In its millennial path, medieval Christian philosophy finds itself facing the issues of the creation of the universe through the divine Word, of the Adamic language and of the post-Babelic confusion to which the multiplicity of human languages is attributed. Despite the dogmatic adherence to the biblical canon and to the fundamental Platonic and Aristotelian references, important contributions to this study will come on the one hand from the esoteric doctrine of Judaism, the Kabbalah, on the other from the work of Dante Alighieri.

di Jari Padoan

Cover: Giovanni Di Paolo, Light pink (The Divine Comedy, Paradise, Canto LVII), about 1400; Part 2 of 2

(follows from part 1)

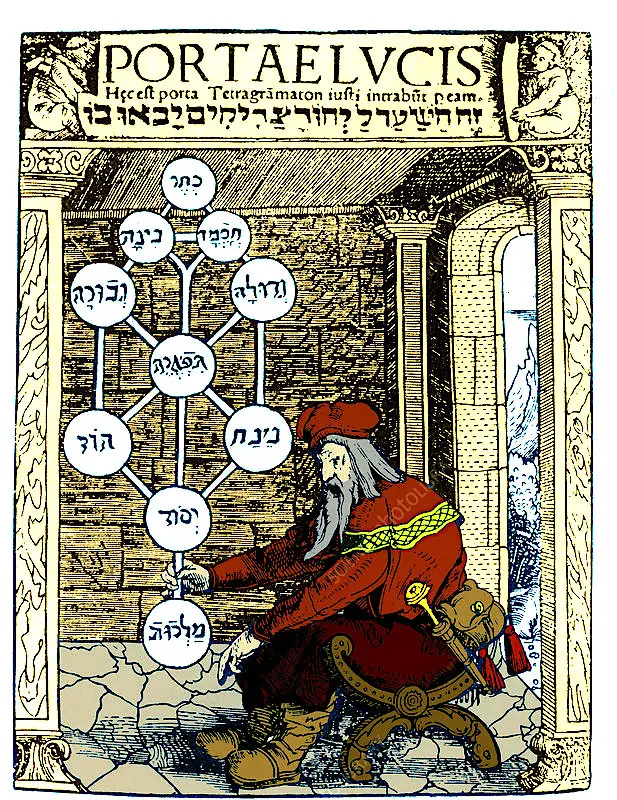

The Kabbalah

However, the Christian West would have dealt with the Hebrew in the humanistic and Renaissance era, and this will happen thanks to what occurs in the European Jewish communities from the Middle Ages onwards. It is precisely in the centers of Judaism of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (especially in the Sephardic community of Arabized Spain and Provence, but also in the Rhineland and Italy) that the doctrine of the Kabbalah (or Kabbalah), the heterodox current of Jewish mysticism founded on specific exegetical and symbolic interpretations of the text of the Torah, and on 'the very idea that the Creation of the world is a linguistic phenomenon. The term itself relates to the idea of something that is transmitted through verbal language, as qabbalah, as René Guénon and Gerschom Scholem among others point out, it means literally "Tradition", "delivery" from someone to someone else, and refers specifically to the wisdom patrimony that would have been transmitted orally by God to Moses on Sinai; or rather it would constitute its esoteric part, while the Tables of the Law represent its official and orthodox one.

Certainly the kabbalistic tradition, as it manifests itself in medieval Judaism, denotes clear denotes influences of Neoplatonic, Hermetic and Gnostic doctrines deeply rooted in the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern area in the first centuries of the Common Era (and neo-Pythagorean influences could also be included in the question, but René Guénon pointed out how in the Kabbalistic and Pythagorean traditions, although both are based on a capital importance attributed to the sacred science of number, the latter is presented and investigated under radically different forms and characteristics).

However, its first manifestations would have already taken place in the second century in the teachings of Rabbi Simeon Bar Yochai, while later, between the third and seventh centuries, there are various redactions of the Sepher Yetsirah, one of the oldest texts of corpus kabbalistic, whose importance is comparable to that of the Zohar, the famous "Book of splendor" also probably written in the first centuries, but widespread in Europe around 1280. The main scholars of the medieval kabbalistic doctrine are mentioned in the figures of Moshe de Leòn, Eleazar Ben Yudah of Worms and Ezra Ben Salomon of Gerona, to whom it is even attributed the codification of the Qabbalah in the strict sense. Like many traditional doctrines, the kabbalistic vision is of abysmal complexity and depth; it can be said that the kabbalist studies the Torah as if it were a symbolic apparatus, which if duly interpreted can restore a scheme, indeed infinite schemes, of the infinite partitions of Being.

