A few notes on the correspondences between the duende, "occult spirit of aching Spain" according to Federico García Lorca, and the Jüngerian "spirit of the earth", with some glimpses of Octavio Paz. In the appendix, a full-bodied extract from the text of the Spanish poet.

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Francisco Goya, "The burial of the sardine"

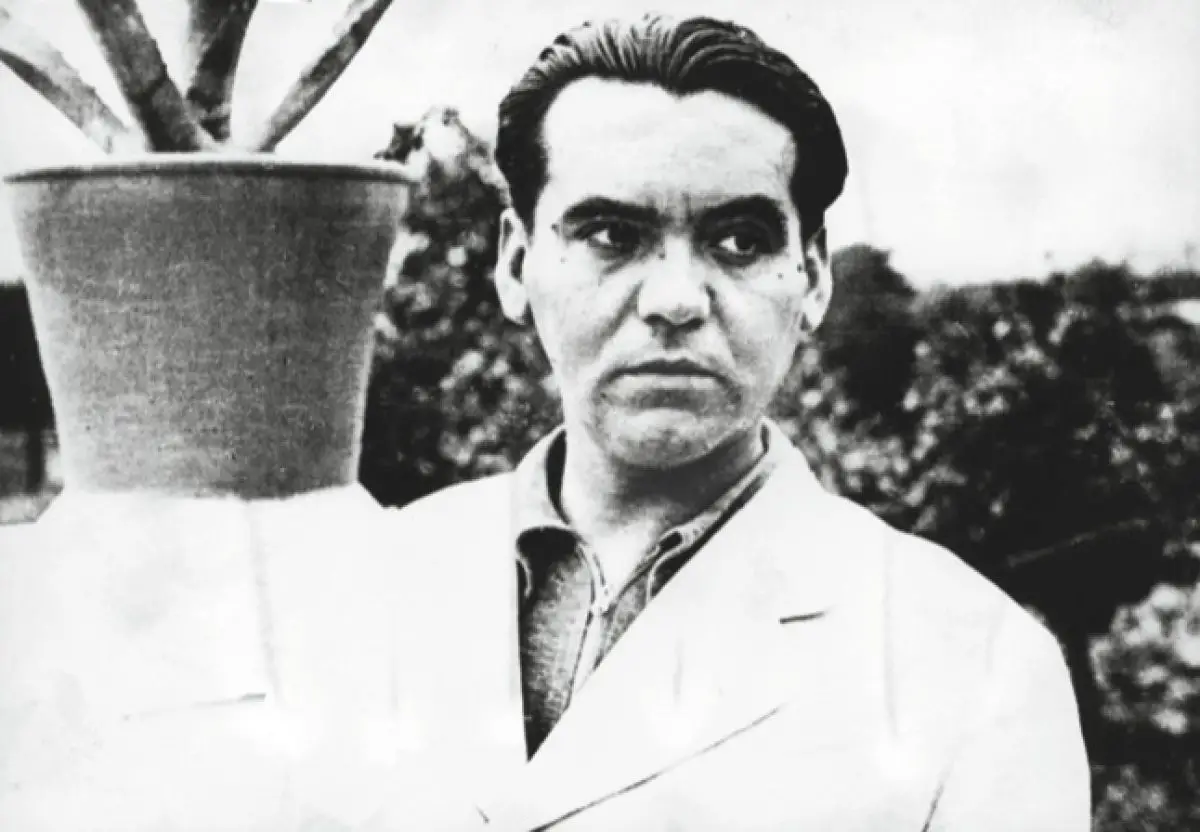

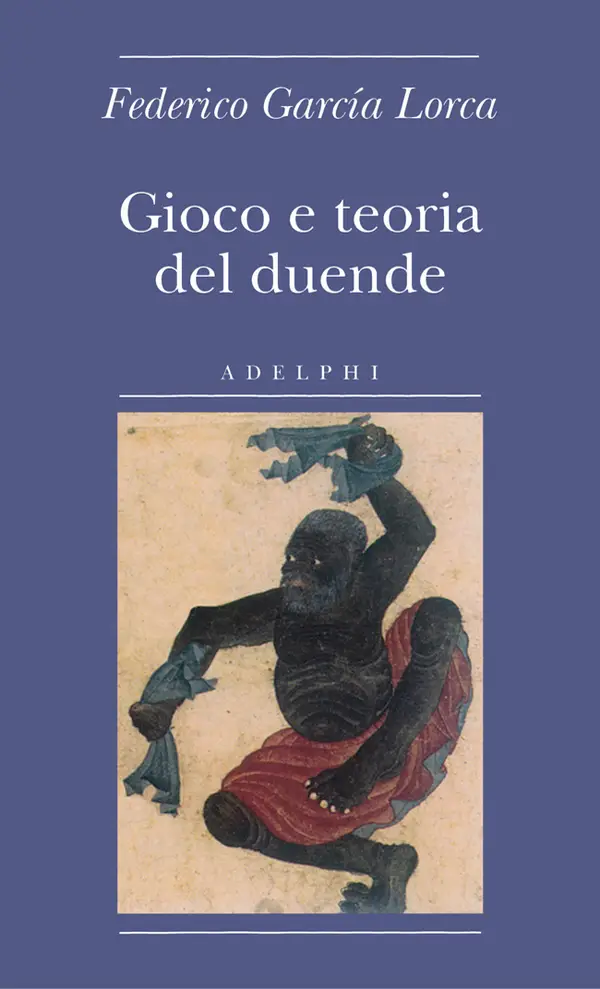

"Game and theory of duende" it was one of four Cuban conferences that just thirty-two years old Federico Garcia Lorca held in 1930. Three years later it was put into prose and printed. By means of this lecture and the consequent transcription for the reading public, the well-known Spanish poet and playwright set out to outline with masterful skill the "occult spirit of aching Spain", going to plumb the darkest ravines, but at the same time more vivifiers of the Hispanic tutelary genius.

A genius who manifests himself in all his dazzling immediacy in pictorial art (Goya), in singing (Pastora Pavón) and in dance, up to the collective rituals of the Spanish soul: the bullfight and, above all, the great "national spectacle" of death, comparable only - notes García Lorca - to that of another country that has been greatly affected by the Hispanic influence, for historical and cultural reasons: Mexico where even today Our Lady is so venerated in her terrifying meaning of Santa Muerte. That Mexico whose dominant archetype in the contemporary era was identified by Octavio Paz in the uprooted figure of pachuco, who "in persecution, draws his authenticity, his true being, his supreme nakedness, pariah, marginalized". That Mexico where:

“The contemplation of horror and even familiarity and satisfaction in dealing with it constitute […] one of the salient features […]. The images of Christ gross of blood of the village churches, the macabre mood, the funeral wakes, the custom of eating bread and sweets made in the shape of bones and skulls on November 2 are habits inherited by natives and Spaniards, inseparable from the our being. Our cult of death is a cult of life, in the same way that love, which is a reputation for life, is a longing for death. »

