Second and last part of the overview dedicated to the "mirabilia" in the medieval West, to the mythology of"Army of the dead" and the "Wild Hunt"

di Judith Failli

(second part of 2)

cover: Édouard Ravel de Malval, "Death on a Pale Horse ", circa 1865

[follows from The Marvelous in the Middle Ages: the "mirabilia" and the apparitions of the "exercitus mortuorum" ]

Walter Map, Welsh cleric at the court of Henry II Plantagenet, in De nugis curialium (1182-1193), collects numerous stories and wonder, in a work whose inspiration would be found in a reflection on the vicissitudes of the court, compared to the uncertainties of the time [1]. The king's court is "without being time, like time: different, changeable, deceptive, to the point that anyone who leaves it for a moment, on his return, recognizes no one and is considered a stranger" [2]. In this work the author compare the gang of Hellequin, called here Herlethingi family, to the Plantagenet court, also proposing to trace a real myth of origin, having foundations in the Celtic origins of Great Britain.

In the text of Map the name of the torma is in fact derived from that of Herla, the king of the Bretons, who had made an "eternal pact" with the "king of the Pygmies", an ambivalent supernatural character characteristic of folklore; Map also relates and assimilates the court of Herla to the court of the Plantagenets; in fact this fantastic torma would no longer be seen following the coronation of Henry II Plantagenet (1154), as if this royal court had replaced the fantastic army of the king of the legend.

J.-C. Schmitt observes how the narrative develops starting from Herla's acceptance of the pact proposed by the king of the Pygmies: initially it would seem to be a pact between equals, as both enjoy the same social position and the pact could be posed as a strengthening of the pre-existing bonds between the two. In fact, a degree of kinship exists between Herla and the king of the Pygmies which would confer supernatural origins even to the king of the Bretons. Except that [3]:

"[...] the elements of the pact immediately contradict the equality of the parties [...] since the dwarf is a supernatural character, who comes from a world other than that of men, binds Herla to his power and drags him to ruin [...] and covers him with gifts that characterize him as a hunter, conductor of the wild Hunt. "

The unequal relationship between Herla and the king of the Pygmies allows us to understand the danger and the impossibility of a contact and an exchange between the living and the afterlife. In the "false" offering of gifts made by the king of the dwarves to Herla there are "horses, dogs, falcons and all that is necessary for hunting on horseback and with the hawk" and a bulldog (in the original Latin canissanguiris translatable into English bloodhound, to express, intentionally, the ferocity of the animal). The king of the dwarves, before dismissing Herla and her entourage, forbids them to dismount before the bulldog brought as a gift. When Herla returns to earth he discovers from a shepherd that two centuries have passed since his departure and that the town is now occupied by the Saxons; Herla and his parents will be forced to wander forever because the dog will never go down, condemning them to the aerial ride.

The narrative of Map, in addition to being situated in the framework of the 470-type story [4], approaches the motif of Hellequin's gang and the origin of its existence, al semantic field of the "diabolical pact" without, however, ever naming it as such, thus not proceeding towards a Christian re-elaboration of the theme but remaining in the field of the wonderful folkloric [5]: Herla is here punished for having considered possible the exchange with the king of the dwarves, and therefore having believed possible a relationship between the world of the living and that of the dead, but not for having entered into a pact of a diabolical nature.

Furthermore, according to what reported by Map, the wandering of the Herlethingi family would have ceased in 1155, the first year of the reign of Henry II, leaving the story a double reading of a political matrix: on the one hand a critique of the Plantagenet court and its mobility, typical of feudal courts, and, on the other hand, a possible defense of the new dynasty, since the return of the ancient king of the Bretons would symbolically represent a threat to the new king [6].

A little later, in France, in the diocese of Beauvais, the Cistercian Elinando of Froidmont, he describes in the work De cognitione his, a very precise and lucid representation of Hellequin's gang, also questioning the etymological nature of the name of his boss, Hellequin.

