The discovery of an entire "Gnostic library" in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945, revealed to the world the "cosmic pessimism" of some of the earliest Christian congregations in the Near East, based on the ontological difference between the unknowable God- Father of the Synoptic Gospels and the "God of this world", a figure who has notable correspondences but also sensitive distinctions with the Platonic Demiurge.

di Friend's Shady

I am the wisdom of the Greeks, and the knowledge of the barbarians.

(The Thunder: Perfect Mind)

In the following article I intend to expose some fundamental aspects of that vast movement, philosophical and religious, which takes the name of gnosticism. Referring in particular to the studies of Nicola Denzey Lewis, currently visiting associate professor at Brown University, I wish to present the question starting with the most significant event for research in the sector: the discovery of an entire Gnostic library in Nag Hammadi in 1945 [1]. Before this unexpected finding, the main sources were the polemical writings of Christian authors such as Irenaeus, Ippolito Romano, Epiphanius and others. Nag Hammadi made it possible to verify their reliability and to facilitate the identification of the central elements of the Gnostic phenomenon. Lastly, here I introduced a reflection on the presence of Gnostic elements in modern and contemporary thought and society.

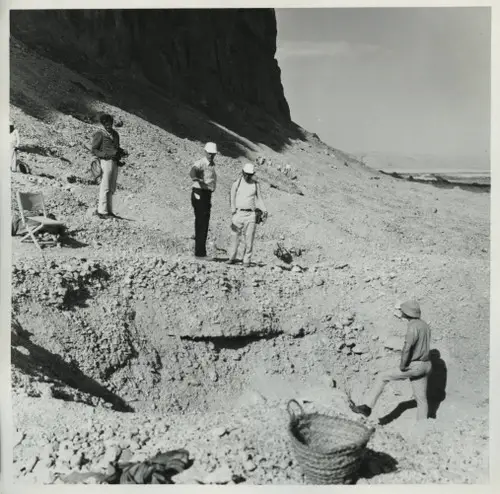

A singular discovery

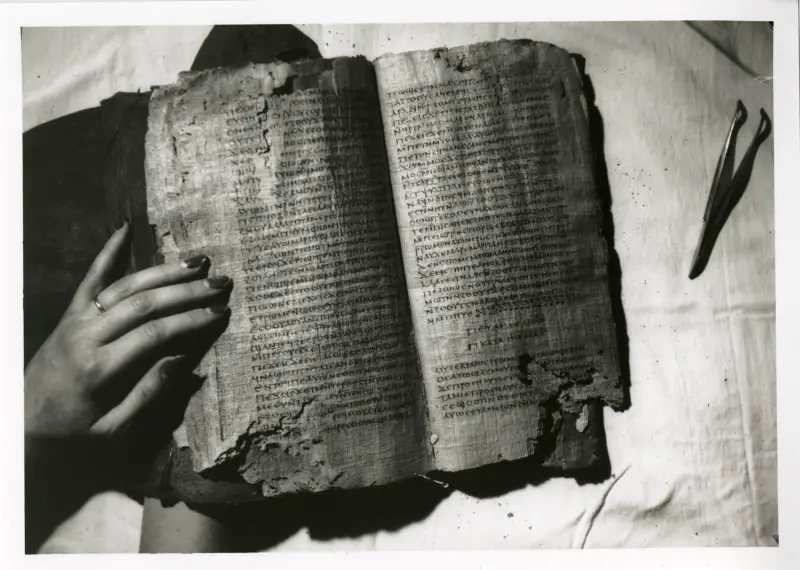

It's a sunny morning in 1945. A man named Muhammad 'Alī al-Sammān is digging around Nag Hammadi, a village in Upper Egypt, looking for a natural fertilizer similar to manure, and accidentally unearths an earthen jar containing fragments of papyrus. Disappointed at not having found a treasure inside, the young man entrusts the codes to his mother, who uses some of the ancient pages to fuel the fire in the fireplace. At this point the story takes on dark tinges: in a fight for revenge, 'Ali kills the murderer of his father and entrusts the codes to a local priest for fear of being stolen by the police. The priest partially understands their value and gives them to the competence of a school teacher, who sends them to Cairo; there they end up in the hands of the antique dealers and they are sold, in 1951, to a professor from Zurich, who bought them on the occasion of Carl Gustav Jung's birthday (it is no coincidence that one of