Paranormal powers are not encountered exclusively with primitives, but also with yogis, fakiri, saints of all kinds, belonging to all sorts of civilizations. The necessities of the historicist argument forced de Martino to limit his comparisons to the paranormal powers of primitives and those of modern mediums. But the authenticity of the yogis' powers, for example, raises another problem: that of the lucid and rational conquest of these paranormal powers. It is therefore not necessary to consider only a "historical magical world" (the primitives) and a spontaneous but historically inauthentic regression in this world (the mediums): it is necessary to consider another world accessible, in principle, to everyone and at any historical moment.

di Mircea eliade

taken from E. De Martino, The magical world. Prolegomena to a history of magism, Turin 1997, pp. 266-272

originally published in “Critique”, 1938, n. 23

Andrew Long occupies an original place in the history of ethnology. Indeed, he had the merit of "seeing" the problems of the future and of seeing them in all their theoretical consequences and of solving them in a more or less correct way. It is Lang who first revealed the importance of Supreme Beings of the most primitive peoples, anticipating by a quarter of a century the discoveries of Gusinde, Koppers, Trilles and Schebesta among the Fuegini and Pygmies. And it was Lang again who, in 1894, first compared the "Magic powers sorcerers and the resulting beliefs in lower societies, with certain paranormal manifestations (clairvoyance, divination, telekinesis etc.), which the famous Society for Psychical Research he began to collect and study.

The Lang had even proposed that ethnological expeditions include in theirs teams a specialist in parapsychology, more qualified than ethnographers and naturalists to observe and verify any paranormal manifestations in lower societies. As expected, these suggestions were not accepted. But ethnographers and travelers have never stopped collecting and communicating an ever increasing number of "Miracles" performed by sorcerers, shamans, healers. On the other hand, after many hesitations and initial errors, the studies of paranormal psychology have led to concrete results: many scientific institutes continue today, on a more solid basis, the research undertaken sixty years ago by the Society for Psychical Research in London.

Il de Martino it was proposed to first discuss the objectivity of these paranormal phenomena both at the primitive sorcerers that at the medium and subjects of parapsychological research. In a passage of his book he rightly recalls that the polemical attitude, that is of clear refusal, with respect to paranormal phenomena, although it has its historical reasons in a still recent past, has today completely changed. This attitude had a historical sense and function insofar as it was a question, for the Western world, of making its rationalist conception of the universe triumph over the ancient magical-religious evaluations. For certain tactical reasons rationalism was then obliged to deny the reality of paranormal phenomena.

But today, observes de Martino, the universe has been purified of any magical-religious valorization and no risk is taken to rationalism if one observes "objectively" both the "miracles" of primitive sorcerers and the paranormal phenomena of medium. Consequently, in his Magic world, he tries to take stock of these "miracles". Making use of the ethnological documents already used and commented on in his articles on extrasensory perception ["Studies and Materials of the History of Religions", Vol. XVIII, 1942, pp. 1-19 and vol. XIX-XX, 1943-46, pp. 31-84] he cites a number of cases which they refer to paranormal powers of primitive wizards, strictly adhering to well-recorded facts by qualified authors.

