di Marco Maculotti

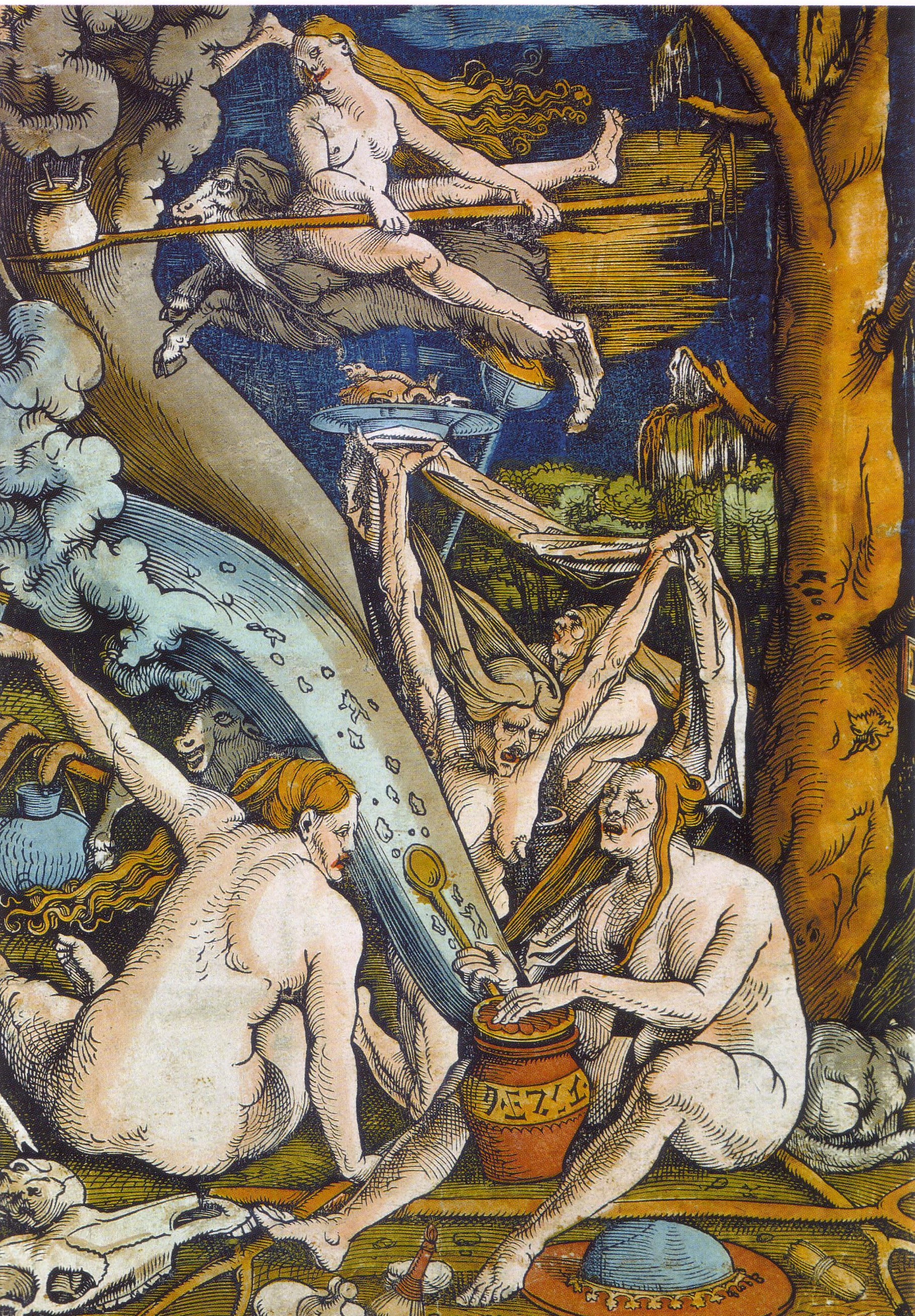

cover: Luis Ricardo Falero, “Witches going to their Sabbath", 1878).

Carlo Ginzburg (born 1939), a renowned scholar of religious folklore and medieval popular beliefs, published in 1966 as his first work The Benandanti, a research on the Friulian peasant society of the sixteenth century. The author, thanks to a remarkable work on a conspicuous documentary material relating to the trials of the courts of the Inquisition, reconstructed the complex system of beliefs widespread up to a relatively recent era in the peasant world of northern Italy and other countries, of Germanic area, Central Europe.

