumption of mythical-religious concepts that from literature and philosophy have extended to involve social life; think in particular of the well-known irrationalistic currents which, praising the regression to the myth and the archaic, have ideologically exploited the myth in the direction of political consensus [2]. This rediscovery of the mythical dimension seemed to go hand in hand with the denunciation of a rationality abandoned to itself which, drawing myth from its depths, sought to make up for the loss of its legitimacy. On the other hand, in the age of disenchantment it will no longer be possible to aim at establishing contact with transcendence and will have to be satisfied with the possibility of experiencing myth as the will to life and the will to power. [3].

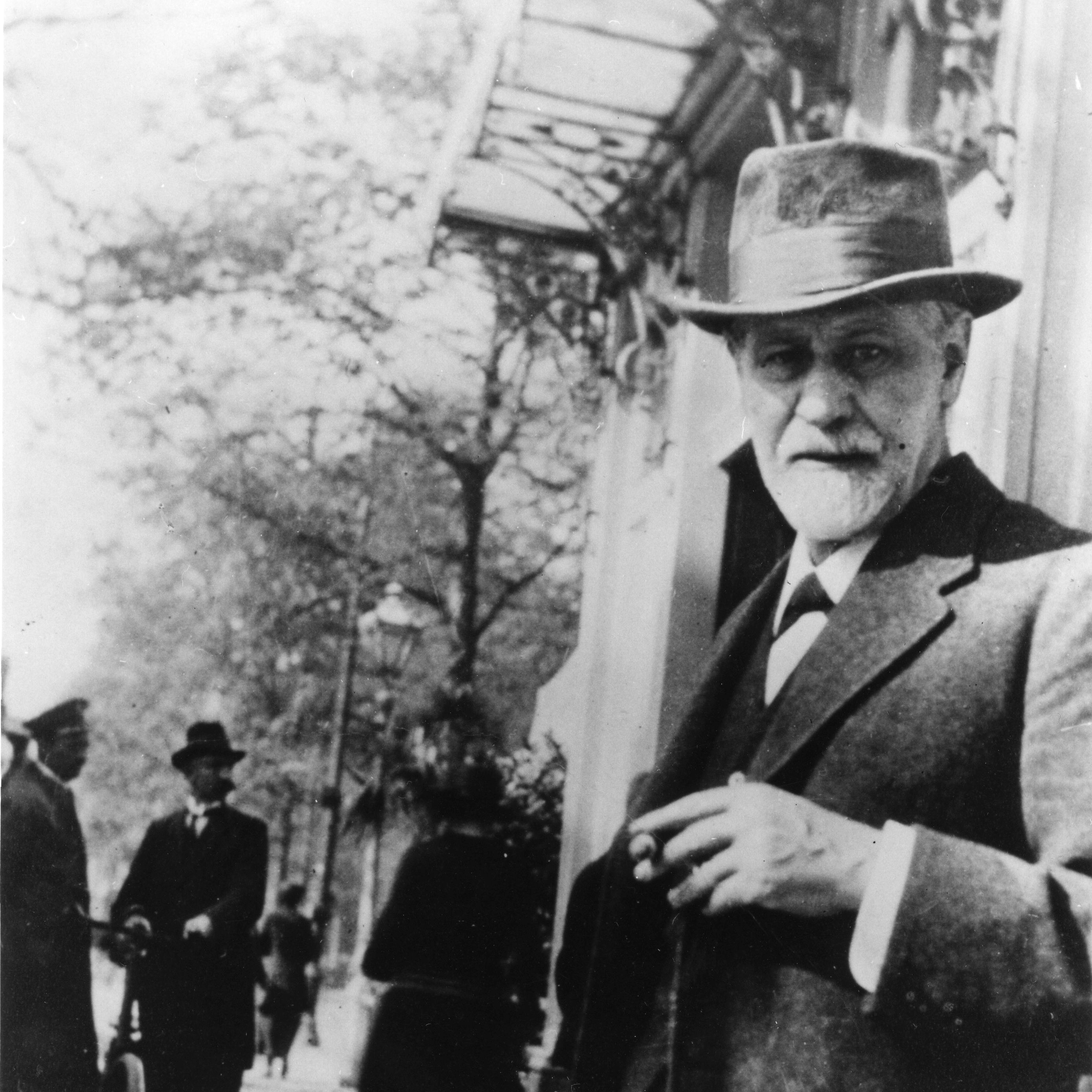

This decadent use of myth, which had to do with that exhaustion of reason that Freud analyzed ne The discomfort of civilization [4], found between the 20s and 30s in Thomas Mann (1875-1955) an authoritative voice ready to denounce its inherent danger. In fact, contrary to many trends of the time, he understood how a certain distorted reading of romanticism contained the easy risk of an anti-humanistic use of myth, enhancing its chthonic side, of blood and soil, of past and death. [5]. Placing himself as a staunch defender of a humanism in which the study of myth and religion, relying first of all on the strength of a moral reason, placed man at the center of the investigation, Mann sought a way to overcome the risks of this return to past, also aware of the need to maintain the nocturnal side of reason, the creative source of the spirit.

