An exhaustive discussion on the way in which, through the centuries and cultural traditions, the act of ritual suicide has been considered and lived.

di Robert Eusebius

image: Jacques-Louis David, “The death of Socrates”, 1787

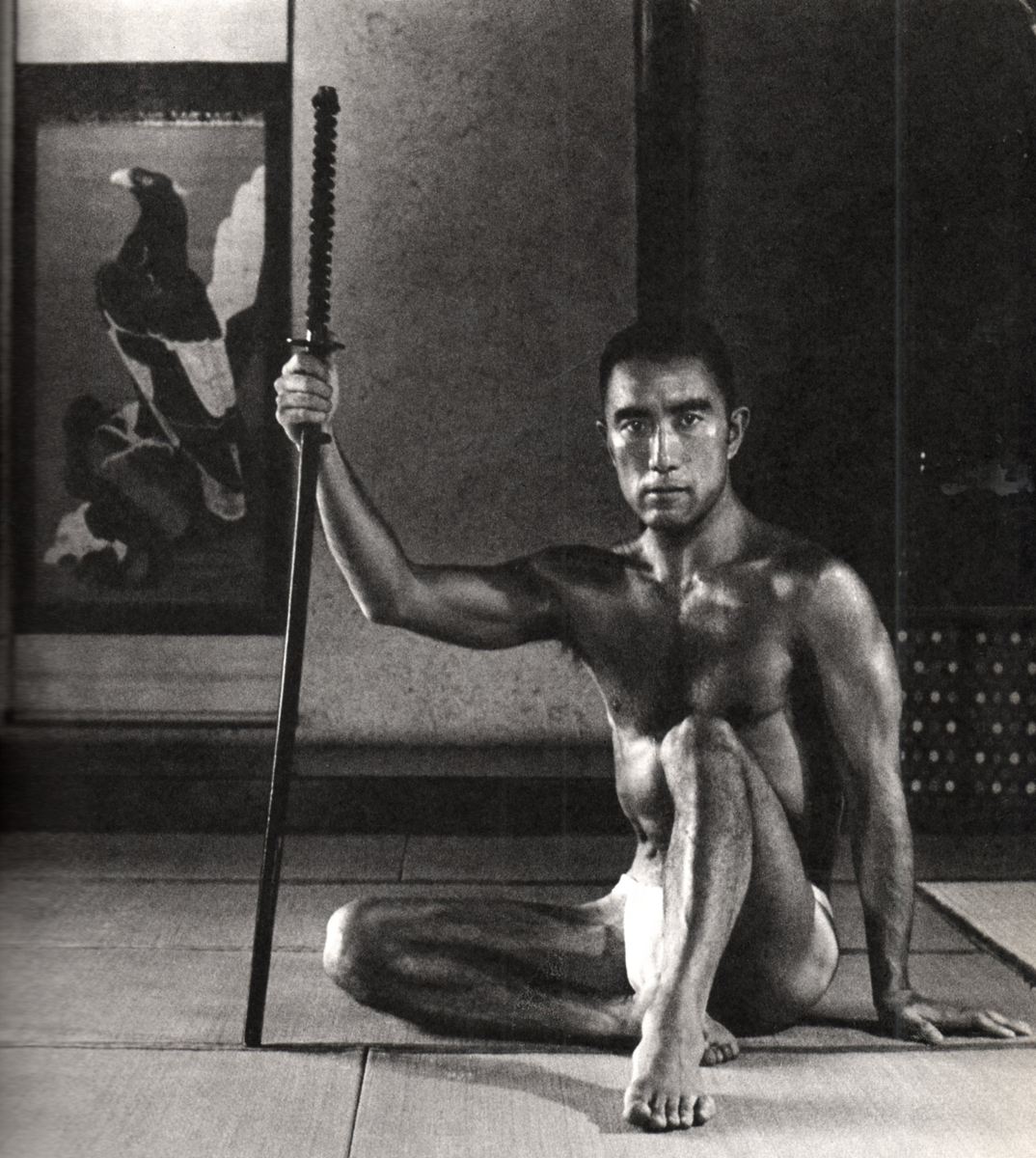

On November 25, 1970, the writer, three times nominated to the Nobel Prize for Literature, Kimitake Hiraoka, better known as Yukio Mishima, commits suicide at the age of 45. That day, Mishima after introducing himself and having occupied, along with the four most trusted members of the Tate no Kai [1], General Mashita's office in the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japanese Self-Defense Army, harangues from the balcony of the office a thousand men of the infantry regiment in the presence of journalists and televisions. Mishima's idea was to start a coup but his intent failed, only getting to irritate the crowd that mocked and mocked him. He later performs the last act of his life committing suicide with the Seppuku rite [2], according to the Bushido rules [3] Samurai code of honor.

