Thanks to Bietti editions, "The metamorphosis of blood", a spiritual autobiography of Gustav Meyrink, an Austrian writer of the early twentieth century, whose literary mythopoiesis was influenced by his esoteric and occult studies, is an ideal continuation of the collection of essays "At the frontiers of the occult”Recently published by Arktos editions.

di Marco Maculotti

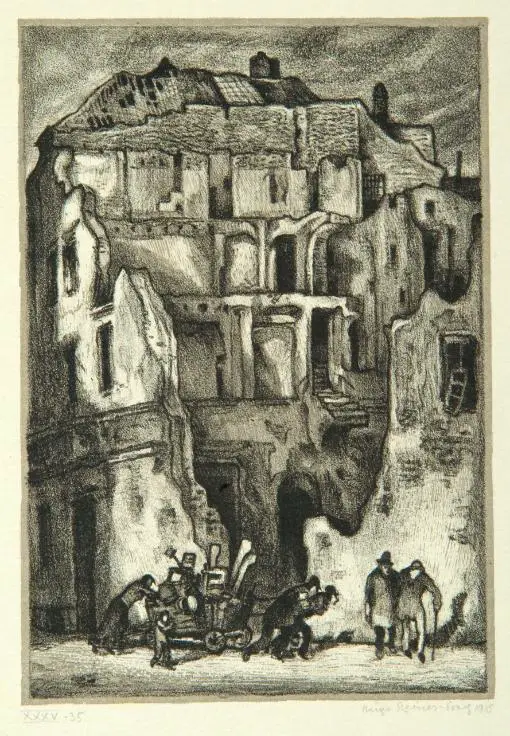

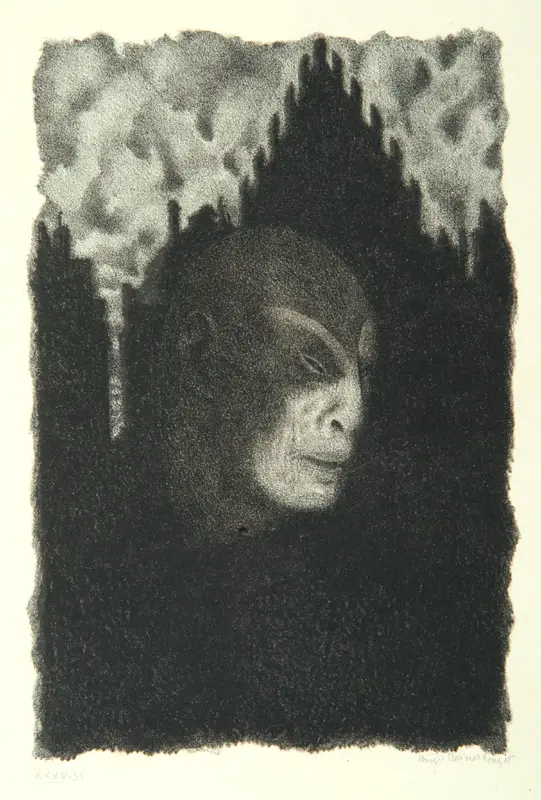

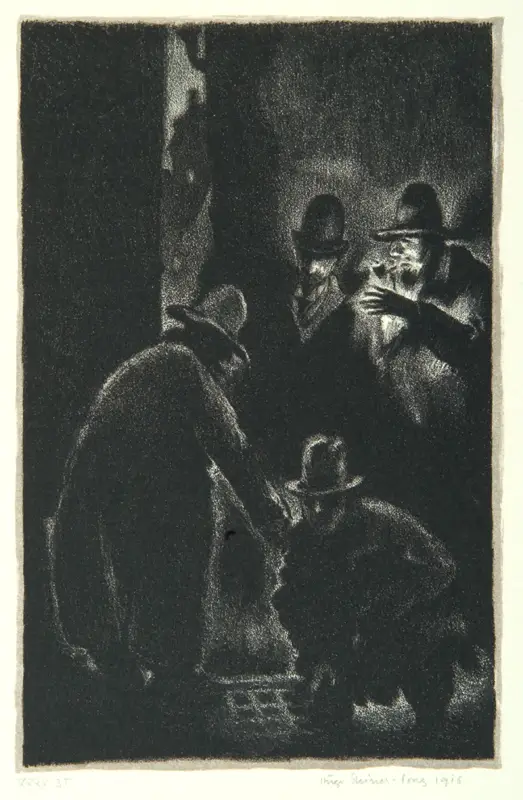

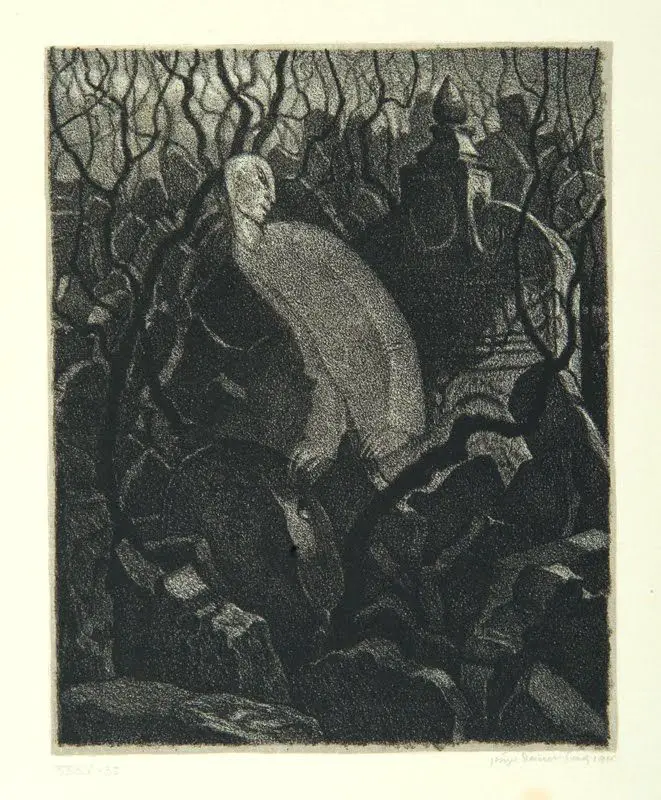

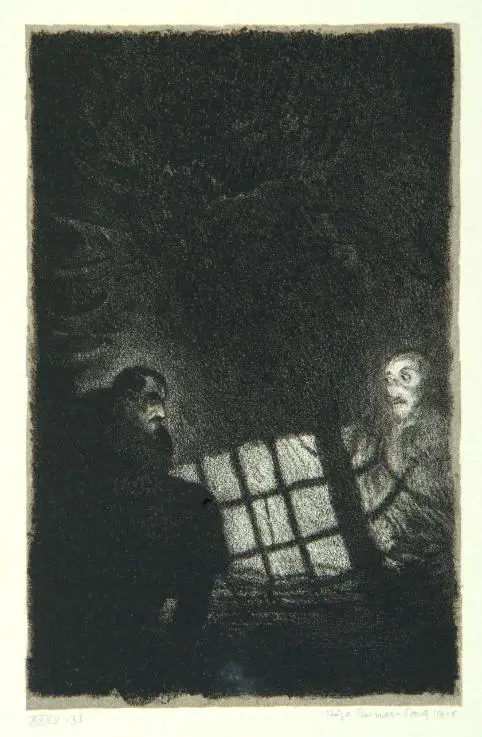

