[Extract from the graduation thesis Recognition of the rights of the Native Peoples of Canada2015]

Le First Nations of Canada use the oral tradition to record information considered to be of primary importance, which is collected and shared through a form of literature which holds memory and the spoken word in high regard. Oral transmission allows the normative-behavioral systems of indigenous populations to be subjected, day after day, generation after generation, to continuous creation. A strong point of this methodology is the possibility of reinterpreting traditions in such a way as to come to terms with the needs of the contemporary world, without losing the truth or principles on which the stories are based. Rather, the need for continual modification is based on the understanding that the social context is continually changing, and consequently requires a constant reinterpretation of some of the narrative elements. The fluidity of the tales of First Nations it reflects the attempt to make the deepest sense of the narratives current, adapting it from time to time to the needs of listeners.

Le First Nations of Canada use the oral tradition to record information considered to be of primary importance, which is collected and shared through a form of literature which holds memory and the spoken word in high regard. Oral transmission allows the normative-behavioral systems of indigenous populations to be subjected, day after day, generation after generation, to continuous creation. A strong point of this methodology is the possibility of reinterpreting traditions in such a way as to come to terms with the needs of the contemporary world, without losing the truth or principles on which the stories are based. Rather, the need for continual modification is based on the understanding that the social context is continually changing, and consequently requires a constant reinterpretation of some of the narrative elements. The fluidity of the tales of First Nations it reflects the attempt to make the deepest sense of the narratives current, adapting it from time to time to the needs of listeners.

La law of reciprocity

La law of reciprocity

In the native worldview, fundamental importance is reserved for the principles of respect, mutual exchange and reciprocity. For example, the oral history handed down in the Tlicho Nation, whose people are known as the Dene People, it is entirely structured on a series of agreements, each of which “has historically served to resolve a conflict”.

These agreements are not limited to agreements with white settlers and miners: cosmology and Tlicho mythology, narrated by the elders and native leaders, they speak of five main agreements aimed at establishing as many interdependent relationships with as many categories of actors. These five pacts divide the history of the nation into five historical eras, the first of which coincides with prehistory. According to the Tlicho cosmology, one of the first agreements was made with the world animal, as the natives believe they have the responsibility to safeguard the environment and to grant their protection to animals in order to ensure their survival. For this reason, the Denis show such respect for the natural world that it can be defined as sacral: before picking any type of herb or root, which will then be used according to traditional uses, they turn to it as if a conscious spirit permeated it - which they actually believe - a spirit able to listen to the requests, justifications and excuses of those who prepares to eradicate it. Likewise, even before leaving for a joke of hunting or following the killing of game, the Denis usually establish a sacred relationship with the spirit of the animal species towards which the hunt is directed, in order to keep alive a relationship of interdependence e mutual exchange which, otherwise, would risk being compromised forever. This philosophy of life is also easily found in the native custom of "honoring the earth" (pay the land), a practice that has spanned the centuries and which has remained in vogue even in the historical era of the first mining extractions alongside the white settlers and which continues today.

It is clear, therefore, how the most ancient myths of creation became for the Dene population the foundation of the normative system: the obligation that, at the dawn of time, the natives recognized they had towards the natural world and in particular towards that animal becomes, for example, a touchstone for all the agreements that will come later, that is to say those with neighboring populations or with white settlers. And, in fact, the most recent eras, in which the value ofinterdependence is kept according to the example mythical and applied to relations with other human societies, those of tribal neighbors and the latest white arrivals. However, the latter, historically called by the natives with the nickname of kweti (literally: "those who seek minerals"), they have never been able to fully understand the logic of reciprocity on which the entire social system is based and consequently also the native commercial system. In fact, while the natives possessed an informal economy, based on barter and mutual exchange relationships - of information as well as goods - the kweti they have always appeared to be very reserved in their relations with the native population, reluctant to share with them the information and profits of what they managed to obtain from Canadian land, also and above all thanks to the precious knowledge and material help of the natives. History reveals how native peoples have always felt a real one obligation towards newcomers: a responsibility to share one's skills and knowledge, in order to establish a peaceful coexistence based, once again, on the principles of reciprocity and mutual respect.