For its part, the daimon Hispanic, says García Lorca, is to be found in all its varied expressions (Andalusian, gypsy, etc.) in the duende: «Throughout Andalusia - he writes - people constantly talk about duende and he discovers it as soon as he appears with effective instinct ». The meaning of the term is never made explicit by the Author; however, it is known that in the Andalusian dialect duende first of all has the meaning of "Goblin", but it can also be translated as "brocade" or "Fine fabric". In the conceptual duplicity of the term there is therefore on the one hand a dimension so to speak of elevation, of excellence over the norm, and on the other a darker, more panic:

“Anything that has black sounds has duende […] These black sounds are the mystery, the roots that sink into the silt that we all know, that we all ignore, but where does what is substantial in art come from. "

In García Lorca's view, however, the dichotomy of the term harmonizes coherently between its two opposites: only he who has within himself the duende (in the sense panic of the term) can aspire to excellence, to rise above his fellow men, this not depending on his individuality, but rather on having awakened in himself a kind of primal force that, “possessing” the artist (poet, dancer, singer, etc.) leads him beyond his limits, beyond the limits established for the rest of the human consortium. Indeed "the duende it is a power and not an action, it is a struggle and not a thinking "; "it is not a question of faculty, but of authentic living style; that is to say of blood; that is, of very ancient culture, of creation in act ». The duende is, according to the writer, the "spirit of the earth [...] mysterious power that everyone feels and no philosopher explains».

