Behind the Christian mask of Candlemas and Santa Brigida, the beginning of February brings us back to the ancient pre-Christian festivities concerning the Triple Goddess and the expectation of the imminent rebirth of nature.

di Marco Maculotti

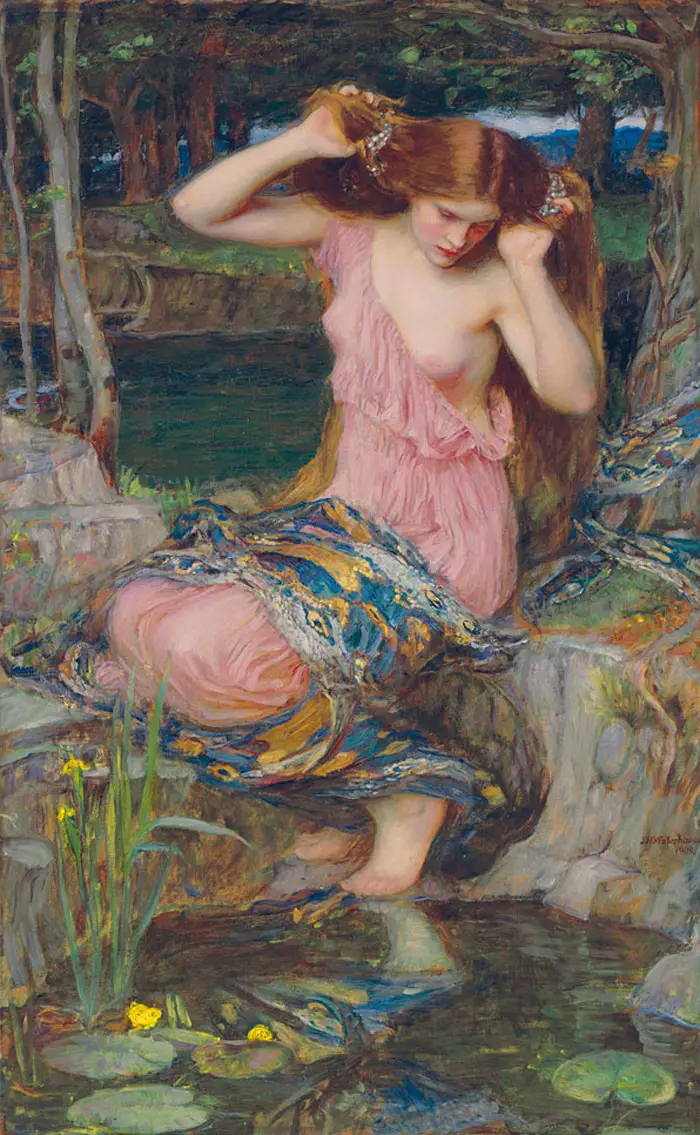

cover: Laura Ramie, "Brigit"

The feast of imbol, which in the Celtic calendar was equidistant from Halloween and Beltane, marked the beginning of spring and had, as we will see in the continuation of this article, notable correspondences with the Roman one of the Lupercalia, also celebrated in the month of February [1].

It is generally made to derive imbol from the Irish "in the womb", with reference to the pregnancy of the sheep, to indicate that originally it was a feast linked to the suckling sheep: in this period, in fact, the lambs were born and the sheep produced milk. On the other hand, that of the sheep is a traditionally spring "epiphany", as the beautiful season is born under the sign of the ram, a fertile and virile animal, whose characteristics evoke the energetic awakening of sleeping nature in winter. Christophe Levalois writes [2]:

“The sign of Aries begins on March 21st, that is to say at the equinox. The wolf, a typically winter animal, precedes it. This period sees the transformation of the wolf into a ram. Nature becomes prolific, from barren and cold as it was. It is always stimulated by the same force which, however, presents itself under another aspect. "

If we will return to the wolf later in this study, it must be emphasized here as in Jean Markele's opinion [3] the term bowl also has the meaning of "sack", with reference to a mythical container used to symbolically contain the food supplies for the whole year. Or again, it could convey the idea of a "swelling" and "blow" which causes it. According to the latter interpretation, imbol would then be the feast of the "Vital Breath", and the swelling ovine udders would be the visible manifestation of the renewing action of this blow.