the Nag Hammadi codes is precisely called Jung Code). In 1956 all the codices are found again in Egypt, al Coptic Museum of Cairo, where the extent of their discovery is finally realized. It is a collection of esoteric texts, of Gnostic and Christian matrix, attributable to the first centuries of the imperial age; this discovery is destined - a point on which all interpreters agree - "to change forever the image we have of ancient Christianity" [2].

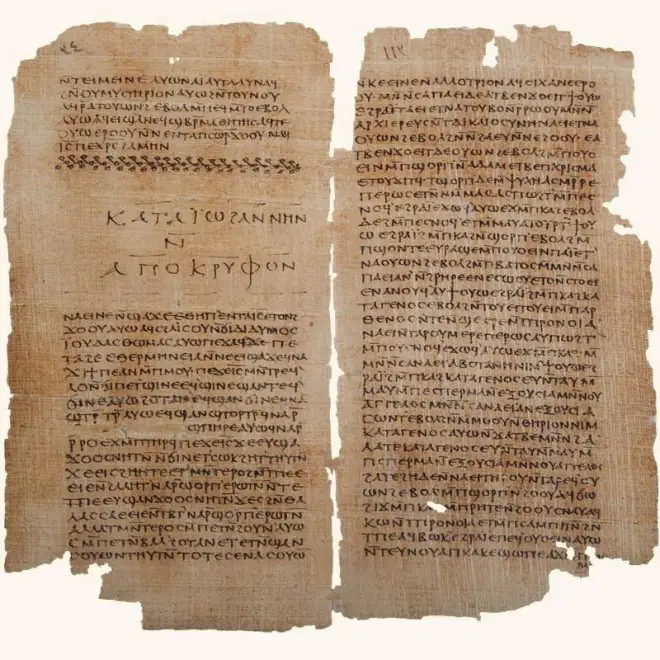

The Nag Hammadi Codes

The Nag Hammadi Codes - as they are now universally known - were originally written in Greek and then transcribed in Coptic, the language widespread in Egyptian monastic circles around the fourth century, where they escaped the destruction caused by the distinction between "official" expressions and "illicit" forms of Christianity. It is possible - it is at least the most accredited theory - that this sort of library gnostic was deliberately hidden when the bishop of Alexandria in Egypt, Athanasius, established with an official act which books were legitimately judged as Scriptures (therefore endowed with salvific value and reliability) and which instead were to be considered prohibited, useless and harmful texts for the faith. It was 367 and it is possible that then, in a climate of generalized danger, a local monk decided to save these writings from destruction and bury them in the desert with the hope that someone would bring them back to light again.

These are above all controversial texts. There is no consensus, for example, on the attribution of the “Gnostic” character to these codes, as if they were “alternative” works with respect to an official and dominant version of Orthodox or Proto-Orthodox Christianity. In the second century, age of their compilation, in fact, there was not yet a canon of official texts shared by the believers of the new confession. Born of Judaism, Christianity had inherited the scriptures of the Jewish community, translated into Greek in the Alexandrian form of Seventy, and from a formal point of view it didn't go further than that. Not yet endowed with a specific theological and doctrinal identity, this nascent state involved numerous projects of philosophical interpretation of the founding experience narrated by the first collections of sayings and facts from the life of Jesus of Nazareth. The various readings were not "stiffened" in the definitive expressions then assumed with the Councils.