Broadening the view on other geographical shores and other authors, it is to be noted as the concept of "Spirit of the earth" was used thirty years later (equivalent to a perfect revolution of Saturn, ruler of cosmic cycles), by another titan of twentieth-century literature, German Ernst Junger, which in his work At the wall of time (An der Zeitmauer, 1959) gave it the following definition: «an earthly force that cannot be further explained, whose during within the physical world it is given by electricity "[§67], to be imagined" as an animated current that crosses the world and pervades it, without yet being separated from it»[§79].

Even though this “energy current” is impersonal, like García Lorca, Jünger also makes it clear that "The spirit of the earth becomes magical only when it returns", in which "we see it coagulate, crystallize and harden" [§67]: task of man - or, better said, ofdifferentiated individual - is to bring it back to life from what he defines "original background", digging into the depths of one's being: which means in the recesses of one's individuality but also in those of one's genetic inheritance, one's blood, one's motherland. In this way, according to Jünger, the spirit of the earth can return "to men and institutions", so that "cults, works of art, cities can take on a magical character" [§67].

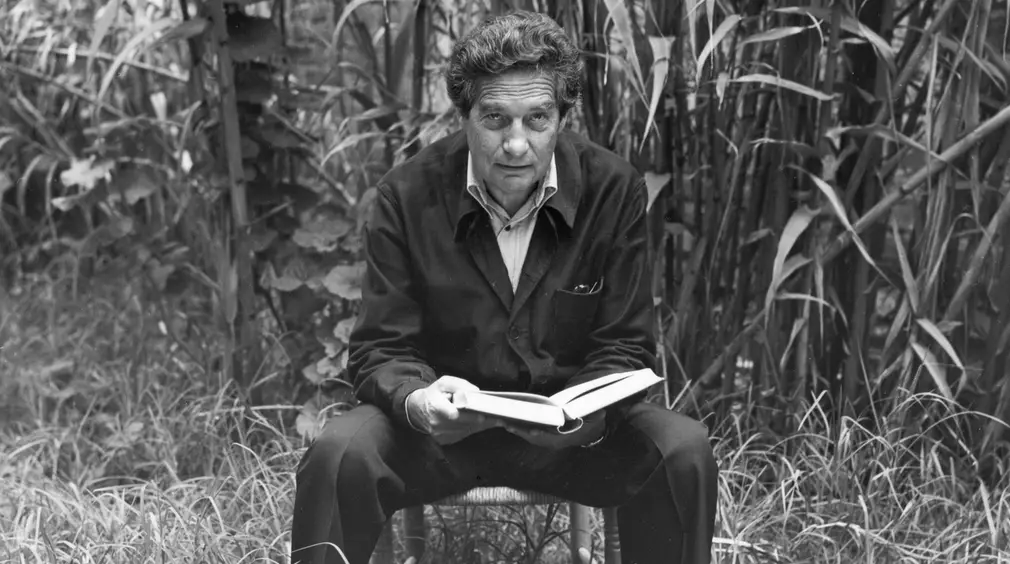

On this we could identify further parallels: for example with james hillman (Essay on Pan, The dream and the underworld, but also The code of the soul, where the latter is understood as an inscrutable nucleus which, "possessing" the individual in his deepest interiority, manifests itself to the world from an early age); or, alternatively, with Elemire Zolla (Descent into Hades and resurrection e The god of intoxication, where however al duende by García Lorca one chapter is reserved), Colin Wilson (The outsider) or Fernando Person. For our part, we limit ourselves to mentioning once again the already mentioned Octavio Paz, who perhaps had in mind something similar to the Jüngerian "original background" and "spirit of the earth" when he wrote:

«Returning to the original death will mean returning to the life before life, to the life before death: to limbo, to the maternal womb. "

As the duende by García Lorca that «works on the dancer's body like the wind on the sand ", even the spirit of the earth theorized by Jünger «does not dwell in privileged and closed spaces. Rather it is legitimate to imagine that it is condensed and evident in certain places, or even in some men, just as electrical energy can make some parts of a material bright»[§67]. Likewise, the arrival of the duende, as can be seen from the text of the Spanish playwright, is marked by a sudden "Radical change of all forms" and from a superhuman possession that is to be connected, in the Western tradition, with theenthusiasm Dionysian and the meeting meridian Great God Pan.