What Mishima publicly put into practice was not the desperate and last gesture of a misfit but the extreme appearance of a ritual that is still today in the memory of an epic of honor deeply inherent in the customs and soul of the Japanese people. . An act that, inconceivable to the Western mind, grew in the deep and wounded womb of the spirit of Mishima, fueled by a nationalism bordering on sacredness due to the deep attachment to the traditional roots of Japan and to its representative: the emperor. That act was the dramatic evolution of an inner fire between honors and rituals, between stereotypes and myths, between contempt and obedience, between passion and tragedy, between theater and reality. The words of him shouted to the crowd gathered under the palace, on that November 25th of 70, are an example of that spiritual feeling and testament [4].

"We must die to restore Japan to its true face!" Is it good to have life so dear as to let the spirit die? What army is this that has no nobler values than life? Now we will testify the existence of a higher value than attachment to life. This value is not freedom! It is not democracy! It's Japan! It is Japan, the country of history and traditions that we love. "

It was the gesture of an exceptional, sensitive man, deeply tied to the tradition of his country; the last of the Samurai. It was an act of protest and demonstration that was erroneously labeled as a deranged idealist; one cannot understand Mishima's mentality if one does not know his entire intellectual and vital path, his writings, the concept he had of an integral man, his traditional, metaphysical formation.

At this point and before entering into the merits of the article it seems right to give some explanations to those who read us. The topic, in fact, lent itself to various interpretative cuts and insights: some of these could have offended the sensitivity of some readers and for this reason we were fought in publishing it. We have resolved this perplexity with the choice of the address that we have decided to give it, an address that goes beyond the sentimental aspect and from any psychological, ethical or moral implication. Don't be bothered if, however, the subject may in some way disturb someone's soul. In an essay you face the act of suicide as last resorteven if of the sacred and ritual aspect, the cold treatment of such a definitive aspect should not appear offensive, nor the narrow boundaries that we had to impose on ourselves in the economy of this writing. Having said that, we are aware of how the current world economic situation leads, dramatically and in ever greater numbers, some men to a choice with no return which, this one, grows and evolves on the terrain of despair and impotence or the lack of any opportunity to assert their rights of honor and dignity [5].

On the contrary, we do not agree that suicide, as it has been cataloged, is always an act of self-harm that develops on a terrain of serious discomfort or mental illness. We explain ourselves better. We are firmly convinced that some of these events do not have, in the most absolute way, this substratum, even if we are aware that such a statement could make many turn up their noses. In Western society, ritual suicide is no longer conceived as a sacred and honorable act [6]. The idea of life, particularly expressed by religious interpretation, has assumed the value of intangibility in Christian ethics since it was understood as the expression of a divine act and as such should also remain the event of death. [7]. In this regard, the Church believes that this extreme choice is a profanation of the body intended as a temple of the spirit. Life is the essence of God, so suicide would represent an act of abandonment and loss of the transcendent hope of salvation [8] and, as such, to be abhorred and punished as a grave mortal sin.

The Old Testament equates death to the loss of the Paradise home due to Adam and Eve's disobedience to God (Gen. 2-3). According to this exegesis, the death pursued would be the confirmation and reiteration of the sin of pride through disobedience in opposition to the divine will and as such infernal and Luciferian. [9]. This interpretation applied to sacrifice through ritual suicide appears to us an inconsistency in the light of the immolation of all the Christian martyrs they have suffered voluntarily for their creed. Instead, we think that the sacrifice of one and the other is superimposable since the idea was generated in both cases by a principle of superior spiritual coherence and not by an idea of self-harm; suicide, beyond the state of desperation, despite all its inherent drama, is instead to be considered the last act of virile honor of a man and as such, absolutely to be respected and understood. And it is evident that there is a deep gap between the case of Mishima (as well as any other case of ritual suicide) and those that less spectacularly have occurred and continue to happen. We do not forget them nor do we allow ourselves to criticize them because we think we deeply understand the inconveniences that have caused them.

However, this is not what we want to talk about. In this essay we will try to consider not the pure act itself, but what has traditionally meant the deliberate sacrifice, the voluntary and conscious immolation of one's life on the altar of free will through the sacred and solemn recognition of the right to death. From a historical point of view, the first examples are lost in the mists of time, inextricably linked to legends and sagas. From which it must be deduced that this act, falling within the symbolism of the myth, is somehow distinguished by an Olympic and noble characteristic and this remained even when men replaced the mythical lineage of heroes. This inference finds its roots and its sufficient reason in the concept that life, coming from the gods, had to be lived honorably and for the glory of them. An idea shared in the mystery-initiatory ways and in the speculations of some philosophical schools. When life no longer allowed to be lived to the glory and honor of the gods but it was only pain and pain or simply anonymous life, death, sought in battle or through improbable enterprise, covered the superior and noble sense of contempt for danger and overcoming. fear of death, manly forcing one's being towards liberation from human bonds, thereby leaving one's name to posterity and becoming godlike.

Seneca, philosopher of the Stoic current, in his own Epistolae ad Lucilium reflecting on suicide he hoped that the philosopher, but not only him, had to prepare to die at any moment by preparing to leave this life without regrets. For Seneca, death was the ineluctable point of arrival of every life but also the result, we will add, of the responsibility for what we carry around and what we have been able to grasp, not only from a material point of view but more specifically. of our spiritual becoming as it represents the ultimate goal and the synthesis of all the small deaths of our individuality, whether intentional or accidental, that we undergo in the course of our life.

