Two centuries after its publication, ETA Hoffmann's "Man of the Sand" is still today one of the literary works indispensable for understanding the poetics of the "uncanny", destined to influence the psychoanalytic theories of Freud and Jentsch, the works of Hesse and Machen, the films of Lynch and Polanski.

di Marco Maculotti

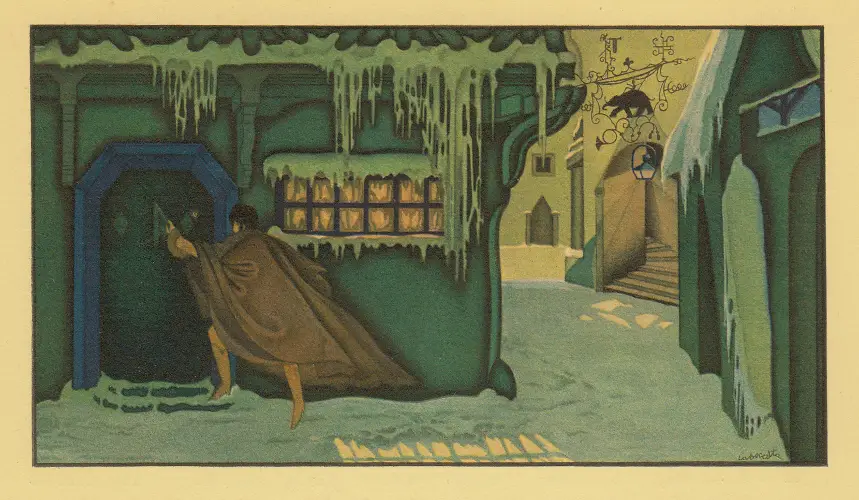

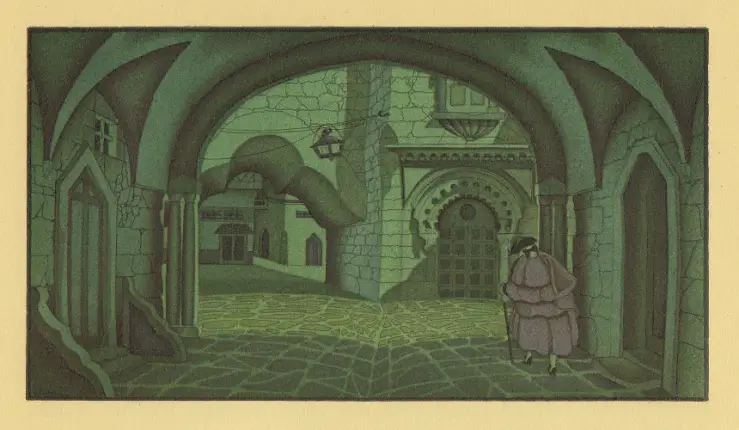

image: Mario Laboccetta, from “Tales of Hoffmann”, 1932

part I of II

Exactly a century has passed since the publication of the essay (The unheimlich, 1919) [1] , whereby Sigmund Freud, illustrating the category of the "Uncanny" (unheimlich) in psychoanalysis and literature, he elected Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776 - 1822) as its highest representative, with special mention a Der sandmann, a masterpiece of gothic-surreal literature, included in the Night pieces ("Night tales"), published in two volumes in 1816 and 1817 [2]. And they are, therefore, well two the centuries that separate us from the publication of these short stories of the genius - albeit today, inexplicably, on the verge of oblivion - German writer. Despite the time that has elapsed since their diffusion, the "Nocturnes" still retain unchanged all the ambivalent charm that already accompanied them in the early decades of the nineteenth century, in a world - as you can imagine - significantly different from ours.

Yet it is not believed that Hoffmann's fame was affected by the change in Zeitgeist between the nineteenth century and the third millennium: it would be absurd to imagine that the average reader of the time in which Hoffmann lived (a time in which, let us remember, there was still nothing remotely comparable to the psychoanalytic theory, already present in nuce in "The Sandman" and others Night pieces, equally in the Freudian components as in the Jungian ones) had more suitable intellectual tools than those in our possession to understand the extraordinary, eclectic, unlabellable artistic vein of the German man of letters. Of course ETA Hoffmann fu a man of his times, and indeed one of the most significant and iconic of all: nevertheless, as often happens to the most crystalline geniuses, he was at the same time projected much further than the "world view" of the time .