According to Ginzburg, the beliefs concerning the company of the benandanti and their ritual battles against witches and sorcerers on the Thursday nights of the four tempora (Her hand, imbol, Beltain, Lughnasad), were to be interpreted as a natural evolution, which took place far from the city centers and from the influence of the various Christian Churches, of an ancient agrarian cult with shamanic characteristics, widespread throughout Europe since the Archaic age, before the spread of the Jewish religion - Christian. Ginzburg's analysis of the interpretation proposed at the time by the inquisitors is also of considerable interest, who, often displaced by what they heard during interrogation by the benandanti defendants, mostly limited themselves to equating the complex experience of the latter with the nefarious practices of witchcraft. Although with the passing of the centuries the tales of the benandanti became more and more similar to those concerning the witchcraft sabbath, the author noted that this concordance was not absolute:

"If, in fact, the witches and sorcerers who meet on Thursday night to give themselves to" jumps "," fun "," weddings "and banquets, immediately evoke the image of the sabb - that sabb that the demonologists had meticulously described and codified, and the inquisitors persecuted at least since the mid-400th century - nonetheless exist, among the gatherings described by benandanti and the traditional, vulgate image of the diabolical sabbath, evident differences. In these cEverywhere, apparently, homage is not paid to the devil (in whose presence, indeed, there is no mention of it), faith is not abjured, the cross is not trampled, there is no reproach of the sacraments. At the center of them is a dark ritual: witches and sorcerers armed with sorghum reeds who juggle and fight with benandanti provided with fennel branches. Who are these benandanti? On the one hand, they claim to oppose witches and sorcerers, to hinder their evil designs, to heal the victims of their hexes; on the other hand, not unlike their presumed adversaries, they claim to go to mysterious nocturnal gatherings, of which they cannot speak under pain of being beaten, riding hares, cats and other animals. "

—Carlo Ginzburg, "I benandanti. Witchcraft and agrarian cults between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries», Pp. 7-8

The "camisciola" and the call of the angel

Ginzburg immediately attests (The benandanti, p.23) that the benandanti constitute, from what emerges from the acts of the inquisitorial processes, a real sect, militarily organized around a captain and bound by a bond of secrecy, which however the members continually break, for loquacity, boast or to indulge the inquisitors. According to one of them, named Moduco, "All those who are born in clothes are part of this "company" ... and when they reach the age of twenty they are called precisely like the drum that calls the soldiers, and we must go"(B. p.11). The initiation of the benandanti takes place at a precise age, corresponding approximately to the reached maturity: Moduco at 20, Gasparutto at 28). Ginzburg also adds that, as in an army, after a certain period (10, 20 years) "one is freed from the obligation to go to fight at night" (p.25).

The followers of this sect are linked above all by a common element: all of them were born with the "camisciola", that is, wrapped in the amniotic membrane. This smock is believed to protect soldiers from blows, ward off enemies, even help lawyers win lawsuits. That children born with shirts were condemned to become sorcerers is a living tradition in the folklore of many parts of Italy, including Friuli and Istria (p.25); moreover, in some European traditions, and not only, the shirt is considered as the "seat of the external soul": a bridge of passage, a link between the world of the living and that of the dead. In Denmark it is thought that those born with a shirt have the ability to see the dead (p.93). In the tales of the benandanti the little shirt is not spoken of as a demonic gift, but rather a beneficial aura is reserved for it. Let's say with the Moduco that there are apparently "sorcerers which are boni, called vagabondi and in their language benandanti, who prevent evil, while others they do it"(P.5). Another benandante, Gasparutto, relates his being born dressed with the apparition of the angel who will introduce him into the company of the benandanti: "About a year before that angel appeared to me, she gave me a fireplace with which I was born, telling me that she had had her baptized with me, and that she had had them said over nine masses, and blessed it with some prayers. et evangelii; and she told me that I was born benandante, and that when I was grown up I would go out at night, and that I would hold her and carry her, that I would go with them benandante to fight with the strigoni"(P.24).