It is clear, therefore, how the most ancient myths of creation became for the Dene population the foundation of the normative system: the obligation that, at the dawn of time, the natives recognized they had towards the natural world and in particular towards that animal becomes, for example, a touchstone for all the agreements that will come later, that is to say those with neighboring populations or with white settlers. And, in fact, the most recent eras, in which the value ofinterdependence is kept according to the example mythical and applied to relations with other human societies, those of tribal neighbors and the latest white arrivals. However, the latter, historically called by the natives with the nickname of kweti (literally: "those who seek minerals"), they have never been able to fully understand the logic of reciprocity on which the entire social system is based and consequently also the native commercial system. In fact, while the natives possessed an informal economy, based on barter and mutual exchange relationships - of information as well as goods - the kweti they have always appeared to be very reserved in their relations with the native population, reluctant to share with them the information and profits of what they managed to obtain from Canadian land, also and above all thanks to the precious knowledge and material help of the natives. History reveals how native peoples have always felt a real one obligation towards newcomers: a responsibility to share one's skills and knowledge, in order to establish a peaceful coexistence based, once again, on the principles of reciprocity and mutual respect.

However, it is impossible for us to fully understand the logic of native reciprocity if we limit ourselves to understanding the term obligation starting from our Romanistic background. If, in fact, for us Westerners the relationship of obligation mostly binds two actors - or rather, two parties - who, finding themselves in conflict for the obtaining of a resource, agree through a written agreement on their respective reciprocal rights and duties, on obligations and on the legitimate expectations that some can boasting towards others, in the native view the relationship of obligation has a much wider extension.

For native populations, in fact, every bond relationship that comes recognized and handed down does not derive from a stipulation tout court only with the other contractual party, but must take into account the relationships of interdependence and reciprocity that indissolubly bind man - both native and non-native - to the rest of the world, and therefore to the natural world, to the earth, to the animal kingdom. In other words, every pact concluded by the natives and every obligation recognized by them, whether towards the natural world or towards other human societies, is nothing but a reflection of theoriginal obligation, that towards the entire universe, intended as a stage in which certain forces - if you will, spiritual - continuously and uninterruptedly since the dawn of time they manifest themselves according to the law par excellence, that one natural e primal, which in the first place is governed precisely by the principle of reciprocity.

The Denis, as well as all native American peoples, recognize that it is not possible to obtain something from the natural cycle without "paying the price": hence the multitude of prayers, communications with the natural world and offerings to the earth.

Le Big Stories

Le Big Stories dei Dene deal extensively with this conception, codifying in mythical tales the right relationships of reciprocity that must be established with the rest of the world.

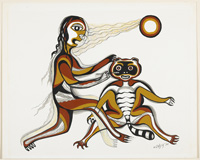

The Nanabush cycle, trickster of Tlicho mythology - a spirit sometimes also represented in animal form, identified with the skunk, the raccoon or the porcupine - is a remarkable example of teaching ancestral inspired by this worldview. It is the symbol, or rather the personification of the lack of respect towards the supreme logic of reciprocity towards nature and the cosmic order. In several myths, the character of Nanabush is attributed the original blame for causing an imbalance, harmful and potentially fatal, within the complex of forces that make possible the survival of the world as it must be, as it has always been, from dawn of time.

The Nanabush cycle, trickster of Tlicho mythology - a spirit sometimes also represented in animal form, identified with the skunk, the raccoon or the porcupine - is a remarkable example of teaching ancestral inspired by this worldview. It is the symbol, or rather the personification of the lack of respect towards the supreme logic of reciprocity towards nature and the cosmic order. In several myths, the character of Nanabush is attributed the original blame for causing an imbalance, harmful and potentially fatal, within the complex of forces that make possible the survival of the world as it must be, as it has always been, from dawn of time.

In these stories, Nanabush is the one who, sinning from excessive gluttony, exceeds in hunting beyond all limits allowed by natural law, thus decreeing the death of almost all of the wooded game, causing a breakdown of the pre-established order and the delicacies. reciprocity mechanisms that govern it. If we wanted to try to translate Nanabush's sin according to our Western background, probably the closest concept we could refer to is the Hellenistic one of hybris (in ancient Greek ὕβϱις, translatable as "arrogance"), the supreme guilt of the hero who, trusting only in himself, in his own inner strength and in the power of reason, lacked respect for the Divinity, the Supernatural, going irremediably to meet the Nemesis (divine punishment) and to ruin.