During the twelfth century, in fact, there are numerous traces of the army of the dead, and equally numerous are the transformations of the name with which it is indicated depending on the geographical area in which it appears. Elinando, through one of the two testimonies he reports, reports that the name Hellequinus, to indicate the leader of the army of the dead, is an incorrect term, since it should be said Karlequinus, from the name of King Charles the Fifth, who, through the mediation of Saint Dionysius, had recently been freed from the atonement of his sins [7]. In this case Elinando operates an etymological rationalization, based on the homophony of the two names, but also a juxtaposition of the host to the Carolingian dynasty, approaching the narrative content of Walter Map's work, that is, comparing the fantastic army to a court that really existed, also supporting the recent cessation of the apparitions of Hellequin's gang.

A particularly interesting trait in Elinando's narrative is the ambiguous characterization ofexercitus mortuorum, "More than an army of the damned, it seems a sort of itinerant purgatory [...], although hellish, it offers some further hope of salvation to the souls it drags with it" [8]. Such a reading could compare the so-called "disappearance" of Hellequin's gang to the "birth of purgatory", since theexercitus mortuorum he would no longer have reason to exist due to the exhaustion of his penitential function [9].

Always in a Cistercian environment, and more or less in the same years, the monk Herbert of Clairvaux, speaks again of the gang of Hellequin in Libri de miraculis cistercensium monachorum libri tres, but, differently from the pre-existing tradition, in this testimony the members of the team are not knights but craftsmen, men who carry out manual work, who, flying in mid-air and immersed in a thunderous din, are tortured with their own tools to their trades [10].

At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, Gervasio of Tilbury he composed the opera Otia imperialia (1211), intended for the delight of Henry II of England and including a large collection of mirabilia. Among these, many concern the collective apparitions of the dead in the most disparate geographical places of Europe, Gervasio collects testimonies from Catalonia to Sicily: no place is exempt from the presence of the army of the dead.

Starting from the XII century in the south of the Italian peninsula ed in Sicily the Arthurian legend spread through the influence of the Norman cavalry. The historic refuge of Arthur, Avalon, finds its local transposition in Etna [11], since ancient times considered the entrance to the underworld and which, in contemporary times, other authors compared to purgatory. Gervasio, present in the Sicilian territory at the service of William I, is the first among the writers to give voice to this new Arthurian residence [12] and collecting local testimonies he tells of the splendid court of Arthur in the center of Etna, which brings to mind the legends and traditions concerning the Wild Hunt present in Great Britain, which he calls, not surprisingly, Arthur family.

A little later than Gervasio is the Cistercian Cesarius of Heisterbach that, in his Dialogus miraculous (C.1223), takes up the theme of the Arthurian court in Etna degli Leisure, but with darker and more macabre hues compared to those of his predecessor, certainly adding to the narrative a negative interpretation of the figure of Arthur. Furthermore, Cesario, in another story, reports that on the slopes of the Sicilian volcano there were many who heard demonic voices; these attestations lead the Cistercian monk to affirm that Etna is "the mouth of hell" and not "purgatory". Reading Cesario's work directs the interpretation in a negative key: Etna reappears in its ancient infernal form and Arthur too appears progressively demonized, as it happens at the same time for Hellequin. The two legendary characters, Arthur and Hellequin, begin to be confused in contemporary testimonies.

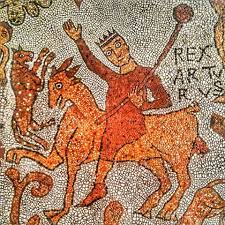

An important trace of this transfiguration of value can be found in the Mosaic depiction of Arthur on the floor of the cathedral of Otranto, datable between 1163-1165 ca., in which the mythical sovereign, recognizable through an inscription, is represented riding an animal, probably a ram or a goat. This work gives rise to ambiguous and discordant interpretations between them: on the one hand a positive reading justified mainly by the context in which it is inserted, that is, alongside the representation of the sacrifice of Abel and, on the other, a reading in a negative key, mainly linked to the strictly unfavorable decoding of the animal ridden by Arthur [13].