By means of that panic experience, says García Lorca, the duende "He undertakes to make people suffer by means of drama, on living forms, and prepares the stairs for an escape from the reality that surrounds us":

«[…] It hurts, and in the healing of this wound, which never heals, lies the unusual, the invented of human work. "

Texts cited:

- HILLMAN, James: The code of the soul. Adelphi, Milan 1997

- HILLMAN, James: Essay on Pan. Adelphi, Milan 1977

- HILLMAN, James: The dream and the underworld. Adelphi, Milan 2003

- GARCIA LORCA, Federico: Game and duende theory. Adelphi, Milan 2007

- Junger, Ernst: At the wall of time. Adelphi, Milan 2000

- PAZ, Octavio: The labyrinth of solitude. SE, Milan 2013

- WILSON, Colin: The outsider. Atlantis, Rome 2016

- ZOLLA, Elemire: The god of intoxication. Anthology of Modern Dionysians. Einaudi, Turin 1998

- ZOLLA, Elemire: Descent into Hades and resurrection. Adelphi, Milan 2002

Federico Garcia Lorca

"Game and theory of duende"

[...] Whoever finds himself in the bullskin that extends between the Júcar, the Guadalete, the Sil or the Pisuerga (I do not want to mention the lion's mane waves that shake the Plata), hears it said with some frequency: "This has a lot duende". Manuel Torres, a great artist of the Andalusian people, said to one who sang: "You have a voice, you know the styles, but you will never make it, because you don't duende».

Throughout Andalusia, rock of Jaén and shell of Cadiz, people constantly talk about the duende and he discovers it as soon as he appears with effective instinct. The wonderful cantaor El Lebrijano, creator of the debla, said: «The days I sing with duende I know no rivals "; one day La Malena, the old gypsy dancer, hearing a fragment of Bach being played by Brailowsky exclaimed: «Olé! This is what she has duende! " and he got bored with Gluck, Brahms and Darius Milhaud. And Manuel Torres, the man of greatest culture in the blood that I have known, listening to his Notturno del Generalife from Falla himself, uttered this splendid phrase: “Anything that has black sounds has duende". There is no greater truth.

These black sounds are the mystery, the roots that sink into the silt that we all know, that we all ignore, but where does what is substantial in art come from. Black sounds, said the Spanish commoner, and in this he agreed with Goethe who, speaking of Paganini, gives us the definition of duende: «Mysterious power that everyone feels and that no philosopher explains».

So, then, il duende it is a power and not an action, it is a struggle and not a thinking. I heard an old guitar teacher say: «The duende it is not in the throat; the duende it rises inwardly from the soles of the feet ». That is to say, it is not a question of faculty, but of authentic living style; that is to say of blood; that is, of a very ancient culture, of creation in act. This "mysterious power that everyone feels and no philosopher explains" is, in short, the spirit of the earth, The same duende who embraced the heart of Nietzsche, who sought him in his external forms on the Rialto bridge or in the music of Bizet, without finding him and without knowing that the duende pursued by him had leapt from the mysterious Greeks to the dancers of Cadiz or to the strangled Dionysian cry of the Seguiriya by Silverio.

So, therefore, I don't want to get confused about the duende with the theological devil of doubt against which Luther, in Nuremberg, threw a bottle of ink with Bacchic sentiment, nor with the catholic devil, destructive and unintelligent, who disguises himself as a bitch to enter the convents, nor with the talking monkey that l Cervantes' astute Turcimanno takes with him in the comedy of jealousy and the forests of Andalusia.

