In ancient times, among the Celtic populations, at the beginning of August Lughnasadh / Lammas was celebrated, the festival of the first harvest, established according to the myth by the god Lugh himself. An analysis of the functions of the latter will allow us to highlight its remarkable versatility and correspondences with other divinities of the Indo-European traditions (such as Apollo, Belenus and Odin) and even with two divine powers of the Judeo-Christian tradition apparently opposed to each other. : Lucifer and the archangel Michael.

di Marco Maculotti

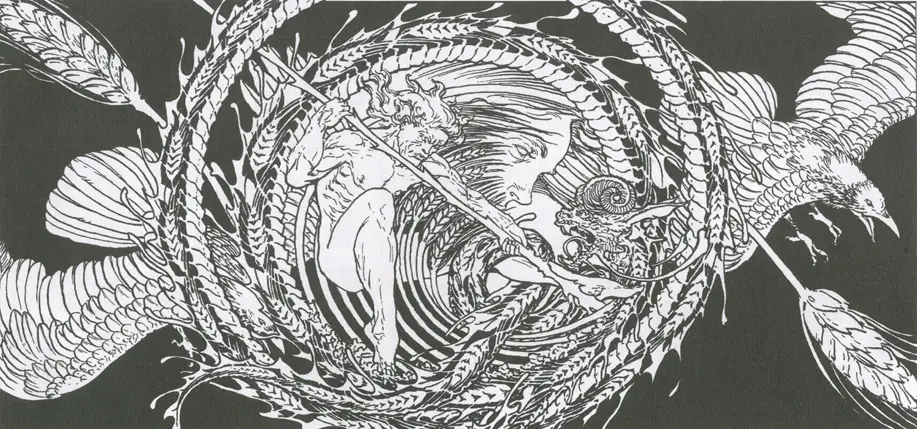

cover: Courtney Davis, "Lugh, the Sun God"

As is well known, consistently with the archaic conception of cyclic time Celtic peoples imagined the year as a wheel, to the point that they had only one term to define these two concepts. The wheel of the year, for the purposes of setting the sacred calendar and identifying the main collective celebrations, was divided taking into account the solstices and equinoxes and particular importance was given to the four intermediate dates: Halloween (November 1), imbol (1 February), Beltane (1 May) e Lamas (August 1). English rural festivals (Wakes, "Vigils") in medieval times took place between March and October, or in the harvest season, depending on the date of the local patron saint. However, previously, in pagan times, they took place almost everywhere in early August, when the time between the cutting of the hay and the harvest was celebrated [Graves 204].

Lughnasadh/Lamas

In Celtic-Gaelic Ireland, the rural celebration of early August was called Lughnasadh, or «Lugh's wedding " or "mass in honor of the god Lugh or Llew". The Anglo-Saxons called it Lamas, from loaf-mass, "Mass of the loaves", with allusion to the harvest and thekilling of the god of wheat [Graves 204]. According to Irish tradition, it was the god Lugh himself who instituted this holiday, which consisted of a large assembly on the plain of Meath, in honor of his adoptive mother. Taultiu (equivalent to the Brigit of the Gauls), telluric deity of fertility [Markele 86]. It seems that Lughnasadh was first of all one royal party: the king presided over horse races and poetic certami ("Games of Tailltinn"), but there were neither warrior fights nor ritual sacrifices [Markele 190]. It was supposed, in fact, that the king, at this time of the year, had reached — just like the Sun he represented on earth — at the height of his power.

In this regard, we note how Guido von List wrote that, in the tradition of the ancient Germans, in the month of August (aust) the so-called divine emanation was venerated Biflindis, translatable as "He who is about to sink", which is transforming itself [List 50] [cfr. Guido von List and the magical-religious tradition of the Ariogermans]. From this moment on, therefore, the Sun would begin to descend more and more in the sky, until it reached its nadir during the so-called "winter crisis" of the Winter Solstice, days during which it seemed to disappear for three days and then born again, or to go up again. This is why his death was celebrated on the feast of the first Sunday in August ("celebration of Lugh", understood as the "Spirit of the Wheat" which muore, or rather that it is cut, only to be reborn the following year).

This recurrence was observed until recently in Ireland with ceremonies similar to those of Good Friday: a kind of day of the dead in which a funeral procession was held, led by a young man who wore a wreath of flowers [Graves 347]. Even in medieval England the festival did not lose these funeral characters: Robert Graves he recalls in this regard the celebrations for the death of William Rufus (a "double" from Lugh), the red-haired hunter killed on a hunting trip in the New Forest who was placed on a hay cart and whose corpse was seen by farmers in the region just as they were intent on mourning the death of the mythical Lugh [Graves 348]. However, we emphasize once again, on the feast of the first harvest no human sacrifices were made, but the rural people limited themselves to mourn the death of the "God of Wheat".

