Blake's proverbial visions, in addition to having directed his religious life, also influenced his entire artistic work; Alexander Gilchrist, his official biographer, related them to the so-called "lucid dreams", that is to say with the ability of a subject, during the dream activity, to maintain a conscious lucidity, allowing the ego manifest within of the dream of consciously understanding the experience emerging from the subconscious.

di Francesco Ramorino

cover: William Blake, “Pity”, 1795

The literary sphere is often linked to the inscrutable and symbolic microcosm of the dream. Numerous poets in the history of world literature have often been referred to as 'dreamers', 'visionaries' and, at times, even 'prophets'. These three characteristics find their common denominator in William Blake; English poet of the Romantic age who uses his 'visions' as fuel to fuel his creative forge.

Thanks to Alexander Gilchrist - William Blake's official biographer - we know for sure that already at a young age the poet often sought shelter in his imagination and in his dreams to avoid the too rigid education of his father James. This data is of fundamental importance, since most likely it was precisely this need to escape from a pre-established reality that induced the subconscious of the young Blake to lead to what we now know as "lucid dreaming". In order to understand how it is possible to find a connection between the English poet's situation and lucid dreaming, one must understand what is meant when referring to lucid dreaming.

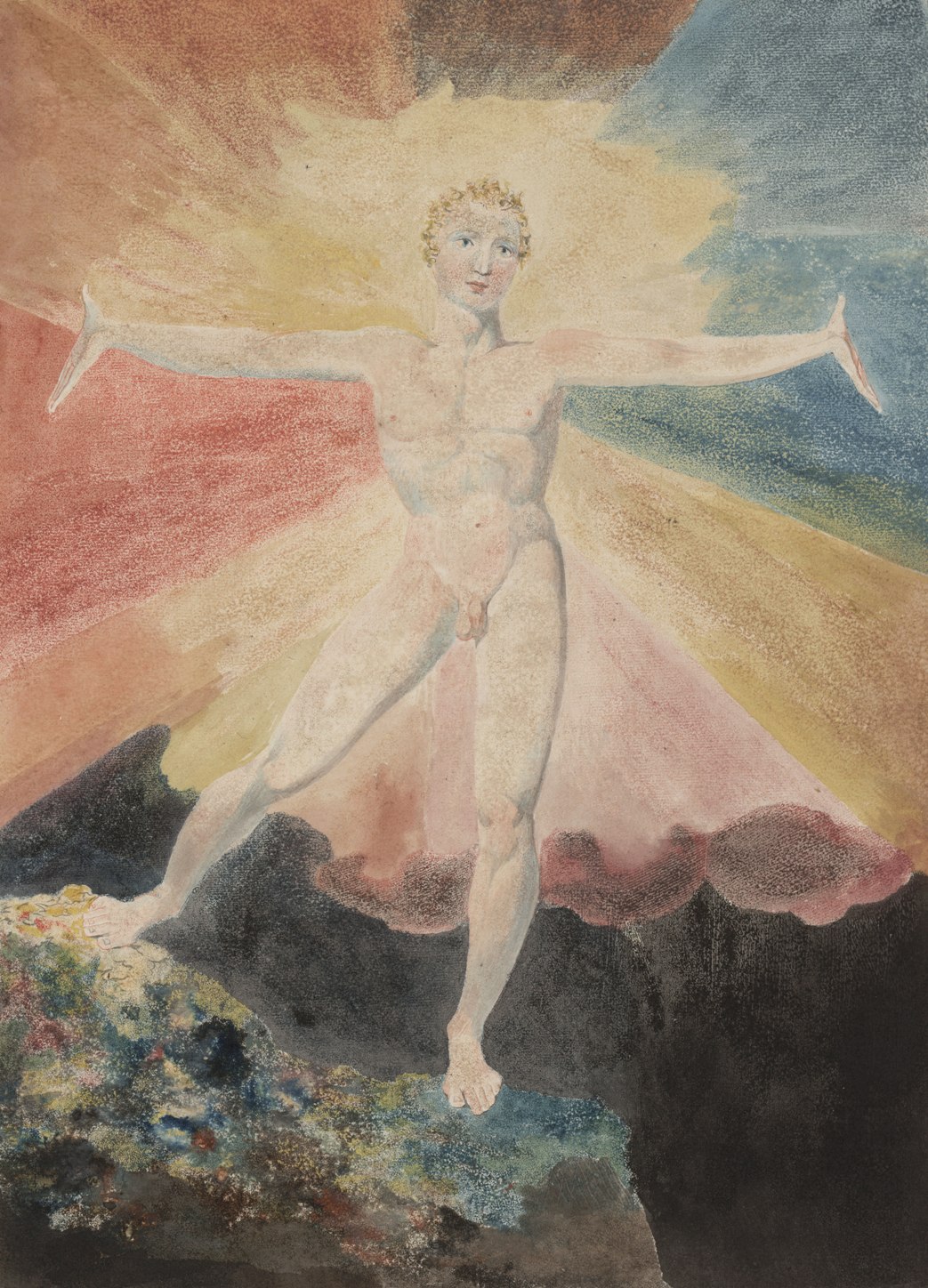

William Blake, "Albion", 1794-6

William Blake, "Albion", 1794-6