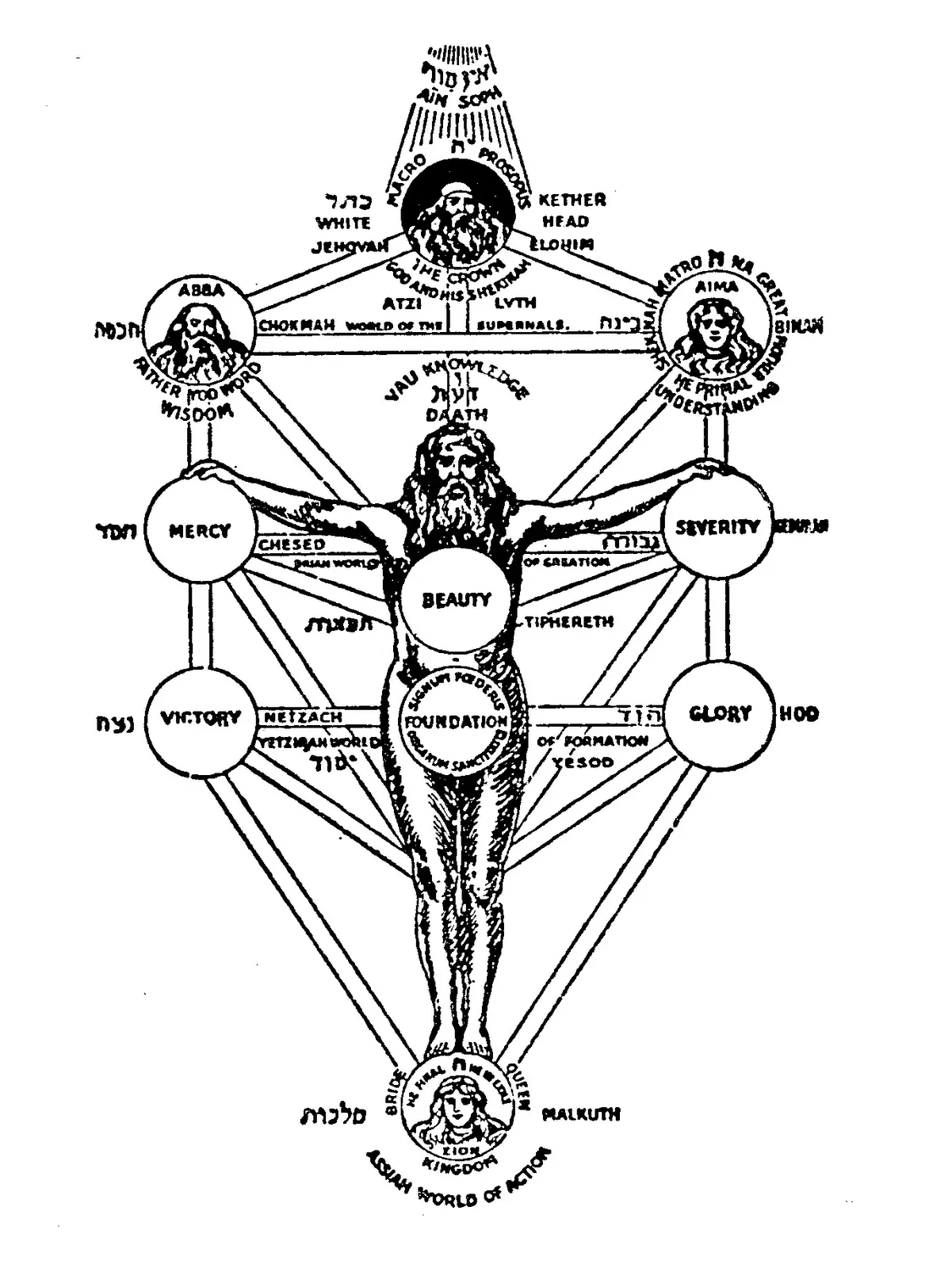

Esoteric exegesis of the sacred text e authoritative aims to identify "Under the veil of strange verses", through the symbolism of the letters of the biblical text, of the references to the so-called ten Sephiroth. These, celebrated as the ten "splendid lights", ten "Emanations" of the Divinity, can therefore be considered either as manifestations of the Divine through the process of emanation of the Being (in a vision so to speak, with an inexact and misleading term, "pantheistic" but strictly hierarchical, similar for example to that of celestial spheres in Neoplatonic and Gnostic doctrines) or as attributes, internal and characteristic aspects of God himself. In both senses, the Sephiroth constitute details Metaphysical "steps" of the cosmos, through which the human soul can make the return to Divinity. This mystical ascent can take place after a vast series of ascetic and mystical-contemplative practices, related to a laborious understanding of the (almost infinite) numerological symbology of the 22 alphabetic letters with which the text of the Torah is composed, which together with the ten Sephiroth therefore constitute the so-called "32 ways" to the Divine.

