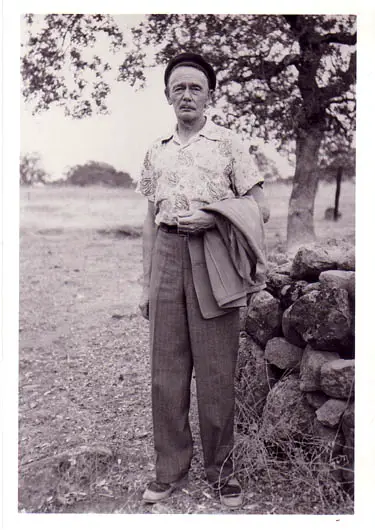

Aristocratic temperament, decadent prose, oneiric visions: we retrace “Poseidonis”, one of the most significant narrative cycles of Clark Ashton Smith.

di Lorenzo Pennacchi

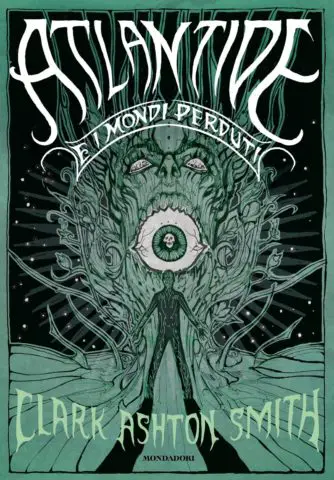

A few years after the collection was released Atlantis and the lost worlds, also in Italian Clark ashton smith it is no longer relegated to a very narrow niche of readers. However, as much as his circle is growing, the American author, with his own sword and sorcery, his (one) oneiric verses and his decadent prose, will presumably never be a fantasy writer for many, as Tolkien or Martin to be clear. After all, already in 1923 HP Lovecraft he had clear ideas about the reasons for the commercial failure of his friend and correspondent:

« More sincerely sensitive to the wildest dreams of men, and more sublimely cosmic, in his imaginative vein ofa fantastic chaos not marked on the maps, than any other verser from the time of Poe, Mr. Smith is relatively little known outside the Californian milieu due to the tastes of an audience wary of beauty and the adventures of the spirit.." [1]

Similarly, in 25 Alfred Galpin, Lovecraft's correspondent and future professor of romance literature, after having praised the first Smithian poetic collections, expressed himself thus:

« Why then remains unknown? In the first place, because he is a close contemporary of the intellectualistic taste for modernism, to which his work owes very little. Furthermore, there are very few admirers of the grotesque and the average man of culture, finding much of the book less than the best possibilities of the author, passes on and thus loses the gold that is mixed with the sand. » [2]

In the volume, published by Oscar Mondatori and edited by Joseph Lippi, there are four Smithian narrative cycles. The big one is excluded Hyperborea, but the (not only) medieval scenarios of Averoigne, the futuristic suggestions of zothique, the sidereal spaces of xiccarph and reminiscences of ours Atlantis they are able to drag the reader into other dimensions, not only from a space-time point of view. As Lippi observes in his introduction:

"The other dimensions Smithian are not mere dislocations at other moments in history, but have a different qualitative value. More than on a wheel like that of time, it seems to be transferred on another plane of reality or unreality, that of astral travel and unbridled creativity. »