The feast of imbol it was characterized by banquets and purification rites. We have already mentioned the functional correspondence with the Roman Lupercalia, celebrated on February 15, which also took the form of purifying rites in view of the advent of spring. On the other hand, the entire month of February in the Celtic calendar was dedicated to purifications and exorcisms, a custom to be considered in relation to the mythical complex of the "winter crisis": waiting for spring, the border that separates the world of the living from that of the dead is still unstable, not yet "well defined". Hence, the need to take the necessary ritual measures to ensure that the spirits of the ancestors do not negatively affect the harvest of the coming year. [4].

According to the authoritative opinion of the French historian of religions George Dumézil, in this key period of the agricultural calendar [5]:

“A necessary and disturbing link was also established between two other worlds, that of the living and that of the dead […] those days ritually called into question the very schemes of social and cosmic organization. "

The triple goddess Brigit

Nonetheless, the ritual-calendar complex of imbol it was not limited to February 2, but extended to the days immediately preceding and following. In fact, on February 1st, the feast of Brigit (or Brigid), the triple-faced goddess who was later "Christianized" in S. Brigida (which is still celebrated on that date today). The abbey of Kildare where the saint, the second patroness of Ireland, would have exercised her spiritual functions during her natural life was built on a previous Celtic sanctuary consecrated to the goddess Brigit, where a female fire cult not unlike that of the Vestals was exercised Roman [6].

Brigit combined cultural functions [7] and warlike of Athena / Minerva with those guarantors of fertility and abundance: in this way, as a Triple Goddess, she covered all three functions found in all traditional Indo-European cultures by Dumézil. Brigit was considered auspicious as both giver of poetic inspiration and healing power (first function), or as helper on the battlefield, similarly to the Germanic-Old Norse Valkyrie (second function), and finally as guarantor of the prosperity of the fields and the economic well-being of the community (third function).

From this, it is reasonable to suppose the existence of an archaic cult, probably in relation to what Mircea Eliade called "Neolithic background", characterized by a religious and social system oriented in a different way than that of the historical Celts, from Julius Caesar onwards; a cultic system in which the totality of religious-social functions belonged to a Great Mother.

Brigit had as epithets Belisama ("She who shines a lot") [8], sulis (the goddess of springs), quarrel ("The highest, the sum") e bricta ("brilliant"). The Romans venerated it, as well as as an epigone of Minerva, in connection with the goddess Vittoria and — unique case —, was the only Celtic goddess to be absorbed in pantheon Roman with the epithet of epona, protector of horses. Due to its versatility and its peculiarity of brilliance and prominence, Brigit / Belisama can rightfully be considered the female equivalent of Lugh / Belenos, which perhaps replaced it with the advent of the metal age, according to the interpretative scheme of Bachofen, Gimbutas and others [9].

Even the "Christianized" version of the celebration, Candlemas, it was maintained as a festival of Light as well as of Purification. Pope Innocent testified that Roman women celebrated the festival of lights on that day, "whose origin is taken from the tales of poetsAnd all night they watched and sang praises holding lighted candles.

Naturally, with the spread of Christianity, Brigit's functions are absorbed by the Virgin Mary (being she too virgin and mother), and the correspondence is sometimes clear-cut - as in medieval Irish poetry, where the goddess is referred to as "the Mary of the Gaels" [10]. Yet, continues Robert Graves in his gargantuan study The White Goddess:

«[…] In some parts of Britain Saint Bridget maintained her characterization of Muse until the Puritan revolution, exercising her therapeutic powers largely through poetic spells near sacred wells. " [11]

There is also to underline what the Caption Aurea by Jacopo da Varagine [12] refers to Candlemas, that is, that the Church wanted to sanctify the ancient pagan festival of Persephone, during which "the Romans offered sacrifices to February, or rather to Pluto and the other infernal gods ». It will therefore be noted that even in the Roman calendar February was considered at the same time the period used for the Purification and — just saying — the "month of the dead", since its etymology derives from february, "He who purifies", which is as we have seen an epithet of Hades / Pluto, lord of the dead and the underworld [13] and February, goddess of purification of Sabine origin assimilated to Juno.

