The cult of generative powers that permeated the ancient Celtic (and pre-Celtic) religion remained in vogue in Ireland even after the advent of Christianity, to the point that some scholars speak of a "Celtic Christianity" which, under the veil of the new cult, would have kept the ancient sacred doctrines intact: one of the most meaningful clues in this sense is the representation of the Sheela-na-Gig first in megalithic sites and sacred wells and, later, in Christian churches themselves.

di Marco Maculotti

The representation of the Sheela-na-Gig, although probably belonging to the symbolic art of the populations settled in Ireland before the Celts, is generally related, without distinction of any kind, with the most varied Celtic goddesses: tailtiu, goddess of cereals whose mythical sacrifice to Lammas is remembered; Tlachtga, goddess of the dead celebrated in Samhain, Macha, goddess-mare connected to the north and Yule; Brigit, goddess of fertility and rebirth celebrated in Imbolc; Tea, goddess of sovereignty honored in Beltane, and other goddesses of sovereignty such as Medb, Cailleach and Éiru. All these deities were already venerated in pre-Celtic Ireland and possessed sanctuaries for worship, all located on hills considered sacred, the same ones that following the advent of Christianity were linked in folklore to the invisible people of the Sidhe [1].

The historical evidence that has come down to us, however, allows us to find with certainty the origins of the symbol of the Sheela-na-Gig at the dawn of Niall dynasty of the Nine Hostages, supreme king of Ireland from 378 to 405 AD, whose descendants are kings of Irish, Scottish and English territories, as well as many of the holy founders of most of the early Irish monastic institutions [2]. On the other hand, it is established that many of the earliest Christian priests in Ireland were Druids who, faced with the choice between accepting the new faith or facing death, opted for survival and tried to integrate the Christian religion with the symbols and archetypes of the ancient cults [3]:

« When the Druids became priests, they poured all their ancient Druid knowledge about history, genealogy, law and cosmology into the new faith. […] An exceptional event, in Ireland the new religion was naturalized by a pre-existing intelligentsia. "

The "Celtic Christianity" and the origins of the Sheela

It is therefore not surprising that the greatest number of Sheela-na-Gig are found in first Christian monasteries founded by these first monks-druids, in particular those of the two "schools" of Santa Brigida need Saint Columba (not to be confused with Colombano); the "school" of St. Patrick, on the contrary, was closer to the dogmas and symbols of the Church of Rome. Other Sheelas, although in much smaller numbers than those found in the British Isles, are found on the European continent (11 in all), some in the Northern France along the Atlantic coast, others along the path followed by pilgrims to reach Santiago de Compostela in Spain, a sacred place and a pilgrimage destination even before the Christian era.

On the other hand, the first Christian monasteries in Ireland were built on the same sites that previously housed the temples of the ancient religion. The first churches, the so-called airtech, were built with the wood obtained from the demolition of the sacred oak groves in which the druidic rituals took place. The construction of the village then developed around the wooden church: at that time "the whole monastery resembled a village of wooden huts", comparable to a beehive [4].

Before they moved on to building stone churches, the Sheela-na-Gig came carved on stone menhirs or stems, not infrequently placed next to a sacred well. Tradition often links Sheela's sacred power to the recitation of prayers at the well she is attached to, or to the ritual practice of hanging scraps of cloth and souvenirs such as votive to the branches of the hawthorn, which is considered in the Gaelic tradition the "tree of the fairies" (fairy tree) [5]. It therefore appears evident that the symbolic sphere of the Sheela-na-Gig is that of lower waters (or underground), that fluid, volatile and pre-formal world of the subconscious, the dimension in which the Fairies and the souls of the dead.