The minting of the term "lucid dream" it is often attributed to the psychiatrist Frederik Willems Van Eeden, which in 1913 published an essay for The Society for Psychical Research entitled A Study of Dreams [1]; despite this, the denomination first appeared in The Rsêves et les Moyens de les Diriger di Léon d'Hervey de Saint-Denys, in 1867. Regardless of when the term was first conceived, it is important to understand that both authors refer to ability of a subject to maintain a conscious lucidity, allowing the ego manifest within the dream to understand its presence in the dream reality [2].

By doing so, the subject may even be able to gain control of the dream, manipulating it to his liking. In terms of the study of the dream world, two of the most eminent figures are undoubtedly the Austrian psychoanalyst, philosopher and neurologist Sigmund Freud and his pupil, a psychologist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung. It is precisely the interpretation of the dream that represents one of the key differences between the Jungian and Freudian schools of thought. Indeed, Jung himself rejects the idea expounded by Freud in his own Die Traumdeutung (1899) (or "The Interpretation of Dreams"), or that dreams intentionally hide their meanings. According to Jung [3]:

"[...] dream is a spontaneous self-portrayal, in symbolic form, of the actual situation in the unconscious »

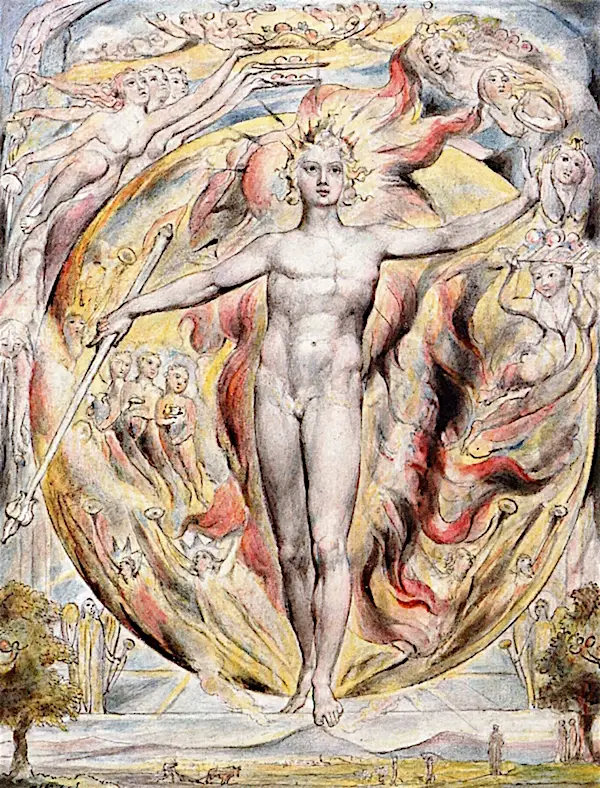

William Blake, "The Sun at His Eastern Gate", 1820

William Blake, "The Sun at His Eastern Gate", 1820

According to Jung's theories, the difficult understanding of dreams derives from the complex symbolic and metaphorical language used within the dream world. Languages, the latter, substantially different from that used during the waking period [4]. Finally, to have a more complete understanding of what will follow, it is equally important to underline that Jung not only accepts Freud's idea that past experiences and / or traumas can pour into the dream, but supports the possibility through his thesis that the subject can visualize the outcome of future events or projects [5].

