The new special issue of zothique, magazine of fantastic and "weird" literature published by Dagon Press, in its over 230 pages allows us to retrace the life and work of Arthur Machen, a Welsh writer who between the end of the XNUMXth century and the beginning of the XNUMXth was able to look beyond the "veil of reality" and reveal the essence of "Great God Pan“, Establishing himself as one of the greatest authors of supernatural fiction of his time.

di Lorenzo Pennacchi

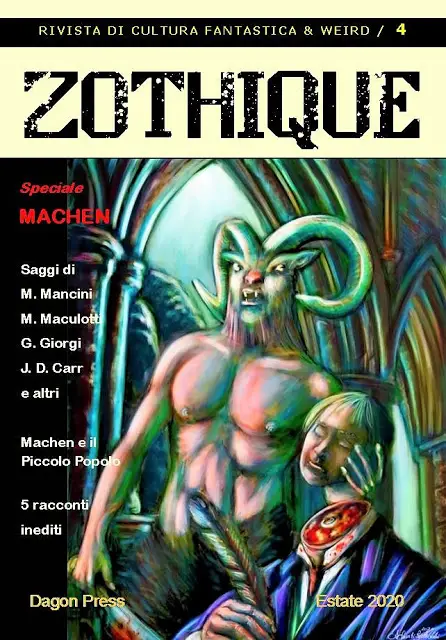

cover: Arthur Machen seen by Andrea Bonazzi

«Man is created mystery by mysteries and visions. "

- Arthur Machen

The fourth number of zothique, magazine of fantastic & weird literature published by Dagon Press, released in July, is entirely dedicated to Arthur Machen, a Welsh writer who for more than a century has revealed the essence of great god Pan to thousands of readers. The cover of Adriano Monti Buzzetti immediately introduces us to the uncanny Machenian universe. In his 1919 essay, Das Unheimliche, Sigmund Freud, inspired by the insights of his colleague Ernst Jentsch, investigated the nature of this layer of psychic life:

«There is no doubt that it belongs to the sphere of the frightening, of what generates anguish and horror, and it is equally certain that this term is not always used in a clearly definable sense, so much so that it almost always coincides with what is generically distressing. However, it is reasonable to expect that there is a particular nucleus, which justifies the use of a particular conceptual terminology » [1]

Nonetheless, well before Freudian research and over a decade later, Machen probed this sentiment far and wide, leading his audience into that nucleus that the Austrian psychoanalyst had only sketched out. This full-bodied volume, as per usual cared for with great passion and professionalism by Peter Guarriello, organically reconstructs this experience, through numerous critical contributions and five short stories (including four by the Welsh writer) that have remained unpublished in Italy until now.

The very large essay by Matthew Mancini (Arthur Machen. Beyond the Veil of the Unknown), at the opening of the register, offers a detailed portrait of this indomitable seeker of hidden truths, in which life and work are tangibly related:

« He was a character who repudiated materialism, completely disinterested in money and material things, suspicious of the usefulness of scientific progress, being anchored to spiritual values that led him to regress to the glories of an ancient past, in a crossroads of cultures between paganism and Christianity, passing from Romanesque to Celtic traditions, to be more interested in the things of the other world - the one to which the occultists refer - than in those of the world that marks the rhythms and determines the choices life of most people » [2]

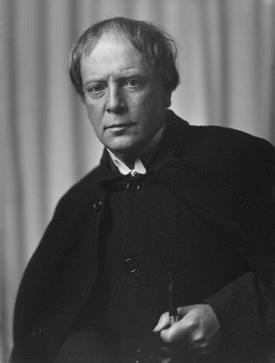

Arthur Llewelyn Jones was born in Caerleon-on-Usk March 3, 1863, son of the Anglican pastor John Edward Jones and the Scotsman Janet Robina Machen, from whom he will take the surname. In his memoirs of him he remarked how his greatest fortune was that of being born in the heart of Gwent, in a real kaleidoscope of legends [3].