A simple and indicative example, which interests the kabbalistic numerological reading, can be that of the first letter of the first word of the Hebrew text of the Genesis, that is to say "beresheet": the letter Beth, according to the Hebrew alphabet, is placed at the opening of the story of the Origins because it represents the concept of creation and dualism: dualism since every small part of Creation is in turn a piece of an infinite plurality (the concept of single origin and perfect, from which all that is consequent can derive, but also multiple and imperfect). Only God is the absolute oneness, and that is why the Beth opens the Torah: before Creation, infinite plurality, there can only be the Unique and Absolute, what is represented by the first letter, Aleph.

The Lost Hebrew of Abulafia

In addition to the masters mentioned above, we find among the greatest and most influential medieval scholars of the Kabbalah Abraham Ben Samuel Abulafia, active in the second half of the 1126th century in Barcelona. Abulafia follows a singular line of thought that in some respects is as close to the philosophical principles of Avicenna as to those of Averroè (Cordoba 1198-Marrakech XNUMX). While distancing himself from the idea, common to both great Islamic authors, of the eternity of the world (in total contrast with the idea of a voluntary creation by God, and therefore with the dictates of the Jewish, Christian and Islamic tradition ) we find in Abulafia the concept of Active Intellect, that is the divine one, distinct and superior to any other Passive Intellect, either potential or material. For the Jewish scholar, the key to that Active and divine Intellect can only be the Torah: Abulafia in fact underlines how in the doctrine of the Kabbalah the (Hebrew) language is not intended as a mere signifier that represents a meaning or referent: if God created through the manifestation of linguistic voices and alphabetic signs, such semiotic elements are not mere representations, but them forms on which the elements of the world have been modeled.

Although, historically, the origin of the Hebrew alphabet must be sought in the very ancient Proto-Canaanite alphabet (widespread in the Sinai region around 1500 BC), whose Phoenician branch, during the first millennium before the Common Era, allowed the development both of the Greek alphabet and of the Aramaic, Paleo-Hebrew and classical Hebrew alphabets, for the Kabbalah and for a scholar like Abulafia the divine letters are the building blocks of Being: with them the Torah is written, and the Torah, in a perspective that appears to be the same as the famous hermetic motto "as above, so below", is a scheme of the aforementioned Being. Hence Abulafia, moving away from the typically Aristotelian arbitrary and conventional conception of language (which will lead, in the school environment, to the current of the so-called extreme nominalism by Roscellino et al moderate nominalism of Henry of Auxerre and William of Ockam, as well as taken up by the great Jewish philosopher and physician Mosè Maimonides) states that knowing the combinatorial laws of letters means having access to the key to the formation of each language.

For the kabbalistic tradition, if the aforementioned laws concern the letters of the alphabet, they are naturally magical and divinatory laws: these are the techniques of gematria, which assigns a numerical value to each letter, of the themura, based on the permutation of the letters that form words or phrases, and del notariqon, the technique of sacred acrostics, of which the most famous example comes from primitive Christianity and is the well-known acronym YCHTHIOS (Iesus Christos Theou Uios Soter). But, given anything but negligible, Abulafia also laments the fact that his people, in the course of the exile following the second destruction of the Temple (year 70 of the Common Era), forgot and lost that language; And the kabbalist is the one who studies and works for the discovery of the true primeval Hebrew, that is the matrix of every language.

Particularly fascinating, although it tends to make the question even more complex, is the theory supported by a disciple of Abulafia's "circle". This would argue that the before purchasing, language spoken by Adam would have been as divine as it was human, since it was born from a covenant between the Lord and man; the Progenitor would later devise a language natural used between him, Eva and their children. The Babelic confusion, being much later, involved this "official" and exoteric idiom, albeit ancient; but the original hierolanguage of Adam, in reality, it would have been guarded by only one of his distant descendants, or by Seth, an enigmatic figure of the Noachite lineage.