In 'example n˚365 of Tractatus de diversis materiis praedicabilibus of the Dominican preacher Stephen of Bourbon the two names, Arthur and Hellequin, the infernal elements within the legend overlap and increase. Like Gervasio, Stefano places Arthur's abode inside a mountain but, the wonderful Etnean palace of Arthur described in the Leisure, it turns into a court with satanic features; significantly, the torma is defined by Stefano as Allequini family vulgariter vel Arturi.

The fabulous and ambiguous aspect of the mirabilia dissolves in the warning function which theexample: the dead have officially become demons and in the words of J.-C. Schmitt, "the utopia of an Arthurian kingdom that has all the characteristics of a land of the Bitch is incomprehensible [...] on the contrary, the story highlights the power of demons over coarse spirits gripped by the desire of the flesh [...] the army of the dead has become only an army of demons and, if it remains mobile, it connects to a fixed and central place of sexual and diabolical addictions " [14]. As noted by A. Graf, from the story of Gervasio to that of Stefano, we are witnessing a rewriting of the progressively infernalized text [15], to coincide with the simultaneous localization and stabilization of purgatory.

In little more than half a century the king of the dead, whether you want to call Hellequin, Herla, or Arthur, has quickly become a demonic figure and the example moralizing have replaced the taste of the marvelous gods mirabilia, removing the gang of Hellequin from its penitential function, without however uncertainty, as demonstrated by the testimony of one of the most important representatives of scholastic theology, the bishop of Paris, William of Auvergne, who, in his Of the Universe (1231-1236) proposes a real theory of Hellequin's gang.

According to the conception of William of Auvergne theexercitus mortuorum it is subject to a double and obscure interpretation: it could be a group of souls in pain or evil spirits, who at night only take on the appearance of knights, as they are only "signs" without materiality; these apparitions preferably take place at the crossroads which, due to their border position, are among the most sordidly crossed places. It is precisely in these places that the living become aware of the pains suffered by souls awaiting salvation. According to the words of the French theologian, it would be God himself who allowed these apparitions, in such a way that those who abuse violence witness with terror the representation of what belongs to those who have acted similarly.

Through the words of William of Auvergne we witness the "ideological function that the Church assigns to the gang of Hellequin, in a moral mirror that it tends to those who make violence their profession" [16], explicitly linking it to purgatory. As noted by JC Schmitt [17]:

“We can ask ourselves whether the development of the doctrine of purgatory, understood as a particular and defined place of individual expiation of souls in the hereafter, has not destroyed the possibility of a purgatory itinerancy. "

This latter attempt to fix the Mesnie hellequin in purgatory, however, he did not succeed completely, since for the Church and for ecclesiastical culture it was necessary and fundamental to enclose the ghosts and collective apparitions in a precise and safe place and the motif of the Wild Hunt was assimilated to the universe of beliefs and "evil spirits".

In the thirteenth century and in the literature of the example therefore triumphs the moralizing reading and demonization of the gang Hellequin, whose king, Hellequin-Arthur, has become the ruler of hell, the devil himself. This demonized interpretation of the army of the dead and of the folkloric tradition connected to it will be largely nurtured by theologians, inquisitors and demonologists over the next two centuries, until it assumed the monstrous physiognomy of the night flight and the witchcraft sabbath [18].

The mask of Hellequin

In the medieval West masks play a fundamental role in folkloric traditions, linked to different moments of the calendar, to the ritual manifestations of the "cycle of life" and hullabaloo [19]. Ecclesiastical culture has, from the beginning, tenaciously condemned masquerades and masks as a double sign, which hides the one who wears the mask and evokes the other, whose appearance the mask outlines. The Church conceives the mask as imago, figure which refers to something else and falls within the type of mirror images, inducing the wearer to a real transformation. This similitude of the mask is defined as illegitimate since the only one similitude granted is that of man born "in the image of God": masking is diabolical and, in the medieval West, the devil and the mask tend to be equivalent, since both have the capacity to transfigure men and themselves [20]. The Church, therefore, reading in the masquerades a deception with respect to theological truth, sanctions its irrevocable condemnation and persecution.

