Unknown in life, Edgar Allan Poe saw his genius fully recognized only after his untimely death, as happened later also for HP Lovecraft, who followed in his footsteps: today, almost two centuries after his death, Poe is considered an author more unique than rare in narrating the unusual, in exploring the greatest and atavistic terrors of man, in recalling the lost beauties of ancestral times.

di Jari Padoan

originally published on CentroStudiLaRuna

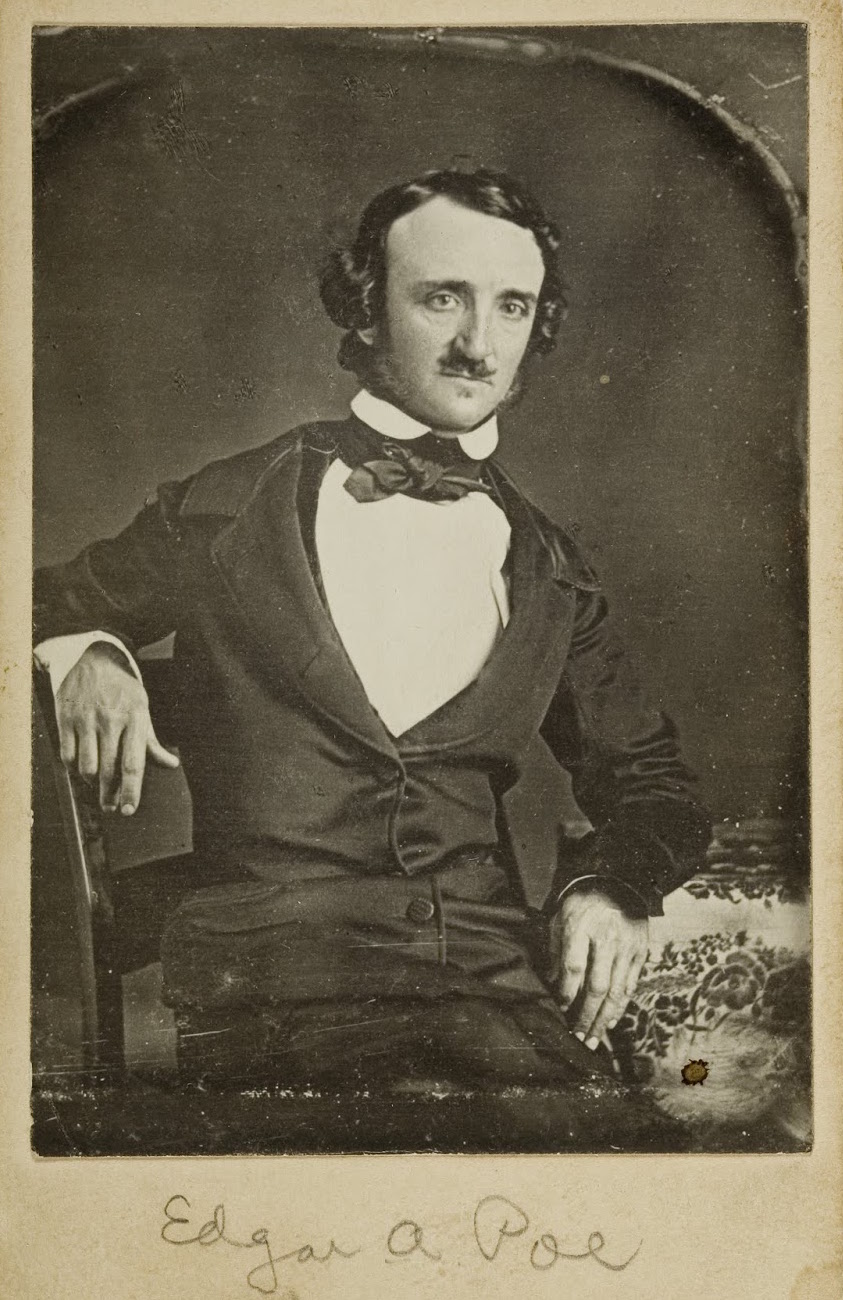

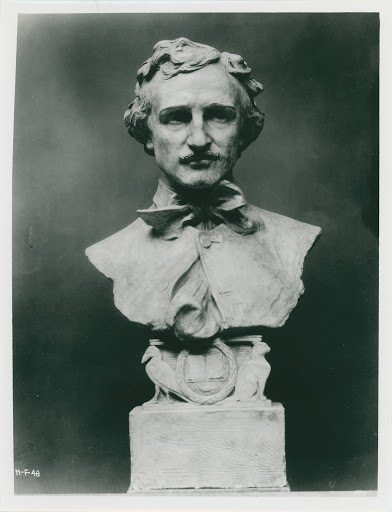

cover: portrait of EA Poe, 1849, preserved in J. Paul Getty Museum

It is surprising how the work of a now legendary author like Edgar Allan Poe (born in Boston on January 19, 1809 and died in Baltimore at the age of forty), a writer among the greatest in American literature but above all a tormented figure of intellectual and dreamer, has continued for almost two centuries to reveal symbolic values of such depth as can be only that of great literature.