In fact, in the Mediterranean basin, there was initially a proliferation of very heterogeneous works, all variously inspired byencounter between the Jewish and the Greek traditions. In the second century only a few texts (such as i Gospels synoptics or Paul's letters) had already established themselves, in an informal and rather spontaneous way, as a shared heritage of the new collective experience of the various realities of the faithful, and were consulted alongside the Greek text of Seventy. Marcion's attempt to abolish the Old Testament writings, in his opinion proponents of a distorted image of God, in favor of a revelation entirely centered on the New Testament, was violently opposed by the primitive Church, which perhaps in this way arrived at a first canon and a rudimentary definition of one's identity [3].

The Nag Hammadi codices should therefore not be considered as a sort of "Gnostic Bible" in antagonism with the synoptic Gospels or, in general, with the New Testament literature, but rather - in line with the various commentaries and exegetical writings of the time - as works of explanation of the biblical text. These writings, in fact, [4]

they did not intend to replace the Gospels, the letters of Paul or the Hebrew Bible. They had to be read alongside the latter, most likely to guide their interpretation. Ultimately, the Gnostics in the second century were likely based on a body of scripture very similar to that of their opponents. What differentiated them was the way they interpreted it.

Gnosticism as cosmic pessimism

But how did the Gnostics interpret the Scriptures? This question leads to a heated debate among scholars about the nature of Gnosticism. In general we tend to distinguish the gnosis, which is a speculative attitude aimed at enhancing a pessimistic interpretation of the cosmos as a place of chance and punishment, from gnosticism, which instead describes a complex of metaphysical systems (often oscillating between the theological and the mythical) developed in the bosom of nascent Christianity, although not all of which can be traced back to Christianity in its proto-Orthodox and then Orthodox form.

As a modern category, the definition of "Gnosticism" has been heavily criticized, since it seems to describe a unitary movement that does not seem to have existed. However, while acknowledging that the first centuries saw a plurality of proposals and interpretative thrusts approaching in an almost equal way in the dense network of relations between Christians and non-Christians, scholars still believe that they can identify a common trait to the diversified set of trends philosophical of the time: theanti-cosmism, that is the persuasion that the cosmos is the deformed product of a lesser God, evil and arbitrary, as opposed to the absolute transcendence of the good God identified with the Good of Plato and the God-Father of Gospels synoptics.

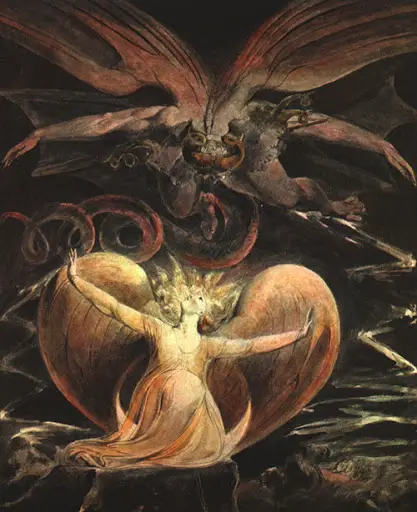

In general, the Gnostic cosmogonies - far from discussing "the harmonious order of heaven, variously obtained in the totality of its parts" (Timaeus, 40a) - they start from this principle: the world is the natural place of evil, hatred, suffering. The constitutive structure of the cosmos reveals this ontologically evil and absurd foundation of the physical being, continuously linked to the chain of needs. Life is bad for the Gnostics; the very universe of men, overwhelmed by dynamics of selfishness and death, can only sink into ever darker darkness, ignorance and blindness that lower existence to a bestial status, of oppression and aggression, of slavery moral and submission to sexuality.

The world cannot be the product of a good God - far from it! It is the aborted creature of an evil God, who revealed himself to history in the figure of Yahweh, the self-referential and violent divinity that the Jews have assumed as the only God and who represents the hypostatization of the will to power, strength and arbitrarities that dominate the cosmos. «I form the light and I create the darkness - says Yahweh - I do good and I cause disaster; I, the Lord, do all this "(Isaia 45,7). How can this be the God to whom the greatest philosophers have referred, and to whom Jesus of Nazareth invited us to entrust ourselves, speaking of him as the principle of love, relationship and life?