A few decades ahead of EA Poe and about a century ahead Arthur Machen and HP Lovecraft, Hoffmann managed in numerous stories to make the "uncanny" the real driving force, the secret element of his art: his labyrinthine intuitions and obsessions not only inspired great colleagues like the aforementioned, and also Dostoevsky, the most "esoteric" Hermann Hesse (The steppe wolf e Demian) and Schnitzler, but also broke into the imagination of some of the most relevant film directors of our day, such as David Lynch and Roman Polanski. In this article we intend to highlight some observations that make us lean towards this thesis, and on which the reader is invited to take an autonomous position.

CONCEPTUAL AMBIVALENCE OF THE "DISTURBING"

If we want to better understand what is meant by "disturbing" we must necessarily start from Freud's essay and the previous one, quoted by the Viennese, by the German Ernst Jentsch. In the first place - on this they both agree -, is to be seen in the German word unheimlich ("Uncanny") the antithesis of Heimlich (from heim, "home"), native ("Homeland, native"), and therefore "familiar, habitual", «And it is obvious to deduce that if something is frightening it is precisely because non it is known and familiar ". However, Freud adds [3]:

«Jentsch all in all stopped at this relationship between the uncanny and the new, the unusual. He identifies the essential condition for the disturbing feeling to take place in intellectual uncertainty. The uncanny would always be properly something in which, so to speak, one cannot understand. "

For his part, therefore, the Austrian goes further, identifying a further nuance of the term Heimlich which at first glance could appear completely in contrast with what has been said so far: this term is used, in fact, also to indicate something "hidden, kept hidden, so as not to make it known to others or not to let others know the reason for which it is intended to be concealed. Do something Heimlich (behind someone's back) ». He then concludes [4]:

«… We are warned against the fact that this term Heimlich it is not unique, but belongs to two circles of representations which, without being antithetical, are nevertheless quite alien to each other: that of familiarity, of ease, and that of hiding, of keeping hidden. In current use, unheimlich it is the opposite of the first meaning, but not of the second. "

Nevertheless, he notes, part of the doubts thus raised are clarified by the indications contained in the German dictionary of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm [5]:

« From the meaning of "christmas", "domestic" also develops the concept of: stolen from foreign eyes, hidden, secret [...] Heimlich as for knowledge: mystical, allegorical; meaning "Heimlich", mysticus, divinus, hidden, figuratus... subtracted from knowledge, unconscious [...] The meaning of "Hidden", "dangerous", which emerges [...] develops further, so that "Heimlich"Usually takes on the meaning of"unheimlich". "

This contrary conjuctio between "Heimlich" is "unheimlich"Will be realized with admirable results in the work of the already named Welsh writer Arthur Machen [6], in whose stories the experience of the Sacred is both terrifying and ecstatic, in line with the subsequent insights of Rudolph Otto (Das Heilige saw its publication in 1917, exactly one century after Hoffmann's "Nocturnes"): the encounter with the Divine, the "Totally Other", can only be at the same time Mysterium Tremendum and super-earthly bliss [7].

It will be noted how, in Hoffmann's stories, the "uncanny" is often connected to a dimension that can well be defined familiar, domestic: the abhorred delusional mysteries encountered by the protagonists of his stories (to a certain extent the author's alter-ego) have more often than not to do with family dramas, tragic situations that, precisely by virtue of their being Heimlich (i.e. domestic, private, intimate) they end up becoming necessarily, when you insert a foreign element (usually the protagonist or narrator) unheimlich: it is therefore necessary to keep them hidden as much as possible, to hide them away from prying eyes. He will be the protagonist on time Hoffmannian to "put his beak into it", as they say, attracting to him malevolent influences that he would have done better not to investigate - a narrative expedient, this, which will then typically become Lovecraftian. And, in this regard, the observation of the Schelling:

« unheimlich it is all that should have remained secret, hidden, and instead surfaced. »