Within his admirable study included in the second part of the register (pp. 181-222), The fairies, the witches and the door to the Other World: folkloric and ethnographic reliefs on the work of Arthur Machen, Marco Maculotti remember how already Jorge Luis Borges had taken over the fair Celtic identity of Machen, through which "he could feel darkly victorious and ancient, rooted in his own land and nourished by primitive magical sciences" [4]. Caerleon, Isca Silurum for the Romans, it is also identified with Camelot, the fortress of King Arthur. Finally, it is one of the lands most affected by the tradition of the fairies, the enigmatic creatures that inhabit the Secret kingdom, exquisitely outlined by the Scottish Presbyterian Robert Kirk at the end of the seventeenth century (The Secret Commonwealth, written in 1692 and first published only in 1815).

In Machenian work, however, there is on several occasions a radical reversal of the post-Shakespearean perception of these beings, as the Welsh author, a passionate scholar of Celtic folklore, recovered the traditional and disturbing vision of the so-called "little people". Neither The story of the black seal, Professor Gregg, the author's alter ego, seems to refer directly to Kirk when he states: "Just as our ancestors had called terrible beings" fairies "or" good "because they feared them, they had also clothed them with fascinating forms, knowing full well that the truth was very different", reaching the conclusion that fairies and devils would be of one race and one origin [5].

The young Arthur, shy and not very sociable, spent his youth without the comforts of a loner bohemian, immersed in the great classics, in the stories of Edgar allan Poe, in the volumes of alchemy, mythology and history, developing an archaic and strongly anti-commercial style of writing. In 1887 he married Amelia Hogg, a music teacher who was well integrated in literary circles. It was in these years that, alongside his work as a translator, he began writing for various newspapers, meeting several important personalities, such as the occultist Arthur Edward Wait it's a Oscar Savage at the height of his success, which he attended in the summer of 1890. Only a few years later, in '95, Wilde was imprisoned for homosexuality, scandalizing English society and negatively impacting the authors around him [6].

In any case, Machen put his own in it. The Great God Pan, first serialized in the magazine Whirlwind in 1890 and then in its final form in '94, it was reviewed in this way by Manchester guardian: "The most despicable novel ever written in English. It is deliberately, with a sharp impiety. We could say more, but we don't want to advertise this cursed book " [7]. Although similar reviews also came from other newspapers [8], the work traced the main road of Machen and crossed national borders, so much so that the symbolist poet Paul Jean toilet he was delighted. As Mancini points out:

« By "God Pan" Machen does not trivially mean Baphomet in flesh and blood [...], but rather the fantastic world that extends beyond the transience of the everyday world. Pan is something immaterial, the beginning and the end of everything. He takes on an abstract value, a bit as if you wanted to make him symbolize absolute truth, that is, the secret of existence. » [9]

In Machenian mythopoeia, Maculotti writes, "Pan rises to the symbol of primordial Chaos and the primary agent of the process of regression to the preformal, an experience that is both ecstatic and terrifying» [10]. The protoplasmic regression, that denotes a different evolutionary line (detected by Jacques Bergier, quoted by Maculotti), is one of the main themes of the debut novel and is found several times in the work of the Welshman. Another central theme, originating from the story, is represented by the mystery of the world deserve it real, clouded by the sight of most. In one of the author's most famous passages, Dr. Raymond reveals to his assistant:

“I tell you that all these things are but dreams and shadows, the shadows that hide the real world from our eyes. There is a real world, but it lies beyond this enchantment and this hallucination, beyond these “hunting scenes on a tapestry, unbridled fantasies”, beyond them as on the other side of a veil. I don't know if any human being has ever lifted that veil. But I know, Clarke, that tonight you and I will see him lifted up in front of someone else's eyes. You will think this is bizarre nonsense. It may be bizarre, but it's real: the ancients knew what it means to lift the veil. They called it "seeing the god Pan" » [11]

The literary production continued briskly with two stages which, introducing the "little people" into the Machenian mythopoeia, played an extremely significant role in the Welsh author's fiction: The Three Impostors, a collection of stories related to each other, including the one already mentioned Novel of the Black Seal, published in installments between May and June 1895, in which the and gentle cosmetics other of these sinister beings emerges clearly, through one of the most disturbing descriptions ever [12]. But when things seem to be going professionally, Amelia is diagnosed with brain cancer in '99 and she dies within a few months:

“It's the darkest time in the Welsh. It staggers on the edge of sanity, like a log carried by the waves of the sea. When the irreparable is consumed, falls into a deep depression that tries to win in long walks, aimlessly, through the streets of London. » [13]