Medieval masks have not been preserved until our days and we only know them by virtue of the description made of them in the texts and images, but coming almost exclusively from the official religious culture. [21]. Among the most interesting sources, an important role belongs to the miniatures accompanying manuscript 146 of the Biliothèque Nationale in Paris, an interpolation of the Roman de Fauvel of Gervais du Bus by Chaillou de Pestain, dating back to the first half of the fourteenth century. In the text we see a richly detailed representation of the folkloric rite of the hullabaloo, following Fauvel's wedding with Vanagloria and, in the roaring crowd, the author identifies a character with the leader of the troop of the dead, Hellequin [22]:

I believe it's Hellequin

And all the others his gang

Who follows him all furious

The miniatures following the text depict the masks and disguises of the participants in the hullabaloo and, in one of these, we can identify the character who recalls Hellequin and his retinue of deaths to the memory of the author. The king of the dead is in fact represented on horseback and carries, resting on his ears, upturned bird wings [23], while the dead are depicted masked and inside two coffins.

Manuscript 146 Bnf, in addition to presenting itself as an exceptional document, is the oldest iconographic documentation of one charivari, brings to light the reason for the Mesnie hellequin in all its age-old enigmaticity. The miniatures convey all the ambiguity that characterized Hellequin's gang, as "they are not just the appearance of a charivari nor of the Mesnie hellequin, but they show both at the same time, one through the other [...] the image shows at the same time the spectacle and what it evokes: an apparition " [24]. The images of the manuscript perfectly translate the ambivalence of the ritual of masks and its belief, as the author believes to see in hullabaloo la Mesnie Hellquin, as the masks of the procession represent the dead of the community.

In the folkloric ritual of hullabaloo the masks, in addition to representing the dead returning from the community, represent "the necessity for the masquerade of this return [...] andplaying the role of the dead requires a terrible mask, in which all the features are mixed, elusive and even more disturbing» [25] and therefore, these masks cannot be worn with impunity and be alone ludus, but they recall the diabolical area, which the author rightly evokes referring to Hellequin's Masnada.

Never, in the texts which, starting from the XNUMXth century, mention theexercitus mortuorum, the characters that are part of it are described with demonic or monstrous features as happens in the miniatures of the BN manuscript fr 146. This change, this masking of the spirits is a novelty that began in the thirteenth century, when the Church demonized the folkloric tradition of the ranks of the dead and above all when, from the stories of mirabilia and by example, we move on to the ritual or theatrical representations of the Mesnie hellequin [26].

Starting from the XNUMXth century, the Mesnie hellequin it is transformed and reduced, in the theatrical staging, to its representative par excellence: Hellequin, who, in harmony with the rules of medieval theater, wears a mask, since only diabolical characters are allowed to wear it. Hellequin, from head of the army of the dead, gradually changes, transforming himself, in the theater of the sixteenth century, into the figure of Harlequin, whose name and horned mask remain as the only traces of his ancestor, the king of the dead [27].

At the origins ofexercitus mortuorum:

some research guidelines

In medieval times the written tradition bears the traces of the army of the dead from the XNUMXth century, starting from Ecclesiastical history by the Norman historian Orderico Vitale and, in the following centuries, literary texts from all over Europe report the apparitions of the ranks of the dead. Apparitions are defined more or less everywhere with appellations relating to the semantic field of "furious army"(Wuthischend Heer, Mesnie furieuse, Mesnie Hellequin) and that of the "Wild Hunt"(Wilde Jagd, Chasse sauvage, Wild Hunt, Chasse Arthur).

Despite the endless discussions that have taken place on the etymology of the name Hellequin (or Herlequin or Helething) there are still few doubts about its Germanic root, referring to the army (Heer) and to the assembly of free men, those who can bear arms (thing) [28]. The various forms and figures ofexercitus mortuorum were also interpreted in the light of bands of young warriors (Mänerbünde) widespread among the ancient Germans and through the reference to the god Wotan we wanted to read the ancient permanence of the warrior vocation of Germanic males [29].