The Ancient Hero [10], the hero par excellence was the one who, conscious of his sacrifice, which he knew was extreme, performed a generous act of courage for the good of all, accepting death as the noblest and most beautiful action. For this he went to meet the kalòs thanatos, that is to the "beautiful death" since the last act of one's life was to be epic and forever remembered as a heroic legendary model. The characteristic, the sign, the enterprise of the hero in the myth is given by the objective and the will of his own immolation and this will was the real weapon of the sacrifice that led the hero to confront his own death in overcoming his own human limits, accepting it according to principles of universal spirituality above and beyond oneself.

In the Hindu tradition, the Vedas clearly report how the sacrificial victim had a double value in which the victim and the priest coincide and merge at the same time with the altar, the smoke, the invocation, the whole world that surrounds it. The very primordial creation of the world, in all traditions, begins with a sacrificial act [11]

« consequently the final purpose of the sacrifice is not only to continue the creative operation begun "once" from the beheading but also to overturn it with the total reconstitution of the divided divinity, and with that of the sacrificer himself, identified with the divinity and with the sacrifice. »

With these assumptions it is reasonable to think that the beginning of that day will see the dawn of "a good day to die". There will be no others, that will be the last and therefore deserves to live it in full consciousness. It was decided by the God who dominates him and who pushes him to find, through himself, balance and to return, like the exile, to his spiritual homeland. The conscious and voluntary sacrifice, symbolically represented in the initiatory paths, has its own ontological meaning where the result of this act will be the liberation from human limits that will launch the initiate towards the higher states, which in the classical era was expressed by saying that it would be become like a God. An example is the myth of Hercules with the story of his exploits in expiation of his murderous madness. The story, which must be read in a symbolic perspective, represents the path of the hero who will take him to the pyre that he will raise on Mount Eta and who will transform him into immortal [12].

Heroic suicide is the choice, certainly questionable, of an extreme confrontation with oneself, with one's fears and overcoming them through the crossing of the symbolic door of life and beyond the mysterious guardians of the threshold. It is the act that brings with it the conscious search for the cancellation of one's own illusion and, consequently, of the world and its veils (maya) in which being struggles. After all, on closer inspection it is the superior meaning of all the initiatory paths. In this sense, and with the due distinctions, we can read one of the most interesting symbolisms of the Eastern and Far Eastern World which is represented by the countless demonic and fantastic masks that adorn the portals of the temples. We refer to the kala-mukha Hindu and T'ao-t'ie Chinese. Particularly horrifying and polyform, these masks are identified as the Destroyer, the swallower but at the same time in addition to terror, they represent the hiatus, the door that, bravely crossed, gives eternal life understood as a spiritual rebirth. [13].

It is therefore through this idea that the masks, a horrifying manifestation of death, show us how the spiritual path, at a higher level, is represented by the symbolic death to the world and its possible extreme application: suicide, where beyond the caesura the terrifying mask is transformed into the glorious image of God (being two aspects of the same hypostasis). In the Japanese Zen doctrine, to which the Samurai adhered, death and life were considered on the same level since death and birth would only be the two faces of the same door.

The warrior's constant search for inner balance allowed complete detachment from emotions as long as he was able to maintain a cold determination in combat. The fencing master Miyamoto Musashi in the XNUMXth century wrote:

« Under the raised high sword, there is hell that makes you tremble; but go on, and find the land of bliss »

If therefore this was the constant of the way, even the extreme act such as suicide could not be a reason for hesitation and fear. There Buddhist doctrine it states what are the salient points of "perceptual reality" that come from the teaching of the Buddha himself. They are:

- The doctrine of suffering, Dukkha, that is the concept that all aggregates (physical or mental) are the cause of suffering if you want to keep them; they cease when one wants to part with it.

- The doctrine of impermanence, Anitya, that is the concept that everything, including the physical body, is composed of aggregates (physical or mental) therefore subject to decay and extinction with the decay and extinction of the aggregates that support it;

- The doctrine of absence, Anatta, of an eternal and immutable individuality or the ego, the so-called doctrine of Anātman, as a consequence of a reflection on the two previous points, the result of which will be the search for the way to extinction [14].

Ritual suicide was therefore contemplated in the religious doctrine of Zen Buddhism through the acceptance of extinction and was pursued as a sacred act. and done in the name of and for the Principle; as such, albeit with some variations, it was the patrimony of different cultures. In truth, in the consideration of its boundaries between lawful and illegal in the ancient world there will historically be no clear-cut position, so much so that in ancient Greece there will be two schools of thought, one contrary to the other, which nevertheless coexisted. From which we can think that the distinction between the different conceptions of suicide that were made at the time was the same that we have tried to make evident here between the hero and the gens, between the'and put and discouragement, by amending this act of infamous and criminal features. On the other hand, among the various civilizations stand out, with a legendary symbolic meaning, those traditions whose steps of the relative Olympians were lapped by suicide.