And it is precisely this situation unsafe, aforementioned feeling of impending doom on the characters of Hoffmann's stories (but also of Machen, Lovecraft, etc.) - this feeling pushed towards an inevitable destiny, as if the entire path of existence had somehow been guided by someone or by qualcosa towards a predetermined outcome - to constitute one of the main reasons not only for the poetics of ours, but in general for all the novelists of the literary vein of the "Supernatural Fantastic" or, better said, of the "Weird". In fact, it should be noted with Thomas Ligotti is [8]:

"[...] the English adjective weird, which stands for "mysterious, supernatural, magical", if substantiated it can mean "fate" [...] Perceiving that all our steps had to lead us to a predetermined appointment, understanding that we are face to face with something that perhaps has always been waiting for us: this is the necessary scaffolding, the skeleton that supports the strangeness of weird […] This strange sense of fate is undoubtedly an illusion. And the illusion creates the same matter that fills the skeletal scaffolding of the mystery. It is the essence of dreams, of fever, of unprecedented encounters; envelops the bones of mystery and fills their various forms and fills their many faces. »

And, not surprisingly, among the greatest "mystery stories based on crucial enigmas", Ligotti cannot fail to mention Der sandmann by ETA Hoffmann.

"THE MAN OF THE SAND"

Even before Freud, the aforementioned German physician and psychologist Ernst Jentsch [9] elected Hoffmann to the level of "Master of the uncanny", justifying this assertion by mentioning one of the most significant aspects of "The Man of the Sand": «One of the surest devices to cause disturbing effects through the story - writes Jentsch - consists in keep the player in one state of uncertainty as to whether a given figure is a person or an automaton»[Cors. ns.].

But there is more: it unveiling of the fact that behind whoever was thought to be a person in flesh and blood (Olimpia) there is only a doll suggests implicitly e unconsciously (or better subconsciously) to Nataniel the possibility of being himself, in the end, one puppet, and so too, in the conclusion of the story, his fiancée Clara. This is also pointed out by Jentsch, according to whom we are faced with an example of "uncanny" when [10] «the individual stops appearing integrated into his identity and takes on the appearance of a mechanism [exactly how Nataniele behaves in the end of the story, as "remote controlled" by the Mephistophelic Coppelius, ed], a set of parts made as they are made, which is a clockwork process rather than an immutable being in its essence ».

The same can be said by taking it as a model theepileptic which, similarly to the automaton, flashes into the subconscious mind of the observer the impression that the human being is nothing more than a clockwork device, susceptible to failing and breaking [11]:

«Not only is the epileptic perceived as something disturbing by the observer […], but the observer perceives the uncanny also in himself, because the mechanical nature of any human body has been clarified and, by extrapolation, the fact that “mechanical processes take place in what until then he was used to considering a unitary psyche”. "

However, despite being the reason for the woman-automaton central to the economy weird di Der sandmann, other and no less important architects were brought into play by Hoffmann to weave as closely as possible the "network of the uncanny" (the wyrd of weird): this is noted by Freud, who nevertheless - as per usual - ends up giving a reading almost exclusively Oedipal. One of these narrative expedients is the division of the story into two distinct "acts" in temporal terms: the first is narrated from the point of view of Nathaniel as a child, the second from that of the adult.

