The true origin of verbal language is a mystery that is lost in the mists of the most remote past of mankind. This universal and transversal theme (which is linked to that of the arcane power of the word and in particular the evocation of Divine Names) in Western civilization has been the subject of speculative and theological reflection since the times of Greek philosophy, maintaining its centrality also in the philosophical culture of the Christian Middle Ages.

di Iari Padoan

Cover: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Babel tower; Part 1 of 2

During the Western Middle Ages the philosophical reflection on the nature and origin of human language it takes place in the context of Christian philosophical-theological thought, which, through a more than millennial era, has notoriously maintained an almost total cultural hegemony. This even if, on this question (as on many others in the philosophical, scientific, artistic ...), there will be cultural contributions far from negligible coming from the Jewish and Islamic tradition, as we will be able to illustrate. To address the initial point of the question, it will be necessary to underline, once more, how fundamental the role of the Bible was for the Christian Middle Ages, how closely the theological-philosophical tradition of the time was, and how significant its role was. role of sacred book by definition, an extremely multifaceted condition due to its very essence of text.

Since the early centuries, the Christian tradition considers philosophy and theology as two areas that are deeply interconnected, but far from being placed at the same level: philosophy in the strict sense, in fact, can only be a mere preparatory path aimed at possessing the tools with which to tackle theological study. A clear hierarchical subdivision of the two disciplines is theorized right from the thought of Saint Augustine of Hippo (354 - 430), and then radicalized itself in the scholastic tradition (in particular thanks to Bonaventura da Bagnoregio and Thomas Aquinas): if theology is certainly the dominates scientiae, being at the apex of knowledge as it addresses the Divine, the whole philosophical tradition before and after the advent of Christianity can only reveal itself, at most, as a ancilla theologiae, therefore, a subjected discipline and literally at the service of the authentic knowledge of religious truth.

And, in the cultural context of the Middle Ages, for all that was known about divine revelation and the order of the world, an appeal was made to the tradition of authorities. From the verb augeo or "to grow", "fortify", "enlarge" you have the adjectives August, auto and the noun authority; for the Roman tradition, of which medieval culture is impregnated in many senses (think of the very idea of Empire, guarded by Byzantium, restored by Charlemagne and of which the Catholic Church will unofficially and extensively boast) theauthority it was what was conveyed by the greatness of the past, it was the mos Maiorum of the ancestors (and remember the apostrophe of Farinata degli Uberti to Dante: "Who but the greatest?»), And said authority it was represented by the rules established by the greats example of Tradition.

In the course of the Christian Middle Ages, therefore, the main role authorities it is taken first and foremost from the canonical books of the Bible; secondly, from the teachings imposed by historical Christianity: the thought and works of the Fathers of the Church of late antiquity and later of the great Masters university students, or the eminent figures of scholars and university professors who are also and above all important religious personalities. An example for all, in this sense, can be that of St. Albert the Great, Doctor of the Church known by the epithet of Doctor Universalis (also because he is a distinguished figure of alchemist and magician ...). All this in addition to what remained of the immense patrimony of classical sources, and therefore pagan, extensively revised and corrected on the basis of the Christian perspective according to a constant and repeated comparison with the aforementioned authority scriptural.

It is indicative, moreover, that the corpus of biblical texts is preserved and handed down in European culture, through the medieval era, with the Greek name of Ta Biblia, or "the books" by definition, constituting a universally known paradigmatic canon, which does not require further specifications. Any subject of knowledge, therefore, is evaluated and studied in the light of biblical revelation. As pointed out among others Jacques Le Goff, it is necessary to understand how deeply this authentic biblical "paradigm" was constitutive in the ideological-cultural system in which the man of the Middle Ages is inserted, and consequently the intellectual of the Middle Ages. It is in this way that, for the thinkers and great authors active in this era, it was quite natural for language to constitute a privileged subject of study. On the one hand, in fact, there were the very conditions of cultural transmission which, together with the great artistic expressions whose central role is played by the architecture of cathedrals, was almost totally entrusted to the reading and exegesis of the biblical text; on the other hand, the patristic tradition preserves the Platonic-Christian heritage of the theological vision of Jesus as Λόϒος incarnate.