It is not known whether Abraham Ben Samuel Abulafia succeeded in his personal search, that of reconstructing the divine language with which the Creation took place, with which God spoke with Adam, which was handed down to Seth and which remains perennially silent and hidden among the signs. of the Torah. But it is instead probable that, through the diffusion of his theories among Italian Jews, and in particular with certain intellectuals in contact with theelite active cultural at the University of Bologna, the aforementioned theories would have been taken into consideration by a certain young Florentine poet.

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri, who in all probability stayed in Bologna at the end of the eighties of the thirteenth century, attending schools of rhetoric more than those of law, in a period ranging from 1304 to 1307 is a political exile from Florence, condemned to the stake in absentia. In these years the Poet crossed Northern Italy in continuous wanderings (in Brescia at the court of Corrado da Palazzo, in Treviso at the Da Camino family, then again in Bologna by his friend, also an exile, Cino da Pistoia ...), and it is in this period that he begins the writing of the work that will consecrate him supreme poet.

Just the Divine Comedy, in its immeasurable variety and cultural depth of universal work by definition, in addition to the obvious and well-known references to the illustrious Homeric, Virgilian, Ovidian models and so on, would denote inspirations of Islamic matrix (as underlined by Miguel Asín Palacios and above all René Guénon in the his L'ésotérisme de Dante, 1925). This has been argued in the light of certain similarities, which would bring the otherworldly path imagined by Dante closer to what Muhammad would have undertaken in the so-called Destiny Night in which he had the Divine revelation (mentioned in the suras XVII and LIII of the Koran); moreover, the researches of Guénon and, more recently, of Maria Corti and Sandra Debenedetti Stow have shown how they would emerge, especially in the XNUMX. Paradiso, references to kabbalistic symbology.

In this period in the first decade of the fourteenth century, Dante devoted himself to writing two other works of capital importance: the Of Vulgari Eloquentia and Convivio. If in the case of the Convivio we are facing the first philosophical treatise written in the Florentine vernacular after centuries of Latin and Greek (comparable cases occur only with the works in the Catalan vernacular by Ramondo Llull and with the Treasure of the famous "teacher" of Dante himself, Brunetto Latini), with Of Vulgari Eloquentia we have the first text in which the Christian Middle Ages faces an organic project of search for a perfect language. Text that opens with the obvious observation that the actual plurality of vulgar languages spoken in Italy and Europe is contrasted by the noble and authoritative fixity of Latin, the undisputed model of universal grammar and, from the point of view of time, artificial (since it was believed to have been specially conceived and structured by the Roman scholars). Dante the poet expresses himself in Florentine, his beloved mother tongue; but as a thinker nourished by Latin culture and scholastic theology (as well as a politician who longs for the return of a traditional and supranational Empire, see Monarchy and the fourth treaty of Convivio) naturally writes in the language of philosophy, politics, the Church and international law: this is why the DVE., apologue of the vernacular devoted to the search for an "illustrious" language in the wake of Latin, is written in the aforementioned Latin.

Demonstrating the outstanding notions of comparative linguistics of its author, the DVE exposes how the various languages born and developed from the Babelic confusion would have multiplied ternally, first following a wide diffusion in various areas of the world (known, which at the time substantially coincided with the Old Continent and North Africa) and then concentrated in a approximate area of Western Europe which today could be defined as Romance, distinguishing itself in language ofoc,oil need Yup, between which a certain degree of kinship is clearly noticeable. And it is at this point, analyzing the idea of an evident genetic link more or less distant between various so-called historical-natural languages (a fact already intuited and addressed by the authors of the Genesis), which Dante comes remarkably close to theories of modern historical linguistics and in particular to the concept of differentiation into linguistic groups belonging to the same families, in turn coming from those sets that represent the largest degree of linguistic kinship, the so-called superfamilies.

At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, linguists Alfredo Trombetti and Holger Pedersen hypothesized the existence of one very ancient linguistic superfamily, called "nostratico", from which linguistic families extremely distant from each other such as Indo-European, Afro-Asiatic and Altaic would later derive (and according to some, such as Joseph Greenberg, many languages of the vast Amerindian family also originate from ouratic). According to these theories, our own languages would have been spoken in a large area of the Eurasian continent in an era between 15000 and 12000 BC, towards the end of the last Würm glaciation. The reconstructions of historical linguistics indicate this period of the lower Paleolithic as the "Babelic" moment in which one or more communities of speakers shared morphologically very close languages, differentiated at very deep levels over the course of the various following millennia (and related models of diffusion).