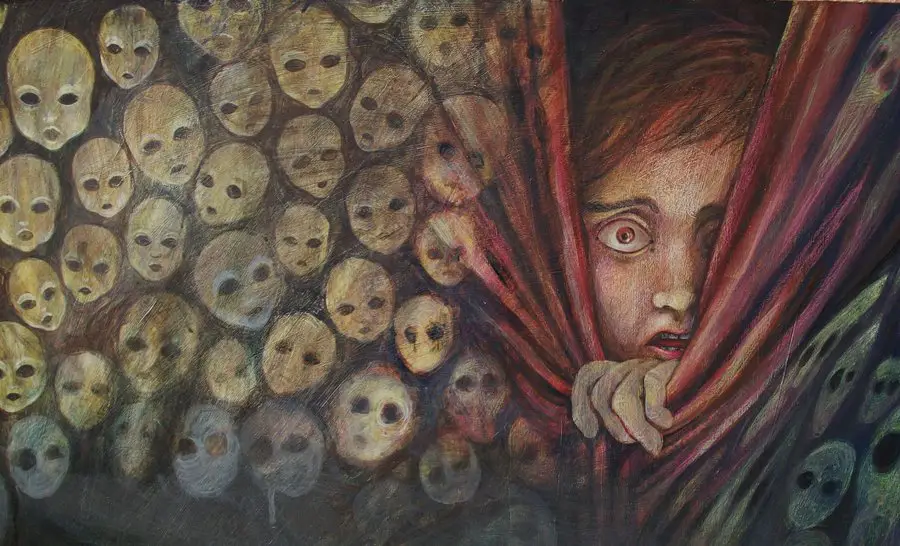

Little Nataniel's voice makes us aware of it some chilling memories of his childhood, linked to the death of his father and the legend of the "Sandman" (or "Sandy Wizard"), A sort of" Black Man "feared by N.'s mother to make him go to bed early which would punish disobedient children throwing sand in their eyes [12]. Subsequently, the child will identify the identity of the "bogeyman" in the person of theCoppelius lawyer, a repellent individual even in physiognomy (other topos Hoffmannian) that of occasionally visits his father. The two entertain themselves in mysterious operations of evident occult-alchemical character in front of a flaming furnace. One evening, having gained courage, little Nataniele enters his father's study with the desire to spy on the enigmatic practices [13]:

Little Nataniel's voice makes us aware of it some chilling memories of his childhood, linked to the death of his father and the legend of the "Sandman" (or "Sandy Wizard"), A sort of" Black Man "feared by N.'s mother to make him go to bed early which would punish disobedient children throwing sand in their eyes [12]. Subsequently, the child will identify the identity of the "bogeyman" in the person of theCoppelius lawyer, a repellent individual even in physiognomy (other topos Hoffmannian) that of occasionally visits his father. The two entertain themselves in mysterious operations of evident occult-alchemical character in front of a flaming furnace. One evening, having gained courage, little Nataniele enters his father's study with the desire to spy on the enigmatic practices [13]:

«[…] Both of them wore long black tunics […] My father opened the doors of a built-in wardrobe; but what for so long I had thought of as a cupboard was instead a black cave in which stood a small hearth. Coppelius walked over and sparked a crackling blue flame. There were strange objects around. My God, how transfigured my father was as he bent over the fire! One would have said that a horrible and excruciating pain had distorted his sweet and honest features, transforming him into an ugly and repulsive demon. He resembled Coppelius, who with incandescent pincers removed sparkling substances from the dense smoke which he then hammered furiously. I seemed to see many human faces around them, but without eyes: instead of eyes they were black and deep cavities. - Here the eyes! Here the eyes! Cried Coppelius in a hollow, thunderous voice. »

However, it happens that, in the middle of the "session", Nataniele ends up being discovered by Coppelius, who threatens to throw in his eyes a handful of incandescent grains from the ceremonial embers. Only a lightning and desperate appeal from the father manages to make the sinister figure desist from carrying out such barbarism: but what happens later, at least according to the boy's confused memories, is even more disturbing [14]:

Coppelius laughed loudly and said: 'Keep your eyes, the boy and whine your part in the world; but let's take a closer look at the mechanism of the hands and feet! — So saying he squeezed my joints tightly making them crunch and unscrewed my hands and feet and was putting in place now those, now these. »

Following this traumatic experience (and apparently undecipherable rationally), Nataniele falls unconscious and remains convalescing for months. His father, on his part, will die a year later, in the midst of another alchemical experiment with the diabolical lawyer Coppelius. This concludes the part of the story dedicated to the protagonist's childhood.

In the second "act", so to speak, the actors change but not the masks: to replace the deceased father we find Professor Spallanzani, professor of physics and mechanical; in place of the lawyer Coppelius there is the almost namesake optical and barometer seller Giuseppe Coppola [15]. Of course, the lawyer Coppelius and Coppola are the same entity, and it will be the Italian optician himself - whom the boy himself immediately reconnects, right from the physiognomy, to the feared Sandy Wizard - to sell him a telescope which will contribute decisively to plunging the protagonist towards the abyss of madness: this is why the telescope, but also the mirror in other Hoffmannian tales, opens new glimpses to the organ of sight, in a literal and at the same time esoteric sense.