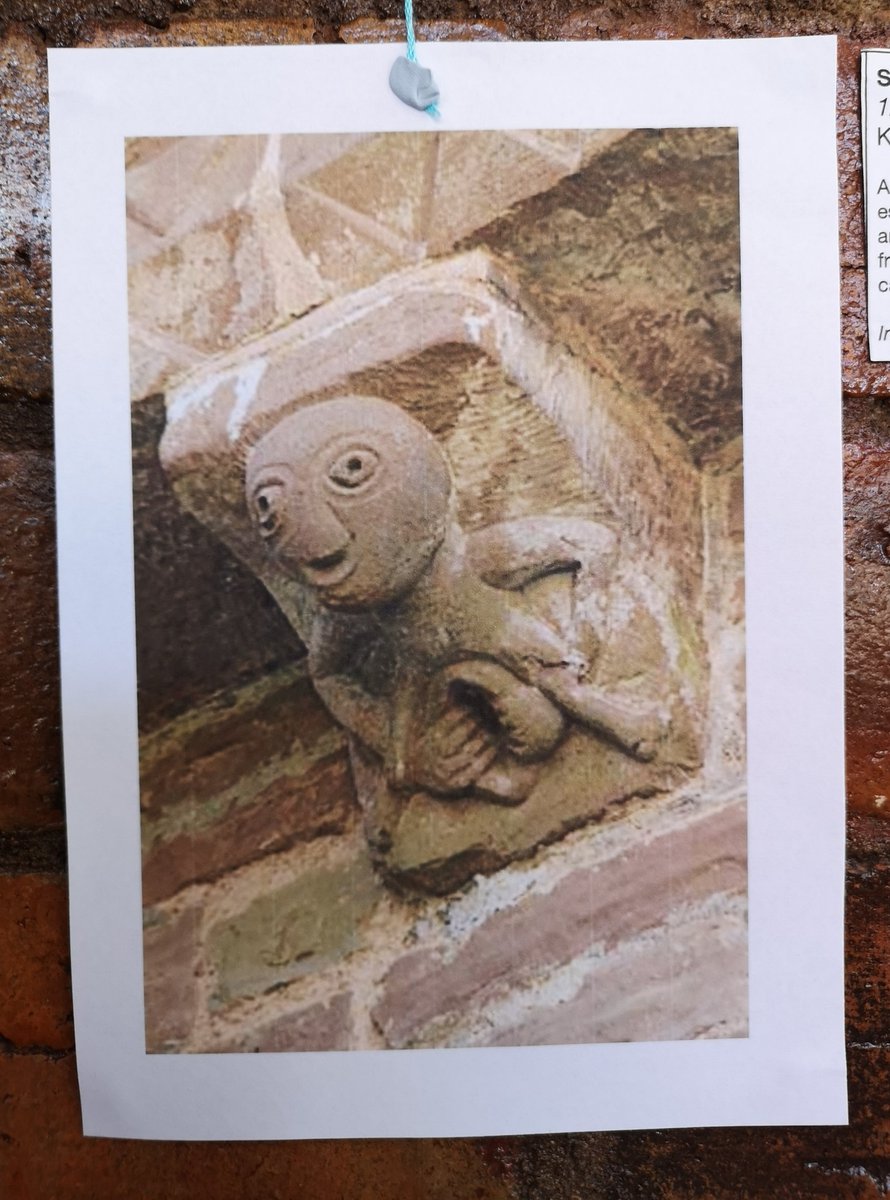

Most of the Sheela-na-Gig, however, are found in churches built between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries in the Romanesque style - although often the depictions of the aquatic goddess are significantly more worn than the rest of the stone walls, betraying greater antiquity and a survival from the most ancient buildings to later churches. Others are much older: that of Sierkieran, in the county of Offaly, “has many characteristics of a pagan idol, including holes in the top of the head that could have held head ornaments such as deer antlers or flowers» [6]. In this village, the first Christian monastery dates back to 350 AD, which suggests that the Sheela found here may also date back to an earlier era.

![Photograph of the Sheela na gig, Church Stretton, Shropshire [c.1930s-1980s] by John Piper 1903-1992](https://axismundi.blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/tga-8728-1-31-140-1_10.jpg)

Healing rituals

Representations of the Sheela-na-Gig were sometimes found at sites where they took place healing rituals: This is the case with the Tomregan stone in Cavan County, which some scholars claim is a depiction of San Bricín, one of the founding saints-druids who lived and taught at the local abbey-university. Recalling the symbolism of the Sheela in the open-legged position, the work while depicting a saint was apparently not considered indecent, despite the exposure of the genitals.

However the Christianization of cults, here as elsewhere, did not at all go hand in hand with the elimination of the ancient religion: as a demonstration of this it is interesting to note how around the Tomregan site, in addition to the foundations of the church and a circular tower, the remains of some sweat huts were found (similar to those in which the Scythian knights of the Eurasian steppes reached ecstasy by deeply breathing hemp smoke) and those of some medicinal plants, probably used in healing rituals. In the surroundings there is also still today a sacred well with an ancient stone boundary wall [7].