The first novel of the great mythological tetralogy Joseph and his brothers (Joseph und seine brothers), highlighting the particular link between the work and trends of the time, reveals a significant search for a new access to the myth. Emblematic in this sense is the famous Prologue:

Deep is the well of the past. Or shouldn't we say it inscrutable? Inscrutable also, and perhaps then more than ever, when we discuss and question the past of man, and of him alone: of this enigmatic being that contains within itself our existence by nature oriented towards pleasure but beyond a miserable and painful nature. , and whose mystery, as it is understandable, forms the alpha and omega of all our speeches and all our questions, gives fire and tension to our every word, urgency to our every problem. Because precisely in this case it happens that the more one digs into the underground world of the past, the more deeply one penetrates and seeks, the more the beginnings of the human, of its history, of its civilization reveal themselves to be completely unfathomable and, while making the sounding go down to fabulous temporal distances, gradually and more and more recede towards bottomless abysses [6].

For Mann, the journey to the mythical depths of man is indeed a return to the past, but with the prospect of delivering it, purified from irrational error, to the future. In fact, the years of writing the novel belong to the period in which Mann begins to question himself theoretically about the problem of myth, trying to demonstrate how in history some returns to the past have actually proved to be the necessary prerequisites for a development. [6].

Fully believing in overcoming the cult of romantic sentiment announced in theAurora by Nietzsche, Thomas Mann takes the lesson of "reaction as progress" [7], finding in Freud the highest contemporary example he has succeeded in stripping romanticism from its mystical guise to make it science, to show how the interest in vital momentum and emotionality do not necessarily degenerate into the exaltation of the object at the expense of the intellectual sphere, but rather that they proceed in the direction of greater awareness [8]. What would then make it possible to make the mythical or metaphysical aspect rationally justifiable is psychology, thanks to which the myth penetrates the conscience, granting reality the possibility of being experienced as an eternal present [9]. In fact we find written in another passage of the novel that:

The experience did not consist so much in seeing something that belonged to the past repeated itself, as in the fact that that past became alive and present. But it could become present because the circumstances that gave rise to it were present at all times. […] Everytime: this is the word of the mystery. The mystery knows no time, but the form of what has no time is the Here and Now [10].

A few years later, in the 1936 conference Freud and the future [11], Thomas Mann returns to deal systematically with the father of psychoanalysis, seeking an aid in the study of his thought a theorization of the myth in view of a reconciliation between the unconscious and reason. Curiously recognizing a Schopenhauer, "Melancholy orchestrator of a philosophy of instinct" [12], the role of forerunner of depth psychology, having taught the primacy of instinct over reason and recognized the will as the foundation and substance of the world and of man [13], Mann unites the two thinkers in the same emancipatory role from the illusion of a world view of phenomena as purely accidental realities. The reversal of perspective in view of a new anthropology lies in tracing everything - and therefore also the irrational and the mythical - to a work of the soul, unmasking and recognizing every to happen as a do [14].

In Giuseppe in fact the humanization of the myth is the descent of the god into the human, so that his story on earth becomes the initiatory itinerary of man towards himself, therefore the history of the human soul. Humanization of the myth meant on the one hand the pedagogical use of the myth, as a founding tool for the novel of the soul, but also the controversial renunciation of myth as an extrahuman value [15]. Mann, the reader of Freud, recognizes in the dynamics of the unconscious the primitive and irrational side called Es, la will Schopenhauerian, while he sees the ego, the part in relation to the external world that draws advice from experience, as intellect [16].

Concluding that the giver of reality is in man himself, as well as arguing that the human need is at the same time joined to the divine one, inevitably leads to a new look at the role of myth and its specific function of exemplarity. Myth is a fiction, in a strong sense, in the active meaning of shaping: it is therefore a construction of fictitious archetypal realities, whose role consists in proposing, if not in imposing, models and types, in whose imitation an individual can grasp whether himself and identify himself. Consequently, the consideration that the problem of myth cannot be separated from that of art, not only because the myth would be a sort of collective creation, but above all because the myth, which the work of art exhibits, is the mimetic tool par excellence [17]. Thomas Mann is aware of the fundamental identifying role of the myth, in psychoanalysis as in any kind of poetic activity, for which the return has the value of an imitative approach to life:

In the expression "depth psychology" the word "profound" also has a temporal meaning: the primordial foundations of the human soul are also primeval age, that deep well of the times in which myth is at home and constitutes the first rules and forms of life. Myth is in fact the foundation of life; is the timeless scheme, the religious formula in which life, after having drawn from the unconscious the traits of the myth and reproducing them, converges [18].