It is superfluous to recall here the myth of the kidnapping of Persephone / Proserpina by the god of the underworld: we limit ourselves to underlining the inevitable functional correspondence between this young Mediterranean goddess who, destined to remain for four months (the winter season) in Hades with her husband, returns to the world of the living with the advent of spring, and the Celtic Brigit celebrated a imbol, a festival which, as mentioned, marked the beginning of the season of fruits and flowers in the Celtic "wheel of the year". When Brigit returns to her country, the grass turns green, the flowers bloom and the cow's udders are filled with milk.. Another female deity very similar to Brigit, perhaps even a hypostasis of her, canonized in St. Agatha, she is the patroness of nannies and protects young mothers in childbirth: her feast is on February 5, therefore also in the "mythical time" used for purification and connected to the return of Light to the world [14].

As during the Nordic festival dedicated to Lussi (later S. Lucia [15]), even during Brigit's feast, candles are lit and particular sweets are cooked, round-shaped crepes connected to the symbolism of abundance, but also to that of the aforementioned "swelling", by virtue of the leavening process.

S. Biagio, the "breath" and the wolf

From this we return to the idea of "blow", and it cannot come as a surprise for us to note that on February 3, just after the feast of the goddess Brigit e imbol, a feast was celebrated which was then canonized on the feast of St. Blaise, whose name probably derives from the Germanic biasen, "Wind", and therefore with reference both to the (last) cold winter wind, and to the "breath of the spirit", connected to "divine inspiration" [16]. And if we have already noted that Brigit was considered the giver of poetic inspiration, we could perhaps go further by relating Blaise to an ancient Germanic-Norse god whose name also bears suspicious similarities to that of Brigit.

We are talking about Bragi, deity of poetry considered by some to be a hypostasis of Odin / Wotan in his capacity as possessor of poetic inspiration. On the other hand, Wotan among other things is also considered, from the etymology, the god of the "rushing wind" (hence his role as conductor of the "Wild Army" [17]), as well as of courseinspiration divine (proto-Germanic *wođaz, identical to Latin vātēs, "Seer"). The idea of splendor is also implicit in the name of Bragi — braga it is used in connection with the shining of the Northern Lights [18] -, and this also makes him a sort of male parhedron of the goddess Brigit.

It should also be added that, if we do not want to refer to a Germanic etymology, we could consider the feast of St. Blaise deriving from the French transcription of the Breton bleiz (Welsh bleidd), what does it mean "Lupo". In all versions of the Merlin legend (which, like Odin / Wotan, is a Saturnian-winter "epiphany"), the wolf is his faithful companion; only in the most "Christianized" stories does the animal disappear, to be replaced by a hermit named Biagio [19].

The wolf is also found, as we have seen, in the Roman Lupercalia, a festival during which the members of a specific brotherhood, the Luperci, dressed in wolf skins and made a purifying run around the Palatine, to ward off evil winter spirits and therefore favor the abundance of flocks and fields for the year to come. The expulsion (also in February) of Mamurio Veturio, the "horned god of the year", was also linked to this ritual-calendar complex. doppio of Mars and demon of vegetation, whose symbolic immolation would have ensured the return of spring [20].

However, the wolf is not exempt from connections with this complex ritual consisting of purification rites, waiting for spring and "expulsion" of the spirits of the dead and of the infernal / winter gods. According to a belief that emerges from time to time in the trials on witchcraft over the centuries, the mythical figure of the werewolf, present in almost all European folklore traditions, is in fact to be considered in relation to the so-called "ritual fights" carried out in spirit from these against demons and sorcerers. According to the famous "werewolf of Livonia", of which Ginzburg reported the trial testimonies, werewolves would be considered as tools and helpers of God ("dogs of God") and the stakes of the ecstatic battles fought against demons and sorcerers, similar to the Friulian tradition of the benandanti, would have been the fertility of the fields [21]:

"Gthe sorcerers steal the sprouts of wheat, and if they cannot be plucked from them, famine ensues. »

In these folkloric beliefs that are found up to the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries we can identify the residues of a very ancient shamanic tradition, which in all probability already in an intermediate phase had, so to speak, hidden itself in its esoteric form to instead develop an exoteric one ( farces of male brotherhoods on the example of the Lupercalia, masquerades of the Krampus et similia).