When asked by the inquisitor who had taught him to enter this company of benandanti, Gasparutto replied: "The angel of heaven ... at night, in my house, and it could have been four hours at night on the first sleep ... an angel all of gold appeared to me, like those of the altars, and called me, and the spirit went out ... he called by name saying: "Paulo, I will send you a benandante, and you must go and fight the fodder ..." I replied "I will go, and I am obedient""(P.15). Even Moduco seems to have lived the same initiatory experience and he too relates the shirt to the apparition of the angel: "A certain invisible thing appeared to me in the background, which bore the resemblance of a man, and it seemed to me that I was sleeping and did not sleep, and it seemed to me that it was one of Trivignano, and because I wore that camisciola that I was born around my neck, and it seemed to me that I would say: “you have to come with me because you have something of mine"". There is more: the shirt, a distinctive sign of the benandante, once lost by the Moduco prevents him from going out at night, to go to the company conferences, since "those who have a camisciola and do not wear it are not in vain"(P.18). Gasparutto tells the inquisitor that, when the angel called him, "the spirit came out, because in the body it cannot speakAnd claims to have seen the angel "every time he went out, because he always came with him" (p.16). Still according to Gasparutto, the angel of the benandanti is "beautiful and white", While that of the sorcerers"he is black and he is the devil"(P.17).

The benandanti and the ancient fertility cults

Behind the stories of these mysterious conferences and nocturnal battles we clearly see a fertility rite emerging, punctually modeled on the main events of the agricultural year: the four tempora. The benandanti armed with fennel clubs fight against witches and sorcerers armed with sorghum clubs "for the love of the snakeOr to ensure the fertility of the fields and the abundance of future crops for the community. It is an agrarian rite which remained extraordinarily vital almost at the end of the 500th century, in a marginal area, less affected by communications, such as Friuli, as Ginzburg points out (p.36). The author continues:

"The benandanti go out on the night of Thursday of the four tempora: in a holiday, that is, coming from an ancient agrarian calendar and belatedly become part of the Christian calendar, which symbolizes the seasonal crisis, the dangerous transition from the old to the new season, with his promises of sowing, harvesting, harvesting and harvesting. It is then that the benandanti go out to protect the fruits of the earth, the condition of the community's prosperity, from witches and sorcerers, that is, from the forces that occultly undermine the fertility of the fields. "

Quoting the testimony of Moduco: "I sleep well because I go with the others to fight four times a year, that is, the four tempora, at night, invisibly with the spirit and the body remains; and we go in favor of Christ and the devil's witchers, fighting one another, we with fennel clubs and they with sorghum reeds. And if we remain victors, that year is abundance, and losing is famine in that year"(P.10).

The therapeutic virtues of fennel were known in popular medicine, as well as the power to keep witches away (Moduco states that benandanti eat garlic and fennel, "because I sleep against the strigoni») While Ginzburg hypothesizes the choice of sorghum as a witch's weapon, identifying it with the broom, their traditional attribute (p.39). The connections between the nocturnal battles described by the benandanti and the ritual disputes between Winter and Spring that were represented, and still are represented, in many areas of central-northern Europe, and even more ancient rites, such as that of the expulsion of Death, are clear. , or of the Witch—the Giöbia which is still burned at the stake in Lombardy and Piedmont on the last Thursday of January—or again, in Celtic culture, of the struggles between the holly god (King of the Waning Year and darkness) and the god of the Oak (King of the Growing Year and light). In some areas of Switzerland, the ceremony of the expulsion of Winter takes place on XNUMX March, accompanied by a ritual battle between two groups of young people, practiced "to make the grass grow" [cf. Cosmic cycles and time regeneration: immolation rites of the 'King of the Old Year'].

In southern Germany, during the days of the four tempora, processions are held through the fields, aimed at obtaining prosperous harvests from God. In Tyrolean folklore we find the Perchtenlaufen, rites that on certain occasions see the contrast of two ranks of peasants, one masked by Perchte (the Germanic goddess of fertility) "beautiful", the other by "ugly" Perchte, who chase each other waving whips and wooden sticks (p .89) [cf. The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany]. A similar rite is performed by the Inuit Eskimos: as winter alternates, two groups, formed respectively by people born in winter and those born in summer, compete in strength: if the second group wins, you can hope for a good season (Frazer, The golden branch, p.99). The anthropologist Marjia Gimbutas, researcher of the ancient matriarchal cults, speaks of "rites connected to the burial of the Old Year" and centered on the "Old Lunar Witch" which were celebrated in the Archaic age in the sanctuary of Artemide Brauronia, where the myth of Iphigenia (The language of the goddess, p.313).