The myth, returning to light and becoming present, then reveals to man the certainty that there is a real possibility of knowledge and control of one's nature:

But what if the mythical aspect became subjective, if, passing into the acting Ego, it awoke, so that the latter would become, with a happy or gloomy sense of pride, aware of his own "return", of his own typical character? […] Only in this case could we speak of "Lived myth" [19].

This consciousness belonged to the ancients. Indeed:

Their ego was, so to speak, open to the past, and from there it drew, to repeat them in the present, many forms, which thus, through it, returned to new life. The Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset expresses this concept by saying that the ancient man, before doing something, took a step backwards, like the bullfighter who takes the momentum for the fatal blow. In the past he was looking for an example in which to immerse himself like a diver in his diving suit and then, thus deformed and at the same time protected, immerse himself in the problem of the present. [20].

Modern man on the other hand, Thomas Mann suggests, in order to safeguard the essential value of myth, it is necessary to refer to the lesson of three great "masters of morality", Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Freud who, daring to go beyond conventional certainties, have tried to reconcile the light of modern rationalism with the night of the soul and myth, revealing at the bottom of human nature the dark spheres of the will, the Dionysian and the unconscious, thus inaugurating a new kind of humanism.

Note:

[1] At the crossroads between these perspectives are the German authors of the so-called Mythos-Debate, such as Manfred Frank, Odo Marquard and Hans Blumenberg, who, starting from the theses of Max Horkeimer and Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of the Enlightenment, Turin, Einaudi, 1997 [ed. or. Dialectic of Enlightenment, 1947] in relation to the mythical error that connotes modern instrumental rationality itself, or in relation to the so-called mythology of reason consequent to the democratization of knowledge, put forward the hypothesis of a thought that is both mythical and rational. A discussion on these issues can be found in the monographic issue of "Aut aut", 243-244, 1991, titled "The myth in question".

[2] Some interesting hypotheses on the philosophical and aesthetic aspects of the National Socialist myth can be read in the short essay by Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe - Jean-Luc Nancy, The Nazi myth, edited by Carlo Angelino, Genoa, Il melangolo, 1992.

[3] Paraphrasing some places in Manfred Frank, op.cit.

[4] See Sigmund Freud, The discomfort of civilization and other essays, Turin, Bollati Boringhieri, 1971. This edition includes, in addition to the aforementioned essay of 1929, also the classic text on the psychology of religion of 1927 The future of an illusion.

[5] See Margherita Cottone, Thomas Mann: myth, psychology, humanismin Mythologies of reason. Literatures and myths from Romanticism to Modern, edited by Michele Cometa, Pordenone, Studio Tesi, 1989, pp. 269-313. I refer to this accurate and important contribution for the in-depth study of the themes that I will have to leave out here for obvious reasons.

[6] Thomas Mann, The stories of Jacob [and. or. Die Geschichten Jaakobs, 1933], in Ditto, Joseph and his brothers, edited and with an introductory essay by Fabrizio Cambi, translation by Bruno Arzeni, volume I, Milan, Mondadori, 2006, p. 5.

[7] See for example Thomas Mann, Freud's position in the history of the modern spirit [and. or. Die Stellung Freuds in der modernen Geistgeschichte, 1929] in Ditto, Nobility of the Spirit and other wise men, edited by Andrea Landolfi with an essay by Claudio Magris, Milan, Mondadori, 1997, pp. 1349-1375.

[8] See. Ivi, pp. 1349-1353.

[9] See. Ivi, pp. 1370 ff.

[10] See Margherita Cottone, op.cit., pp. 283-284.

[11] Thomas Mann, The stories, cit., p. 30.

[12] Same, Freud and the future [and. or. Freud und die Zukunft, 1936], in Ditto, Nobility of the Spirit, cit. pp. 1378-1404.

[13] Ivi, P. 1380.

[14] See. Ivi, P. 1384.

[15] See. Ivi, P. 1389.

[16] See specifically pages 263-267 of Furio Jesi, Thomas Mann, "Joseph and his brothers"in Mythological materials. Myth and anthropology in Central European culture, Turin, Einaudi, 1979, pp. 253-271.

[17] See Thomas Mann, Freud, quote., pp. 1385-1389.

[18] See Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe - Jean-Luc Nancy, on. cit., pp. 34-36.

[19] Thomas Mann, Freud, cit., pp. 1394-1395.

[20] Ivi, pp. 1395-1396.

[21] Ivi, P. 1397.

A comment on "Thomas Mann, the nocturnal side of reason and the depth of the Myth"