The bear and the spring incubation

In addition to the wolf, another animal enjoyed a certain importance in this period of the agrarian-ritual calendar of ancient Europe: the bear, which, awakening from winter hibernation and coming out of its den, officially sanctioned the beginning of spring ... or the delayed by 40 days. In his studio The Carnival, Claude Gaignebet recalls a famous popular saying spread throughout the area of Celtic influence [22]:

«When Candlemas comes from winter semo pierces; but if it rains or the wind blows from the winter we are inside. "

This proverb is linked to a belief, widespread throughout Europe, according to which on February 2 the bear (or, depending on the version, any other hibernating animal, as well as the Wild Man [23]) comes out of his lair to ascertain the weather conditions. If the sky is clear, the bear returns to its winter refuge: it is a sign that the winter will last another 40 days [24]. If it is superfluous to underline the symbolic-esoteric value of the number 40 in all sacred traditions (think of the 40 days Jesus spent in the desert, or the 40 days and 40 nights of the universal flood), we underline the fact that even today, with the custom of quarantine, the value of this well-defined period of time as a incubation period, and this is perfectly logical considering that the tale of the bear falls just to imbol.

In other words, February 2 ends winter and virtually spring begins: and yet, the fruits of the new season, albeit already virtually formed, still remain underground, under the winter / infernal snows, in incubation like the bear and the other hibernating animals waiting for the definitive explosion of spring. As Markale points out [25], «The forty days of the bear mean quite simply that if the sky is still clear, that is winter, empty of everything, the purification carried out by the winter is not complete: hence the need for a new quarantine». And from this, we add, the need for one ritual purification community members, which happened to happen just below imbol.

This calendar-ritual period in the Christian calendar was moved forward by one month with the institution of the Lent (from Lat. quadragesima dies, "Fortieth day"), a period of purification that anticipates another rebirth, that of Christ who died on the cross [26]. Yet, still in the Middle Ages, when Christianity had not spread that much in rural areas, the pivot of the popular calendar system, since it sanctioned the transition from the cold to the temperate season, was [27]:

«[…] February 2, the earliest possible date of Carnival, the day on which the bear or the Wild Man came out of his cave to verify the beginning of spring. "

Note that the interchangeability between the Wild Man and the bear denotes the 'median' and 'hybrid' character that this animal has always held in shamanic cultures; This is a tradition that unites Eskimos, Native Americans, Celtic-Norse-Germanic ethnic stocks, Lapps and North Asian populations and which is supported, among other things, by the erect posture of the bear and the almost human use of its appendages [28].

To conclude, we can also identify a connection between the bear and a matriarchal type of cult system in the figure of Celtic goddess Artio, dispenser of abundance, shared by many, from the etymological profile, to Artemis in her role as "Lady of the Animals" (potnia theron). On the other hand also Artemide was called Trivia (Selene in heaven, Artemis on earth and Hecate in the underworld) and also in Braurone there was a sanctuary of Artemis where Athenian girls aged between five and ten were sent to serve the goddess for the duration one year, the period during which they were called arktoi ("Little bears").

"In the guise of bears, Artio and Artemis presented themselves [...] at the border between culture and nature, between disciplined space and the forest, between the human and the bestial, between life and death, and they also lent themselves for this to protect pregnant women " [29] - another feature that brings them closer to Brigit / S. Agate celebrated during the days of imbol. In fact, even Diana / Artemide, virgin and mother like Brigit, she was considered a goddess of childbirth: as proof of this, in Greece the name Artemidoro, "gift of Artemis", was frequent.

Note:

[1] See Modena Altieri, Lupercalia: the cathartic celebrations of Februa and Maculotti, Metamorphosis and ritual battles in the myth and folklore of the Eurasian populations.

[2] Christophe Levalois, The symbolism of the wolf. Arktos, Turin, 1989, p. 36.

[3] Jean Markale, Celtic Christianity and its popular survivals. Arkeios, Rome, 2014, p. 179.