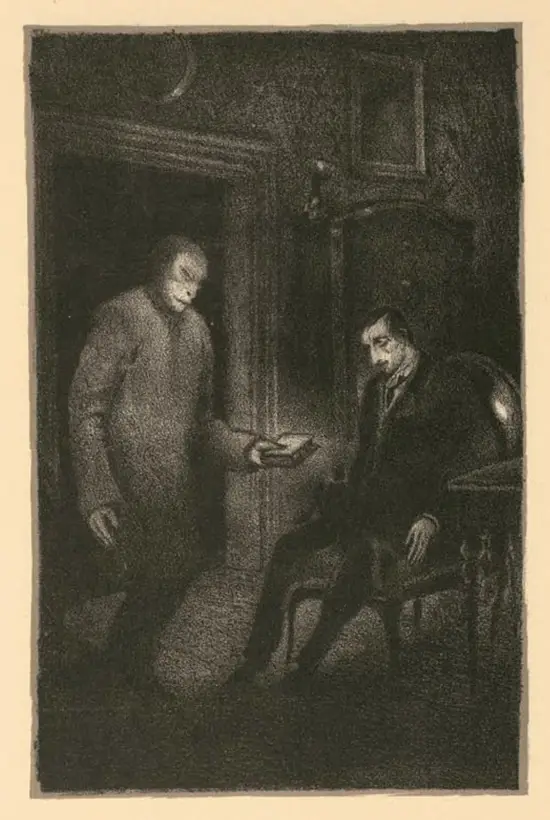

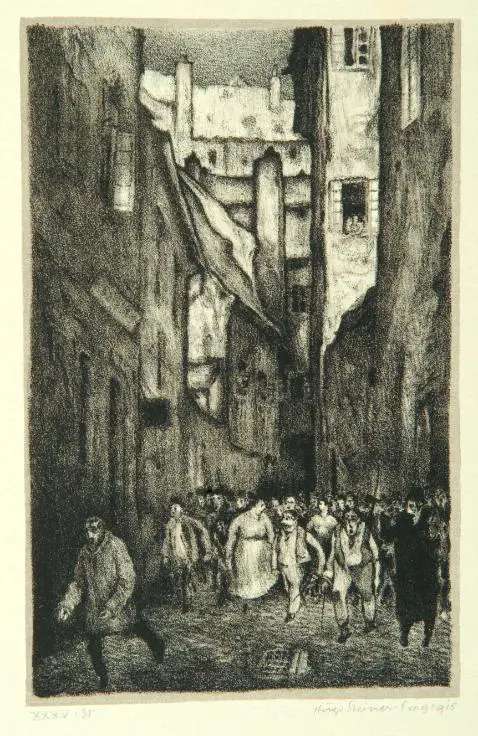

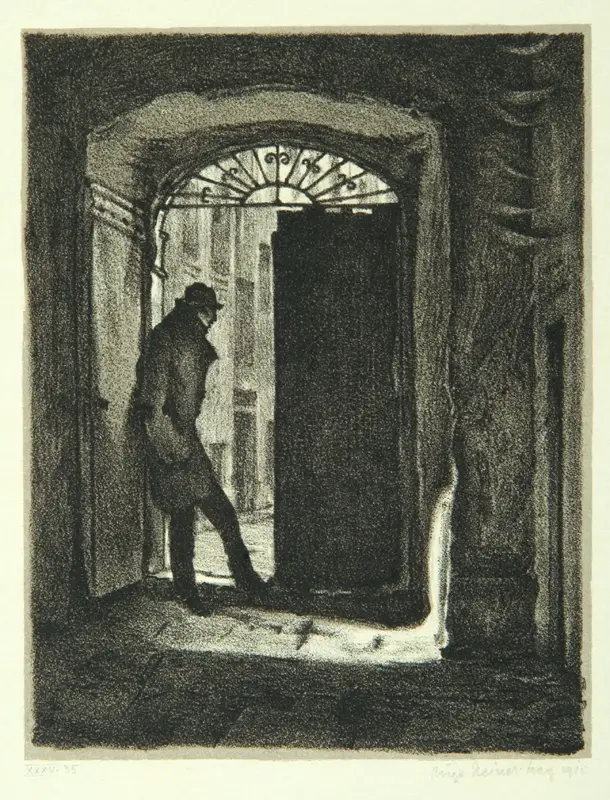

cover: Hugo Steiner-Prag, illustration for Meyrink's “Der Golem”, 1915

"When the earthly man closes his eyes, the spiritual one opens them, and vice versa." [1]

"... if you come to the gushing spring from where all things are born, then you will be free and you will be able to let the stars of your destiny come out of their orbits". [2]

«… A perennial glow beyond the threshold of awareness:“ I don't die, death is nothing but an empty ghost ”. [3]

Di Gustav Meyrink we have already spoken on our pages, reviewing his collection of essays At the frontiers of the occult - Esoteric writings (1907 - 1952) recently translated into Italian by Arktos editions. The metamorphosis of the blood (original title Die Verwandlung Blutes), a text just published by Bietti editions - which in the subtitle invites us to consider it as a "Spiritual autobiography»Of the Austrian writer -, is to be framed from the same perspective, presenting in the form of an essay the“ occult ”themes that have made the mythopoiesis of the author in question so unique.