In the Nordic tradition it is the god Wotan himself who welcomed those who had sacrificed themselves in battle and suicides into Walhalla. For those close to the god, achieving victory, dying gloriously in battle, or sacrificing oneself were equally desirable. Indeed, Odin welcomed them as his favorite adopted sons, they were the chosen ones and the guests to the eternal banquet he presided over. On the other hand, Odin was called the god of the hanged in memory of the mythical tale that saw the sacrifice of him by the effect of the rope in order to obtain, after the sacrificial test, the science of the runes, that is the possibility of prediction and knowledge.

In the culture and law of ancient Rome as well as that of Greece [15] suicide was the highest expression of the personal freedom of the citizen and therefore was not forbidden nor was it considered dishonorable when this was granted by the senate and was assisted by a particular court. For the civilians Roman was a choice that involved only and only his person. The state and its laws could not violate the private sphere when this did not harm society in general or more particularly the interests of others, indeed it was celebrated in some cases as act of courage and heroics virtus inscription.

In the land of Egypt, where Anubis and Osiris were, in the pharaonic period, the guardians of the beyond the tomb, suicide represented the expedient to avoid a dishonorable death. The priests granted the culprit of noble rank the possibility of avoiding an ignominious end, for example the death of Queen Cleopatra who escaped Octavian's humiliating imprisonment by committing suicide: getting bitten by the asp, symbol of the sacred gold that was worn on the headdress of the pharaohs and consecrated to the goddess Uadjet, divinizing her person who thus ascended to the Egyptian Pantheon. The celebration of death and its hierophany in the traditional thought of ancient Egypt were a recurring and daily motif, as evidenced by the numerous burials for the entourage of the Pharaoh whose death was practiced voluntary mass suicide [16] at the end of following and serving their king even in the afterlife [17]. The remains of these were buried, as a maximum honor and respect, together with the pharaoh himself or in neighboring tombs.

The exaltation of suicide in ancient Egypt, as for other traditional forms, for some scholars seems to be veiled by a sort of romantic and sentimental vision as an act of extreme fidelity, implying a sort of sinister beauty and voluptuousness. We do not share this interpretation, which we think is a more psychological - sentimental than real reworking. On the other hand, it seems to us that we must probably take into consideration the rites related to the mysteries of Osiris and his post-mortem regeneration as a spiritual rebirth. It is a question here of a symbolic concept which in the initiatory world refers to the overcoming of the world of forms. This idea is present, as we have seen, in all traditions starting from prehistory through what will be called the initiatory caves linked to the Mother Goddess and to all those paths that initiatedly referred to the regeneration of being.

In Freemasonry itself the container that is locked up in the cabinet of reflection symbolically undergoes a psychic regeneration and a purification through a prefigured voluntary death in which it should leave the mortal remains. The place, which represents a sort of tomb, is the virtual experience of the alchemical putrefaction of matter where among the corpse remains calcined by the sacrificial fire he will have to find, among the ashes of individuality, theoccultum lapidem, the shining gem that will light up the darkness of the profane night which will trigger the regeneration process and lead it to shine the light of the midnight sun in the initiate [18]. The same compilation of the will reminds the recipient of the last act of his profane life and the promise of a new life. On the other hand, it is a legend of Freemasonry, strongly impregnated with symbolic elements, the story of the suicide of the architect builder of cathedrals who, at the completion of his masterpiece, would commit suicide by throwing himself from the eye of the dome [19].

At the Mayan civilization, Ixtab (The Lady of the Rope), was the patron goddess of those who took their own lives; the goddess accompanied them to a paradise as they were considered sacred because they had chosen what was beyond life. Her image was represented hanging from a halter and in a state of partial putrefaction; on the other hand the Maya raised to particular importance suicide by hanging which was considered a means of accessing celestial otherness in what they considered their paradise.

In researching and deepening the traditional aspects, in ancient civilizations, of the end of life, there is always not only a sort of virile acceptance but the absence of fear of losing one's individuality with the certainty that one's life (with all the metaphysical distinctions regarding the different theories of evolution post-mortem) continued in one of the different manifestation plans [20]. Nothing could be further from what has been imposed for several centuries in the West in which death is conceived as a pitifully painful phenomenon despite the fact that religion ensures the salvation and survival of the soul (this passage is called, in the Byzantine liturgy, in the hymns of San Giovanni Damasceno, a "terrible mystery"). It is clear that since death is seen as a painful and bitter passage, it implies that every aspect of this is repressed and considered negative. However, as it may seem a contradiction, committing suicide is not a surrender as much as not wanting to bow to the inevitable fate and the contrary events, avoiding, through an honorable death, the dark shadow not only of dishonor and cowardice but in particular of the ephemeral contingent existence.

The suicide will concede nothing to the silence of cowardice and cowardice and it will be with his own oblation that he will be able to amend himself and, in this way, to exit the cycle of forms by sacrificing himself on the altar of honor metaphorically shouting his own courage without retreating on the ground of life. How the warrior in combat will overcome his worst opponent, his own individuality. We are not dealing here only with an abstract concept: it must be considered (from a perspective of spiritual maturation) as an aspect of symbolic battle as it actually is, even if on closer inspection this duel is much more real than what is believed and actually fought. on inner ground against one's fear of death.