Here then is an underlying plot unraveling: these two Gods, the Gnostics say, are not the same transcendent force. The evil of the world is undeniable, the suffering that emerges from the vegetative life and the discomfort that lashes the psychological one cannot be traced back to any positive reality, to any Creator who made the cosmos as a "good thing" (Genesis 1,31). The God of the Old Testament, the angry and exclusive despot, that demonic and tribal reality named Yahweh, he created the world, he made it in his image and likeness, he is responsible for the evil that torments the existence of 'man; not the God-Father, not the philosophical God of Plato, who revealed himself in Greek history and in the story of Jesus of Nazareth as the true God, as the God of all gods, superior to any terrestrial and celestial tyranny.

Now that principle absolutely Other had compassion on men: against the God of the Jews, hypostasis of will and power, the true God has revealed himself to the world, and allows his elect, through knowledge (the gnosis), to "free oneself" from this life of anguish, so as to be able to overcome the ontologically evil limits of matter and return to the true homeland of all theoretical men, the kingdom of God, which is pure intelligible spirit.

The lesser God: the fusion of the Demiurge with Yahweh

Il dualism, therefore, radicalizes the soul-body polarity of Platonic philosophy by proposing a pessimistic vision of reality based on a sort of ontology of need, pain and death, at whose origin there is only one God, Yahweh, author of evil. Now, perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Nag Hammadi texts is that Yahweh comes - for a sort of cross-reading of the text of the Genesis with that of Timaeus - to be identified with the Platonic Demiurge, the artisan god who, inferior to Ideas, shapes the cosmos according to the mathematical coordinates of their proportions. For the Gnostic schools, in fact, [5]

la Genesis it is an important sacred text, but there are also other sacred texts with which it must be harmonized. Among these, the most significant are the letters of Paul and the Timaeus, the Platonic dialogue on the creation of the world.

The Demiurge, in this dynamic of syncretism, thus becomes the author of matter, of that matter which is evil and which is at the root of physiological needs, an inexhaustible source of human pain, and therefore would be responsible for the lacerations that impoverish and mortify the human being. 'existence. In Gnostic anthropology there is no room for a sort of spiritual nature of evil, which is entirely traced back to the action of the flesh, on which both the innate drives and the demons (or Archons, or even gods) who want to limit the human being to the dust, to the earth. To matter.

In reality, however, in man - and it is here that the possibility of salvation emerges - there is also, as in prison, the spirit (pneuma), a spirit that comes from the pleromatic world, the happy homeland of the unknowable God, and which men have forgotten to possess until the coming of the Son, of the Jesus-Logos, which revealed that in everyone there is a "spark" of that superior divine reality. The understanding of having in oneself a "reflection" of that God totally other it leads to the denial of life as a material complex and translates spirituality into one Noluntas - even if, according to the Fathers, often entirely theoretical [6] - which makes evasion from the world, the homeland of the Demiurge-Yahweh, the backbone of every Gnostic experience.

The Gnostic Demiurge yesterday and today

It may seem strange, yet it is not so difficult to find in some unsuspected concepts of modern philosophy and theology some "updated" counterparts of the Gnostic Demiurge. Modern culture no longer knows, perhaps, the complicated mythologies of the past, in which the forces that stir in human dynamics were projected into a transcendence that was neither spatial nor temporal; yet, nevertheless, he never stopped giving voice to schools of thought that made pessimism towards the life of the flesh the main reason for the lack of relationship between the physical world and moral justice.