Despite what was reported, neither psychoanalysts directly analyzed lucid dreaming. Freud merely acknowledges its existence by adding a note in a later version of The Interpretation of Dreams, while Jung - even if in a fairly primeval period of his career - he limited himself to arguing the impossibility of "lucid dreams"; only to be denied once he came into contact with the Tibetan-Buddhist tradition [6].

One might wonder what William Blake has to do with the above psychoanalytic theories. Well, the whimsical and intoxicated spirit of freedom and unconsciousness that only childhood can give will accompany him for most of his life. It is important to understand that in relating to Blake, it is not possible to schematize or constrain his philosophy or mindset, since the same Blake is shown to be strongly opposed to any kind of power or construct. This iconoclastic tendency towards traditions and established powers can be seen in every area of the poet's life; starting from the political one, which led him to approach illustrious personalities of the time such as Thomas Paine and to sympathize with events such as the French Revolution [7], to the religious one.

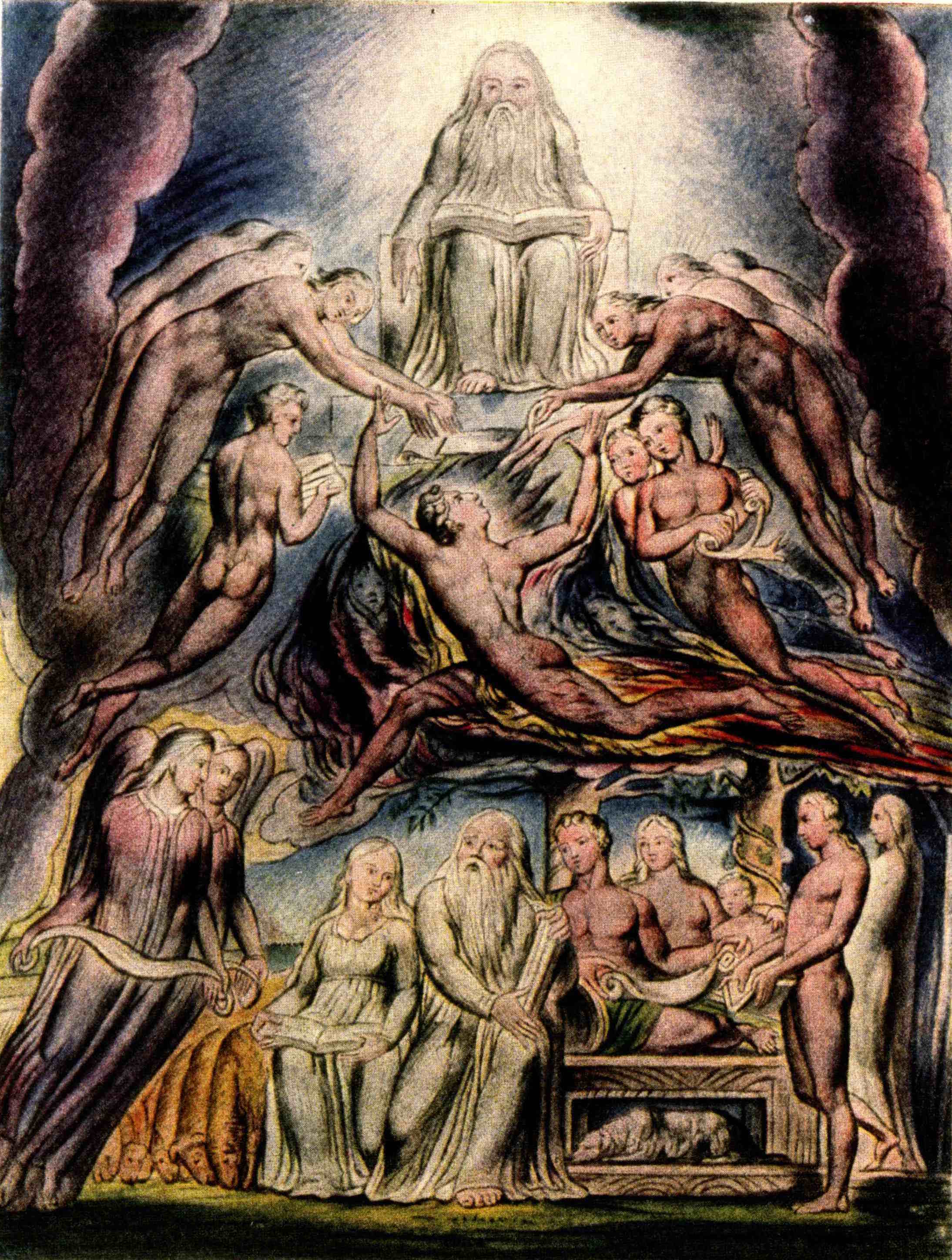

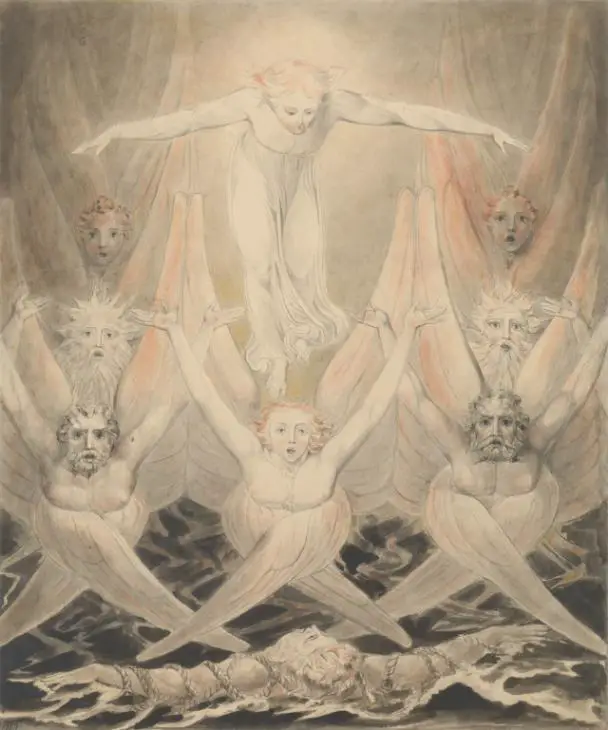

William Blake, "Satan Before the Throne of God", 1825

William Blake, "Satan Before the Throne of God", 1825As regards the latter, in fact, it is possible to note the high number of creeds that the poet came up with, separating characteristics congenial to him from those irreconcilable with him, with the sole intention of create one's own feeling free from any kind of institutionalized influence. This continuous research led Blake to approach several prominent figures in the religious landscape of the eighteenth century. One of the most important figures that Blake affiliated with in this area was Immanuel Swedenborg. According to the biographer himself, Swedenborg turned out to be the most similar and influential personality for the poet, not only from the point of view of thought, but also as regards the visionary and "in faculty for theosophic dreaming» [8].