It is still the oriental texts, those that refer to the Japanese art of fighting, to return to the opening theme, that help us in this philosophy. In the art of the samurai sword the masters taught that, to survive, one must die; to live well it was necessary to draw the line that ends with death. For the Samurai, according to the Bushido code (and towards a spiritual realization) it was necessary that he live without clinging to life, suppressing the desire to live. Paradoxically, attachment to life makes you die, and the abandonment of life makes you live [21].

From a metaphysical point of view, the sacrificial oblation is the act that necessarily determines the transformation and the passing beyond. It is comparable to the symbolism of the snake that sheds its skin for a new season of life, while the ancient agricultural civilizations recognized in the symbolism linked to the pressing and transformation of grapes the sacrifice of the fruit necessary to renew itself in the drink of immortality or in the grinding of wheat. through the bread making which in the Christian tradition are transubstantiated into the blood and body of the Savior.

For what it concerns sacrifice as an oblation of oneself, we cannot forget the custom for the West, with the army in ancient Rome, according to which the commander voluntarily sacrificed himself to the Mani gods: in case of danger of defeat, for the salvation and the victory of his men he sacrificed his own life [22]. Another example is given by strict rule of the Templars, in which Saint Bernard wrote that the Templar "it kills quietly and more quietly dies». They were required to fight to the extreme sacrifice and could not retreat in any way in the face of the enemies, nor were they authorized to redeem themselves or ask for mercy from the enemy if they were captured. They always and proudly claimed the privilege of the front line in battle; death promised and accepted without regret in defense and glory of God.