Jacob grimm, pioneer of research on the reason forexercitus mortuorum, in its Deutsche Mytologie, confronted the substitution mechanisms underlying the figure of the king of the dead, who from time to time is identified in the testimonies with historical characters (Federico II, Ugo Capeto, Carlo V), legendary (Arthur, Herla, Arlecchino) or mythical (Wotan). The German folklorist indeed recognized in Wotan the original conductor, as the supreme deity of the Germanic pantheon, deeply linked both with the world of the dead and with war. The myth at the origin of the apparitions witnessed starting from the XNUMXth century would therefore have been that of the army of the dead following the god.

Scholars contemporary to Grimm gave the Wild Hunt a naturalistic interpretation linked to the wind and the power of the hurricane, while others brought it back to the rituals of expulsion of the winter aimed at restoring the fertility of the land. Since the twentieth century the hypothesis of the mythical background linked to the god Wotan and the leagues of the Germanic warriors has prevailed, acquiring more and more scientific dignity, finding one of its most illustrious explanations in Kultische Geheimbünde der Germanen, published in 1934 by Otto Höfler; volume in which the accounts of the apparitions were read as clear evidence of the existence of bands of warriors mystically united with the army of the dead and its leader, Wotan [30].

Subsequent research focused on two main lines: on the one hand, an attempt was made to reconstruct the meaning of the myth, in its original and antecedent form compared to the Christian re-elaboration during the medieval centuries, including the studies endorsed by C. Ginzburg, from we tried to identify something else the ritual plan of which theexercitus mortuorum it was the mythical and narrative correspondent, mainly traced in the hullabaloo. An exception to these two main currents is finally provided by the work of J.-C. Schmitt, who, in addition to having proposed an extraordinary synthesis and periodization with respect to the reason for the Mesnie hellequin, critically addresses the continuous changes that are made to the sources, with particular attention to the re-functionalization and change of the myth during the course of the Middle Ages.

In conclusion, after analyzing the attestations of the myth, it is possible to read the motif of the Wild Hunt or of Hellequin's Masnada [31]:

«[…] In its malleability in the continuous changes driven by always different solicitations and needs coming from the most diverse levels of society. Its main feature is liminality; in fact, the myth stands on the border between the living and the deceased, society and the individual, orality and writing, secular and religious culture. In this sense, the mythical theme is configured as a privileged observation point for reading social and cultural transformations of crucial importance. It is precisely its flexibility, its ability to convey ideas and messages that are also profoundly different from each other and, at the same time, to maintain its precise identity, constitutes the key to understanding its duration and effectiveness over the centuries. »

Note:

[1] JC Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West, Laterza, Bari-Rome, 1988, p. 152.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Ivi, p. 161. Map's narrative is inspired by medieval folk tales of "visits to Fairyland"; in this regard cf. M. Maculotti, Access to the Other World in the shamanic tradition, folklore and "abduction", AXISmundi.

[4] The Aarne-Thompson system is an analytical method of classifying fairy tales and folk tales. The system is based on an index of recurring motifs in the fairy tale, allowing it to be classified according to the themes found there. It was first developed by the Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne and later expanded by the American Stith Thompson. See S. THOMPSON, The Folktale, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1946 (it., The fairy tale in popular tradition, Milan, Il Saggiatore, 1994).

[5] See JC Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West, op. cit., P. 163.

[6] In this regard see JC. Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West, op.cit., p. 173. Schmitt also hypothesizes a relationship between the legend of Herla and the legend of Arthur, as both were used for political purposes in the same period. In fact, the threats of the ancient kings against the new Plantagenet dynasty would be similar. The supposed discovery of Arthur's burial in Glastonbury Abbey dates back to 1191 and the reign of Henry II, in which Avalon Island was identified, the refuge where the king of the Bretons would have found shelter. With this test, an attempt was made to eradicate all hope in the return of the legendary king, while in the following decades the English monarchy tried to take possession of the entire Arthurian symbolism. The belief of Arthur's possible return, however, failed to dissolve.