First of all, EA Poe was a man of the nineteenth century, a crucial century of the long (involutionary) path of the modern era, so particularly immersed in the tormented cultural conflict between the unstoppable path of positivist thought on the one hand, and the sentimental chasms of romantic and decadent culture on the other. He was therefore a journalist, a man of letters with a far from ordinary acumen (it is not so well known that Poe reviewed an English translation of The Promessi Sposi by Manzoni, in his magazine Southern Literary Messenger in May 1835), as well as an unstable and hypersensitive soul, an old-fashioned gentleman torn apart by the demon of alcoholism that will take him to the grave, a genius very far from the modern and "barbaric" America in which he was born.

It is impossible, in a brief memory of a few lines, to try to define the complex figure ofEdgar Allan Poe man and writer, still today mostly famous as a "storyteller of terror" and pioneer ofhorror contemporary, and not, as widely recognized by the most disparate critics and enthusiasts, author more unique than rare in narrating the unusual, in exploring the greatest and atavistic terrors of man, in recalling lost beauties of ancestral times.

With all due respect to Harold Bloom, somewhat reluctant to put Poe's name in his The Western Canon (1994), it would be enough to remember that already in the decade following his death were the great French poets such as Charles Baudelaire and Stéphan Mallarmé, standard bearers of symbolism and modern poetry, enthusiastically promoting the validity and power of the Bostonian's work in Europe.

The influence that Poe exerted on later Western literature is profound and unavoidable, comparable perhaps only to that of giants such as Dostoevsky, Hugo, Proust, Kafka or the aforementioned Baudelaire. In the context of fiction, entire literary genres such as the fantastic and the modern detective (from Poe practically invented with the famous The Murders in the Rue Morgue, the main inspiration of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes), will no longer be the same after the publication of his short stories and novel The Adventures of Arthur Gordon Pym.