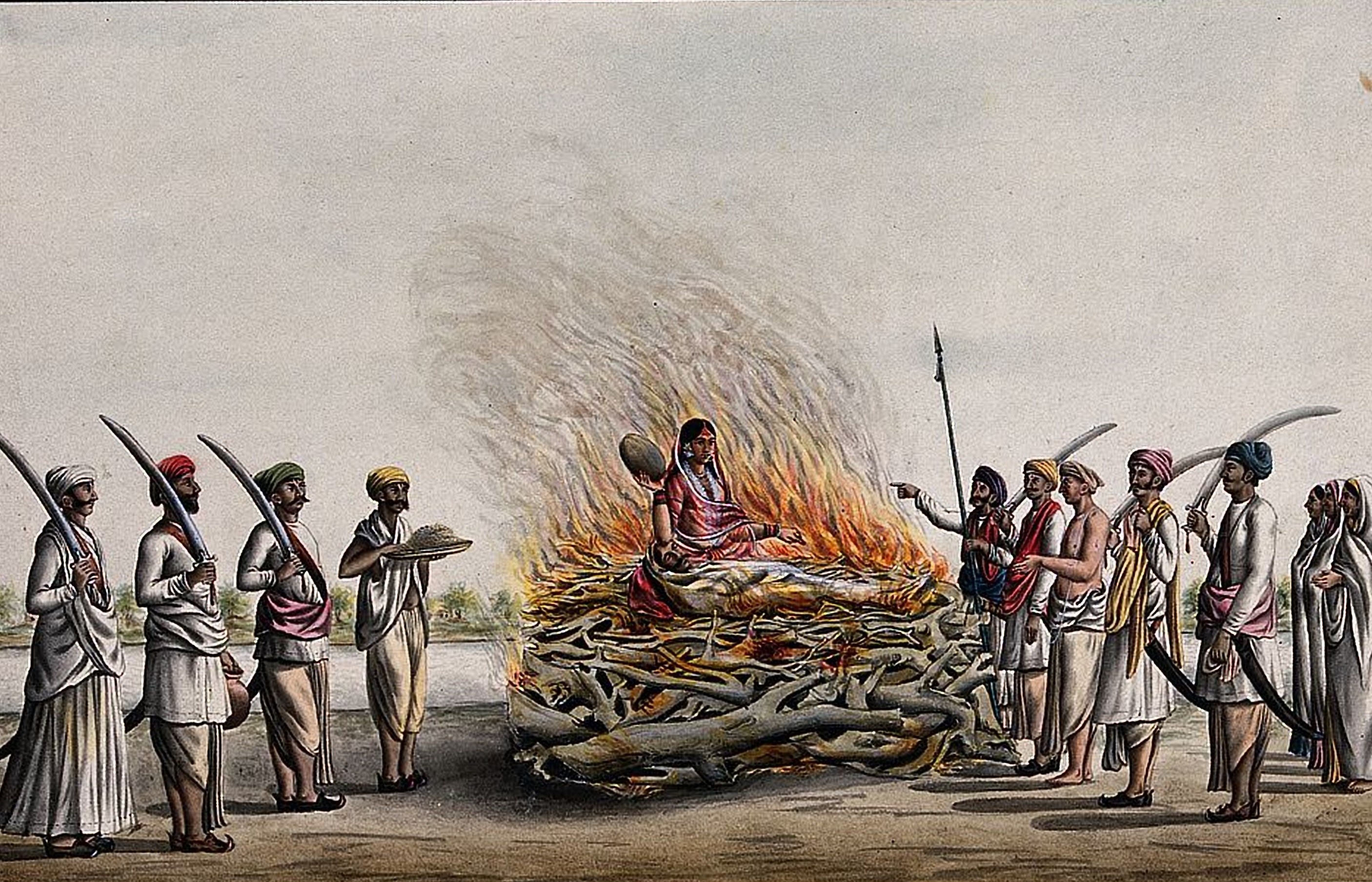

Different consideration must have the practice that was carried out among the Hindus and that we do not feel like sharing even in an abstract way; however in this article it certainly has a significance not only of an ethnological historical order. This is the custom called Satī or Sahagamana (the joint departure, now prohibited and criminally prosecuted even if this practice still occurs sporadically). This custom in ancient times concerned married women who remained in a state of widowhood who sacrificed themselves on the pyre of their husbands most of the time with the complicity of relatives. Practice that took hold in India in medieval times among the highest castes: those of priests and soldiers.

In truth, the custom of the Sahagamana derives from the traditional tale, present in the Puranas, of the goddess Satī, Shiva's wife and Shakti. The myth tells how the father Dakśa considered their marriage a family dishonor, this attitude angered Satī who, invoking the yogic powers, sacrificed himself by burning. This myth was traditionally interpreted as the utmost devotion to one's husband considered crucial as a teacher in the social and spiritual journey of women. In truth we have not found in the texts any trace of this barbaric prescription which seems to have some similarity with the sacrifice of all the goods of the deceased pharaoh including his wives. The reference is that of mass suicide of the Pharaoh's entourage but, if in this case the suicide was voluntary, in the Hindu tribal society the Sahagamana, more often than not, was imposed.

It is true that this once voluntary practice has over time been strongly misrepresented among the less affluent castes, finding support on the idea of the supposed inferiority of women and their inability, in a state of widowhood, to maintain themselves in society, reason and excuse for avoiding support of the widows by the groom's family. However, the Indian Middle Ages tells us how many sacrifices, in a period of war, were frequent among women of noble rank who in this way escaped from a condition, wherever it happened, of prisoners or slaves, sacrificing themselves with their children. according to it far, thus safeguarding the honor of husbands and their brothers. Even today there are bas-reliefs in which many small hands are carved on the walls, in some fortresses of Rajasthan. Each hand represents a woman who threw herself into the flames of the sacrificial pyre, and is all that remains in memory of those proud and unknown women. The fact is that those women who voluntarily submitted themselves to the ritual of Satī today they are remembered and honored with temples built in the place of their suicide and prayers and ceremonies are addressed to them.

At this point we would not like to appear as the epigones of suicide. It is obvious that we do not shy away from understanding humanly and sentimentally the family consequences of those who commit suicide: the stigma, the violent and traumatic despair of relatives, the painful and unexpected abandonment of life. However, at the beginning of this paper we clearly stated that we impose ourselves, as far as possible, a remain within the confines of the rational and the sacred aspects of suicide without conceding anything to the sentimental and that is what we will try to continue doing.

On the other hand, ritual suicide has never rooted its roots in the regions of sentiment, it has never fed on existential depression and has conceded nothing to self-harm, indeed this act must have had a strong determination and a lucid and conscious rationality. Therefore one's freedom, conceived as becoming metaphysical and as the highest aspiration of being, cannot and must not be conditioned or limited by individual sentiment, much less by those around us. On the other hand, if the Eastern doctrines, but not only them, consider individuality, an illusion from a metaphysical point of view, we do not understand how those who aspire to infinity should forcefully worry about the finished.

However, this can be completely understandable for those who, having not developed the perception of the infinite and of their own becoming, feed a sort of despair of the finite and therefore of the end of their life with the consequence of having a horror of suicide. On this aspect the thought of the Scottish philosopher and historian is interesting David Hume (Edinburgh, April 26, 1711 - Edinburgh, August 25, 1776). Born and raised under the enlightenment of the eighteenth century, despite his radical concept of the mechanism of human nature and its becoming, he remains the greatest theorist of liberalism. His ideas on the lawfulness of suicide, although limited from the metaphysical point of view, grant man the free will of a decision that is and must remain in any case in the possibility man.

The philosopher's thought questions divine providence and omnipotence. Summarizing his thought, he goes so far as to say that, if our life is actually sacred and consecrated to God, suicide would be prevented by the action of divine providence. Because if providence guides all these causes, and nothing happens in the universe without its consent, neither does the death of the individual, however voluntary, happen without it. Therefore (Works, Laterza, Bari 1971, vol. II, p. 989, p. 990)

« Qhen the repugnance to pain prevails over the love of life, when a voluntary act anticipates the effects of blind causes, this is only a consequence of the powers and principles that the almighty has placed in his creatures. »

and, further on,

« Qhen the pains and pains overwhelm my patience to the point of making me weary of life, I can conclude that I am called back from the place where I was placed»

From this it follows that in the moral and social sphere the possibility of being able to restore to men the power over their lives and the freedom to escape must be strongly affirmed, last resort, not only to physical suffering and decay but more properly to metaphysical malaise.