Entering into the Babelic and Adamic issues, and indeed even before facing considerable problems in the philosophy of language, the Of Vulgari Eloquentia emphasizes (Aristotelian) that the ability to speak is a characteristic human ability (DVE., I, II, 2), understood as the ability to express thoughts and concepts from one's mind by pronouncing words. A form of communication Than we different from that of animals, demons and angels, Dante argues; and he too clearly maintains, appealing to the dominant exegetical tradition, that Adam would have spoken in Hebrew. Once created, man could only express himself with the word El, who are "vel per modum interrogationis vel per modum responsionis"(DVE., I, IV, 4), because as after original sin every man is born crying for pain, the Protoplast he could only manifest his joy, and the highest joy is in God, to whom he turned calling him by name.

That name that Dante, who does not appear to know Hebrew, obviously would have taken from the Gospels (we have in fact "Eli Lamma Sabacthani" in Matteo XXVII, 46 and "Eloi lamma sabachthani" in Marco XV, 34) as well as, in all probability, by Etymologiae of Isidore (VII, 1), who writes, based onauthority by Girolamo: «Primum apud haebreos dei nomen El dicitur, secundum nomen Eloi est". But a little further on, in DVE I, VI, 4, the Vate delves into the question: he indicates with the expression «form locutionis»That typology of language that had been created by God together with the first human soul. That form locutionis original is therefore what today would be defined as universal grammar: those underlying and indispensable rules for the formation of every historical-natural language.

Themes like the universal grammar and linguistic universals were familiar with the philosophy of language within the Scholastica, and scholars such as the great English Franciscan dealt with it Roger Bacon and Boethius of Dacia. Boethius of Dacia, who would have represented an important source for the linguistic reflections that Dante exposes in DeVulgari, was a Danish monk author of the treaty De Modis and a prominent figure of the so-called Latin averrosimo (or radical Aristotelianism, branch of the medieval Aristotelian tradition more faithful to the literal study of the works of the Stagirite and therefore hardly reconcilable with Christian doctrine), which together with the famous Sigieri of Brabant, the Averroist by definition, was convicted of heresy by the bishop of Paris in 1277.

Precisely the figure of Sigieri, indeed his "eternal light / which, reading in the alley of the strami / syllogized true envious people"(XNUMX. Paradiso, X, 136-138) ideally connects us to the third canticle of the Comedy. In an authorial choice among the most discussed within the criticism of Dante's thought, Alighieri places the figure of the monk and scholar in the fourth Heaven (and definitely in good company: King Solomon, Sant'Agostino, Sant'Alberto, San Tommaso, San Bonaventura, Isidoro of Seville, Riccardo and Ugo da San Vittore, Pietro Lombardo ...), seat of the Sun and wise spirits, in which divine judgment permits one concordia oppositorum of Christian personalities very distant from each other (for example, the Franciscan revolutionary Joachim of Fiore, Sigieri of Brabant and the names mentioned above).

Il XNUMX. Paradiso is written by Dante a few years after Of Vulgari Eloquentia, of which, in the famous canto XXVI, he takes up some topical motifs. In carrying out this literary and meta-literary operation, the Poet however carries out a retraction of no small importance. During the great journey, Dante arrived ateighth heaven, the seat of the Fixed Stars to which the Triumphant Spirits are assigned. After the severe examination on the three Theological Virtues to which he is subjected by St. Peter, St. James and St. John, here is the conversation with the «soul first», To which Dante addresses four questions that Adam has already foreseen (thanks to the miraculous "Interconnection" between the various minds, human and angelic, which at the higher altitudes of Paradise are permitted by the divine Power). These questions concern the actual essence of God as the Supreme Good, the concordance between reason and authority, Creation as an act of love, and of course the Edenic language, "the language that I used and that I fei», in his words quoted in verse 114.

In addition to reading in this verse a statement that recalls the theories of Abulafia and disciples (the first language of Adam created by God with man himself, and used only in communication between them; the second language as Adam's natural linguistic ideation and shared by subsequent humanity), the soul of the first man testifies that that one and only primordial language

it was completely extinguished / before the inconsummable overdue / was the people of Nembròt attentiveAs Dante makes him sing in verses 124-126. And further on: "Before I went down to the infernal embassy / I the sum good was appealed to earth / whence comes the gladness that binds me; / And El he called himself then, and this is agreed / that the use of mortals is as a branch / In a branch that leaves and other veins. (verses 133-138).