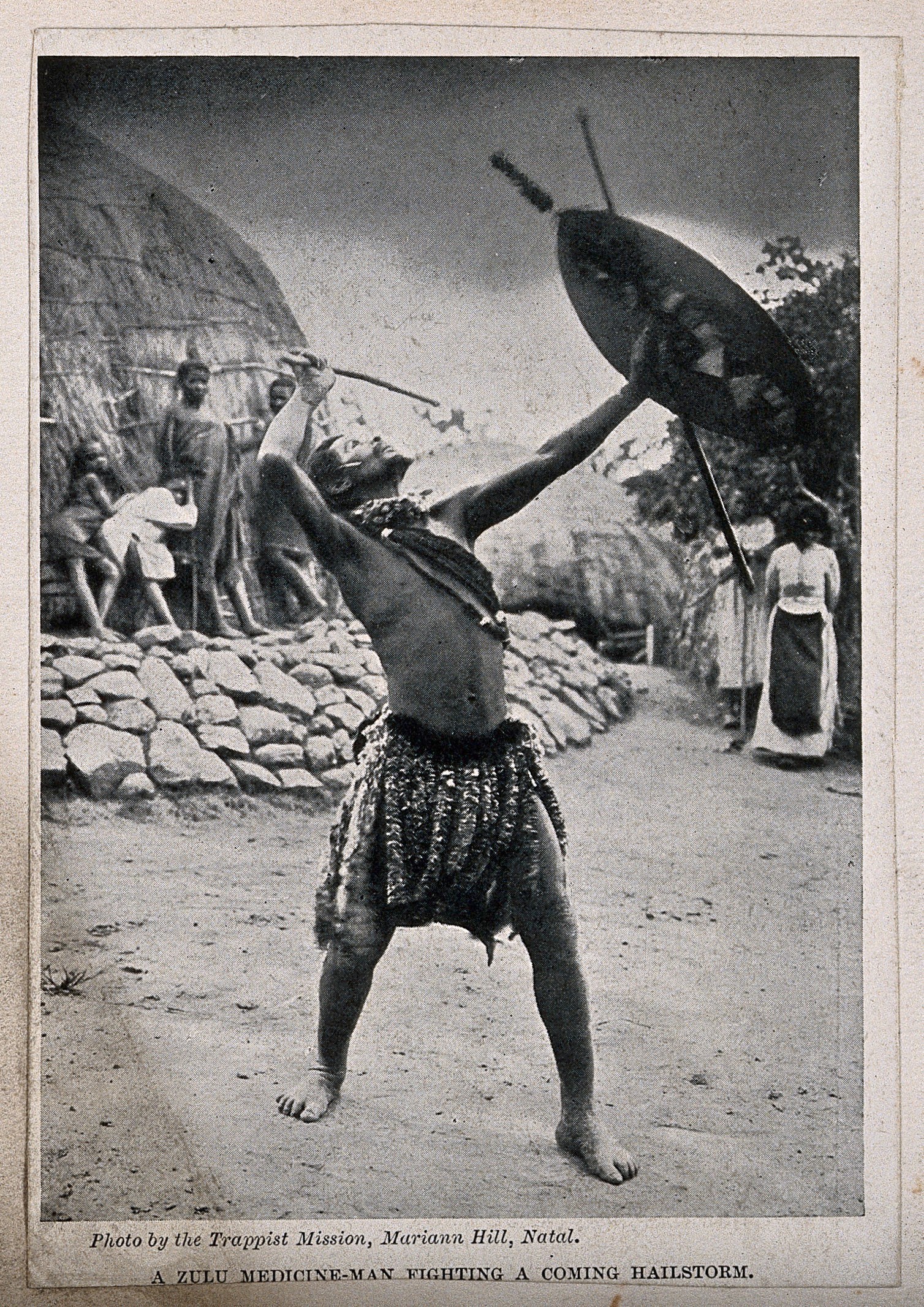

For example he reports, from the Shirokogoroff, some cases of clairvoyance and of thought reading among the Tungus shamans; from Trilles, strange episodes of prophetic clairvoyance in dreams among the Pygmies, such as the case of the discovery of thieves through the magic mirror; cases of very concrete vision relating to the results of the hunt, also here with the aid of the magic mirror; cases of exact understanding, by the Pygmies themselves, of unknown languages; from D. Leslie draws examples of clairvoyance among the Zulus; finally, from many authors and documents that guarantee its authenticity, he mentions the collective ceremony of passage on the fire to the Fiji Islands [it is strange that the author ignored one of the last comparative monographs that appeared on this subject (that of Olivier Leroy, Les hommes salamandres, Paris 1931) which reports many documents relating to the crossing of the fire: one of the best observed cases is that of one yogi of Madras which made it possible to pass a crowd of spectators, even decidedly skeptical, including the bishop of Madras with his entourage. NdA].