By understanding this, it is now possible for us to approach the idea that, when in William Blake's life we speak of saving, revealing or terrible visions, we are referring to nothing but vivid dreams, and only then will it be possible to talk about lucid dreams. The first proof of this can be found in the work of Alexander Gilchrist. The biographer himself points out several times that the time of day in which the poet tended to be caught by these 'visions' was always during the night. The first example of vision can be found between the ages of eight and ten at Peckham Rye park, where the poet was entranced by the vision of "a tree filled with angels» [9]. Once back home, the young man told the experience of him to his parents, managing to avoid a harsh punishment from his father only thanks to the intercession of his mother. Although the very young Blake was not aware that he was inside a dream, the factors that could have caused a vivid or "pre-lucid" dream [10] they are quite evident. Following the idea that vivid dreams can be caused by severe periods of stress [11], from traumatic experiences [12], by emotional repression and may represent a kind of psychotherapy induced by our state [13]; it is possible to hypothesize that given the distinctive freedom of mind and thought that characterized Blake even at a young age, the limiting and rigid educational approach of his father James - especially as regards the religious sphere - induced the young man to take refuge in the dream world, dreaming exactly what his father imposed on him. We know that Blake's entire life was marked by 'visions' - including a vision that Blake had at the age of four, which has not yet been attested to be true. [14]. Visions that affect not only his perception of reality, but also to mark his entire artistic production.