This novelty of the Bietti catalog, addressed to fans of Central European literature of a "supernatural" character of the early 900s and to scholars of "esoteric" doctrines, is embellished with a preface by Sebastiano Fusco (Heaven in the shadow of swords. Esotericism in Meyrink's work), from the rare introduction by Enrico Rocca to the first Italian edition of The Golem and from the critical afterword by Andrea Scarabelli (Magical metamorphosis), to whom the curation of the text must also be ascribed. This is how the work on the back cover is presented:

"As now universally recognized, Gustav Meyrink has gone down in history for having included, in his novels and short stories, a series of first-hand experiences in the most varied areas of what we usually call"esotericism". All these experiences - from Yoga to alchemy, from tantrism to theosophy - are carefully documented The metamorphosis of the blood, autobiographical essay that remained unpublished at the author's death, dating back to the last years of his life and here translated for the first time into Italian. Spiritual testament, long reverie on the role of destiny and the possibility of actively influencing it, hymn toCreative imagination, this writing can be considered a sort of "laboratory" of the fiction of Meyrink, Demiurge of the Fantastic who made life, literature and occultism just one thing".

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

Speaking of transmutation of blood or body - doctrine that the author finds both in Yoga and in the ancient Gnostic teachings, which among the Rosicrucians - Meyrink underlined how the overcoming the purely human condition followed by the mystical experience of union with the divine provides for the transmutation of the same bodily vehicle as the neophyte: a theme that he himself investigated in his initiatory novels, as did the Welsh in the same period. Arthur Machen [4].

In the latter's stories, the characters who mysteriously manage to access theAnother world they will realize, once they return to our world, that they no longer have anything in common with it, belonging by now de facto al invisible world. The change that occurred in these people after the visit to fairy land it is not merely psychological, but also ontological: both their body and their soul undergo a real transformation, operated by Fairies themselves, which closely resembles the "ritual dismembermentPerformed by the initiating spirits in the shamanic traditions and the consequent transmutation carried out by the latter on the body of the neophyte [5].

Recalling this doctrine, Meyrink supported the idea that "the soul does not live in the body to abandon it, as if it were in a whose de sac, but to transform matter» [6]:

"It is a question of finding a form that is not a prison, like the common human body subjected to the elements, but is similar to what the New Testament calls"resurrected body"". [7]

In short, it would be a question of reviving what some Gnostic sects called the "Heavenly AdamAnd which others called "the body that is not Adam's", or the "body of light". For the change to take place, which occurs both internally and externally, "something must come from above" [8]: central is in Meyrink's vision the importance given to Daimon di platonic memory, to which he referred with the phrase "the Veiled", to the point of coming to consider his life "as an action exercised by an invisible entity" [9]. “The only real key to happiness, well-being, health and things like that is union with the veiled; in everyday life, it manifests itself as the providence that helps us when we need it most " [10]; which is why it is essential "learn to understand the will of the "veiled" when he disposes of destiny» [11].

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

In the transcendental union with the Veiled Meyrink identified the very secret of Yoga, noting that "it is not a link with God, but with something very" similar to God ", so to speak, with What each one should be, with What each really does è unknowingly, blinded and crippled by schizophrenia» [12]. Insights that Meyrink wrote at the end of the XNUMXs and that seem to echo those of the Irish counterpart WB Yeats in anima mundi and The Vision, as well as anticipate those closest to us by Giorgio Colli (Greek wisdom) And james hillman (The code of the soul):

"I want to use a metaphor: the inner man hidden, separated from us, who is alien to us, stranger (!) in waking consciousness, the veiled, in a sense, lies within us vertically; is the spinal cord - the Sushumma - which Yoga is about. The outer man is separate, "oblique" with respect to it! That's why the two don't match! For the man who "breathes" left and right, the inner one is an invisible stranger, not even sentient [...] each person, in fact, is "sick" and consciously split in a different way». [13]

Union with the "inner man" in the doctrine of the Meyrenkian Awakening opens wide to the human being a new deeper reality existing behind it superficial screen of appearance: Andrea Scarabelli on the other hand cites Serge Hutin who defined the literary works of the Austrian writer "key books"Behind which they stand out"great magical secrets thanks to which the predestined man could escape the web of sensible appearances and finally contemplate the true one, the only one Reality» [14] - in this approaching once again to Do.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