[4] On the "solstitial crisis", cf. Maculotti, Cosmic cycles and time regeneration: immolation rites of the 'King of the Old Year', The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany, Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun', From Pan to the Devil: the 'demonization' and the removal of ancient European cults.

[5] Georges Dumezil, Ancient Roman religion. Rizzoli, Milan, 1977, p. 306.

[6] Jean Markale, Wonders and secrets of the Middle Ages. Arkeios, Rome, 2013, p. 140.

[7] Il Glossary of Cormac says: "Brigit, daughter of the Dagda, the poetess, that is the goddess venerated by poets because of the great and illustrious protection she grants them" (Robert Graves, The White Goddess. Adelphi, Milan, 2011).

[8] So it was called in the area of northern Italy, and especially in Mediolanum. Lthe current Milan Cathedral is built over the ancient temple of Belisama; hence, the characteristic of the cathedral, still in force today, of exhibiting at the highest point a statue of the Madonna rather than one of Christ, a unique case in all of Europe. Robert Graves connects it to the belili "" White goddess of the Sumerians ", older than Ištar and goddess not only of the moon but also of trees, as well as goddess of love and the afterlife [...] But above all, Belili was a goddess of the willow and a goddess of wells and springs" (Graves, op. Cit., P. 67). This actually connects her to another Brigit epithet, sulis.

[9] On Lugh, cf. Maculotti, The festival of Lughnasadh / Lammas and the Celtic god Lugh. For Bachofen's theory, cf. JJ Bachofen, Mothers and Olympic virility. Secret history of the ancient Mediterranean world. Edited by J. Evola. Mediterranee, Rome, 2010.

[10] Graves, op. cit., p. 452.

[11] Cit. from Wikipedia, entry "Bridget of Ireland": "Analyzing the cult linked to the so-called Fountain of Santa Brigida (St. Brigid's Well) to Liscannor (Lios Ceannuir) in County Clare, Sharkey writes verbatim in his book The Celtic mysteries, the ancient religion: “Many fountains and springs have been sacred since time immemorial. Despite the transformations of objects of devotion and rites, the act of invoking the source of life has never been forgotten. This fountain was once sacred to the mother goddess Bridget who healed with the power of fire and water. In Christianity the goddess was transformed into Saint Brigid, patroness of the hearth, of the house and of the sacred fountains ”. This fountain, which is a typical example of Irish sacred wells whose tradition dates back to Celtic cults, is the destination of a pilgrimage on the last Sunday of July "[or - we add - just before Lughnasadh, celebration of Lugh, god of Light and, therefore, paredro of Brigid / Belisama]. "In support of his anthropological reinterpretation of the figure of the saint, Sharkey recalls some episodes taken from Irish folk legends, according to which it is said that she was burned at dawn on 1 February during the feast of imbol, an episode that recalls an ancient Celtic ritual. Thus the new Bridget becomes the patron saint of the hearth, the house, the fountains and the healings ». In this light, Brigit appears perhaps in functional connection with the Giöbia or Giubiana which in Northern Italy is still burned in a bonfire in the last week of January; in this regard cf. Maculotti, The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany.

[12] Markal, op. cit. Christianity, P. 180.

[13] On the 'positive' value of the gods of the dead and the underworld, cf. Maculotti, Divinity of the Underworld, the Afterlife and the Mysteries.

[14] We also add that on February 15, in the Roman calendar, Juno, goddess of parts, was also celebrated, and therefore in this sense homologous to Brigit / S. Agate.

[15] See Maculotti, Lussi, the "Luminosa": the double pagan and "obscure" of Saint Lucia.

[16] Markal, op. cit. Christianity, p. 181.

[17] Of Wotan as conductor of the "Wild Army" and of other variations of the mythologem we have already spoken elsewhere; cf. Maculotti, The Friulian benandanti and the ancient European fertility cults and Mollar, The "Ghost Riders", the "Chasse-Galerie" and the myth of the Wild Hunt.

[18] Mario Polia, "Furor". War poetry and prophecy. The Circle - Il Corallo, Padua, 1983, p. 38.

[19] Markal, op. cit. Prodigi, P. 83.