Lethargy, ointments and seizures

Although the benandanti admit that they go to conferences with "spirit" alone, they nevertheless never questioned the reality of such experiences. Everyone claimed that, before going to conferences, which they reached on the back of an animal (hares, cats, roosters, beaks), they fell into a state of profound prostration, catalepsy (Ginzburg calls them "ritual lethargy"). In some cases—not, however, in those of Moduco and Gasparutto—the use of ointments is also recorded to allow the spirit to leave the body and go to these conferences, just as it is well known that witches did to go to the sabbath. Ginzburg cites the Spanish theologian Alfonso Tostado (mid-400th century), who noted that witches, after having pronounced certain formulas, smeared their temples with datura-based ointments (stramonium) and fell into a deep sleep, which rendered them insensitive even to fire or wounds; but, once awakened, they claimed to have gone to distant places, to meet with other companions, feasting and flirting (p.27).

Ginzburg, while partially accepting the hypothesis that witches and benandanti suffered from psychic pathologies (epilepsy et similia), flatly denies that it is possible to explain their beliefs and their nocturnal experiences by reducing everything to the scope of the disease: this is because "the alleged hallucinations, instead of being located in an individual, private sphere, have a precise cultural consistency" (p.29 ). In other words, the experiences that witches and benandanti narrated to the inquisitors were all based on a very precise mythology, too precise to allow these experiences to be branded as simple hallucinations of the individual. According to the author—and we are of the same opinion—the fact that these experiences were caused by the action of drug-based ointments, or due to epileptic seizures, or even obtained with the help of particular ecstatic techniques, does not allow us to decipher the problem of benandanti and their beliefs, which "It must be resolved in the context of the history of popular religiosity, not of pharmacology or psychiatry" (p.30).

Also according to Galli, like Ginzburg, the question of witchcraft cannot be analyzed solely as pathology, superstition or fantasy, but it was actually an "expanding movement, a real alternative culture translating into behaviors, with ancient roots ( the Matristic civilizations, the Bacchantes, the Gnostics), re-emerging in specific conditions (the crisis of the Church, the resumption of magical-astrological beliefs) ", adding that this movement was fought" because it had cultural and social roots, because without defeating it [... ] the "modern age" could not have been such, with its own values "(Mysterious West, p. 170). Galli adds that "the devil is the Dionysus of witches", the sabbaths are an update of the maenad gatherings and "the same relationships with animals are linked to a tradition that has the antecedent in Pasiphae and its Cretan myth, as an echo of a period in which the promiscuity of the human being in nature was normally experienced "(p.173) [cf. From Pan to the Devil: the 'demonization' and the removal of ancient European cults].

Henry Kamen also thought so (The Iron Century. 1550-1660, pp. 325-326):

“Popular superstition had nothing more complicated than folk magic, the black and white magic of rural communities. […] The moment when common European folk magic became irrational was when the devil entered history. It was when the doctrine of the Sabbath began to be seriously considered, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, that the problem of witchcraft really took shape. [...] The ancient popular magic had by now extended into a diabolical threat and as diabolical the theologians intervened with their observations. "

Diana's company

Ginzburg points out that, in Modena, the first hints of witches' nocturnal conferences concern not the adoration of the devil but the cult of a mysterious female divinity, Diana, present in northern Italy at least since the end of the 300th century. It will be necessary to wait until 1532 to encounter tales of the Sabbath including descriptions of desecrated hosts, trampled crucifixes or couplings with demons; however, in this context the figure of Diana as the supreme "abbess" of the nocturnal meeting will remain present, albeit transformed (p.46). Margaret A. Murray is of the opinion that the witch hunt was actually the persecution that the Roman inquisition plotted against the survivors of ancient pagan cults in danger of extinction: it defines the "cult of Diana" as what it presents as the religion of witches (who would worship the "horned god"); and "ride of Diana" is defined as the gallop of the witches in the air, to which the Canon episcopes, probably a Frank capitular of Ludwig II of 867 (Gauls, Mysterious West, p.158). According to Murray, "the document, while demonizing the pagan superstition that caused some women to fly in the night following Diana, expresses skepticism about the real possibility of such an event." In the Canon of Reginone (around 900), the goddess of witches takes the name of Herodias, whose first hints were in Verona. According to Giorgio Galli, "the refutation of the existence of a real" god of witches ", the horned goat transformed into a devil, can be valid if one thinks of the purely symbolic value of a figure that has many similarities with Dionysus and the satyrs" (p.156).