In the stories of the Welsh author no less than in those of Meyrink the "vision of reality»Of the protagonists is influenced by certain mythical elements to the point of completely overturning: suddenly, following the experiences lived inAnother world, the everyday world appears unreal, emptied of any higher meaning. The scaffolding that supports the structure of reality suddenly collapses, revealing an underlying level that was previously unknown to exist: the Other World thus becomes the only true reality, while the so-called real world degenerates into mere theatrical representation, staged and senselessly held upright by a mass of puppets lacking a profound vision of existence [15]. Mirror Meyrink wrote:

«If the life after death that mediums describe to us is objectively unreal, equally unreal is everything that appears to us on Earth. One is as much a hallucination as the other». [16]

However, unlike Machen, the secret Reality that lets itself be glimpsed among the meshes of the narrative skeletons that make up the Meyrenkian work (think of The green face, or a The Golem) - as Scarabelli points out - is not "located in some hidden" afterlife ", but located in the beating heart of the world we all know, access to which does not require mystical suspensions of consciousness or other bizarre of this type but un active change of gaze» [17]. It is not, underlines Joseph Strelka, «a romantic escape in the face of reality but a deep penetration of reality by the spirit and a spiritualization of the body» [18]; and Scarabelli concludes by noting how the development of what we could define consciousness daimonic "It does not imply an abstraction, a distancing from the things of the world, but rather a rooting in them" [19].

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

On this theme, some passages of these two essays by Meyrink seem to echo certain doctrines apparently paradoxical of the Mahāyāna Buddhism, such as the one that states the transcendental identity between Nirvana and Samsara. In the opening words of Immortality, the Austrian writer begins:

"If I had to answer the question:" Is there any kind of immortality? ", It would be:"There is absolutely nothing outside of immortality". Life and immortality are the same. What the common man means - or thinks he means - when speaking of "death" does not exist. If there were such a "death", life would have already sunk into it for a very long time, without re-emerging from that Nothingness ». [20]

And elsewhere he states:

«The present is elusive to all beings on Earth, because they do not live in reality. If they were able to feel the present, they would have access to eternity, since the present is nothing but eternity, in which there is true life.». [21]

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

With these premises it must be said, as Sebastiano Fusco explains in the preface, that Meyrink meant death more than as "the experience of final dissolution", as a "springboard to higher existence", and referring to the ancient sacred doctrines he believed that it was "only by an act of faith that, after death, we access life in some way. According to the traditions, this process is not automatic, but must be conquered. In short, we must train ourselves in this life a transform the experience of death into something constructive» [22].

To this we must add that, consistently with the Platonic doctrine ofanamnesi, for Meyrink knowing is the same as remembering: to the finally awakened individual, who finally knows the profound structure of the Real not by having learned it but by having revived it in his own blood memory,

«what until then had appeared to him as death would turn out to be appearance; separated by oblivion, the links of consciousness would rejoin once again in a single chain; forms would come back to light, nothing but forms; would come the Judgment Day, when the sleepers will rise from their graves ». [23]

It is not, of course, an easy way and free of risks and dangers: neophytes who have not dutifully purified themselves before Awakening and the consequent encounter with the Veiled to go towards madness, if not death [24]. Fusco relates this appearance tremendous of the mysterium religious tourism [25] with the call, taken from a story by Meyrink, to one secret word guarded by the monks of a Central Asian monastery: "A word so terrible that anyone who hears it, listens to it or hears its sound suddenly turns into jelly" [26].