It was above all the Christianity of the school of Santa Brigida, strongly linked to the cult of goddess Brigid and its ancient rituals, to perpetrate ancestral healing practices throughout the Irish Middle Ages. According to tradition Bridget founded thirty convents, including that of Kildare built in 480, where his nuns (or perhaps it would be better to say vestals) continued to practice the ancient disciplines to which they were traditionally used before the advent of Christianity, such as "obstetrics, medicine, herbal medicine, the production of food and dairy products, crafts and arts such as poetry, music, metallurgy and the practice of law " [8]. At that time, the "parish of Brigida" included the central area of Ireland (being the "current" of St. Patrick located on the east coast and that of St. Colomba on the west), and it is certainly no coincidence that it is in this area that the greatest number of Sheela representations have been found.

La Sheela, megalithism and the cult of generative powers

Another Sheela-na-Gig is even found in the archipelago of Orkney, in insular Scotland, precisely inside the church of Kirkwall. At the time these islands were inhabited by Pitti, and Christianity was imported by Saint Colomba on a journey made to meet their king, Brude. Nonetheless, even before the colonization of the Picts, the archipelago had many centers of worship formed by mounds of megalithic stones and corridor tombs such as those of Irish or Malta sites: it is therefore impossible to trace with certainty the antiquity of the symbol in these territories. Another representation is found in the city of York in Yorkshire, England, which at the time was located in the center of the Northumbria region, often identified as the birthplace of "Celtic Christianity" [9].

Also very ancient must be the Sheela-na-Gig on the Adamnan stone, near the sacred hill of Tara, where the goddess is revered in her role as giver of sovereignty. Near this stele where the Sheela is carved is a small boulder in the shape of lingam representing its male equivalent; the pair of stones is known as Bloc e Bluigne and are considered epiphanies of the two aspects of the divine, the feminine and the masculine, which right here in Tara meet ritually in ieros gamos at the time of the election of new ruler [10].

On the other hand, from the publication of Golden bough from Sir James Frazer onwards, the fact that the cult of generative powers was very much in vogue in the British Isles during the pagan era certainly cannot be a novelty. What is surprising instead to realize is how often, thanks to the druidic "infiltration" in the priestly ranks of the nascent Christian clergy, such beliefs and practices have remained alive even in the era officially considered to be fully Christian. It is remarkable in this regard the discovery of "phallic" megaliths buried under the altars of English churches dating back to the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, therefore many centuries after the official transition from paganism to Christianity [11]:

"The partial destruction of religious buildings by German bombs dropped during World War II led Professor Web, an expert in medieval religious architecture, to discover that 90% of all English medieval churches he examined had main altars a stone lingam. "[...] that original symbol of the ancient Cult of Fertility, spread all over the world: the universal Phallus thanks to which all animal life was generated". "

The initiatory symbolism of the Sheela

And the symbolism of the Sheela-na-Gig seems to be complementary in what way to that of the "universal Phallus": analogous indeed to the Visica Piscis, To Yoni Hindu and Egyptian hieroglyphics kteis (as well as similar to That of the T'ao T'ieh oriental or del Kaalamukha Indian), represented, as he writes Maureen Concannon [12],

" […] at the same time a mouth and a gateway to the spiritual world, to the chamber of initiation [...] a birth canal placed between the material and spiritual realms. Irish tradition had retained this symbol of the Great Mother: her body represented both the entry and exit from life itself. "

Indelibly linked to the symbolic sphere of the "lower waters" (or "underground"), the Sheela-na-Gig therefore seems equivalent to the cavern or the underground cave, or to the hollow tree or to the equally hollow hill in which the Sidhe, the invisible people of the deceased and of the feral entities. It is well known that traditionally the Irish 'believed that the waters edge was always a place where the eicse - "wisdom", "poetry", "knowledge" - was revealed ": it is precisely this "border area" pertaining to the geo-mythical sphere in which the symbolic power of Sheela is revealed. They are these "Places without space such as that between the foam and the water or between the bark and the tree" where, in modern folklore, exiled spirits can be confined [13].

Similarly, in Christian era the Sheela was symbolically connected to the transformation to which the faithful were subjected after entering the womb of the "Mother Church", as Concannon comments [14]. In this we can find counterparts in the ethnographic literature concerning the so-called "primitive" peoples, in whose rituals the initiation hut is sometimes described as the belly of a "monster / demon" which neophytes must enter to access the sacred / initiatory dimension . This ritual experience, which we can define as "be swallowed by the monster"(Symbolism also maintained in the Old Testament tradition in the episode of Jonah and the whale), is clearly an experience of death and rebirth: the faithful enter the dark belly in a certain frame of mind and emerges, at the end of the religious function, in another, as if reborn and transformed ontologically.