Many other paranormal phenomena have been noted among the Chukchis by the Bogoraz, who also recorded the "Voices of spirits" of shamans: such voices were hitherto interpreted as ventriloquism, but the explanation is unlikely, since the voices certainly came from a very distant point from the device in front of which the shaman was. Rasmussen from the Iglulik Eskimos, and Gusinde from the Selk'nam of Tierra del Fuego, have collected many cases of premonition, clairvoyance, and so on. The list, by the author's own confession, could easily be extended.

But these documents are sufficient, since they are chosen among the most certain and clear-cut of contemporary ethnological literature. There is no longer any doubt about the objectivity of paranormal phenomena, many of which have been observed in the medium Europeans. Admitting the reality of such phenomena is in itself a scandal for modern science: accepting the possibility of moving objects at a distance, of reading thoughts, of understanding unknown languages, etc., seems to be tantamount to denying the surest historical foundations of science. However, these phenomena have a character sui generis: they do not allow themselves to be reproduced always and in any environment (remember, for example, the failure of numerous paranormal experiences both among primitive sorcerers and among medium modern).

In consideration of this, these phenomena cannot be considered as belonging to nature in the same way as other phenomena; rather they belong to a "culturally conditioned" nature ie a a nature enhanced by human experience in a certain historical moment, that is, ultimately, to a nature that exists as such only for the primitives and that is integrated into the magical perspective which is theirs. The sense historical of the objectivity of paranormal phenomena is brilliantly discussed by de Martino in the second chapter of his book, "The historical drama of the magical world": the author is an idealist from the school of Benedetto Croce, and in an earlier work [Naturalism and historicism in ethnology, Bari 1941] also attempted to found ethnology on the Crocian conception of history.

As he rightly observes, determining to what extent the magical powers of primitive sorcerers are real is a problem that can only be solved as a function of sense that reality can have in primitive experience. If we consider the reality learned from primitives as identical to the our in reality, understanding not only of paranormal phenomena as such, but also of the magical world in general is inhibited. It is therefore necessary historically interpret this magical world, that is, to rediscover the concrete anthropological situation that leads to the elaboration of such a world. Indeed, as a good idealist, de Martino does not doubt that every "world" is not a creation of man's spiritual activity. If clairvoyance, telekinesis, levitation are real in the magical world of primitives, it is necessary to understand the anthropological situation that made these phenomena possible.

Primitive man, observes de Martino, does not know the "unity of his own person" like the moderns, and it is for this reason that he is perpetually faced with the dramatic threat of losing his being (hence the well-known ethnological and folkloric motif of the "lost soul"), and also in the face of the risk of seeing the world "lost"; more generally, for the primitive nothing è in a decisive way, as well as instead è the world, or how è the soul, for a modern. The risk of getting lost seems to be especially great for the sorcerer, who undergoes so many trials, so much suffering, and who experiences so much loneliness and also so much terror during his initiation. But only in appearance do magical techniques weaken the being: on the contrary, the magician saves himself from the risk of getting lost, organizing psychic chaos with his own will and thus giving a "form" and a "structure" to the spirits projected by his own psychic lability. By saving himself the sorcerer saves the community at the same time, and by the fact that he has identified the spirits, he also masters them.

Ultimately, magical ideology is a real defense of the precarious conscience of the primitives. For them the world is never date, and being never is guaranteed, and this is the reason why they feel the anguish of no longer being able to maintain themselves as a presence before the world. For them, therefore, all paranormal phenomena are real, inasmuch as they are made possible by their psychic condition and also by their physical world, which is always, let us not forget, "A culturally conditioned nature". As regards the paranormal powers duly verified in our day in the experience of paranormal psychology, these powers, although real, are however inauthentic, compared to the our reality, as it has been created and made valid in the course of our history: which is equivalent to saying that, real and authentic in the magical world that made them possible, the powers of the medium moderns are real but inauthentic in our own world (roughly in the sense that i troglobes, which survive after the end of the secondary period in the bottom of the caves, are living fossils).