[7] JC Schmitt, Spirits and ghosts in medieval society, op. cit., p. 158.

[8] Ivi, P. 157.

[9] J. Le Goff, The birth of Purgatory, op. cit., p. 75. On the "birth" of Purgatory in the Celtic area and its penitential function, cf. Jean Markale: the Other World in Druidism and Celtic Christianity, AXISmundi.

[10] K. Meisen, The legend of the furious hunter and the wild hunt, op. cit., p. 60. C. Ginzburg observes that this singular example of the collective apparition of the dead can be traced back to the monastic hostility towards the "mechanicae artes" and those who practiced them, Cfr. C. Ginzburg, Charivari, youth associations, Wild Hunt in «Historical Notebooks», vol. 17, no. 49 (1), 1982, pp. 164-177.

[11] The variation of the legend of Arthur in Etna seems to have a Germanic and not a Sicilian-Norman derivation. Compared to the original home of the wounded Arthur, the island of Avalon, the poetic variations introduce other islands for his stay. Furthermore, in the Germanic tradition, the version of the mysterious palace inside a mountain spreads. Northern mythology is full of examples of heroes and refugees in the hollows of the mountains (god Wodan, Frau Holda, Frau Venus…). Likely therefore seems to be a Norman variation and not an original Sicilian trait. Typically Greek-Roman and Sicilian is instead the tradition of Etna as a wonderful place, the site par excellence of mythical episodes and as access to the kingdom of the underworld and seat of the forges of Vulcano. The Sicilian hypothesis of the location of Arthur's marvelous court in a place that the southern tradition classified as the mouth of Hell therefore seems incongruous. See A. Graf, Myths, legends and superstitions of the Middle Ages, Mondadori, Milan, 1984, p. 333. On the topos of the ancient sovereigns in "exile" or in "coma" in an atemporal dimension, waiting to awaken and return to power, cf. M. Maculotti, Apollo / Kronos in exile: Ogygia, the Dragon, the "fall", AXISmundi.

[12] A.Graf, Myths, legends and superstitions of the Middle Ages, op. cit., p. 324.

[13] For an in-depth reading of the different interpretations see C. Settis Frugoni, For a reading of the floor mosaic of the cathedral of Otranto, in «Bulletin of the Italian Historical Institute for the Middle Ages and Muratorian Archives», n. 80, 1968, pp. 213-56.

[14] JC Schmitt, "Superstitious" Middle Ages, op. cit., p. 127.

[15] A.Graf, Legends, myths and superstitions of the Middle Ages, op. cit., p. 330. On the "demonization" of the ancient pagan cults by the ecclesiastical authorities, cf. M. Maculotti, From Pan to the Devil: the 'demonization' and the removal of ancient European cults, AXISmundi.

[16] JC Schmitt, Spirits and ghosts in medieval society, op. cit., p. 163.

[17] Ibid.

[18] C. Ginzburg, Charivari, Youth Associations, Wild Hunt, in «Quaderni Storici», vol. 17, no. 49 (1), 1982, pp. 164-177.

[19] Since the fourteenth century the hullabaloo (In Italian flared, capramarito) presented itself as a form of protest made by a group of men, usually young, who shouting and making a great noise expressed their disapproval, on the occasion of "unequal" marriages, for example a considerable difference in age between the two spouses, the second marriage of widowers or on the occasion of adulterers. In doing so, the participants in the hullabaloo they criticized behaviors that violated social norms. See Margareth Lanzinger, The choice of a spouse. Between romantic love and forbidden marriages, in «Historically», 6 (2010), no. 4. For further information on the "masquerades" and "ritual battles" that took place on such occasions, cf. M. Maculotti, The archaic substratum of the end of year celebrations: the traditional significance of the 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany e Metamorphosis and ritual battles in the myth and folklore of the Eurasian populations, AXISmundi.