The Dominican J. Nider (XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries) reported that individuals who claim to have been transported to Herodias' nocturnal conferences, "having come to their senses after a period of swooning, tell extraordinary things about souls who are in purgatory or hell. , on stolen or lost objects, and so on "adding that, during their ecstasy," they do not even feel the burning of a candle flame "(The Benandanti, p. 66). Tales of this kind cannot fail to bring to our mind the reports of shamanic experiences from all over the world, during which the shaman accesses the lower and higher worlds, recovers lost souls, converses with the souls of the dead and finds stolen objects or lost.

The goddess of witches and the night procession

Ginzburg, starting his reflection from the proverbial "flight of the witches", attests how this belief in nocturnal rides had a notable diffusion in medieval Europe. At the head of this nocturnal procession is Diana or Herodias, replaced in the Germanic areas by Perchta and Holda, Germanic deities of life and death, goddesses of vegetation and therefore of fertility, but also of the moon and night. Emanuela Chiavarelli connects Perchta to «Berctha, the archaic progenitor of the Germans, the divine spinner whose name refers both to Berta from the" great feet ", Arthur's mother, and to the homonymous parent of Odino-Wotan, the Berta celebrated on the 2nd January" (Diana, Harlequin, p.122). Diana-Hecate, in Greek-Roman mythology, was also followed in her nocturnal wanderings by a host of restless dead: the prematurely dead, the children who died prematurely, the victims of violent death. The aforementioned Chiavarelli names an ecclesial document, the Chronicum of the Abbot Reginone of Prün, who preaches the rejection of the dianaticus, pagan ritual in which the goddess Diana "goes around at night with her host", an army of souls—Of women who have died in childbirth- and of witches (p.25). Ginzburg, in another work of him (Night story, p.66), reports the document verbatim, which reads:

«We must not be silent that certain wicked women, who have become followers of Satan, seduced by the fantastic illusions of the demons, claim to ride the night over certain beasts together with Diana, goddess of the pagans, and a great multitude of women; to travel great distances in the silence of the deep night; to obey the orders of the goddess as if she were their mistress; to be called on certain nights to follow her. "

But it is above all Chiavarelli, in her search for the cults of archaic Europe, who speaks extensively of the goddess Diana-Artemis, Lady of the Animals, who "emerges in her role as queen of an ancient ecstatic cult centered around a mysterious" society nocturnal "". With the decline of ancient religion and the advent of Christianity, Diana took on "the appearance of a sort of fairy-maga—" the woman of the bon zogo "- indifferently called Diana, Hera, Hecate, Herodiana, Herodias, Venus, Frau Venus , Abundia, Dame Habonde, Bona Dea, Sibilla, Madonna Oriente, Holda, Hölle, Helle, Richella, Pertcha ... who, in certain periods (usually the four tempora of the solstices and equinoxes), wanders at night with his flying army " (Diana, Harlequin, p.27). To this infinite string of names, Chiavarelli also adds that of Dana, goddess of royalty and ancestor of the Celtic peoples called Tuatha Dé Dana ("the people of Dana"), who «not only remembers phonetically and semantically Diana, [...] but it was celebrated on June 24th, Artemis's birth day ». More: in popular tradition during the anniversary, dedicated to St. John, "a" ghost hunt "was celebrated which evoked the role of Diana-Artemis as a divine huntress, urging the approach with the phenomenon of the" wild hunt "" ( p.32). In her commendable research work, Chiavarelli also analyzes the beliefs concerning the "breech malformation of the Lady of the Sabbath, often endowed with ursine, donkey or duck legs, beasts connected to demonized aspects of the Great Mother" and connects to this archaic cult the adoration of the walnut tree, sacred to underworld divinities such as Persephone and Artemis / Diana, as well as reports what Barnal claims about the "priestesses of Artemis originally from Karyai, in Laconia" who would be "the walnut fairies" who will decay then in witches (p.57).

For his part, Ginzburg adds to this list the Romanian folk tradition, where "semi-estatic rituals were practiced under the protection of Doamna Zînelor, Also called Irodias o Arada», Assuming the similarity of the beliefs with the fact that Celtic populations had settled for centuries, sometimes as early as the fifth century BC, in Romania (Night story, p.80). Ginzburg also reports that "even at the beginning of the 400th century the peasants of the Palatinate believed that a divinity named Hera, the bearer of abundance, wandered flying during the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany, the period consecrated to the return of the dead", a period during the which, in the Germanic world, "it was thought that the dead wandered around wandering" (pp.81-83) [cf. The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany].