Thomas Phillips, "Portrait of William Blake", 1807

Thomas Phillips, "Portrait of William Blake", 1807

Among the many visions we can remember the one had by the poet inside Westminster Abbey, where Blake was relocated by James Basire - his mentor and teacher as regards the art of engraving - to work alone given the high number of taunts. from his colleagues [15]. Precisely during this period of complete alienation and self-denial, as Gilchrist himself maintains, Blake's imagination was so stimulated that he saw, beyond the shapes of the statues, the sometimes more vivid and real forms of the ghosts of the past, inducing a 'vision' of "Christ and the Apostles», and transforming the ghost of the past into a "family companion» [16] Blake himself later claimed that he had, not only seen, but even interacted with the archangel Gabriel who would describe Raphael's works to him [17]; or the time when, walking through the fields, he saw "haymakers at work, and amid them angelic figures walking» [18]Although it has already been specified several times that Blake will be surprised by these visions in isolated places and at times of the day relatively close to the night, the latter vision described would seem to respect neither of the two predetermined characteristics. Precisely in this regard, the Jungian theory of dreams comes to our aid. According to Jung, in fact, there are two levels of the dream: objective and subjective. The objective level would re-propose within the dream "dreamer's relation with the external world, that is, with the people, events, and activities of the dreamer's daily life» [19]; while the subjective level would deal with representing the psyche through the use of figures or symbols that represent the personification of the subject's thoughts and sensations [20]. It is precisely by following the Jungian theory that it is possible to argue that the objective level of the dream caused him to visualize something very familiar to him - given the numerous daily walks around the fields. [21] -, overlapping with the subjective level that would have given birth to the evanescent figures coming from hyperuranium.