The consequences ofidealistic interpretation of de Martino they can be easily predicted. Reality, even the cosmic one, is always historical, that is, conditioned by the level of the human condition. Thus, for example, spirits exist for those who participate in a magical world, but they cannot exist for the spiritualists of contemporary Europe, because our history prohibits the objective existence of the souls of the dead; consequently it is objectively possible for a primitive sorcerer to speak with the dead, but the voice of the dead cannot exist for modern spiritualists. Since Bogoraz has recorded on his phonograph the "voices of spirits" with which the Tungus shamans entertain, the reality of these voices appears to be scientifically assured. It is only a question of deciding whether this reality belongs exclusively to a certain "history" (the magical world of the Chukchi), or whether it does not qualify as universally valid.

De Martino refuses to accept as a metaphysical structure of reality what is only "a determined historical result". He keeps himself in the purest perspective of historicist idealism: the world never exists date, it is continuously done by man himself, by virtue of his creative will, and ultimately by his "history". We are therefore entitled to conceive a plurality of physical universes: to conceive, for example, a second universe in which men could enjoy the power of levitation, become invisible and walk with impunity on hot coals, in contradiction with the physical laws of our first. universe. So why not also conceive a universe in which men could become immortal and divine? Everything depends on history, that is, on the will of man [...].

How is it possible to admit the possibility of two natures? This was Wundt's question about the reality of paranormal phenomena that he, as a consequent materialist, was obliged to deny: how to reconcile a universe governed by the laws of Copernicus and Galileo, and another, mysterious, controlled by laws known only by medium able to read minds, to move objects at a distance and to foresee the future? No doubt Wundt's indignation betrays a naturalistic mentality; but doesn't the same paradox also undermine historicist idealism when it tries to understand paranormal phenomenology? Since, for example, how can we suppose that men continue to live after their death in a certain historical civilization, and that they are definitively annihilated in another? Certainly it is conceivable, according to the claim of certain occultist traditions, that survival is a magical-religious construction made possible only by an initiation and therefore limited to a elite; but it is incomprehensible that in a primitive society all the dead must survive, while in our modern world all the dead must be annihilated, and this for the simple fact that the stories of these two types of civilization are different […].

On the other hand, paranormal powers do not meet exclusively with the primitives and aberrant subjects of the Western world, but also with yogi, fakirs, saints of all kinds, belonging to all sorts of civilizations. The necessities of the historicist argument forced de Martino to limit his comparisons to the paranormal powers of primitives and those of medium modern. But the authenticity of the powers of the yogi, for example, poses another problem: that of conquest Glossy e rational of these paranormal powers. It is therefore not necessary to consider only a "historical magical world" (the primitives) and a spontaneous but historically inauthentic regression in this world (the medium): another world must be considered accessible, in principle, a all ed at any historical moment (since the yogic "powers", for example, are not the exclusive privilege of the Hindus, nor of a particular historical epoch, since they are attested from the most ancient times to the present day). In a study published in 1937 ["Folklore ca cunoastere instrument": Reprinted in the volume"Insula him Euthanasius", Bucharest 1943, pp. 28 ff.], Starting from this same encounter between ethnological documents and paranormal facts, we have tried to solve the problem of the reality of paranormal powers in a completely different perspective.

The reservations we have made take nothing away from the indisputable merits of the research undertaken, with multiple competences, by the Italian scholar. His book stands out in its abundant and often inert ethnological production, not only for the new points of view but also for the philosophical interest it presents. Too often one gets the impression that Western philosophy maintains itself in a sort of "provincialism" which prohibits it from accessing the great currents of human thought (the primitives, the East, the Far East). Books like this by de Martino help us to rediscover the true perspective of an integral humanism in which the experience of a "primitive", of a yogi or a Taoist acquire the right of citizenship alongside the best traditions of the West.

3 comments on “Mircea Eliade: "Science, idealism and paranormal phenomena""