For oriental doctrines with a naturally metaphysical vision (but above all not impregnated with sentimental moralism) there can be no divine punishment for one's sacrifice but rather the supreme act would represent the maximum aspiration and will to reunite with one's God. [23]. Just as the exile yearns for his return to his homeland, so the being who has overcome the attachment to life can only aspire to rejoin the Principle from which his journey began. And it is not certain that that reunion, achieved through a harmful act, is enough not to want to be part of this world anymore.

Arrived at the end, we are aware that we have just scratched the subject, but what has been said here, even in its conciseness, may help to give a more rational and less deplorable vision of suicide. Someone will be able to point out the absence of treatment of two aspects concerning the Kamikaze of the Second World War and the Shaids of Islamic Jihad. It was a deliberate choice because we do not consider these actions as voluntary choices but induced by psychological plagiarism or under the influence of drugs, aimed at intentionally pouring out their deadly terrorist action on defenseless people.

In the Hagakure books [24] the words are shown (collected by the student Tashiro Tsuramoto) of the former Samurai monk Yamamoto Tsunetomo, which for us Westerners may seem disturbing, but which shows everything the abysmal metaphysical caesura between Western sentiment and Eastern rationality whose synthesis is all in the following sentence:

« I have discovered that the Way of the samurai is to die. Faced with the alternative of life and death, it is preferable to choose death. »

The human being is but the envelope of the spirit and, as with anything, the container is not as important as the content.

Note:

[1] The paramilitary Tate No Kai (Shield Association) was founded by Mishima himself who gathered around fifty young traditionalist conservatives. The biographers asserted that this training was founded to try to hide his father's literary interests, which he considered "a sissy business." This theory, also influenced by his right-wing political militancy, in our opinion only served to belittle the figure of Mishima. Despite being a controversial personality who had conflicting relationships with the same people around him, this attitude was inspired by the philosophy of the Bushido code of the Samurai whose life was not only dedicated to the art of weapons but to the search for his own spirituality through the Zen Buddhism and Taoism as well as cultural deepening through the composition of refined poems, painting, literature and patronage.

[2] Seppuku is translated as "cut of the stomach". In the West it is commonly known as Harakiri but the terminology is not exact and it is fundamentally a misunderstanding. In fact, there are some differences: Seppuku is the rite of cutting the stomach, while Harakiri is the cutting of the belly but what makes the two suicide techniques more different is the cutting of the head (performed by a friend, the kaishakunin, character particularly gifted in handling the sword) present in the Seppuku which in the Harakiri is completely absent.

[3] Bushido literally means "Way of the warrior" and represented for the Samurai the rule of conduct based on honor both in battle and in social life. More properly for the Samurai the Bushido represented the law that regulated his spiritual path according to the Zen doctrine. From an early age, the future Samurai had grown up in order to control his emotions through hours and hours of Zen concentration exercises to increase self-control so as not to betray emotions or fear of any kind, thus bending his sentimentality to a calculated reasoning. Even today in Japanese society, Bushido represents for some men a core of strictly followed ethical principles and essential behaviors.

[4] In truth, the book is to be considered as a spiritual testament The way of the samurai, a work published by Mishima in 1967 as a commentary on the eleven books collected under the title of Hagakure kikigaki (Notes on things heard in the shade of the leaves) of the Samurai, who became a Buddhist monk, Yamamoto Tsunetomo (11 June 1659, 30 November 1719) the work composed in the form of aphorisms deals with the spirit and code of conduct of the Samurai.

[5] It is estimated that around one million people take their lives every year in the world and the statistics are constantly updated.

[6] In 565 AD for the codex Corpus juris civilis suicide was not considered a reprehensible act of the Byzantine emperor Justinian. The code admitted that it was "justifiable" if provoked by the taedium vitae.

[7] In other respects, in the present there is a kind of repugnance to speak of death as well as of illness with an embarrassing shame. In an efficient, gymnastic and vitalistic society, death or illness is seen as an antisocial event or as a defeat.

[8] The ancient custom of the burial of suicides without funeral, without blessing and done in desecrated land (once it was prescribed "out of town") is still valid today, a prescription that today does not seem to be followed except in completely cases. details.

[9] We would be tempted to ask for evidence, based on the conception of the intangibility of life, of all the deaths and infamous tortures inflicted on men and women perpetrated by the church in the period of the Inquisition without forgetting the persecution and burning of the Templars.

[10] The idea of the classical hero is defined by the Greek terms kalos kai agathos (καλὸMsὶ ἀγαθός = "beautiful and good") this phrase reflected the intrinsic values of the qualities of beauty, of the good, of the noble in which both demigods and exponents of kalokagathia or rather of human perfection. This ideal that combined physical beauty withagathia, that is to the knowledge of principles and values, had a meaning that transcended only the aesthetic and ethical value, being these expressions of spiritual perfection and knowledge.

[11] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, The doctrine of sacrifice. Chapter III Sir Gauvain and the Green Knight; Indra and Namuci. Luni publishing.