And here is how Dante rectifies his own statement issued in DeVulgari: the mutability of human languages would also have affected the very ancient, primordial language of man, with which Adam addressed his Creator by calling him by his first name, "I". No commentator of the Comedy has ever explained in a convincing way this original idea of Dante, who famously knew about polysemy of the texts (just think of Convivio II, 1 in which we find the exposition of the four senses of the literary text and of the sacred text, that is literal, allegorical, moral, anagogical). The deduction that the letter indicates by definition the idea of absolute uniqueness would be clear, and it would also be linked to the kabbalistic ideas of Abulafia: the scholar emphasized how the atomic elements of the sacred text, that is the letters, would have meaning, value and power of per themselves, to the point that each letter of the divine name it is already in itself a divine name. Such would therefore be the only one iodine, the first semiconsonant that opens the Tetragrammaton; transliterating the iodine like I there would therefore be a possible source of Dante's "about-face" on the analysis of the question, from De Vulgari Elquentia to the Comedy.

In addition to this, in Adam's monologue we therefore find: the primeval language extinct before Babel, in which one can perhaps read a revival of Dante's historical and magical-linguistic theories of Abulafia; verbal language as an attribute and natural disposition of the human being ("Opera natural is that man speaks / but in this way or so nature leaves / then do it to you according to what he likes», 130-132), as already reiterated in Of Vulgari Eloquentia and in Convivio (II, 8); and the reflection on the temporal and spontaneous change of natural languages that develop and change by human initiative. Extremely important is the way in which, in the narration, the author reaches the effective and direct knowledge of the truth about the Adamic language (as well as the first name of God), which is at the center of the song: Dante addresses the question by talking to Adam in the sky of the Fixed Stars, and up there the Poet arrived there during the journey he was called to make thank you. Dante, as a medieval Catholic immersed in Scholastica (and therefore also in Platonism) in this way affirms that man can reach the Truth only by divine inspiration and not through the purely human capacity of rational speculation.

It is therefore truly remarkable and fascinating how Dante, in the poetic fiction (of a work that marks an unsurpassed peak of world literature), arrogates himself the privilege of resolving definitively, in first-person conversation with the only person concerned who can clarify the question namely Adam, one of the greatest mysteries in human history: that of the language that originated all human languages, of the word before each word.

Bibliography:

- The Holy Bible, edited by the Italian Episcopal Conference, CEI, Rome 2001

- Various authors, Garzanti Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Garzanti, Milan 1988 AA.VV. Encyclopedia of Religions, Garzanti, Milan 1989

- Various authors, The deformed idea. esoteric interpretations of Dante, curated by Maria Pia Pozzato, Bompiani, Milan 1989

- Nicola Abbagnano, Giovanni Fornero, Protagonists and texts of philosophy, volume A tomes 1-2, Paravia / Bruno Mondadori, Milan 2000

- St. Augustine, The city of God, curated by Domenico Marafioti, Mondadori, Milan 2015

- Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, edited by Daniele Mattalia, Rizzoli, Milan 1960

- Dante Alighieri, Of Vulgari Eloquentia, edited by Giorgio Inglese, Rizzoli, Milan 1998

- Domenico Casalino, The secret name of Rome. Metaphysics of Roman times, Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome 2003

- Conrad, Maximilian, Dante and the question of the language of Adam (De vulgari eloquentia, 1. 4-7; Paradiso, 26. 124-38), Salerno Publisher, Salerno 2010

- Sandra Debenedetti Stow Dante and Jewish mysticism, Giuntina, Florence 2004

- Umberto Eco, The search for the perfect language in European culture, Laterza, Bari 1993

- Rene Guenon, Dante's esotericism, Adelphi, Milan 2001

- Rene Guenon, Symbols of sacred science, Edizioni Mediterranee, Rome 1975

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologies or origins, edited by Angelo Valastro Canale, Utet, Turin 2006

- Marco Mancini, The rejection of linguistic diversity, in Giuseppe Longobardi, edited by, The languages of the world. The sciences notebooks 108 of June 1999, Le Scienze spa, Milan 1999

- Gabriel Mandel Khan, Hebrew alphabet, Mondadori-Electa, Milan 2012

- Gianni Pilo, Sebastiano Fusco, The kabbalistic symbolism of the Golem, in Gustav Meyrink, The Golem and other tales, Newton & Compton, Rome 1994

- Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah and its symbolism, Turin, Einaudi 1980

A comment on "Considerations on the question of hierolanguage in the Middle Ages (II)"