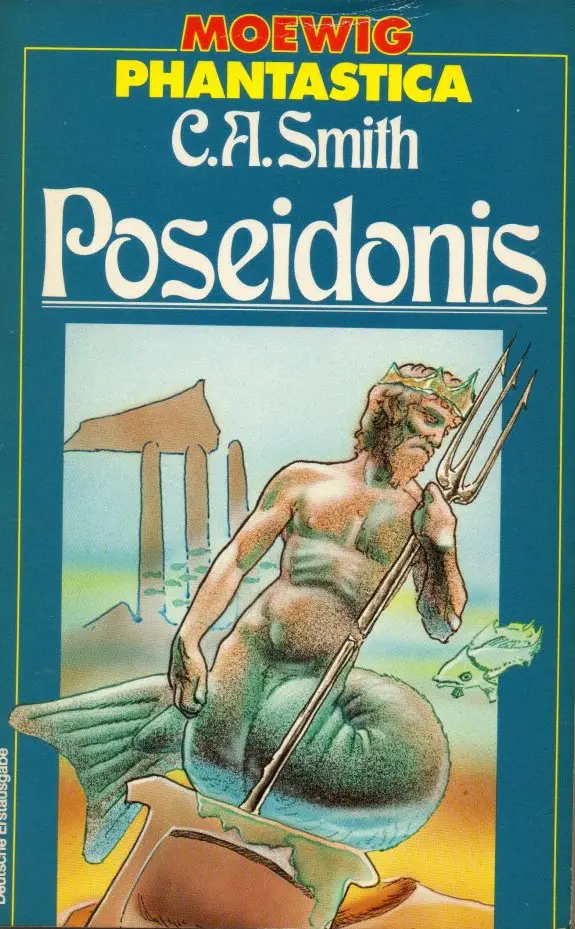

THEAtlantis which Smith gave life to in the thirties, through a letter, five short stories and two poems [3], deviates from the classic Atlantean imaginary. The burgeoning empire collapsed and much of the land was engulfed by the sea while Poseidonis, the last remaining island, is also doomed to collapse, despite attempts by magic and science to halt the apocalyptic process. As a fervent reader and translator of Baudelaire, Clark Ashton thus resumes a topos mythological which, since Plato, is present in Western history, shaping it with its refined aristocratic and decadent taste. The second and last verse of the poem Atlantis is emblematic in this sense:

« From the dome of the phosphorescent, starry ocean,

A ghostly light casts itself vaguely

On the altars of a garlanded goddess

With the flowers of a colorless, alienated plant;

Winged swims, in the skies under the foam,

As a silent starling the offspring of the rainbow sea. » [4]

Smith acknowledged that he consciously tried to deceive his audience through one sort of verbal black magic [5], a spell cast via the decadent prose and archaic language. A fantastic literature that, just like magical art, "imposes the revival of the past and the anticipation of the future, to the point of crossing over into the form of the unreal that most concerns us, that of legend and myth" [6].

Will you come with me to Atlantis? - asks the reader in the short opening poem, before leading him towards unknown islands, where to eat fruits never seen before and drink clear fairy wines distilled under the eternal moonlight. The initiatory spell also includes multiple gifts, including one crown of precious corals similar to blood flowers, a peacock blue dress with gold, copper and vermilion damask and another one black shamite with orange runes, woven by magic, without using your hands [7]. A few lines that allow readers to delve intosmithian dream universe, to feel part of the spell in which they are actively involved. After all:

« Smith's time travel is at the same time a journey into the dimensions of legend, but made literally and with the body. He is always a poet, not just a narrator, and it is proper to every poetic creation to be concrete as well as visionary […] The language of a magician, not of Tom Thumb. » [8]

The first and last story of Atlantis they have the fearful as their protagonist Necromancer Malygris, who lives in his megalithic tower in Susran, the capital of Poseidonis, spreading darkness over the minds of men. Neither The last spell the sorcerer tries to bring Nylissa back to life, his one-time love sacrificed on the altar of forbidden knowledge. Despite the immense power of her, he manages to evoke only the shadow of the girl, who, after a brief unreal apparition, dissipates in the air like smoke.

He writes about it Francis La Manno in his essay: «Time that has elapsed cannot return, not even by drawing on immense magical powers. Consequently, the arrogant man who falls intohybris and you want to put in open conflict with the Fact can only succumb miserably " [9]. Malygris therefore presents himself as an anti-hero with decadent features, so greedy in his power that he does not recognize the impossibility of going beyond the limits imposed by destiny. Of the limits that he seems to be able to cross in the second story, when, considered dead by the whole kingdom and before finally rotting, he inflicts a terrible curse on the eight sorcerers and the king who had coveted against him. The penalty is hellish:

« In the horrendous suffering of living rot they struggled on the floor and barely crawled over the cold mosaic. They moved like this, slowly and more and more imperceptibly, until the brain turned into a putrid, gray mass, the tendons detached from the bones and the spinal cord dried up. Within an hour, the curse had its effect. The necromancer's enemies lay before him, drained and inert in the final grave pose, as if obeying Death on the throne. » [10]

The three central texts of the cycle deal with the events of other characters. Neither The double shadow we find the sorcerer Pharpetron and his teacher Avyctes, the only surviving pupil of Malygris, grappling with a repellent entity, erroneously evoked by them, in a story that arises in the thematic wake of The last spell and from the strong Lovecraftian tints:

« We had called her from the unfathomable depths of time and space, using a terrible formula in ignorance: and she had come at the hour she had chosen, to incarnate in the summoners as the most complete terror.." [11]

In A wine from Atlantis let's retrace the tragic epilogue of Black Falcon and its captain Barnaby Dwale from the perspective of the one lucky survivor teetotaler. Intoxicated by a bewitched royal wine, the entire crew is swallowed by the Atlantean ghost town, in a narrative in which the sleep-wake dialectic is the master.

But it is mainly in the Journey to Sfanomoë that Smith's dreamlike suggestions reach very high peaks. These pages retrace the slow exodus of the brothers Hotar and Evidon, two scientists originally from the maritime city of Lephara, who manage to abandon Poseidonis shortly before his sinking, aboard an airship built by them, to land on the planet Venus, known by the name of Sfanomoë. During the grueling journey, they face all sorts of discussions, they experiment the regret and pain that must be paid to the vanished beauty, to the shipwreck of so much splendor of the homeland more and more distant, waiting to reach the new planet, which they imagine inhabited and very developed.

Finally arrived at their destination, the protagonists find themselves immersed in a primordial and intoxicating landscape, characterized by a multitude of flowers with unprecedented shapes. In this artificial paradise, the last survivors of Atlantis lose their memory and their bodies begin to change, contaminating themselves with the local vegetation, until it becomes a single entity with the surrounding space:

« In a short time the two old men no longer had a human aspect and could not distinguish themselves from the garlanded trees that surrounded them. They died without suffering, as if they were already part of the teeming floral life of Sfanomoë, equipped with the senses and organs best suited to the new existence.. It was not long and the metamorphosis was complete, every fiber of the two bodies dissolved in the flowers. » [12]

Note:

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft Review to «Ebony and Crystal by Clark Ashton Smith»in Horror theory. All critical writings, Bietti, Milan 2018, p. 167.

- Alfred Galpin, Echoes from Beyond Space, in Giuseppe Lippi, In search of the lost worlds, in Atlantis and the lost worlds, p. XV.

- Smith has published these works separately in different magazines (including the famous Weird tales) between the end of the XNUMXs and the beginning of the XNUMXs. Later Lin Carter brought them together in a single cycle, entitled Poseidonis, published by Ballantine Books in 1973.

- Clark Ashton Smith, Atlantis, in Atlantis and the lost worlds, Oscar Mondadori, Milan 2017, p. 62.

- See: Giuseppe Lippi, In search of the lost worlds, in Atlantis and the lost worlds, p. VII.

- Ibid, p. X.

- See: Clark Ashton Smith, From a letter, in Atlantis and the lost worlds, p. 5.

- Lippi, In search of the lost worlds, p. XI.

- Francis La Manno, Clark Ashton Smith and decadence, in Beyond the Real. Lovecraft, Machen, Meyrink, Smith and Tolkien: five sculptors of universes, GOG, Rome 2020, p. 65.

- Clark Ashton Smith, Malygris's death, in Atlantis and the lost worlds, pp. 54-55.

- Clark Ashton Smith, The double shadow, in Atlantis and the lost worlds, p. 32.

- Clark Ashton Smith, Journey to Sfanomoëin Atlantis and the lost worlds, p. 20.

the truth me enchant the story I promise to releerlo, this world exists I come on a journey to the akasha is desired beautiful