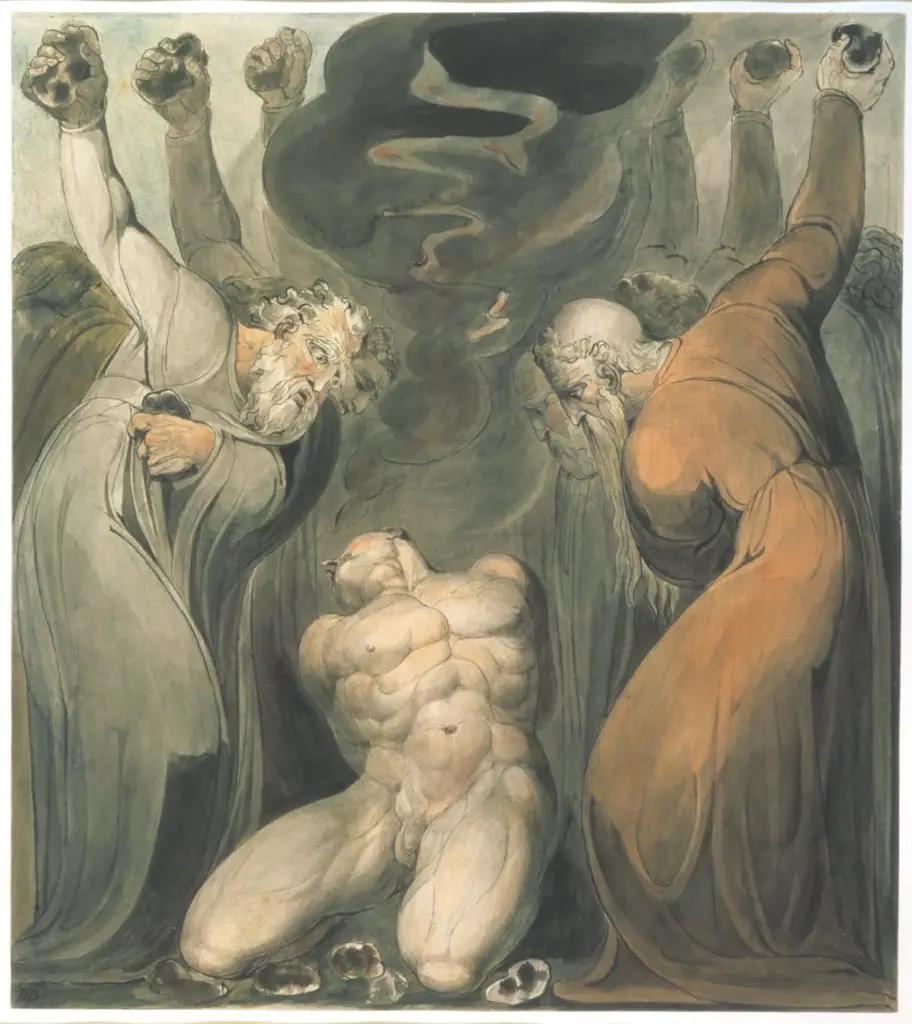

William Blake, "The Blasphemer", 1800

William Blake, "The Blasphemer", 1800

The irrefutable proof of what has been said up to now is a particularly traumatic event for the poet. Event that will turn into a real resonance chamber for Blake's imaginative and dreamy capacity, increasing the intensity of his visions. In 1787 his brother Robert Blake, who for years had shared the house with the poet and his wife Catherine, passed away [22]. Given the great affection that bound the poet to his brother Robert, the long waking period that preceded his departure represented - as witnessed by Gilchrist - the most profound moment of despair that Blake has ever faced in his entire life. Through the biographer's words it is possible to understand how the time spent at his brother's bedside - a two-week period in which Blake refused to close an eye [23] — as much as death, we changed Blake, also asserting that [24]:

"The mean room of sickness had been to the spiritual man, as to him most scene were, a place of vision and of revelation; for Heaven lay about him still, in manhood, as in Infancy it lies about us all. "

The year following his brother's death will represent a tumultuous sea of consoling and revealing dreams, who will accompany Blake in the drafting of one of his best known works: Songs of Innocence. The poet, uncertain about the method of publication given a hostile and refractory environment to a poetics so particular and far from the classical canons of the time, spent numerous days and endless nights to solve the dilemma. The answer, as usual, came through a vision - although Gilchrist himself implies that it could be a dream - in which, the brother, like the more proverbial Virgil, suggested the answer to the poet, guiding him to the exit of his own personal hell. Thus it was that in 1789, Blake self-published the first edition of Songs of Innocence, dealing entirely with the costs of printing and binding, adding numerous engravings relating to some of the works contained within the volume. According to Jung, a further function of the dream would be precisely to give "perspective of future events". In affirming what has been said, Jung does not intend to argue that dreams have some premonitory power, but that they can evoke unconscious solutions to problems that afflict the daytime life of the subject.