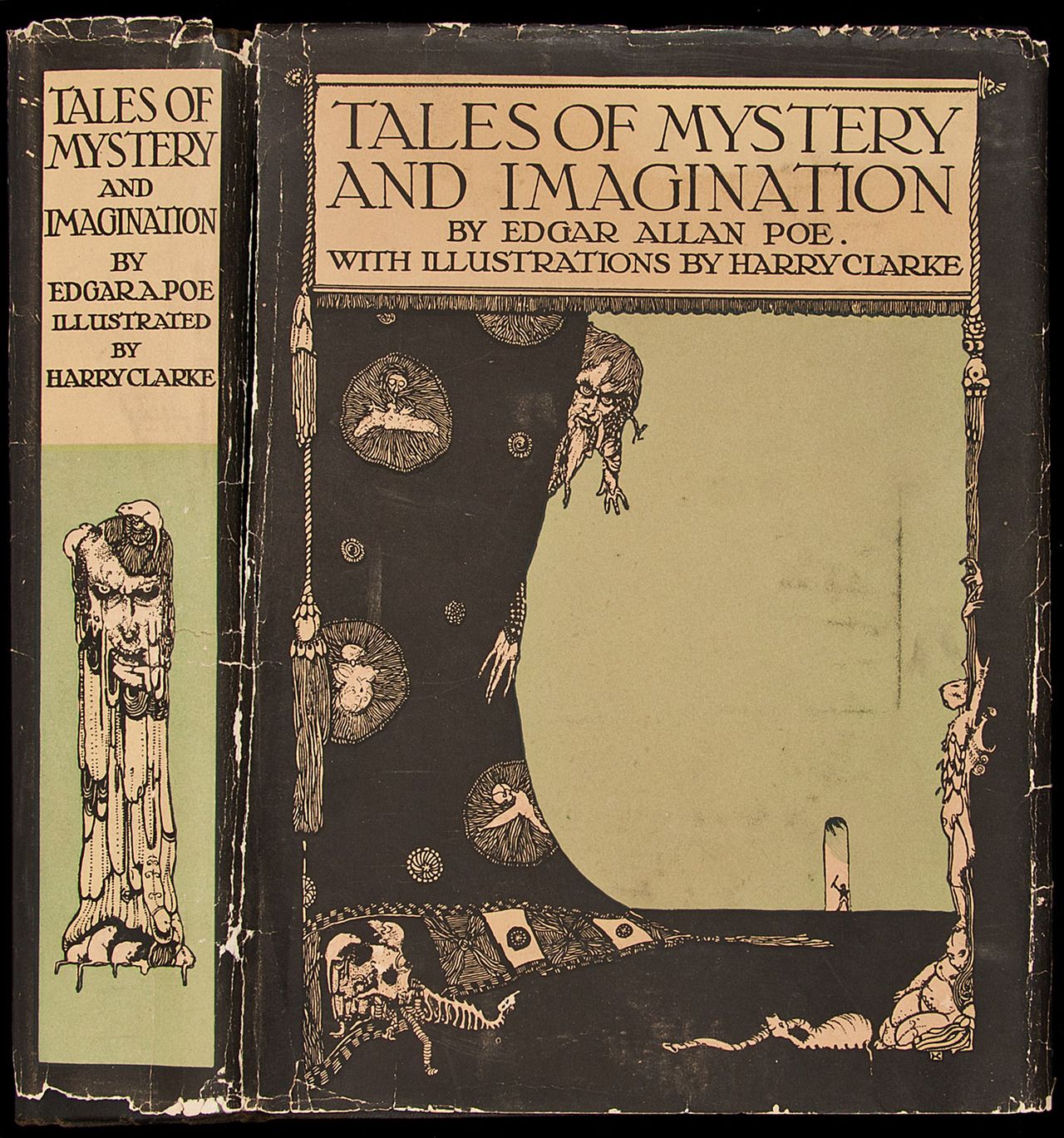

Starting from the surreal and dark oneirism in the wake of ETA Hoffmann and Charles Nodier (and who will return, also thanks to the influence of Poe, in Nerval, Gautier, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam...) the dark and bizarre events narrated in the Tales of Horror and Imagination, published in the XNUMXs, rework the stylistic features of the ghost story and gothic novel, quickly entering the collective imagination. This vast influence, both in the nineteenth century and in the following, is amply testified by the work of countless great authors of fantastic fiction and beyond (first of all Verne and Lovecraft, without forgetting the profound reception of Poe by Italian literature: from the Milanese Scapigliatura of Prague and Tarchetti to Giovanni Pascoli), from cinema and comics.

But if in the most famous Such by Poe we are guided through the gloomy meanders of the nightmare until we cross the borders of the unknown land from which no traveler returns, and his proto-science fiction tales such as Mellonta Tauta they weave disturbing and disillusioned (as well as very topical) reflections on the degeneration of science and modern society, it is also and above all in his great poetry that the American writer reveals a lyrical, "classic" and "romantic" breath in the highest sense of these terms, which fascinates and amazes.

Despite being born on American soil, Poe boasted Scotch-Irish origins and spent the years of first education in a college in England (on the initiative of the adoptive family, the Allans); it is therefore not surprising to note the deep ideal bond that the writer always maintained with the Old World, with its archetypes and traditions, and that the sensitive and attentive reader cannot fail to perceive in his literary style.