I immolatory sacrifices, on the contrary, they occurred in all Indo-European cultures precisely during the winter holidays, when the heliacal star reached its nadir, and therefore it was believed that the human sacrifice of its earthly representative (the king or his substitute, such as the "Mad King" or "King for a day" of the Latin Saturnalia) to reinvigorate its power. These bloody rites were based on the concept of "ritual sovereignty": the king knew he was the mortal companion of the land goddess- hence the custom of sacrificing the king if his "power" was destined to diminish with age [Powell 122] [cf. Cosmic cycles and time regeneration: immolation rites of the 'King of the Old Year'].

Mircea eliade expresses this concept of "ritual sovereignty" by affirming that "one could become king of Ireland (Eriu) only if one married the homonymous tutelary goddess; in other words, sovereignty was accessed through a Hieros Gameos with the goddess of the Earth (…) This Hieros Gameos guaranteed for a certain period the fertility of the country and the fortune of the kingdom "[Eliade 151-2], adding later that" the king is the representative of the divine Ancestor: the 'power' of the sovereign depends on an unearthly sacred force, which is both the foundation and guarantee of universal order"[Eliade 173]. To put it more clearly, the Celts understood that the life and prosperity of humanity (the king) were possible only if they recognized the divinity of the earth understood both as soil (and, therefore, homeland) and as a stage of forces. in which man can act and reach the path of spirituality and knowledge. For this reason, in the feast of Lughnasadh it was the goddess Taultiu who received the offerings, while Lugh was considered only the founder of this sacred occasion.

Lughnasadh was, as we have seen, the feast of the first harvest, and as such it took place under the protection of the telluric goddess of fertility, Taultiu, Lugh's adoptive mother, who, according to the myth, immolated herself to ensure nourishment and prosperity for her many children. This time of year was marked by the advent of the hottest and driest days of the year, the so-called "dog days", where the canid represented the rise of Sirius, around 23 July. These days, the same sunlight that had provided nourishment and fertility for the rest of the year now threatened the earth with drought. Precisely for this reason they did not sacrifice human victims, but gave thanks to the telluric gods by offering them the fruits of the first harvest to escape the danger of drought and, therefore, unsatisfactory harvests. Il sacrifice of the first harvest ("The killing of Lugh", the "King of Corn") in other words allowed the rest of the harvest season not to suffer the fatal effect of the "days of the dog". This critical period extended, in full, from the last days of July to the September equinox. With these offerings, the Celts used to symbolically emphasize the report symbiotic e mutual between the human consortium and nature.

The god Lugh

Deity of the three functions

However, Lugh was not just a "Grain Spirit", but an incredibly multifaceted deity. In Julius Caesar's interpretation of the deities of the Celtic pantheon in De Bello Gallico, Lugh (Lúg / Lugus) came assimilated to Mercury and indicated as the most revered god of all. One of Lugh's best known epithets is Samildanach, "Lord of all arts" or knowledge in general [Powell 121]. However, the equation proposed by Caesar is not the most precise: Lugh, in fact, unlike the Roman Mercury, is not only a god of the intellect (nor is there any mention of his protection of traders and thieves), but it covers all three functions of the Indo-European cultures theorized by Dumézil.

Indeed, he it belongs at the same time to the priestly class insofar as harp player, poet and doctor (like Apollo); to that warrior as fighter and hero (like Hercules); and, finally, to the productive one as carpenter, blacksmith and craftsman (like Loki in mythology Norse, possibly connected to Lugh also etymologically). One of the happiest comparative equations could be that with the titanic Prometheus of the Hellenic tradition. Because of this triple function, Lugh was often represented in iconography as a god with three faces, similarly to the Hindu trimurti [cf. The primordial and triple god: esoteric and iconographic correspondences in ancient traditions]. If it must be recognized that Lugh is neither the primordial god, nor the god of origins, nor the king of the gods, he is nevertheless above all others, and "alone embodies in himself the set of divine functions that , from the point of view of Druidism, they are also, fundamentally, the functions that humanity must fulfill to achieve the unity of the world above and the world below, a unity without which Chaos (that is, the Fomors of mythology, Nda) dominates "[Markele 89].

50% Tuatha dé Danann and 50% Fomori

At the same time being part of the Tuatha de Danann like gods Fomors, Lugh participates in a double nature, and this places him above and beyond any dualistic classification. Of the Tuatha Dé Danann, he possesses the "organizing power, socialized and spiritualized to the extreme", but adds to it the brute and instinctive force of the Fomori, chaotic forces of Celtic-Irish mythology. In other words, Lugh looks like a real one synthesis of two opposing forces who oppose and fight: the very embodiment of a monistic principle, deriving from typically Celtic refusal to interpret duality as absolute [Markele 82].