Notoriously, in fact, late ancient and then medieval Christian philosophy finds the indispensable tools to understand, and make people understand, the truth revealed by Christ in most of the concepts of Greek philosophy, especially in the Aristotelian tradition but also in the Neoplatonism of the first centuries. Plato and (neo) Platonism are in fact everywhere in medieval culture (albeit "incognito" because overshadowed by the superpower ofAristotelianism, especially after the arrival in the West of Stagirita's works translated and commented on by Arab and Jewish scholars starting from the XNUMXth century), thanks to works such as those of Origen, of Agostino, of Boethius, of the very important commentary on the Timaeus written in Latin by Calcidius, up to Scholastica (especially in the context of the School of Chartres), without forgetting the importance and influence of the Islamic master Avicenna (Afshana 980 - Hamadan 1037). It is therefore this very nature of the biblical text, received as sacred Scripture and even earlier as the Word, that leads the scholars of the Middle Ages to investigate the enigmas of human language.

Ontological-linguistic problems in Genesis addressed by Christian philosophy: the Word and the Name

The interpretative effort of this theme has been concentrated for centuries in particular on the book of Genesis; this is because in its first eleven chapters there is a real speculation on origins of language and on linguistic ontology, which is articulated through two fundamental themes. The first, "fundamental" in every sense, is that of creatio caeli et terrae which takes place, in fact, through the articulation of the Divine word (Genesis I, 1-31); it is ideally connected to that of the so-called nominao rerum from Adam (II, 19-20). A few chapters later, but with a passage of many epochs according to the chronology of the biblical story, we find instead the episode that narrates the confusio linguarum of the peoples of the Earth following the attempted construction of the mythical Tower of Babel (X, XI). In these first eleven chapters (the so-called Urgescheichte, history of the origins) there are therefore considerable linguistic and semiotic reflections, which become the thematic nodes investigated by the great fathers of the church and by the major medieval commentators; the same ones on which it will be based, in the XNUMXth century, Dante's analysis in Of Vulgari Eloquentia, whose first book thus assumes the characteristics of an original commentary on the Genesis.

According to the dictates of Sacred Scripture, the aforementioned is therefore not just a word su God, but also Word di God; this is what Paul already underlined (in Th. II, 13; Ef. VI, 17 and He. IV, 12), the first great builder of the Christian doctrinal-ideological edifice. The Judeo-Christian God can in fact see himself as a "Linguistic god", both in that depositary of the Word; and because he manifested himself through writing and narration, having spoken through men and with a language that can be understood by human ears. Regarding this last point, there is a whole tradition of medieval studies on like God has actually manifested himself in the course of history, addressing the Progenitors, the Patriarchs, the Prophets up to the Apostles; whether the modalities of this manifestation occurred through celestial phenomena, or through forms of interior inspiration (as argued for example by Ugo da San Vittore in his De Sacramentis, about the language used between God and Adam) and so on.

In addition to this, patristic reflection will mostly concern itself with another philosophical-linguistic problem related to Genesis: that of Adam nomothet. The axiological Judeo-Christian myth of the Origins attributes to the Progenitor the power to name things (Genesis II, 19-20); in this way, it appears evident that Adam is subject to God as the creature to his Creator, but nature, and in particular living beings, are also subject to the power of man. For this reason the Lord presents to Adam the animals created in the previous days, and, as if to invest him with a sovereignty, he grants him the privilege of giving them a name. The biblical language, which is religious and symbolic language as well as narrative, therefore means that the name imposed on things is not a simple conceptual indication, but denotes a precise value of possession: only those who have authority he is able to give a name to a subject, and therefore to call this subject into question, to e-vocalize it.