One might ask, for example, whether it is Gnosticism (or - as it would be better to say - gnosis) that possessed Protestantism that Nietzsche attacks, with the aggressiveness of a reformer, of it The Antichrist and it The twilight of the idols (in the latter work with a famous expression: «Life ends where it begins the "kingdom of God" " [7]). Or, taking a step back, if the thought of Arthur Schopenhauer, which in the world sees the product of a cosmic impulse capable only of translating into the aggressive multiplication of life and the struggles of oppression dictated by need [8]. One might ask, again, if the same philosophy of Gnosticism does not represent a renewed form of Gnosticism Simone Weil, at least where it places the good as "de-creation", that is, as a subtraction from the dynamics of power that structure the complex reality of material life.

Gnosticism somehow survives, and the Gnostic Demiurge with him, although he is now called volunteers, now call it power, now explicitly becomes the diabolical principle of the Christian tradition [9]. Here is what we read, for example, in a widespread writing of the Jehovah's Witnesses [10]:

People of different religions ask spiritual leaders and guides why there is so much suffering. Often these respond that it is the will of God, who long ago established what would happen, including tragic events. […] Do you know why some make the mistake of blaming God for all the suffering in the world? In many cases they take it out on the Almighty because they think he is the ruler of this world. They do not know a simple but important truth that the Bible teaches. As we saw in chapter 3, the true ruler of this world is Satan the Devil.

And in fact in chapter 3 we read: «Jesus never doubted that Satan was the ruler of this world. […] Indeed, Jesus explicitly defined Satan 'the ruler of this world' (John 12:31; 14:30: 16:11). The Bible even calls him 'the god of this world' (2Corinthians 4: 3, 4) " [11]. Once again there is an evil Demiurge, surrounded by fellow Archons, at the origin of evil, so that God can be "exonerated" of the responsibility of suffering.

In a more elaborate and complex way, yet sharing the same dualistic and pessimistic demands, this tension is also found within the contemporary theological literature in the Catholic sphere. Here is what a contemporary theologian writes as Vito Mancuso: "Christianity is the contestation of the original structure of the world" [12]. For Mancuso, in fact, "all bodies, from the largest celestial configurations to the smallest terrestrial microorganism, have sprung from force, from that procedure regulated by force which is called natural selection": it is force, he writes, quoting Pascal, the reine du monde [13].

The oppression and violence that torment the world are nothing more than the spontaneous consequence of the intrinsically blind and instinctual constitution of the being-energy, which, condensing into matter, determines the competition and the dynamics of death that come from nature to society and relational dimension. Hence the consequence: the good is not of this world, it is a gash that transcendence makes in the immanent reality of the flesh and of things. "The good - writes Mancuso - is against the law of nature" [14].

In general, therefore, regardless of the New Age and the recent, as often banal, esotericisms pop which can be traced back to ancient Gnostic wisdom (the manifesto of which was, I presume, Da Vinci's code by the American novelist Dan Brown), it may be interesting to note how well above the Nag Hammadi desert, and rather far from the smoky mystifications of the editorial fashions of the moment, the themes and the conceptual schemes - so little perceived by those who profess them - of the most suggestive cosmic pessimism of the ancient world.

Conclusions

Giustino writes in his first Apology: "We have been taught that in the beginning, God himself being good, created all things from shapeless matter for the benefit of men" [15]. To have taught it to Justin and to his family - we read - are the Prophets, from whom "Plato also derived the affirmation that God created the cosmos by shaping the matter that was without form" [16]. After this broad and inevitably hasty overview, it is perhaps possible to realize that what distinguishes the fideistic nucleus of Christianity in the first centuries, like all Orthodox Christianity afterwards, is the essence intimately platonic to conceive the relationship that divinity has with the world. The conviction, that is, that the universe is the work of a creative principle that turns everything in the good, an element with respect to which the Gnostic mentality, yesterday and today, possesses severe perplexity.