During this period, at the urgent invitation of his friend Waite, he became a member of the Golden Dawn, initiatory order in which they took part, among others, William Butler Yeats, Aleister Crowley e Algernon Blackwood. This experience is extensively retraced in this new book of zothique, in the contributions of George George e Leigh Blackmore, which highlight the different connotations. Certainly Machen was attracted to the aforementioned secret society and the possibility of finding satisfactory answers within it to the mysteries that fascinated him. In 1899 he wrote to the aforementioned Toulet:

“I am now convinced that there is nothing impossible on Earth. I just need to add, I suppose, that none of the experiences I have had have any connection with impostures such as spiritism and theosophy. But I believe that we live in a world of great mystery, of unsuspected and completely amazing things » [14]

What in the Bread and in other literary works of the late nineteenth century it had initially appeared as a entertainment literary, now seems to become without a doubt a real, tangible concern based on a very precise conception of the world and in strong controversy with scientism which was already the master at that time. In other words, Machen entered the Golden Dawn to understand these secret and invisible forces that exist behind the "veil of the real”And to try to dominate them. However, the attempt proved in vain, resulting again in a solipsist research, regardless of the initiatory hierarchy and aimed at what Machen himself was able to define "the great inner leap". As he recalled in 1925:

“Society as a society was real nonsense, based on useless and foolish 'Abracadabra'. She had absolutely no knowledge of anything, and hid the fact with absurd rituals and a high-sounding phraseology. She did not teach any true doctrine to those who were admitted » [15]

In Golden Dawn Machen came started with the name of Brother Avallaunius, a name that took from the composition The Garden of Avallaunius composed several years before and which will then find its complete form in prose in the novel The Hill of Dreams, written in 1897 and published only in 1907. Mancini considers this text a sort of watershed in Machenian production, the beginning of a new phase in which the author experimented as never before, and nevertheless in continuity with previous works .

After all, it is proposed again the theme of the self-seeking, summarized in the symbolic phrase of the philosophy of the protagonist Lucian: "Only in the garden of Avallaunius is it possible to discover the true and sublime science» [16]. On the same wavelength it arises The Secret Glory, a novel that engaged the author for over twenty years before being published in 1922. This text also witnessed the conversion to what we could define a "Celtic Christianity ", operated several years earlier at the suggestion of his second wife Dorothie, in order to cast out the inner demons that tormented him. Machen himself makes the young protagonist of this story, evidently one of his many literary alter egos, say:

“I was enraptured at the thought of those marvelous ones knights errant, of that Christianity which was not a moral code with some kind of metaphorical paradise offered as a reward for its dutiful observance, but a great mystical adventure in the mystery of holiness » [17]

Let's take a step back, because in 1904 Machen published in theHorlick Magazine The White People, one of his absolute masterpieces, perhaps the flagship of his stories about the "little people". A layered and chilling story unearthed in Green paper, preceded by a premise on the meaning of evil and of sin, whose essence would be embodied by a formula that, once encountered, will hardly leave the reader's memory: Take heaven by storm [18].