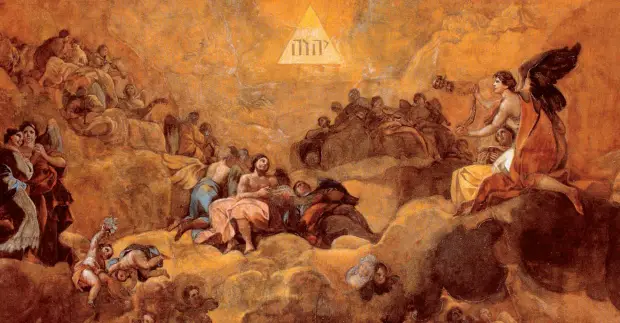

This is an almost divine power, but at the same time primarily human, the conception of which returns punctually in the most disparate traditions. It is known to be peculiar and dogmatic in the Jewish Tradition, with the concept of Tetragrammaton, the terrible divine Name composed of the four unpronounceable letters, which only relatively more recently would it have been replaced by a series of attributive names such as adonai ("The Sir"), El Shadday ("The Almighty") and above all Elohim (which essentially means "the Eternal" and also declines an important plural maiestatis), who circumvent the question by referring to God with one of his characteristics rather than by appealing to him directly. The name Elohim, as well as that of The Elyon ("The Most High"), derives from the same Semitic lexical basis of theAllah Arab, with whose invocation opens every sura of the Koran, in a ritual procedure that follows almost the same concept.

A concept, that of tremendous power linked to the evocation of divine names, already evident in the ancient times of Pharaonic Egypt (as Plutarch recalls in his De Isis et Osiris), as well as in Rome we find the tradition of the secret name of the city. This ancestral and mysterious name, whose power was to conceal the very essence of Rome, would have been handed down by Romulus himself to the pontificas later (in particular to the Salii priests, custodians of the cult of Mars but also of the most ancient deities and actually unmentionable, such as Tacita Muta) through the centuries up to the imperial age, in total secrecy. A secret broken only because of the recklessness of the tribune of the plebs Fifth Valerio Sorano, who would have revealed the aforementioned sacred name, only to be promptly executed despite the noble patrician descent, as guilty of high treason (the story, although obscure, dates back to the period of the civil war between Mario and Silla in the first century BC and is remembered by authors such as Pliny the Elder and Servius Mario Onorato).

Again, we find the same idea when we come to a Christian context, if in uttering the Sign of the Cross the Triune God in person (or rather in persona). Thus returning to Genesis IIin fact, Adam who names animals exercises one over them demiurgic power, thus giving an order to reality: precisely through language, man implements a new and personal creation, however subordinate and intrinsic to the divine Creation. Adam is like that nomothet, calls each animal "nomibus suis»,« With their names »according to the Vulgate by Girolamo. This passage of the text actually opens up yet another very delicate question, about which most medieval biblical commentators will support the paradoxical thesis of the character natural of Adam's tongue, who would have known how to attribute names to things according to their nature but at the same time arbitrarily, or on the basis of his personal agreement; This is, for example, the opinion of John of Salisbury (Salisbury 1110-Chartres 1170) and of Meister Eckart (Thuringia 1260-Cologne 1327), the father of the great German mystic, who discusses it in his text Exposure in Genesis.

Particularly interesting and indicative in this regard is the question of woman's name: after the passage on the "zoological nomenclature", the Genesis tale narrates that Adam actually pronounces the first words (at least those reported in the text), and does so by referring to his partner (Genesis II, 21-22). In fact, it is only after the Fall and the double condemnation of the Progenitors that we read that the woman is called Eve (Hawwah), while until then she had only been referred to as "the woman" (virago in the Vulgate, which not surprisingly, being the literal feminine of vir, is the literal translation of Hebrew issah, feminine of ish, "man"). Precisely that of Eve would therefore be a consequential to the nature of what she designates (just as the name of Adam denounces her origin from clay, adamah): Hawwah is derived from the verbal root hajah, "to live", and it is evident that only after the condemnation to mortality and the consequent female faculty of generating life, Eve takes the name associated with her universal motherhood.