[20] JC Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West, op. cit., p. 213.

[21] The search for an exact representation of the medieval mask is therefore unlikely, since the filter of the sources unequivocally belongs to the learned culture.

[22] BN ms. fr. 146 quoted in JC Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West, op. cit., p. 221.

[23] Ruth Mellinkoff proposes an iconographic reading of figures of beings with upturned wings on their heads to symbolize evil and its incarnations; this iconography is widespread in the atéliers of northern French and German miniatures starting from the XNUMXth century, or since the gods of classical antiquity were rediscovered and demonized, attributable above all to a reuse of Hermes-Mercury in a negative key. See R. Mellinkoff, Demonic Winged Headgear, in «Viator», 16 (1985) pp. 367-406, quoted in M. Lecco, The 'Charivari' of the 'Roman De Fauvel' and the tradition of the 'Mesnie Hellequin'in «Mediaevistik», vol. 13, 2000, pp. 55–85.

[24] JC Schmitt, Religion, folklore and society in the medieval West, op. cit., p. 223.

[25] Ivi, P. 229.

[26] Ivi., P. 227.

[27] An in-depth analysis of the evolution of Hellequin in Arlecchino, protagonist of the commedia dell'arte in Lucia Lazzerini, Harlequin, flies, witches and the origins of popular theaterand in «Middle-Latin and vulgar studies», XXV, 1977, pp. 93-155.

[28] C. Ginzburg., Nocturnal history, a deciphering of the Sabbath, Einaudi, Turin, 1989, p. 78.

[29] O. Höfler, Kultische Geheimbünde der Germanen, Frankfurt a. Main, 1954 quoted in C. Ginzburg, Night story, op. cit., p. 79. For a comparative analysis of the mythologems concerning the Army of the Dead and the Wild Hunt, cf. G. Mollar, The "Ghost Riders", the "Chasse-Galerie" and the myth of the Wild Hunt, AXISmundi.

[30] Cf.. A. Flower, Furious line-up and wild hunt: a discussion and some perspective, in "Historical notebooks", 116 (2004), pp. 559-576. On Wotan as conductor of the Wild Hunt, cf. also M. Maculotti, Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun', AXISmundi.

[31] Ibidem.

Bibliography:

- Brown, P. The cult of saints: the origin and spread of a new religiosity, Einaudi, Turin, 1983.

- Duby, G. The mirror of feudalism. Priests, warriors and workers, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1987.

- Ginzburg, C. Nocturnal history, a deciphering of the Sabbath, Einaudi, Turin, 1989.

- Graf, A., Myths, legends and superstitions of the Middle Ages, Mondadori, Milan, 1984.

- Le Goff, J. The wonderful and the everyday in the medieval West, Laterza, Rome-Bari 1983.

- Meisen, K. The legend of the furious hunter and the wild hunt, Edizioni dell'Orso, Alessandria, 2001

- Schmitt, J.-C. Spirits and ghosts in medieval society, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1995.

- Schmitt, J.-C., Religion, folkore and society in the medieval West, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1988.

- Schmitt, J.-C., "Superstitious" Middle Ages, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1992.

Contributions in magazine:

- Ginzburg, C. Charivari, youth associations and wild hunting, in «Historical Notebooks», vol. 17, no. 49 (1), 1982, pp. 164-177.

- Fiore, A. Furious line-up and wild hunt: a discussion and some perspective, in "Historical notebooks", 116 (2004), pp. 559-576

- Lanzinger, M. The choice of a spouse. Between romantic love and forbidden marriages, «Historically», 6 (2010), no. 4.

- Lazzerini, L. Harlequin, flies, witches and the origins of popular theaterand in «Middle-Latin and vulgar studies», XXV, 1977, pp. 93-155

- Lecco, M. The 'Charivari' of the 'Roman De Fauvel' and the tradition of the 'Mesnie Hellequin' in «Mediaevistik», vol. 13, 2000, p. 55–85.

9 comments on “Hellequin's Masnada: from Wotan to King Arthur, from Herla to Harlequin"