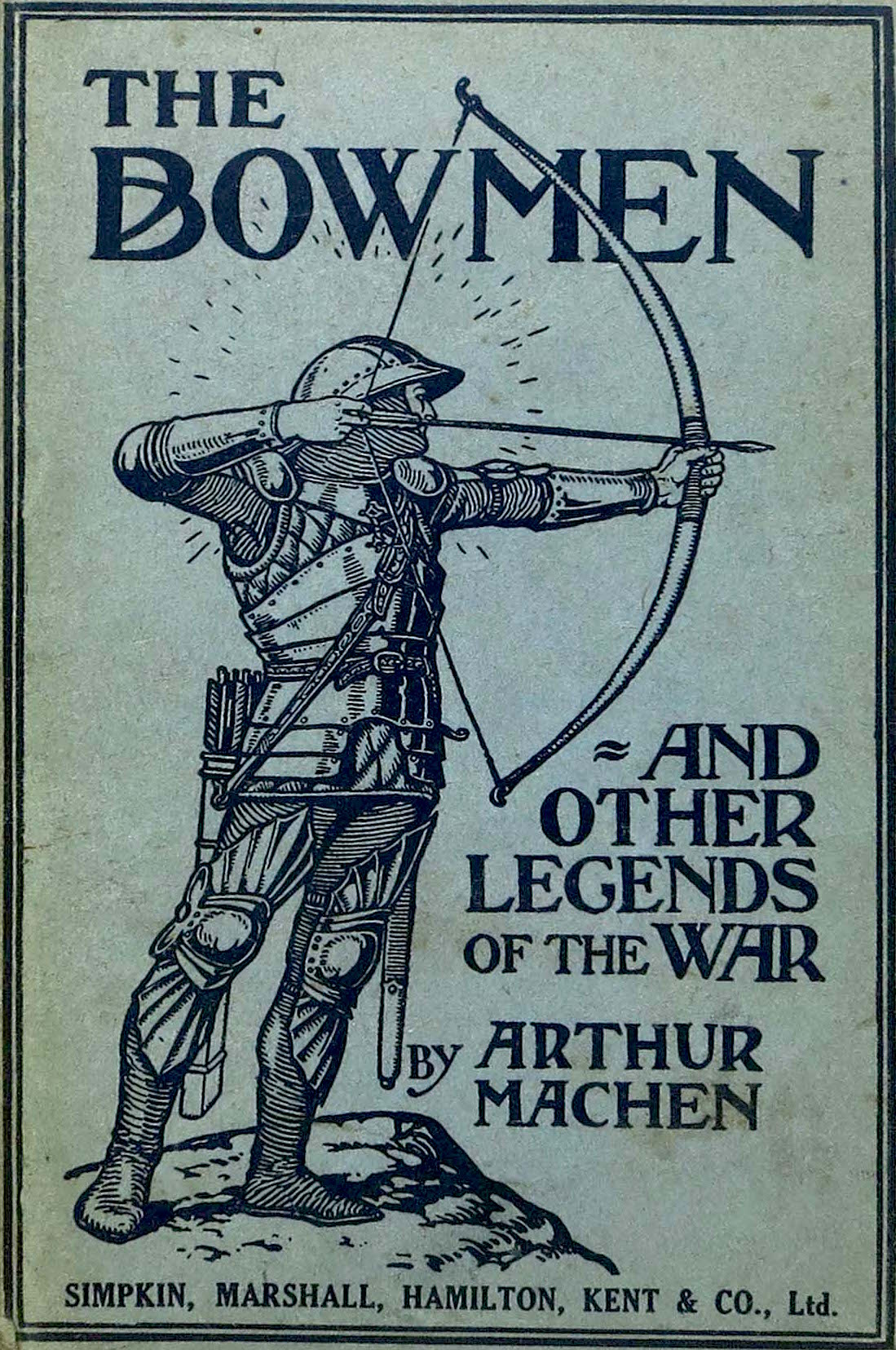

For reasons of space, several works (such as A Fragment of Life, The Terror e The Green Round) inevitably remain outside our brief reconstruction, but nevertheless we want to mention one last extremely significant experience in Machen's life. In 1910 he was hired as a journalist atEvening news and at the outbreak of the Great War he was catapulted to the front, finding himself writing articles on life in the trenches. On 29 September 1914 it comes out The Bowmen, a story centered on the apparition of St. George and the archers of the battle of Azincourt (1415), which lead the British to a war victory against the Germans. Although the narrative itself is nothing exceptional, some of the English people and some magazines take this literary invention of the Welsh writer as true, turning it into a cult phenomenon: thus was born the legend of the so-called Angels of Mons:

« And as the soldier heard these voices, he saw passing beyond the trench a long line of glowing silhouettes.. They appeared as men carved in the light, bending their bows and with a shout, rattling hissing arrows against the German lines. » [19]

It is the commercial pinnacle of Machen's literary career, who continued to write war-related stories, imbued with mythical-religious elements, for the next five years. During the last two decades of his life, against a very limited production, his work received quite widespread international appreciation. Yet, during the Second World War, Machen ends up with his wife in a poorhouse, from which he is brought out through a collection shared by many writers, such as Blackwood and TS Eliot [20]. He will expire nine months after Dorothie's death, December 15, 1947, in a private clinic in Beaconsfield.