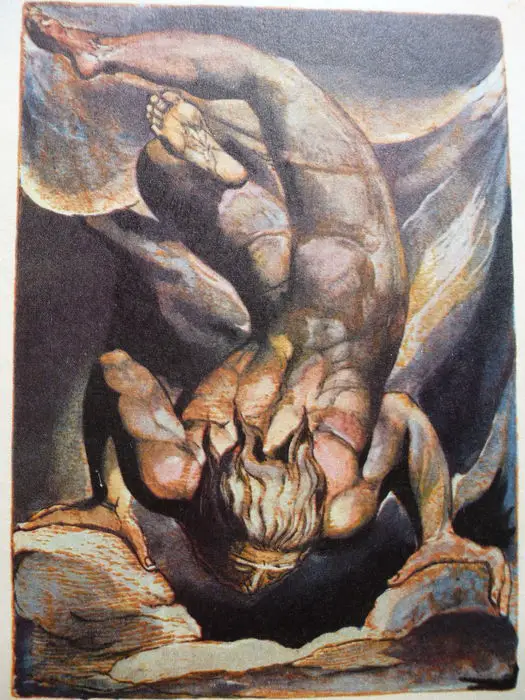

William Blake, "Man Floating Upside Down", 1794

William Blake, "Man Floating Upside Down", 1794In conclusion, following what has been illustrated, it seems natural to the writer to hypothesize that what within Blake's life will be described as 'visions' - both by himself and by the biographer - can be considered as unconscious projections created by the poet's psyche same primarily in an attempt to escape the rigid upbringing of his father. These vivid dreams, mostly of a religious background precisely because of the paternal teachings, will accompany Blake throughout his life, acting as an imaginative outlet, accompanied by revealing and resolving characteristics. Vivid dreams would be a response from the poet's unconscious who, in an attempt to apply the compensatory and prospective function, will combine the subjective and objective level of the dream theory of the Jungian school. What has been said will be amply demonstrated in the analysis of the texts of ours and in a fundamental traumatic event in Blake's life: the premature death of his brother and protégé Robert. In fact, following this traumatic event, the 'visions' will become constants within the author's life, they will acquire new strength and a significantly more complex symbolism given the extent of the trauma and the strenuous attempt of the subconscious to compensate for what happened. All this has provided a new and interesting interpretation of its symbolism, allowing us to travel inside not only the Blakean mythology, but the tormented and turbulent soul of the same author, revealing it for what it really was: a child-angel and his journey, not only within a visionary universe wrapped in the delicate and deceptive dream veil, but also of his psychological rebirth that will make Blake nothing more than the embodiment of his own irrepressible imagination.

Note:

[1] http://www.dreamscience.ca/en/documents/New%20content/lucid%20dreaming%20pdfs/vanEeden_PSPR_26_1-12_1913.pdf , P. 11

[2] Lucid Dreaming as a Marker of the Evolution of Consciousness, Jeremy Taylor, Jung Society of Atlanta, p. 1 (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JptC1FezeElM8Xd4QbkJ42sXEeJ6syRZ/view?ts=5e2038b6)

[3] Structure and dynamics of the psyche, Carl Gustav Jung, 1967, vol. 8 par. 505 p. 243

[4] Jung's Dream Theory, Kelly Bulkley, p. 2 (http://www.dreamresearch.ca/pdf/jung.pdf)

[5] Ivi

[6] Lucid Dreaming as a Marker of the Evolution of Consciousness, Jeremy Taylor, Jung Society of Atlanta, p. 1

[7] Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, General Books LLC, Memphis, USA, 2012. p. 30

[8] Ibid, p. 9

[9] Ibid, p. 7

[10] Lucid Dreaming as a Marker of the Evolution of Consciousness, Jeremy Taylor, Jung Society of Atlanta, p. 1 (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JptC1FezeElM8Xd4QbkJ42sXEeJ6syRZ/view?ts=5e2038b6)

[11] https://sleepcouncil.org.uk/sleep-hub/vivid-dreams/

[12] https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/how-trauma-can-affect-your-dreams

[13] https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/284378.php#causes

[14] GE Bentley Jr., William Blake: The Critical Heritage, P. 36

[15] Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, General Books LLC, Memphis, USA, 2012. p. 10

[16] Ivi

[17] GE Bentley Jr., William Blake: The Critical Heritage , P. 37

[18] Ivi

[19] Jung's Dream Theory, Kelly Bulkley, p. 2 (http://www.dreamresearch.ca/pdf/jung.pdf)

[20] Ivi

[21] Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, General Books LLC, Memphis, USA, 2012. p. 7

[22] Ibid, p. 23

[23] Ivi

[24] Ivi

[25] Osbert Burdett, William Blake, Parkstone International, 2012. p. 47

[26] Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, General Books LLC, Memphis, USA, 2012. p. 25

[27] Jung's Dream Theory, Kelly Bulkley, p. 2 (http://www.dreamresearch.ca/pdf/jung.pdf)

[28] Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, General Books LLC, Memphis, USA, 2012. p. 26

A comment on "William Blake: sacred visions and "Lucid Dreaming""