[12] There is no doubt that it is a symbolic tale. The twelve labors, a cyclic number that reminds us of the annual cycle but also of the initiatory test, is the age in the boy of the passage from the pubertal period, twelve are the main gods of Olympus. Twelve signs of the zodiac.

[13] Let's not forget the figure of the reptile and by extension that of the dragon that populate fables and legends whose symbolic images, passing from the Greeks and Norse sagas, stretch across the Far East. It is particularly in this tradition that the dragon is often identified with the sensitive soul and with all the cravings and passions that are in us with which each individual must struggle to be the Conqueror in the theological sense. The story in the Gospels of the temptation of Jesus in the desert by Satan represents the battle that must be fought by the initiate against vices and passions. The barren desert itself represents death and is the symbol of the passage beyond. On the symbolism of the kala-mukha Hindu and del T'ao-t'ie Chinese, cf. M. Maculotti, Cyclical time and linear time: Kronos / Shiva, the "Time that devours everything", on AXIS mundi.

[14] In this regard, the countless immolations of Tibetan monks despite having a political substratum, are however in line with the doctrine of Buddhist extinction. Theirs is not an individual act but has a doctrinal and altruistic character, representing the supreme offering of oneself. In the Vyaghri-Jataka, Buddhist canonical text, it is said (by the future Buddha) about self-immolation: "This decision of mine does not arise from ambition, nor from the desire for glory, but only from the will to defeat the evil of the world. I will dispel the darkness of suffering as the sun dispels the darkness of the earth with its light, and all will learn compassion from my example.».

[15] Much of the Roman laws derived from the Greek juridical body and this norm, despite its extraordinary nature, follows the prescriptions of the Greek codes.

[16] Land mummies in the collateral tombs or in the chambers near the royal one indicate that the bodies did not present any trauma but probably their death had occurred voluntarily through a poison.

[17] This particular form of fidelity finds a parallel with the Bushido code and the Seppuku of the Samurai. One of the rules for practicing ritual suicide was the death of one's Daimyô in order to follow him and continue to serve him beyond death.

[18] "Our fathers found the treasure of heaven hidden in the secret cave […] this treasure in the infinite rock" Rig-Veda (I.130.3). In other ways in the Vedic aphorisms it is said that God is buried in us (the divine spark or Sophia of the Gnostics who resides in us). The search and discovery of the hidden treasure of many fairy tales is the metaphor of reaching the divine state.

[19] It is said about the city hall of Brussels (town hall) built in Brabantine Gothic by Jean Bornoy, which Jacob van Tienen and Jan van Ruysbroeck saw the architect's suicide at the end of its construction. Moreover, there are numerous so-called legends about the suicides of architects; among these those that circulate on the “civic” museum in Glasgow, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Scotland or the builder of the Coppedè district, Gino Coppedè, in Rome. Etc.

[20] As far as the Celtic tradition is concerned, Titus Livy, Caesar and Valerius Maximus report in their commentaries, not without admiration, how calmly the barbarians of Gaul or Germany faced and gave themselves to death. Marco Anneo Lucano (Cordova, 3 November 39 - Rome, 30 April 65) in his poem Pharsalia (also known by the title Civil Bellum), tells how the Celts considered death as a moment of interruption on the path of their existence, as a bridge between one manifestation and another. On the other hand, this concept did not concern only men, but was also projected towards animals that were hunted according to particular rituals and honored by the hunter. The Divine Hunt did not represent the end but the sacrifice that gave the animal immortality through the act of bloodshed; this act was comparable to the actual sacrificial act in which sacrificed and sacrificing were one.

[21] We must consider that the warrior way, like that of the Samurai, was an initiatory way applied to the use of weapons (in the Hindu tradition it was represented by the warrior caste or the Kshatrya) whose final purpose was liberation.

[22] This sacrifice was assisted by the Pontifex and the sacrificer pronounced the invocation "Oh Janus, Jupiter, Mars father, Quirinus, Bellona, Lari, Divi Novensili, Gods Indigeti, Gods who have power over us and our enemies, Gods Mani, please, I beg you, I ask you and I promise myself the grace that you grant propitious to the Roman people of the Quirites power and victory, and bring terror, fear and death to the enemies of the Roman people of the Quirites. As I have expressly declared I sacrifice together with me to the Gods Mani and the Earth, for the Republic of the Roman people of the Quirites, for the army for the legions, for the auxiliary militias of the Roman people of the Quirites, the legions and auxiliary militias of enemies»(Tito Livio, Ab Urbe condita libri, VIII, 9).

[23] This concept is in contrast with what is interpreted by the Church which has always considered it an act of pride. Quoting A. Coomaraswamy according to the liturgical texts of the Rig-Veda, the way of sacrifice is the way that leads from lack to fullness, from darkness to light and from death to immortality.

[24] La hagakure it was compiled in eleven volumes in the early 1700s and was not published until 1906. Its author Yamamoto Tsunetomo, who retired to the monastery, will be helped in the collection and transcription by the pupil Tashiro Tsuramoto. L'hagakure represents the code of conduct of the Samurai.

A comment on "Extrema Ratio: notes on "sacred" suicide"