In the valuable volume edited by Guarriello, in addition to a quantity of information and considerations capable of greatly enriching the picture outlined in this short review, there are four Machenian tales unpublished in Italy (The little people, The iridescent, The Strange Adventure on Mount Nephin e Torture). Finally, it is proposed La What yellow that crawls, a parody of the Bread by Machen signed by Arthur Compton-Rickett, testifying to the various criticisms (not always benevolent) received by the novel at the time of publication, to which we have referred. Nonetheless, whatever Compton-Rickett thinks, when it comes to Arthur Machen there is very little to laugh about. His multifaceted work, even after a century or more, can be read as a terrifying panic catabasis, built around that core of the uncanny coveted by Freud and modeled around eerie landscapes, enigmatic creatures and deviant minds.

In July 1924, on the Sewanee Review, Ellis Roberts defended the literary work of the Welshman, arguing that his great strength lay in the ability "to write with a deep spiritual conviction" [21]. Appreciated over time by the various Eliot, Borges, Blackwood, Bergier, King and Del Toro, due to his continuous research beyond the "veil of the realMachen could also count on the absolute esteem of HP Lovecraft which, referring to Pan, he paid homage to him with these words in his famous essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927):

“But the charm of the story lies in the way it is told. No one could describe the cumulative suspense and unsurpassable horror that abounds in each paragraph without following to the letter the precise order in which Machen unfolds in the plot gradual allusions and revelations […]. The sensitive reader, having reached the end of the book, shudders in approval and tends to repeat the words of one of the protagonists: “It is too incredible and monstrous; such things cannot happen in this peaceful world. [...] Because, my friend, if this happened our Earth would become a nightmare " » [22]

Note:

[1] sigmund freud, The uncannyin Essays on art, literature and language, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin 1991

[2] Matthew Mancini, Arthur Machen: Beyond the Veil of the Unknown, in Zothique No. 4/2020, Dagon Press, 2020, p. 6

[3] See: Ibid, pp. 12-13

[4] Jorge Luis Borges introduction a The pyramid of fire, cit. in Marco Maculotti, The fairies, the witches and the door to the Other World: folkloric and ethnographic reliefs on the work of Arthur Machen, in Zothique No. 4/2020, p. 185

[5] Arthur Machen, The story of the black seal, cit. in Maculotti, pp. 185-186

[6] See: Mancini, pp. 14-18

[7] Jacques Bergier, Praise of the fantastic, The Palindrome, Palermo 2018, p. 82

[8] Machen's response to the criticisms raised by some newspapers, according to which the Bread it would have been a stupid and incapable re-chewing of Huysmans 'books:' I hadn't read those books so I got them both. At that, I realized that not even my critics had read them ». Arthur Machen, introduction a A fragment of life, Hypnos, digital edition, pos. 187

[9] Mancini, P. 55

[10] Maculotti, p. 182. The theme was explored by the author in his essay in Beyond the real. Lovecraft, Machen, Meyrink, Smith and Tolkien: five sculptors of universes, GOG, Rome 2020

[11] Arthur Machen, The great god Pan, Adiaphora, digital edition, pos. 128

[12] See: Maculotti, Zothique n. 4/2020, pp. 210-211

[13] Mancini, P. 25

[14] Arthur Machen, cit. in George George, Machen's fantastic allusive, in Zothique n. 4/2020, p. 135

[15] Arthur Machen, Things Near and Far, cit. in Leigh Blackmore, Arthur Machen and the Golden Dawn, in Zothique no. 4/2020, p. 149

[16] Arthur Machen, The hill of dreams, cit. in Mancini, p. 93

[17] Arthur Machen, The secret glory, cit. in Mancini, p. 95

[18] Arthur Machen, The white people, Hypnos, digital edition, pos. 1590

[19] Arthur Machen, The archers, Miraviglia, digital edition, pos. 332

[20] See: Mancini, p. 37

[21] Ellis Roberts, Machen and the critics of his time, in Zothique No. 4/2020, p. 127

[22] Howard Phillips Lovecraft The supernatural horror in literature, in Horror theory, Bietti, Milan 2018, p. 410

8 comments on “Arthur Machen and the panic charm of the uncanny"