La original language (Adam) e le historical languages (the Tower of Babel)

At this point, we come to the other great problem of this first "linguistic side" of Genesis, a decidedly fundamental and equally unsolvable problem: what language did Adam speak? Necessarily there must have been a primordial idiom, and the scholar Massimiliano Corrado underlines how the idea of a monogenesis of languages is of a specific character to the Judeo-Christian civilization: from the monotheistic assumption it would follow the concept of a unique and perfect primeval language, being the uniqueness component of perfection. The language of Adam, consequently, is seen not only as ursprache (original language), But also as hierolanguage (sacred language): any other subsequent language, having been born of a differentiation and a multiplicity, would have lost this perfection, being neither unique nor perfect, and could at best only partially reproduce the features of the original one.

This is, therefore, the dominant doctrine in medieval hermeneutical, theological and philosophical thought in the face of this question set out in the Scriptures. A position supported by almost all of the Fathers of the Church, that they believed, therefore, that that language could only be Hebrew, which in this way assumed a chronological and theological priority over every other human language, of which the most ancient matrix was revealed. Only the language of the people of Israel in which the Old Testament is written, therefore, was the original language, also because, logically, it preceded the Babelic guilt: and this is the vision to which personalities of the caliber of Jerome adhere (Epistle XVIII), Augustine (De Civitate Dei, XVI), Isidore of Seville (Etymologiae, IX, 1), Venerable Bede (Rerum Natura), Peter Comestore (Scholastic history). According to all the authors indicated (unlike Gregory of Nyssa, a XNUMXth century Greek theologian influenced by Origen and Platonism, who argues that if God and Adam ever talked, such communication certainly did not take place in Hebrew) a strong link between the episode of Adam nomothet and the one narrated in Genesis X-XI, or that of the attempted construction of the Tower of Babel and the consequent linguistic dispersion.