On the other hand in the Celtic countries, as you note Jean Markale, who are "the divine Mother knows the roads that lead to the Other World, and she is the watchful guardian of them: in Brennilis (Finistère), Notre-Dame de Breac'h Ilis watches over the marshes of Yeun Elez, where, according to local tradition, the gates of Hell are located " [15]. The Mother goddess thus becomes "the one towards whom the dead go to be regenerated and acquire a new birth in a world parallel to that of perceptible relativities" [16], which may be the legendary "apple islands" of Avalon like the invisible and "underground" world - because it is superimposed on our own - gods Sidhe.

The Sheela through the ages

"Celtic Christianity" flourished in the period between the fourth and eighth centuries, then suffered a setback with the Viking invasions. In addition to the raids and devastation brought by the latter, the Christian currents closest to the ancient spirit also suffered the ideological attack of the Church of Rome, to the point that "the cult of the Sheela as a symbol of the Great Mother was labeled as one of the pagan 'of the Church of Ireland that the Church of Rome wanted to' reform '. In Annals no mention is made of either the carvings or the name 'Sheela', although her images were present in all the most important centers of Christianity in Ireland " [17]. According to Irish historian and psychologist Maureen Concannon [18]:

« The Sheela symbolized the eternal truth of death and transformation. Death itself became something to fear for the Church of Rome, as it rejected the psychological truth that every form of life, having reached its end, returns to the Great Mother in order for regeneration to take place. In the XNUMXth century, the Church of Rome prohibited the singing of some ancient Irish hymns because they dealt with the theme of death. "

Gradually the Sheela-na-Gig suffered a process of concealment and elimination: "Slowly they transformed from symbols of the goddess into symbols of immorality, acting as a warning against sexual excesses" [19].

Starting from the thirteenth century, despite the continuous flow of preaching friars from the continent to Ireland (Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians) and the closure in the following decades of more than 200 "Celtic" monasteries, it opens with the Norman invasions a new chapter in the Sheela saga: the most recent invaders began to exhibit her inside the castles as a sign of the legitimacy of their power. There are 33 Irish castles that have images of Sheela that have reached us intact, all built over a period of time ranging from 1250 to 1500, a period usually remembered as "Gaelic RenaissanceBecause he saw the alliance between the Gaelic chieftains and the new Norman colonizers [20].

Other darker periods followed, for the Sheela-na-Gig as for the Celtic culture as a whole: first the conquest of Ireland by the Tudors (1534-1603), with the Protestant Reformation and Elizabethan colonization, then the "flight of the conti »in 1607 after the failure of the rebellion that broke out in 1595, finally the scourge of Cromwell. Thus it was that the Sheela, deprived of the adoration of the Gaelic aristocracy and eliminated from the traditions that it was allowed to study in schools became part of folklore: thus was born the generic character of Banshee, or "fairy woman," who wept to predict the deaths of members of dynastic families. A myth perfectly in line with the tormented soul of the Irish after the physical elimination and the daring flight abroad of the last survivors of what was the Gaelic aristocracy.

Note:

[1] Concannon, The sacred female. Sheela, the god of the Celts, p. 51-2

[2] Ibid, p. 55

[3] Ibid, p. 59

[4] Ibid, pp. 60-1

[5] Ibid, p. 63

[6] Ibid, p. 62

[7] Ibid, p. 65

[8] Ibid, p. 68

[9] Ibid, p. 73

[10] Ibid, p. 81

[11] Ibid, p. 103

[12] Ibid, p. 93

[13] Alwyn and Brinley Rees, The Celtic heritage. Ancient traditions of Ireland and Wales, P. 288

[14] Concannon, op. cit., p. 96

[14] Markale, Celtic Christianity, P. 222

[16] Markale, Wonders and secrets in the Middle Ages, P. 119

[17] Concannon, op. cit., p. 84

[18] Ibid, p. 86

[19] Ibid, p. 89

[20] Ibid, pp. 110-2

Bibliography:

Maureen Concannon, The sacred female. Sheela, the god of the Celts, Arkeios, Rome 2006

Jean Markale, Celtic Christianity, Arkeios, Rome 2014

Jean Markale, Wonders and secrets in the Middle Ages, Arkeios, Rome 2013

Alwyn and Brinley Rees, The Celtic heritage. Ancient traditions of Ireland and Wales, Mediterranee, Rome 2000

Hello, I have read your publication on Sheela-na-gig. I would like to have a contact, even via e-mail for further information on an image of Sheela-na-gig, found in a fresco in Italy.

I leave my email address: er.artemisia@hotmail.it. Emanuela

Good morning Emanuela, you can write to this email:

marcomaculotti@gmail.com

MM