No. Il duende of which I speak - mysterious and startled - descends from that very cheerful demon of Socrates, marble and salt, which scratched him indignantly the day he took the hemlock; and on the other, Descartes' melancholy devil, small as a green almond, who, fed up with circles and lines, went off through the canals to hear the drunken sailors sing.

Every man, every artist, will recall Nietzsche; every ladder that climbs into the tower of his own perfection is the price of the struggle he endures with a duende, not with an angel, as has been said, nor with his muse. It is necessary to make this fundamental distinction for the root of the work. The angel guides and gives as Saint Raphael, defends and avoids like Saint Michael and prevents like Saint Gabriel.

The angel it dazzles, but it flies over the head of man, it is above it, it branches out its grace and man, without any effort, carries out his work, his sympathy or his dance. The angel of the road to Damascus, the one who entered through the cracks of a small balcony in Assisi, or the one who follows in the footsteps of Enrico Susson, orders and there is no way to oppose the light of him, because he waves his wings. steel in the environment of the predestined.

the muse said and, on some occasions, blows. She can do it very little, because she is already far away and so tired (I have seen her twice) that I had to put half a heart of marble on her. Muse poets hear voices and don't know where, but they are the muse who feeds them and sometimes drinks them. [...] the angel gives light and the muse gives forms (Hesiod learned from them). Bread of gold or fold of tunics, the poet receives rules in his laurel grove. In contrast, the duende it must be awakened in the innermost chambers of blood.

[...] The real struggle is with the duende. We know the ways to seek God, from the rude way of the hermit to the subtle way of the mystic. With a tower like Santa Teresa, or with three streets like San Giovanni della Croce. [...] To search for the duende there is no map or exercise. We only know that it burns the blood like a glass topical, that it dries up, that it rejects all the sweet geometry learned, that it breaks styles, that makes Goya, master in the grays, silvers and pinks of the best English painting, to paint with knees and fists in horrible blacks of bitumen; or who strips Don Cinto Verdaguer in the cold of the Pyrenees, or brings Jorge Manrique to await death in the moor of Ocaña, or covers Rimbaud's delicate body with a green tumbler's dress, or puts dead fish eyes on the Count of Lautréamont in the dawn of the boulevard.

The great artists of southern Spain, gypsies or flamenco, whether they sing, dance or play, know that no emotion is possible without the arrival of the duende. They deceive people and can give you feelings of duende without having it, as authors or painters or literary stylists deceive you every day without duende; it is enough, however, to pay a minimum of attention, and not to be guided by indifference, to discover the trap and put them to flight with their crude artifice.

One time, the Andalusian singer Pastora Pavón, "The girl of the combs", a dark Hispanic genius, equal in fantastic capacity to Goya or Rafael the Rooster, sang in a tavern in Cadiz. He played with her shadowy voice, with her voice of molten tin, with her voice covered with moss, and whether he wove it in his hair or bathed it in chamomile tea or lost it in dark and faraway junipers. But nothing; it was useless. The listeners remained silent. […] Pastora Pavón finished singing in the silence. Alone, and with sarcasm, a small man, one of those little dancing men who suddenly come out of bottles of brandy, said in a grave voice: "Long live Paris!", As if to say: "We are not interested in skills or technique here. , nor mastery. It is something else that interests us ".

Then the little girl of the combs got up like a madman, hunched like a medieval prefic, she gulped down a large glass of brandy like fire in one gulp, and sat down to sing without a voice, breathless, without nuances, with a parched throat. , but ... with duende. She had managed to kill the entire scaffolding of the song to make way for a duende furious and hot, friend of the winds laden with sand, which induced the listeners to tear their clothes almost at the same rhythm as the Antillean blacks of the rite massed in front of the image of Saint Barbara.

The little girl of the combs had to slash her voice, because she knew that the listeners were refined people who did not ask for forms, but for marrow of forms, pure music with a light body to be able to keep themselves in the air. He had to deprive himself of faculties and certainties; that is, to remove her muse and remain helpless, so that his duende come and deign to fight hard. And how he sang! His voice no longer played, it was a gush of blood worthy of her pain and his sincerity, and it opened like a ten-fingered hand on the nailed but storm-filled feet of a Christ by Juan de Juni.