The belief in nocturnal processions was widespread throughout Switzerland: one could only go to them with the soul, leaving the body in the bed, and therefore also living beings, considered particularly fortunate and pious, were admitted (p.81). Ginzburg collects a large literature of cases, between 1400 and 1500, in Alsace, Bavaria, Tyrol and Switzerland, in which groups of individuals, generally women, fall into swoon during the four tempora and claim to arrive in spirit at nocturnal conferences chaired by a female deity (Frau Venus, Frau Selga, Perchta, Holga / Holle, etc). According to the author, these processions are linked to the most ancient myth of the "wild hunt", and therefore also the beliefs of the Friulian benandanti would be framed in the same frame, taking as an example the declaration of a benandante from Latisana, Maria Panzona, tried in 1619, which "she declares that she went several times, in spirit, to the Josefat valley, astride an animal, and that she paid homage by "lowering her head" together with the other benandanti, to "a certain donation felt in majesty above a pozo cariega , called the Abbess"(P.84).

Another striking analogy with the benandanti Ginzburg is found in Swabia, where it is told in the XNUMXth century (in Swabian Annales) of some "wandering clerics"(Note the assonance with" vagabonds ", another name of the benandanti) who knew the past and the future, were able to find lost objects, knew spells that protected people and animals from the action of witches and distanced the hailstorm. Not only that: they also declared that they were capable of evoking "the furious army, made up of children who died before being baptized, men killed in battle and all "ecstatic"That is, from those whose soul had left the body without returning to it. Again, they claim to be able to perform such prodigies by being admitted into the "mysterious kingdom of Venus": this, of course, links them to the female divinity worshiped during these ambiguous nocturnal conferences, the Frau Venus germanica reminiscent of the Mediterranean Aphrodite. It is not surprising, therefore, that the inquisitor Ignazio Lupo stated that "the witches of Bergamo gathered on Thursday of the four tempora on the mountain of Venus, the Tonale, to worship the devil and have their orgies" (pp. 85-88) .

The myth of the "wild hunt" and the god who leads the "raging army"

The myth of the nocturnal procession recalls, as we have said, that of the "wild hunt", widespread throughout central-northern Europe, formed by those who died before their time, such as the warriors who died in battle, forced to wander during the four tempora (and in particular in the nights that go from Christmas to the Epiphany) until the period that they had to spend on earth has elapsed. According to many testimonies, the ranks of the dead, called the "furious army", would be led by the legendary wild man or vegetation demon, known by the name of Harlechinus or Hellequin (The benandanti, p.77). According to Chiavarelli, the myth of Diana's procession and that of the wild hunt ended up merging: now synthesized in the new beliefs, the two phenomena will become inseparable and will both contribute to the tradition of the witchcraft sabbath; the demonic character who leads the feral mesnie it is sometimes confused with Odin who "from an ancient Norse god, has now fallen into the prototype of the devil", others with Arthur, the ruler of the knights of the Round Table in the British epic, still others with the ancient Celtic god Cernunno or Kernunno (Diana, Harlequin, p.26), the "horned god" of the witch religion mentioned by Murray (The god of witches, pp. 21-42) [cf. Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun'].

The characters of Odin and Arthur are both related to the bear (with whose skin, we recall, the priestesses of Artemis Brauronia disguised themselves during their rituals). The animal, in addition to a relationship with Aphrodite, evokes possible references to the North Star (Ursae Minoris) as well as axiality (the sacred ash tree Yggdrasill, the World Tree to which Odin hangs for nine days; the sword that Arthur extracts from the rock). Chiavarelli points out that the bear is also semantically evoked by both the name Arthur (arctos, bear), and from the denomination of the «bands of warriors" bears "of the army of Odin, i berserker, twelve, among other things, like the knights of the Breton sovereign "(Diana, Harlequin, p.29). It should be noted, among other things, that the name of Arthur semantically also recalls Artio, an ancient Celtic goddess of hunting and abundance, often depicted in the guise of a bear. The author goes even further, further investigating the most recent European folklore: "TheOld nick, a demonic entity from northern Europe then canonized as Saint Nicholas, symbol of the Old Year won by the new (the Child of light of the Mysteries, reactivated in the Child Jesus) and the Santa Claus American, analogous to the white-haired Santa Claus who travels on his sleigh pulled by deer, are, surprisingly, the Nordic Odin himself, the "king" of the Wild Hunt! " (p.47) [cfr. The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany].