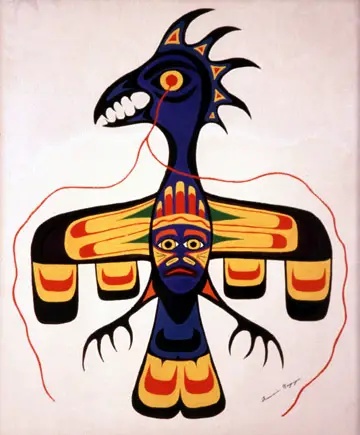

In another story, the crow plays the role of trickster but, unlike the Nanabush tale, in this case it plays the role of a teacher for the native population. Indeed, it should be mentioned that the figure of trickster in these mythologies he is always double, presenting himself on the one hand as the one who destroys the known world and the established order, on the other as the one who creates a different one: in the latter light the trickster appears as a divine teacher towards ancestral humanity, as the one who, although with sometimes amoral or apparently crazy behaviors, gives precious teachings to humans wise enough to understand them.

The crow - we said - in this narration of the Anishinabek takes advantage of the migration of a large number of fawns, moose and caribou to gather them within its borders. When the Anishinabek, worried about the sudden disappearance of such a large number of game heads, learn of what is happening, they wage war on the crow. But it is the representative of the fawns who explains to the natives how the situation really is: they, and with them the moose and the caribou, have spontaneously chosen to settle in the territories of the crow under its protective wing, as "the crows have treated us better than you humans have ever done, at the time we shared the territory with you ”. When the incredulous Anishinabek ask the fawn how their behavior offended them, it sadly replies: “You have wasted our flesh, desecrated our bones, dishonored us and yourselves. Without you we can live, but you cannot live without us ”. At this point, when the mortified natives ask how they can restore the original relationship with the animal kingdom, the fawn dispenses these advice: “Honor and respect our lives and our essence, both in life and after death. Stop behaviors that offend spirits. Don't waste our meat. Preserve the fields and forests as they are our home. To show your resentment of what has happened and to ensure that future generations do not forget this teaching, from now on adopt the custom of leaving a tobacco leaf in the place where you will kill one of us for your supply. Gifts are of primary importance to rebuild the relationship between you and us ". At this point in the narrative, the Anishinabek promise to follow the fawn's lesson, and the ravens allow the game to return to their territory.

The story just reported is a classic example of a founding myth of native populations: from this original obligation all the others follow accordingly, as reflections of a truth ancestral that, thanks to the intercession of the forces of nature - always represented halfway between the spiritual and the physical world - the native man was able to experiment on his skin and fully understand, aware that he can no longer ignore this lesson if it is up to him the survival of its own species.

The myth of Nanabush as well as that of the crow and the wild game represents a precedent of primary importance regarding the governance of natural resources by the natives. They convey the principles that the human consortium must respect and follow in order to be able to enter the circle of reciprocity that governs everything, the natural world as well as the spiritual one - which, moreover, in the native vision are nothing more than two sides of the same coin.

If the Anishinabeks stopped following and respecting these promises, this way of relating to the environment, the inevitable consequence would be the definitive disappearance of these resources; and while these resources may continue to exist without our exploitation, on the contrary the human consortium would have no future without them.

Bibliography:

-

Michael Asch, Home and Native Land: Aboriginal Rights in the Canadian Constitution (Methuen, Toronto, 1984)

-

John Borrows, Recover Canada: The Resurgence of Indigenous Law (University of Toronto Press, 2002)

-

Ginger Gibson MacDonald, John B. Zoe and Terre and T. Satterfield 2013 Satterfield, "Reciprocity in the Canadian Dene Diamond Mining Economy " in Emma Gilberthorpe and Gavin Hilson, Natural Resource Extraction and Indigenous Livelihoods: Development Challenges in an Era of Globalization (Ashgate, 2013)

2 comments on “The oral tradition of the "Big Stories" as the foundation of the Native Peoples Law of Canada"