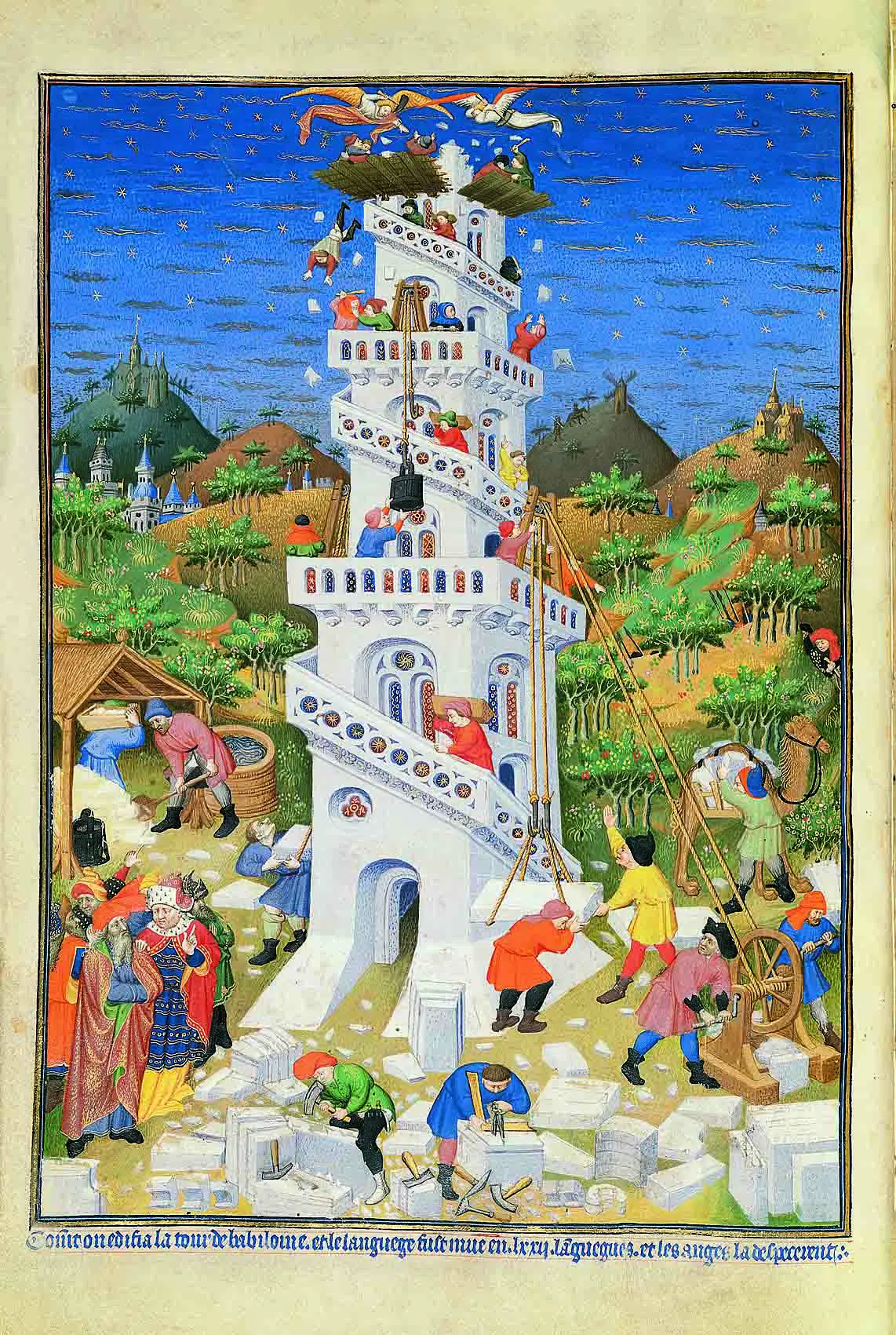

The linguistic theme is then taken up by the Genesis in this chapter, in which we use to see a confirmation of the original character of the (iero) Hebrew language, which remained unique and incorruptible from Adam to the Babel builders. Furthermore, the Babel myth provided an explanation for the evident fact of the mutability of human languages through time and space: as is known, it is said of how, after the Flood, the ancient peoples from the East settled in the plain of Sennaàr (located south of Mesopotamia along the course of the Tigris, between Babylon and Assyria in the North), where, at the urging of the giant-king Nembrot or Nimrud, they begin the construction of a vast city, whose tower will have to rise up to the sky (XI, 1-4) . There legendary figure of Nimrud it is perhaps vaguely inspired by the historical one of the emperor Sargon of Akkad (unifier of Mesopotamia around 2280 BC), and moreover bears yet another "natural" name whose lexical root would indicate the same as the verb himrid, "Rebel". Dante, in the Comedy, will meet "Nembròt" among the Giants in the XXXI canto of theHell; the character, "for which badly understood / even a language in the world is not used"And which is not by chance expressed in incomprehensible words, will also be mentioned, as we shall see, in XXVI of XNUMX. Paradiso.

The Genesis text underlines how all humanity gathered there for the enterprise actually speaks the same language (XI, 1), a state of affairs that changes radically after God, understandably upset by the initiative, causes a profound change in the human linguistic code: the reckless builders no longer understand each other, and then scatter around the world. In the'image of the city-tower obviously relives the memory of Babylon (the biblical author considers it a "motivated" name, making it derive from the Hebrew verb Balal, "Confuse", while the Akkadian root is now more confirmed Bab-ilu, "Gate of the Gods") with its ziqqurat, the most famous towers of the ancient world.

Apart from the rather bad memory that the Bible generally records of the city and kingdom of Babylon (see especially the books of Daniele need Isaia, untilApocalypse of John), a legacy of centuries of Israel's wars against the Assyrians and of the first destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in the Neo-Babylonian period (VII-VI century BC), patristic and medieval religious exegesis interpreted the construction of the Tower as a sign of Promethean challenge to the sky, in an attempt by human hubris to equal divine power.

Not to mention another problem that is far from indifferent, namely that of the actual narrative and chronological contradictions that are found between Genesis X and XI: in fact in the chapter preceding the Babel episode, arguing about the descent of the sons of Noah after the flood, there are clear references to the fact that languages spoken by the three Noachite bloodlines yes they were already differentiated (Genesis X, 5 and X, 31). These are discrepancies due to the evident composite structure of the biblical text (but not so evident to the medieval reader of the Pentateuch, who traditionally attributed the writing of the work to Moses himself), which were necessarily interpreted according to the times and positions theological-philosophical.