A mysterious universe thus unfolds, made up of fertility rites, horned deities, deer and the use of hallucinogens (fly agaric), which leads Chiavarelli to investigate the folklore of the Siberian shamanic populations. This search actually allows us to find the semantic roots of Harlechinus or Hellequin, thewild man who often leads the wild hunt in the testimonies collected by the Inquisition. In fact, the author discovers that "among the North Siberian Turks there is a shamanic ceremony in honor of the terrible, great, cruel Ärlik, father of the community and primordial ancestor, to whom horses are sacrificed (Hell equine) ", An infernal divinity similar toErlik of the Altaics and al Yerlik of the yellow Uighurs, who use horns as weapons. Considered the progenitor of humanity, prototype of the first dead like the Indo-Iranian Yama, he is worshiped with the denomination of Erlik Khan as ruler of the world also by the Teleuts, the Buryats and the Turco-Mongols, while among the Tartars it is called Irle-khan. The author informs us that "the invocations to the god, who lives in a palace of black mud in the gloomy depths of the nine degrees of the underworld, precede the sacrifice of a horse" (p.68) [cf. Divinity of the Underworld, the Afterlife and the Mysteries]. Again, it is handed down that Erlik created barley (he is therefore an ancient god of fertility, like the original Latin Saturn, husband of Opi) and it seems that he is offered "variegated fabrics, multicolored pieces that would seem no different from those that form the costume of Harlequin of Bergamo, a character who keeps, in his name, the key to the underground world from which he comes. […] The Harlequin of the Commedia dell'Arte was originally a devil "(p.82). On the other hand, renowned scholars such as Toschi and Meuli share the opinion that Carnival masks embody the souls of ancestors, demons and underground entities that usually show themselves in the twelve days between Christmas and the Epiphany [cf. From Pan to the Devil: the 'demonization' and the removal of ancient European cults].

There is, therefore, a red thread that clearly unites the very ancient shamanic cults of the Siberian populations, the pre-Christian Northern European cults (Cernunno, Odino), and the more recent folklore (San Nicola, Santa Claus, the Krampus) up to even reaching the profane folklore of the medieval masses (Arlecchino but also Pulcinella, whose mask, the "black wolf" alludes to Hades, the underworld god with the wolf's cap that made invisible). In the background, "the traces of other armies of young initiates emerge, covered by animal skins, such as the bersirkir, the furious bear-warriors of the Scandinavian tradition, the Longobard cynocephalus or the ulfhedin, wolfweres of Germanic culture, similar in certain characteristics to the Roman Luperci and to the initiates of Apollo Liceo or Zeus Lycaios "(p.183). Often, in folklore, the battles to which these armies of initiates undergo are also consumed between members of the same group: so it happens, as well as for the benandanti and sorcerers, also for the Călușari of southern Romania, who fight both among themselves and against strigoi, as well as for i kresniki Balkans, i it's delicious Hungarians and the burkudzäutä Ossetians [cfr. Metamorphosis and ritual battles in the myth and folklore of the Eurasian populations]. According to Chiaverelli, "such mythical-ritual scenarios seem to underline the need for fighting between groups of opposing forces, albeit complementary, one of which always personified the negative aspects of antagonism" (p.185-186), aimed at restore the fertility of the fields in the most critical moments of the agricultural year, i.e. indicatively from the beginning of November (feast of the dead) to the Epiphany, an anniversary in which today in popular folklore the Befana is celebrated, which is nothing but yet another mask attributed to the goddess of ancient European agrarian cults.

REFERENCES

- Emanuela Chiaravelli, Diana, Harlequin and the flying spirits. From shamanism to the "wild hunt". (Bulzoni, 2007).

- Giorgio Galli, Mysterious West. Bacchantes, Gnostics, witches: the losers of history and their legacy. (Rizzoli, 1987).

- Marija Gimbutas, The language of the goddess. (Venexia, 2008).

- Charles Ginzburg, The benandanti. Witchcraft and agrarian cults between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. (Einaudi, 1966).

- Charles Ginzburg, Night story. A decipherment of the Sabbath. (Einaudi, 1989).

- Henry Kamen, The Iron Century. 1550-1660. (Laterza, 1977)

- Margaret A. Murray, The god of witches. (Ubaldini, Astrolabe, 1972).

interesting, thanks