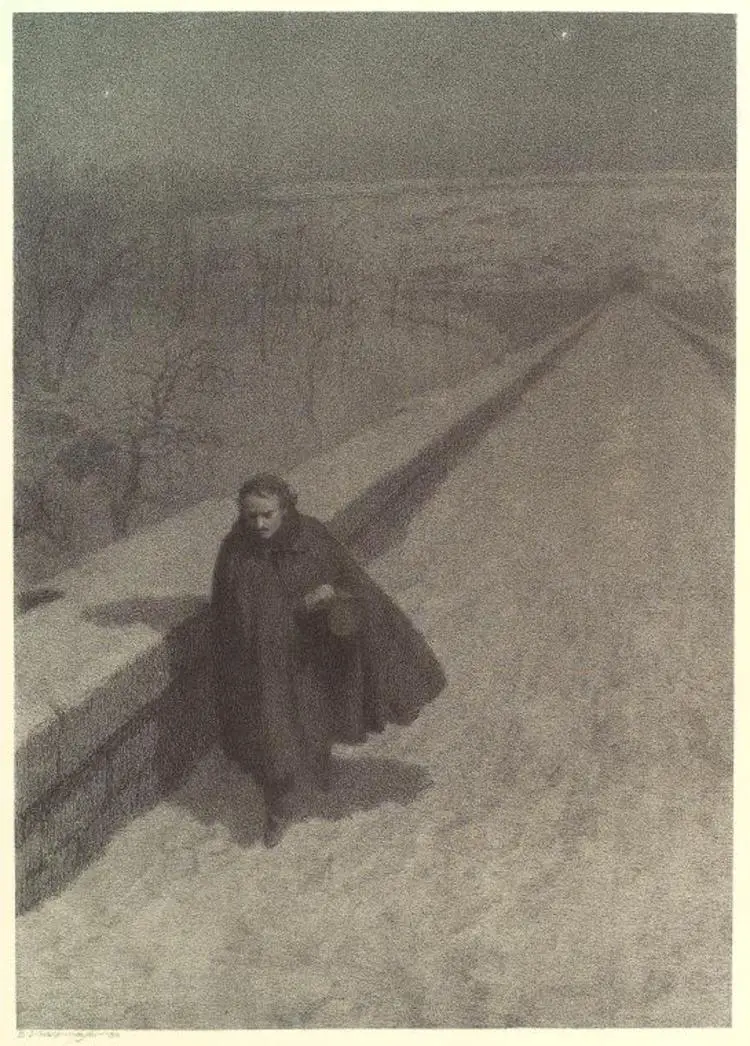

From ethereal and hazy images of a classical, oriental and medieval-romantic setting (although perhaps more similar to the shadows of Gothic novel that to the ancient chivalric novel) that populate Poe's interior scenario, and that he stages through metric constructions among the most refined and musical of the English poetry of the time, emerges an ineffable nostalgia for the ideal and the sublime, a perennial search for beauty, albeit always lapped by the threatening shadows of decadence and death.

Think of lyrics as the dismal masterpiece Ulalume (with its "ashen and sad skies", the "withered and withered leaves" in the night of the "lonely October" ...) to the anguished The Conqueror Worm, to the dark and poignant The Sleeper, To cosmic melancholy that penetrates the dreamers Al Aaraaf, To Helen, Israel, Annabel lee, Evening Star, A dream within a dream. And of course to his most famous poem, later Tamerlane e The Bellsor rather that The Raven published in 1845, in which Poe evokes the nocturnal entrance of the "grim crow" who, in the epic version of Mario Praz, it came from the "plutonium kingdom of shadow" to put its grim seal on the despair of the ego.

And it is no coincidence that just The Raven it was the writer's last major hit shortly before his own tragic disappearance: the piece, at the center of Poe's lyrical imaginary which, as it is explained in his Philosophy of Composition (famous manifesto that reveals all the solid theoretical and metric preparation of the poet) raises to the nth degree the eternal reason for the loss of the beloved, it is important and representative to understand many things of his work, and with it of his soul.

The bird, mysteriously announced in the first lines by tapping on the door of the room and then making its fluttering entrance, is "A majestic crow of ancient holy times" (as expressed by another happy translation by Tiziano Sclavi which can be read in n.33 of Dylan Dog, «Jekyll!»): Like so many other images that recur in Poe's writings, that crow comes directly from the time of the Myth. He crosses the Plutonia banks of the Night to go and perch, with a pompous and haughty manner, on the crest of Athena, as if to represent the darkness of the unconscious that takes over the forces of reason, darkened by despair and terror of the unknown.

But this rather obvious, as well as apparently negative, reading of the symbol chosen by Poe is not the only possible one. The image of the crow, a very powerful archetype, is encountered in various ancient traditions: it is among the most typical psychopomp animals, together with the dog, the jackal, the wolf; and just like the wolf (in whose name, not surprisingly, we find the Indo-European root lyk, the same as luxury), his figure so typically inherent in darkness can be at the same time that of a mysterious bearer of light and knowledge. Just think of Hugin and Mugin, the Thought and I remember, the two ravens who follow Odin according to Norse mythology. And in the labyrinths of the alchemical tradition, images such as that of dragon, of the skull and the raven constitute the symbolism linked to Nigredo, to the impenetrable and unknown abysses of the Interior Terrae, which only if faced and crossed will allow to go back to the light of the Great Work.

Those abysses are the same ones represented by the crumbling corridors of the Usher House, from the disturbing apparitions of Ligeia or from the inconceivable terrors that open wide in the ocean expanses in which Gordon Pym ventures. Those abysses from which, unfortunately, Edgar Allan Poe could no longer re-emerge («… And my soul from out that shadow that is floating on the floor / Shall be lifted / Nevermore ... "), after having personally visited them in his sad existential parable and having portrayed them in his works, leaving a mark in world literature far beyond the confines of that too soon dissipated life of his.

A life that, as he himself wrote, platonically, is none other than «a dream within a dream».

18 comments on “Edgar Allan Poe, singer of the abyss"