This makes Lugh appear as a numinous power beyond all categories and functions, as he summarizes them all in himself: for this reason, he was called the "Multiform craftsman", and as such repository of the secrets of the gods [Markele 87], thus also recalling the Mediterranean Volcano / Hephaestus and the Norse Loki, divinity of the inner fire and of the transformation of matter into something higher, etheric and spiritual. In the same way Lugh, although born from the Fomori, also summarizes in himself all the opposite characters typical of the Tuatha, opponents of the former. He is at the same time the ambiguous one trickster and the "Bearer of Light", similarly to the Lucifer of the Judeo-Christian tradition, as we will see below. Lugh, as belonging to the two divine categories of the Celtic pantheon, “allows the world to find its balance, privileging the organized forces (the Tuathas) and governing the instinctive forces (the giants Fomori) [Markele 84].

Lugh and the sacred city of Lyon

Lugh must have actually enjoyed a very important cult, as well as in the Anglo-Saxon-Irish area, also in French Gaul, another territory formerly inhabited by Celtic populations: from its name, the name of the city of Lyon derives (originally Juldunum, the "fortress of Lug"), which on the other hand was considered a sacred city by the Gauls. In Lyon, the Gauls celebrated the four most important holidays in the calendar, which fell forty days after each solstice or equinox. We also note that, when the Romans had conquered and organized Gaul according to their own political-economic purposes, they made Lyon the intellectual, political and religious capital of the Cisalpine province [Markele 86]. In addition to Lyon, the god also gave its name to other important cities, such as Laon, Leiden and Carlisle (Caer Lugubalion) [Graves 347].

Lugh and Apollo

According to a legend related by the pseudo-Plutarch, the foundation of Lyon was determined by an omen: the place was designated by a flock of crows [Markele 85]. And here it should be noted that the crow was the sacred animal to Lugh (as well as to Apollo and to the Nordic Odin). This may seem paradoxical, given the purely luminous nature of the god: but, returning once again to what was previously said about the duplicity of Lugh, it can be seen that his name was undoubtedly in relation to a root which means "light" (or "enlightenment", also in a mental / intellectual sense, and this evidently links him to the Roman Mercury, god of intelligence and intuition) and "Whiteness" (Greek leukos, "white"; Latin luxury, "light"). For completeness of information, we report the authoritative opinion of Graves, according to which the name of the god was also related to lucus, "woods", and could even derive from Sumerian lug, "Son" [Graves 347]; moreover, De Vries adds that, in the ancient Gaelic language, alkaline meant "crow".

Returning to what was previously said about the duplicity of Lugh as a luminous god and at the same time connected to the raven, we recall how, on the other hand, also theApollo Lyceus was simultaneously connected to an idea of luminosity and purity (Apollo hyperborean, solar and polar god) and to a more ambiguous one, since the above epithet was derived not only from the concept of luminosity and splendor, but also from the Lupo, an animal that in the European tradition is often a harbinger of danger or adversity. We can therefore conclude that, in all probability, Julius Caesar was not precise in associating Lugh with Mercury, as his dualistic characteristics make him much more similar to Apollo Lyceus Mediterranean, which, for its part, often presented ambiguous and not very reassuring characteristics [cf. Detienne, Apollo with the knife in his hand].

Lugh and Lucifer

From the same Indo-European root luxury also derives the divine figure of Lucifer /Phosphoros, "Light carrier": a god who presents, on the other hand, notable similarities with both Lugh and Apollo, and even with the aforementioned Prometheus, who for having brought the "fire" (or the "light of gnosis") humanity was condemned to a terrible torture by the gods of Olympus. Likewise, again because of his arrogance, in the Judeo-Christian tradition Lucifer was thrown down from heaven by the supreme god Jehovah, and condemned to live hidden in the depths of the earth (similarly also to the Mediterranean Saturn / Kronos, ruler of the Age of 'Gold) [cf. Apollo / Kronos in exile: Ogygia, the Dragon, the "fall"].

If this were not enough to demonstrate the validity of the Lugh / Lucifer association, it should be added that, according to tradition, Lucifer was precipitated to Earth on August 1st, the day of Lammas! And here we return with our thoughts to what von List wrote about the god revered in the month of August: «he who is about to sink» ... or to fall. Again: although the myth is less known, it is said that Apollo was also thrown to earth by Zeus, following his revolt against the Cyclops, militia of the Olympic god, guilty of killing his son Asclepius, god of medicine and son of Apollo . For this act of hybris, Apollo was in fact condemned by the father of the gods to spend a "great year" on Earth, to graze the flocks of humanity, that is to say to take care of man and his spiritual evolution for the duration of an entire eon [Detienne 258].