The arrival of the duende it always presupposes a radical change of any form compared to old plans, it gives completely new sensations of freshness, with a newly created, miraculous quality of rose, which produces an almost religious enthusiasm. […] Of course, when this escape is achieved, everyone feels its effects: the initiate, seeing how style overcomes a poor material, and the ignorant, in that 'I don't know what' of an authentic emotion.

[...] Il duende it can appear in all the arts, but where it is most easily found, as is natural, it is in music, dance and recited poetry, since these need a living body that interprets them, since they are forms that are born and die continuously and raise their contours on a precise present.

Often the duende of a musician passes to duende of the interpreter and, at other times, when the musician or the poet are not such, the duende of the interpreter, and this is interesting, creates a new wonder which, apparently, is nothing but the primitive form. This is the case of the induendata Eleonora Duse, who was looking for failed works to bring them to success thanks to her inventive ability, or the case of Paganini, reported by Goethe, who knew how to draw deep melodies from authentic vulgarity, or the case of a delightful girl from Puerto de Santa María, that I saw singing and dancing the horrible Italian song Oh Mari!, with rhythms and silences and an intention that transformed the Italian junk into a hard, erect golden snake. What actually happened in those cases was something new that had nothing to do with what existed before; living blood and science were introduced into bodies empty of any expression.

[...] Il duende [...] it does not come if it does not grasp the possibility of death, if he does not know that he has to patrol his house, if he is not sure of having to cradle those branches that we all carry and which do not have, which will not have consolation. With an idea, with a sound or with a gesture, il duende he takes pleasure in the edges of the well in open struggle with the creator. Angel and muse run away with violin or rhythm, e il duende it wounds, and in the healing of this wound, which never heals, lies the unusual, the invented of human work.

The magical virtue of the poem consists in always being induended to baptize with dark water all who look at him, since with duende it is easier to love, to understand, and it is a certainty to be loved, to be understood, and this struggle for expression and for the communication of expression sometimes acquires, in poetry, deadly characters.

[…] We said that il duende loves the edge, the wound, and approaches the places where the forms merge in a yearning beyond their visible expressions. In Spain (as in oriental peoples, for whom dance is a religious expression) the duende has unlimited power over the bodies of the dancers of Cadiz, praised by Martial, over the breasts of those who sing, praised by Juvenal, and in the whole liturgy of the bullfight, an authentic religious drama in which, like the mass, we adore, and we sacrifices himself, to a God. It looks as if the whole duende of the classical world would gather in this perfect feast, an exponent of the culture and great sensitivity of a people that discovers in man its best anger, its best bile, its best cry. Neither in the Spanish dance nor in the bullfight does anyone enjoy themselves; the duende he undertakes to make people suffer through drama, on living forms, and prepares the stairs for an escape from the reality that surrounds us.

Il duende works on the dancer's body like the wind on the sand. Magically transforms a girl into a paralytic of the moon, or fills with virginal blushes an old beggar who begs for alms for taverns, gives with his hair the smell of a nocturnal port, and at all times works on his arms with expressions that are mothers of the dance of all time. But it is never possible to repeat itself, and it is very interesting to underline it. Il duende it does not repeat itself, just as the shapes of the stormy sea do not repeat.

[...] Spain is the only country where death is the national spectacle, where death plays long clarinets when spring arrives, and his art is always governed by a duende acute that gave it the difference and the quality of invention.

[…] Every art has, as is natural, a duende of different shapes and ways, but all have their roots in a point from which the black sounds of Manuel Torres gush out, ultimate material and common ground shaken by an uncontrollable thrill of wood, sound, canvas and word. Black sounds behind which volcanoes, ants, zephyrs and the great night that surrounds life with the Milky Way have long been in tender intimacy.

Il duende… But where is the duende? From the empty arch enters a mental air that blows insistently on the heads of the dead, in search of new landscapes and ignored accents; an air with the smell of baby saliva, crushed grass and a veil of jellyfish that announces the constant baptism of newly created things.

Interesting connection between Jünger and Garcia Lorca! Thanks for the stimulus!

Thank you! 🙂