It is a difference with important implications. The hatred that Gnosticism manifests for the world is capable only of being translated into subversion, withdrawal from the social order, resistance to the realization of collectively valid demands. It becomes Noluntas, abstinence from wanting and doing. The framework in which Platonism and Christianity inscribe the creation of the cosmos is, on the contrary, aimed at a practical implication: the continuation of the work of creation in the human world. The earth is man's responsibility (cf. Genesis 1,28) and the same discuss what happened in the beginning turns out to be aimed at an entirely ethical, even political question: "which city should be the best and of which men it can be composed" (Timaeus, 17 C).

Note:

[1] I mostly refer to ND Lewis, The Nag Hammadi manuscripts. A XNUMXth century Gnostic library, Carocci, Rome 2014. Original edition: Introduction to “Gnosticism”. Ancient Voices, Christian WorldsOxford University Press, 2013.

[2] Ivi, p. 33.

[3] «A certain Marcion of Pontus - tells Justin - even now he is teaching those who follow him to believe in a god greater than the Demiurge; [...] causing many to blaspheme, deny that God was the creator of everything and believed that above him another god, greater, had done greater things "(Justin, First Apology, 26,5, in: The apologies, New City, Rome 2001, pp. 51-52). Due to this separation between Yahweh and the New Testament God, there are many Fathers of the Church - Irenaeus in the lead - who will connect Marcionism with Gnosticism.

[4] Almost completely outdated is therefore the position, adopted by Hans Jonas in one of his important studies, according to which Gnosticism is the product of a pre-Christian teaching derived from the East. See H. Jonas, Gnosticism, SEI, Turin 2002. First publication: The Gnostic Religion: The Message of the Alien God and the Beginnings of Christianity, 1958.

[5] Lewis, The Nag Hammadi manuscripts, cit., p. 226.

[6] In apologetic sources, Gnostic rites are sometimes described as excessively austere, sometimes as orgiastic and morally illicit: see, for example, the extract from the first book of Epiphanius da Salamis' Panarion quoted in ibid., P. 61.

[7] F. Nietzsche, The twilight of the idols, Adelphi, Milan 1983, p. 52. First publication: Götzen Dämmerung, 1889.

[8] See, in particular, the second book in A. Schopenhauer The world as will and representation, Einaudi, Turin 2013. First publication: The world as will and imagination, 1819.

[9] In Orthodox Christian theology, of Augustinian origin, evil is nothing but the deprivation of good, the only ontological reality (it is to avoid this ontological dualism the Fathers of the Church have argued that the same matter is not coeternal with God, but comes from nothing). A figure like that of the Gnostic Demiurge is in no way identifiable with the devil of tradition, devoid of any creative capacity and expression of a destructive drift resulting from a disordered exercise of his own creatural freedom.

[10] What Does the Bible Really Teach ?, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, Pennsylvania 2005, p. 108. Original edition: What Does The Bible Really Teach ?, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, NYC 2005.

[11] Again, in another emblematically titled publication, Knowledge That Leads to Eternal Life, it is said: "Since Satan is the ruler of this world and the god of this system of things, he and those who uphold him are responsible for the present condition of human society and for all that afflicts humanity. No one can honestly say that God is the cause of these difficulties "(Knowledge That Leads to Eternal Life, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, Pennsylvania 1995, p. 77. Original edition: Knowledge That Leads to Everlasting Life, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, Pennsylvania 1995).

[12] V. Mancuso, Refoundation of the faith, Mondadori, Milan 2008, p. 169. First edition: For love, Mondadori, Milan 2005.

[13] Ivi, p. 47.

[14] Ibid, p. 178. In reality Mancuso rectifies his position in subsequent works: from being a "consistent disciple of Simone Weil" as defined in the 2008 Preface of this edition, he will come to adopt diametrically opposed positions, in line with the theology and natural philosophy of the Jesuit French Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, according to which "love, far from being de-creation, is the fulfillment of creation, and everything proceeds from matter, even the soul, even the spirit, even love" (ibid., p. 12).

[15] Justin, First Apology, 10,2, in: The Apologies, cit., p. 34.

[16] Ibid, 59,1, p. 86.