[20] Dumezil, op. cit., p. 196.

[21] Charles Ginzburg, Night story. A decipherment of the Sabbath. Einaudi, Turin, 1989, p. 130. On the subject, cf. Maculotti, Metamorphosis and ritual battles in the myth and folklore of the Eurasian populations.

[22] Claude Gaignebet, The Carnival. Payot, Paris, 1974, p. 17.

[23] Massimo Centini, The wild man. Oscar Mondadori, 1992, p. 93.

[24] This popular belief is, although in the peculiar ways of our age, still alive today. In the famous film by Harold Ramis Groundhog Day (tit. it .: I start all over again) from 1993, Phil Connors (played by Bill Murray) plays the role of a television meteorologist who has to travel to the small town of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, to make a report on the traditional "Groundhog Day", a holiday celebrated in the United States and in Canada on February 2, to coincide with imbol/Candlemas. Again, it is believed that the output of the marmot (Marmota monax) from its den is connected to the arrival of spring (or its delay of 40 days): tradition has it that if the marmot emerges and cannot see its shadow because the weather is cloudy, winter will end soon; on the other hand, if he sees his shadow because it's a beautiful day, he'll get scared and run back to his lair, and the winter will continue for another six weeks. This tradition is made to derive from a Scottish rhyme that reads: "If Candlemas Day is bright and clear, there'll be two winters in the year"(" If the sky is clear at Candlemas, there will be two winters in the year ").

[25] Markale, op cit. Christianity, P. 178.

[26] On Lent, cf. Carnival and Lent: traditional meanings and legacies.

[27] Jean-Claude Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West. Laterza, Bari, 1988, p. 35.

[28] "The idea of permeable borders between the human body and the bear is undoubtedly very archaic, certainly Paleolithic", in fact "its diffusion throughout the northern hemisphere, from Europe to North America, would not be explained otherwise" as a privileged character in the mythical tradition, as the initiator of humanity to the shamanic mysteries [Paolo Galloni, Hunting the bear in medieval forests (i.e., the uncertain boundaries between human and non-human) in Acts and Memoirs of the Pistoian Society of Homeland History].

[29] Germana Gandino, The bear in Celtic and Germanic traditions. In Italian Historical Review, year CXXVI - issue 111, Italian Scientific Editions, December 2014, p. 726.

Bibliography:

- JJ Bachofen, Mothers and Olympic virility. Secret history of the ancient Mediterranean world. Edited by J. Evola. Mediterranee, Rome, 2010.

- Alfredo Cattabiani, Lunario. Twelve months of myths, festivals, legends and popular traditions of Italy. Mondadori, Milan, 2002.

- Massimo Centini, The wild man. Mondadori, Milan, 1992.

- Georges Dumezil, Ancient Roman religion. Rizzoli, Milan, 1977.

- Claude Gaignebet, The Carnival. Payot, Paris, 1974.

- Paolo Galloni, Hunting the bear in medieval forests (i.e., the uncertain boundaries between human and non-human) in Acts and Memoirs of the Pistoian Society of Homeland History.

- Germana Gandino, The bear in Celtic and Germanic traditions. In Italian Historical Review, year CXXVI - issue 111. Italian Scientific Editions, December 2014.

- Charles Ginzburg, Night story. A decipherment of the Sabbath. Einaudi, Turin, 1989.

- Robert Graves, The White Goddess. Adelphi, Milan, 2011.

- Christophe Levalois, The symbolism of the wolf. Arktos, Turin, 1989.

- Jean Markale, Celtic Christianity and its popular survivals. Arkeios, Rome, 2014.

- Jean Markale, Wonders and secrets of the Middle Ages. Arkeios, Rome, 2013

- Mario Polia, "Furor". War poetry and prophecy. The Circle - Il Corallo, Padua, 1983.

- Alwyn and Brinley Rees, The Celtic heritage. Ancient traditions of Ireland and Wales. Mediterranee, Rome, 2000.

- Pierre Saintyves, The holy successors of the gods. The pagan origin of the cult of the saints. Arkeios, Rome, 2016.

- Jean-Claude Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West. Laterza, Bari, 1988.

As always optime

Thanks Francesco