It will in fact be thanks to it that Nataniele will get into the insane habit of spying on Olimpia, daughter of Spallanzani, a cold girl with whom the young man falls madly in love, temporarily forgetting his girlfriend Clara. And yet, despite the Platonic exaltation of Nataniel, something "disturbing" is looming on the horizon; his friend Sigismondo, in particular, tries to warn him, saying: “How is it possible that a smart boy like you fell in love with that face of wax, of that wooden doll over there? " [16]. Olimpia, in fact, finally turns out to be not a girl in flesh and blood, but an artificial automaton: here we are faced with a modern update of the myth of the "corpse bride". Lo shock definitive comes when Nataniele, arriving at Spallanzani's house to ask for the hand of his "daughter", witnesses a furious discussion between the mechanic and Coppola, a quarrel during which the two they tear apart his beloved Olympia. This is how its nature as an automaton is defined once and for all, and it is specified that Spallanzani entered the mechanism (the'clockwork) and Coppola gli eyes [17]:

«Nataniele was dumbfounded: all too clearly he had seen that the blue face of Olympias was without eyes; instead of eyes dark caves; she was an inanimate doll. Spallanzani [...] began to shout: - [...] Coppelius ... he stole my best automaton ... twenty years of work ... I put my body and soul into it ... the watchmaking ... the word ... the steps ... all mine ... the eyes ... the eyes stolen from you ... »

At this point, Spallanzani throws Olimpia's bloody eyes on the chest to Nataniel, which were lying on the ground, after having revealed to him that Coppola Ii had stolen from him. Understandably, the student is seized by a new attack of madness: in his delirium the memory of his father's death intersects and mingles with the trauma he has just experienced and screams [18]: «Uh… uh… uh! Circle of fire… circle of fire… spin round… cheerful… cheerful! Wooden puppet, uh, beautiful doll, turn around! ". It throws itself then, out of itself as a epileptic, on the mechanical, trying to strangle him.

After a long period of rehabilitation, and after reuniting with his girlfriend Clara, one last episode of delirium will put an end to Nathaniel's days. During a visit to the top of a tower, he notes with the telescope the presence of the abject lawyer Coppelius in the crowd and instantly attacks her partner, with the clear (albeit inexplicable) will to make her fall, barking madly: «Turn, wooden doll ... Turn turn, wooden doll ... Wooden circle, turn ... Turn turn, circle of fire ... O beautiful eyes, beautiful eyes![19]. Last but not least, after this final crisis, theactor literally leaves the scene: as if guided by an external will (which is supposed to be that of the revived Coppelius), he throws himself down, crashing to the ground.

FROM HOFFMANN TO THE BIG SCREEN [20]

We hypothesized at the beginning a decisive influence of Hoffmann on the cinema of Roman Polanski: if in fact one compares the salient motifs of "The Sandman" with some of the obsessions of the Polish director (especially The tenant on the third floor, with all references to the theme of the "double" and the disintegration of the ego; but think also of Repulsion and, for other more witch-themed stories, which we will analyze in the second part of this study, the classic Rosemary's Baby) you will not be able to help but agree with us. The sensations experienced and the suggestions suffered by Nataniele in Der sandmann the Polanskian protagonist wonderfully follows ultimate, especially as regards the so-called “apartment trilogy”, in which the themes of doppelganger, of the "uncanny", of the "puppet" character of man and of Weird understood as an implacable and inevitable destiny:

“He [Nataniel] would sink into gloomy reveries and soon appeared as strange as he had ever been seen. Everything, his whole life had become a dream and a premonition; and he kept saying that every man, while believing himself free, was enslaved to the cruel game of dark powers against which it was vain to rebel, while instead he had to humbly resign himself to his own destiny » [21]

And certainly not less this and other Hoffmannian “Nocturnes” have inspired David Lynch [22]: the structure a Moebius strip of his films, the various doppelganger existing in independent yet interconnected space-time segments, the casual recourse to the "uncanny" in all its possible and imaginable branches are what comes closest to the visionary Hoffmann in the context of the "seventh art". Keep in mind what has been said about this labyrinthine tale which is the emblem of Hoffmann's poetics and compare it, for example, with the oneiric paroxysms of Lost Highways o Mulholland Drive, film in which different characters, played by the same actors, represent distinct fractions of the same person in different space-time lines, or more prosaically - and Freudianly - different personality in conflict living together within the same person:

“Then perhaps, dear reader, you will be convinced that there is nothing stranger and crazier than real life and that, after all, the poet can grasp life only as a pale reflection of an opaque mirror. "[23]

IN THE PART TWO WE WILL CONTINUE THE ANALYSIS STARTED HERE, FOCUSING ON OTHER "NIGHT STORIES" BY ETA HOFFMANN

Note:

[1] FREUD, Sigmund: The uncannyin Essays on art, literature and language; Bollati Boringhieri, Turin 1991

[2] The writer was able to consult the edition The man of the sand and other tales, Rizzoli, Milan 1950

[3] FREUD, op. cit., p. 171

[4] Ibid, pp. 174-175

[5] Ibid, p. 176

[6] See MACULOTTI, Marco, Arthur Machen and the awakening of the Great God Pan, on AXIS mundi.

[7] EIGHT, Rudolf: The Sacred; SE 2009

[8] LIGOTTI, Thomas: Nocturnal; the Assayer, Milan 2017; pp. 11-12

[9] JENTSCH, Ernst: On the psychology of the uncanny, 1906

[10] LIGOTTI, Thomas: The conspiracy against the human race; the Assayer, Milan 2016; p. 79

[11] Ibid, pp. 80-81

[12] There is a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, Ole Lukøye (in Italian "Ole Chiudigliocchi", 1841), from the name of the fairy-tale character who helps children sleep, sprinkling a little milk into their eyes with his magic syringe. In the Danish author's fairy tale it is a positive character: the “Sandy Wizard” of Hoffmann's story has, on the other hand, a much more sinister connotation.

[13] HOFFMANN, ETA: “The man of the sand”, in The man of the sand and other tales; Rizzoli, Milan 1950; p. 18

[14] Ibid, p. 19

[15] Freud notes that in Italian Coppola is equivalent to the "crucible" on which N.'s father and Coppelius carried out their magical operations, and Coppo stands for "eye cavity" (FREUD, op. cit., p. 282, note 1). Consider our choice to highlight in italics, given the high symbolic value, the respective professions: the mechanical it has to do with mechanisms, with the function of repairing worn or broken devices; the optician, of course, with the eye and sight, archetypal themes prevalent in Hoffmann's poetics and particularly in the story analyzed here.

[16] HOFFMANN, ETA, op. cit., p. 39

[17] Ibid, p. 43

[18] Ibidem

[19] Ibid, pp. 46-47

[20] We point out to the reader that a film version of Der sandmann it was shot by Giulio These: it is the namesake The sand man, first episode of the cycle The devil's games. Fantastic stories of the nineteenth century broadcast by Rai in 1981.

[21] HOFFMANN, ETA, op. cit., p. 29. It should be added that in another story by Hoffmann (Fragment of the life of three friends) we are talking about a young man who, having moved to the house of his deceased aunt, begins to be "possessed" by her spirit, a narrative device disturbing extremely similar to that used by Polanski ne The tenant.

[22] On Lynch, cf. MACULOTTI, Marco: The secrets of Twin Peaks: the "Evil that comes from the woods"; on AXIS mundi

[23] HOFFMANN, ETA, op. cit., p. 27

Congratulations on the very interesting article, discovering this text prompted me to want to read it absolutely.

I did a research and I noticed that various editions have come out over the years, can you advise me which of these you consider the best?

rizzoli 1950

bur 1982

blacksmiths 1997

translations can sometimes cripple a great book and I would like to avoid this inconvenience.

Thanks in advance

Ad maiora

Hi Dario, and thanks for your interest! I am very happy to answer you. I have the Rizzoli edition of 1950 and the translation is good, but it is a little book that being 70 years old is very difficult to find in good condition. I suggest you buy the "Nocturnal Tales" (Einaudi 1994, then reprinted in 2017) in which you find both "The Sandman" and the other tales of 1816-17 (which we analyzed in the second part of the article - with the 'exception of "Vampirism" which is separate). I know that the Notturni have recently been reprinted also by L'Orma in a beautiful edition of the “Hoffmanniana” series, however if I do not own it I cannot guarantee the translation.

A salute.

MM

Thanks, I'll take the 1994 Einaudi edition, since I'm also interested in the other stories.