Returning to the main question, theauthority patristics had therefore generally accepted the belief that Hebrew was the language of primeval humanity, generally since, even here, the interpretation of the subject varies according to the author who deals with it. If Girolamo, in the fourth century, translated the Old Testament not from the Greek of the Bible of the Seventy but directly from Hebrew (in a historical moment in which the knowledge of this language is increasingly fading), Augustine, a man of culture and depth frightening and the greatest representative of Christian thought in the moment of dissolution of the Western Empire, it testifies to a paradoxical linguistic and exegetical situation. This is because the aforementioned Christian thinking is based on an Old Testament written in Hebrew and a New written mostly in Greek; the problem of the bishop of Hippo in his role as interpreter of the Scriptures, a divine text by definition ("semblance of God", as Augustine defines them) is to understand what the divine text means exactly, and of that text he has only Latin translations, without having a deep knowledge of either the Greek of the Gospels or the Biblical Hebrew.

Showing himself in this way, as Umberto Eco, champion of biblical hermeneutics but certainly not of philology, wrote, Augustine also shows no need to find or try to reconstruct the language spoken by Adam, being at ease with his Latin now become (also thanks to him) the great sacred language of Western Christianity. And, a couple of centuries later, Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636) will argue in Etymologiae IX, 1, his conviction that in each case of sacred languages there are three, since the inscription placed over the cross was trilingual. From a Christian point of view, therefore, that would be enough for the believer, says Isidore; the great doctor of the Church also underlines, referring to Gregory of Nyssa, how it would now be difficult to establish which language Adam actually spoke or even the Lord himself when he enunciated the fiat lux.

(follows the part 2)

Bibliography:

- The Holy Bible, edited by the Italian Episcopal Conference, CEI, Rome 2001

- Various authors, Garzanti Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Garzanti, Milan 1988 AA.VV. Encyclopedia of Religions, Garzanti, Milan 1989

- Various authors, The deformed idea. esoteric interpretations of Dante, curated by Maria Pia Pozzato, Bompiani, Milan 1989

- Nicola Abbagnano, Giovanni Fornero, Protagonists and texts of philosophy, volume A tomes 1-2, Paravia / Bruno Mondadori, Milan 2000

- St. Augustine, The city of God, curated by Domenico Marafioti, Mondadori, Milan 2015

- Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, edited by Daniele Mattalia, Rizzoli, Milan 1960

- Dante Alighieri, Of Vulgari Eloquentia, edited by Giorgio Inglese, Rizzoli, Milan 1998

- Domenico Casalino, The secret name of Rome. Metaphysics of Roman times, Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome 2003

- Conrad, Maximilian, Dante and the question of the language of Adam (De vulgari eloquentia, 1. 4-7; Paradiso, 26. 124-38), Salerno Publisher, Salerno 2010

- Sandra Debenedetti Stow Dante and Jewish mysticism, Giuntina, Florence 2004

- Umberto Eco, The search for the perfect language in European culture, Laterza, Bari 1993

- Rene Guenon, Dante's esotericism, Adelphi, Milan 2001

- Rene Guenon, Symbols of sacred science, Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome 1975

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologies or origins, edited by Angelo Valastro Canale, Utet, Turin 2006

- Marco Mancini, The rejection of linguistic diversity, in Giuseppe Longobardi, edited by, The languages of the world. The sciences notebooks 108 of June 1999, Le Scienze spa, Milan 1999

- Gabriel Mandel Khan, Hebrew alphabet, Mondadori-Electa, Milan 2012

- Gianni Pilo, Sebastiano Fusco, The kabbalistic symbolism of the Golem, in Gustav Meyrink, The Golem and other tales, Newton & Compton, Rome 1994

- Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah and its symbolism, Turin, Einaudi 1980

A comment on "Considerations on the question of hierolanguage in the Middle Ages (I)"