Even in this case, it is impossible not to underline the parallelism with Machen: in two of his first published works, The Great God Pan e The inner light, the meeting of the negligent protagonists with the divine-demonic-panic epiphany leads them inextricably to damnation, and their bodies subjected to the process of "protoplasmic regressionThey manifest a total loss of control over their own form, to finally liquefy into a sort of magmatic matter devoid of any defined and describable form. Conversely, as Fusco points out, Walpurgis night by Meyrink is:

«an image of chaos, of dissolution. Whoever finds himself in the chaos of the Walpurgis Night loses his individuality: he shatters, is reduced to surviving only through a series of repetitive acts, he automates himself. It is the image of the society in which we live today […] a chilling consideration, if we consider that the eternal repetition of the same sin is, traditionally, one of the images of hell ». [27]

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

In any case, to empirically confirm the risks inherent in the encounter with the Veiled, it is of great interest due to its singularity what Scarabelli reported regarding the crisis of the twenty-third year of age which interested, in addition to Meyrink, also three other intellectuals who lived in his own era, and that Massimo Scaligero, in an article published in 1934 dedicated to the fiction of the Austrian writer, approached the aforementioned: it is Otto Weininger, author of Sex and character, by the philosopher from Gorizia Carl Michelstaedter and magical idealist Julius Evola [28]. Scarabelli notes that, curiously:

«All these authors were united by a singular fate linked to the twenty-third year of age, which for two of them it was fatal, while for the others it marked the beginning of an inner rebirth. Michelstaedter and Weininger committed suicide, both twenty-three, in 1910 and 1903. If at that age, in 1891, Meyrink came close to suicide, the same happened to Evola, who, having returned to Rome after a brief war experience, following the use of hallucinogenic substances […] experienced a very profound crisis ». [29]

And if Meyrink deposited the revolver after eyeing a leaflet on which the title stood out in large letters "On life after death" that someone, at that fatal moment, had providentially slipped under the door of his house, Evola said that the extreme gesture was avoided thanks to a sort of "enlightenment" that he experienced in reading a text of the early Buddhism. The speech the Baron refers to focuses on a series of bonds that the "noble son" must dissolve in order to reach Awakening:

«He will have to stop identifying" with his own body, with his feelings, with the elements, with nature, with divinity, with everything, and so on, higher and higher, towards absolute transcendence ". Until reaching the last term, theextinction, about which the young Evola reads: "Whoever takes extinction as extinction and, taking extinction as extinction, thinks of extinction, thinks 'mine is extinction' and rejoices in extinction, he, I say, does not know extinction"». [30]

Note:

[1] G. Meyrink, The metamorphosis of the blood, Bietti, Milan 2020, p. 78

[2] Ibid, pp. 147-148

[3] Ibid, p. 42

[4] See M. Maculotti, The fairies, the witches and the door to the Other World: folkloric and ethnographic reliefs on the work of Arthur Machen, in Zothique n. 4 year 2020, pp. 181-126

[5] See M. Eliade, Shamanism and the techniques of ecstasy, Mediterranee, Rome 2016

[6] Meyrink, Metamorphosis, P. 63

[7] Ibid, p. 127

[8] Ibid, p. 60

[9] Ibid, p. 72

[10] Ibid, p. 98

[11] Ibid, p. 111

[12] Ibid, p. 75

[13] Ibid, pp. 95-96

[14] A. Scarabelli, Magical metamorphosis, afterword to Meyrink, Metamorphosis, P. 141

[15] Maculotti, op. cit.

[16] G. Meyrink, The invisible world, cit. in Scarabelli, op. cit., p. 145

[17] Scarabelli, op. cit., p. 141

[18] Ibid, pp. 141-142

[19] Ibid, p. 148

[20] Meyrink, op. cit., p. 123

[21] G. Meyrink, The alchemist's house, cit. in Scarabelli, op. cit., p. 150

[22] S. Fusco, preface to Meyrink, Metamorphosis, P. 17

[23] Ibid. p. 125

[24] Meyrink, Metamorphosis, pp. 74-75 and 97

[25] See R. Otto, The Sacred, SE, Milan 2009

[26] Fusco, op. cit., pp. 10-11

[27] Ibid, p. 14

[28] Who among other things, as Scarabelli recalls, was a translator of Meyrink and Weininger, as well as one of the first in Italy to speak of Michelstaedter; the philosophical conceptions of the latter are also more recently taken up by Thomas Ligotti in the essay The conspiracy against the human race (Il Saggiatore, Milan 2016).

[29] Scarabelli, op. cit., p. 133. In this regard, cf. J. Evola, The path of cinnabar, Mediterranee, Rome 2018, pp. 53-54

[30] Ibid, p. 134

A REALLY NICE ITEM. THANK YOU

Thanks to you!