Lugh and Beleno

There is no doubt that Lugh overlapped the Proto-Celtic god in the Archaic period Beleno (or Belanu), divinity of light (from Proto-Indo-European *nice-, "Light"), one of the greatest and most influential among the ancient European gods, for whom sacrifices and rites connected to the solstices and therefore to the solar cycles of the year were performed, whose companion was the goddess of fire Belisama, to which the sacred altar had been erected in ancient times on which the Duomo of Milan was later built. This divine pair of light and fire was mainly worshiped by the Ligurians and give it Iberians, and then give Celts continental (Italy, France) and insular (Great Britain). The very ancient root nice, present in many protolanguages, according to some sources it would have the transcendental meaning of "appearing from the other world" and of "illumination from the world of the Gods", and it seems to be also connected to the primordial god of light Baal, revered by the Sumerians in the sixth millennium BC

Returning to Beleno, we find in the context of his functions all those that, later on, were associated with Lugh: he, in fact, was known for his influence on sunlight and consequently on agriculture, temperature and healing; also, like Lugh in his appearance mercurial, he oversaw the enlightenment of the psyche in the spiritual and mental sense as a guide to innovations and inventions. Beleno also seems etymologically connected to the ritual feast of Beltane (the holiday that precedes Lammas in the context of the four main celebrations of the Celtic calendar), celebrated in early May, to commemorate the rebirth of the god of light, during which the druids performed apotropaic rituals with bonfires and fires.

Lugh and Odin

Furthermore, as De Vries first noted, Lugh also has several characteristics that allow him to be partially identified with the Odino / Wotan of the Germanic-Norse tradition. On the other hand, it is no coincidence that, on the same date in which the Celts celebrated the "harvest moon", that is the feast of Lugh and his mother Taultiu, the Norsemen celebrated the sacred marriage between Odin and Frigg [Guidi Guerrera 24] or between the numinous forces of heaven and those of earth. Like Odin, Lugh is at the head of the divine militias in the fight against the giants; like him, he is owner of a wonderful spearae portentous; as the father of the Norse gods, he faces war not with force alone, but mainly with magic, similarly to the Hindu Varuna. In addition, like the Norse god, the crow is sacred to him, he is a poet and musician.

Finally, if Wotan is one-eyed, Lugh is the grandson of a “one-eyed one-eyed” [Markele 88] and, in order to work his magic in battle, during the fight he turns a blind eye. In this regard, Eliade writes: "The Irish texts present Lug as a military leader, who avails himself of magical powers on the battlefield, But also as great poet and mythical ancestor of an important tribe. These traits bring him closer to Wotan-Odin, who was also assimilated to Mercury by Tacitus. It can be concluded that Lug represents sovereignty in his magical and military aspect of him: he is violent and fearsome, but in addition to warriors he also protects bards and "sorcerers". Just like Odin-Wotan, he is characterized by his magical-spiritual abilities, and this explains why he was homologated to Mercury-Hermes "[Eliade 146-7] [cf. Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun'].

Lugh and the archangel Michael

It is also interesting to note how some characteristics of Lugh later resulted, in the Christian era, in the iconography of the archangel Michael, leader of the celestial militias. Note, first of all, how the sword (or alternatively the spear, typical of Apollo) were attributed typical, well before that of St. Michael, of the Celtic god in question. Furthermore, the days consecrated to the archangel were 8 May and 29 September, the same as the rising of the Pleiades, against the backdrop of the Milky Way, which in Celtic countries was called the "castle of Lugh". Again: in the basilica of San Michele Maggiore in Pavia, the archangel was venerated in the dual function of accompanying the deceased and of keeper and giver of royalty, in whose role he presided over the coronation of Lombard kings — exactly the dual functional scope of the Celtic Lug.

This is not surprising, considering that the Germanic populations to which the Lombards belonged were for a long time under the influence of Celtic culture and reported numerous contaminations [Calabrese]. In addition, among the recurring epithets of Lugh, we find some that could easily refer to the archangel: Lonnbeimenech ("He who strikes furiously"), lampfada ("Long-handed") e Grianainech, a term that in Irish conveys an idea of warmth and brightness and is also referred to the heliacal star [Markele 87], of which St. Michael in question is the personification. In this sense, we find a continuity between the pagan worship of Lugh and the Christian one of the archangel Michael, which, on the other hand, is particularly felt in France.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- M. Detienne, Apollo with the knife in his hand (Adelphi, Milan, 2002).

- R. Graves, The White Goddess (Adelphi, Milan, 1992).

- G. Guidi Guerrera, Seasons of Magic (Hermes, Rome, 1996).

- M. Eliade, History of religious beliefs and ideas, vol. II (Sansoni, Florence, 1980).

- G. von List, The religion of the Ariogermans and Urgrund (Settimo Sigillo, Rome, 2008).

- J.Markale, Druidism. Religion and divinity of the Celts (Mediterranee, Rome, 1991).

- TGE Powell, The Celts (Il Saggiatore, Milan, 1959).

extremely illuminating