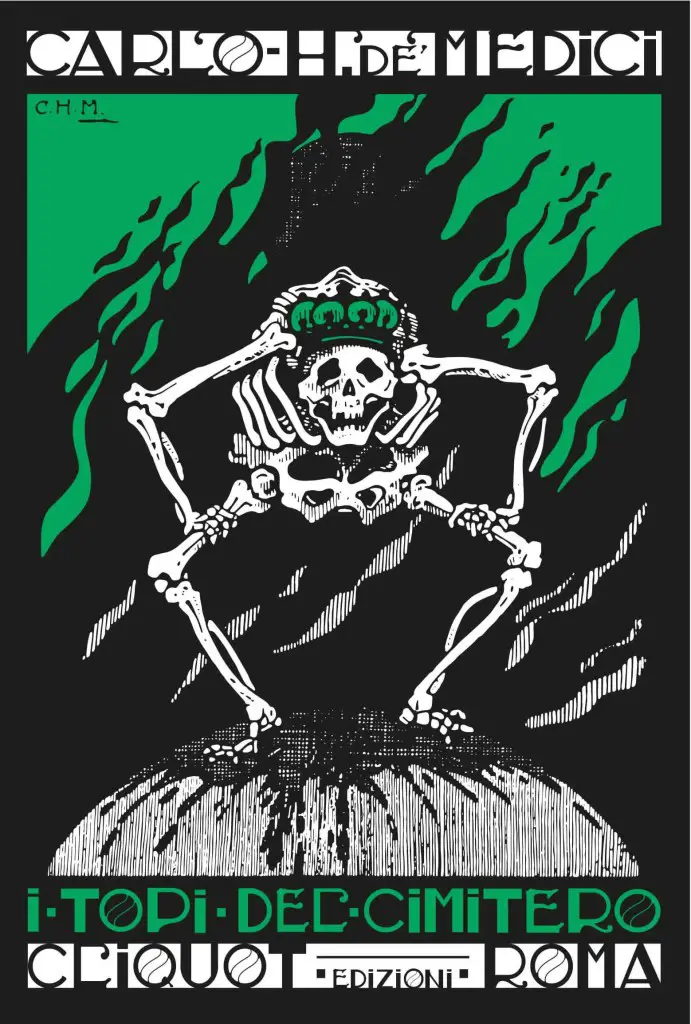

In the panorama of Italian fantastic and supernatural fiction, a prominent place must be reserved for Carlo H. De 'Medici, whose "black" stories, written in the 20s, were inspired by both the psychological horror of Edgar Allan Poe and Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, both from the French decadentist vein. Here we analyze the stories of him contained in the anthology "The cemetery mice", recently reprinted by the types of Cliquot Edizioni.

di Marco Maculotti

ORIGINALLY published on Limina

Cover: Collier Twentyman Smithers, A Race with Mermaids and Tritons, 1895

And, in the immense light that appeared to me, unexpected in so much darkness, I saw the great fever of restlessness: the superb madness of restlessness, hovering over the universe.

Carlo H. De 'Medici, Guland

It is perhaps not nice to say, but there is no doubt that most of the time horror writers, even the greatest, have known only a shred of the honor that fate would have crowned them following their death, most of the time premature. : think of Edgar Allan Poe, arguably the most influential writer of the modern era, who died delusional on the streets of Baltimore, in a state of confusion, perhaps a victim of alcoholic intoxication, and whose genius was fully recognized only in the following decades.

Think of HP Lovecraft,[1] which partly followed in his footsteps, but translating the "simple" Gothic horror into cosmic horror, and which was precisely defined by Jacques Bergier[2] "A cosmic Poe": even the Providence Dreamer was almost completely ignored during his life, no publishing house ever published a collection of short stories for him and, reduced to a state of almost absolute poverty, he died not even fifty years old due to health problems due to to malnutrition. The fate of WH Hodgson,[3] British writer who, at the turn of the century, was able to perfectly blend the old horror story with the novel space science fiction, was still different, but no less sad, having said goodbye to this world just over forty, struck from a grenade on the Belgian front during the First World War.

So far we have only nominated English-speaking, English or American writers, if you prefer; but Italy also had its own cursed writers, unrecognized in life and which deserve to be rediscovered now, having not been possible before. One of them is Carlo H. De 'Medici, who was among other things a journalist, illustrator and scholar of the occult sciences, about which he personally wrote also very difficult to find treatises. The interest in the cabal and esoteric doctrines can be explained in part by the Jewish origins of his father - "a wealthy Parisian Jewish banker", "who by royal decree of 1889 was authorized to call himself De 'Medici, with the right to extend the surname to the children "[4] -, this comparing him to another writer of the occult of the same period, the Austrian Gustav Meyrink,[5] author of the novel The Golem, set in the Jewish ghetto of Prague, so full of kabbalistic and occult suggestions.

And if in 1927 Meyrink wrote The angel of the western window, which some consider the summa of his esoteric vision, the same year he recorded the revised publication of the "cruel tales" by Carlo H. De 'Medici first published three years earlier with the title The cemetery mice, and then re-edit yourself as Cruelty. The types of Cliquot Edizioni now offer us the work again with the original title, but including, in addition to all the stories of the '24 edition, also the previously unpublished ones published in the '27 edition - and the splendid original illustrations by the author. From the double title, however, the most experienced reader will be able to easily guess the greatest literary influences for De 'Medici in the XNUMXs: the aforementioned Poe, his European counterpart Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, and again the French decadents ultimate, namely Huysmans and Baudelaire. Influences that emerge clear from the reading of these stories, which also denote a prose not without a certain originality, and a pregnant taste, as well as for macabre, also for the Ideal e the Sublime.

In Great brig, for example, it is the longing to abandon the unbearable spleen of these "dying cities, prone under the weight of centuries-old nightmares, of ancient regrets, of indelible atavistic remorse",[6] mentally leading the narrator towards distant seas, on the melodiously dreamlike wave of a siren's song, "in the dazzling flickering of the sun, towards the infinity of solitude", finally arriving "at certain ports that no one knows [...] built by magicians, beyond the storms of passion, where the proud minarets rise, in the clear silences, in the motionless splendor of eternal things ».[7] But the price to pay for leaving everything is abandon yourself to the waves of the ocean, "singing the crazy impossible songs" and listening to the song of the sirens it is the very reason: "Yours are my treasures that are in the moon," a supernatural fairy will say to the reckless sailor.

In return you will give me your useless and deceptive mind. Am I not worth that much? Whoever loves me and wants to be loved by me must sacrifice all his thoughts, all his memories: for me, he must lose reason.[8]

The character of the supernatural woman - siren, fairy or muse that is - returns at other times in the work of De 'Medici; for example in The friend of the poet, "As beautiful as the women we love in dreams are [...] an angel's face and a siren's body", an ideal lover who eventually vanishes into nothingness, like the Melusina of medieval folklore, following a kind of flaw on the part of her husband. Here the broken taboo has to do with the poet's purity of soul, who "one day he won the big lottery, and became rich":

From that day on, she never came again, nor did I ever meet her again. I looked for her for days, for months, for whole years. I called her madly, screaming and moaning, in the atrocious darkness of my life, my immense pain, my deadly and endless abandonment.[9]

Or we can still name The Silent, a mute and perversely sinister figure who closely resembles the Tosca of the Tarchetti, well-known Piedmontese scapigliato of the previous century, but also the Olympia ofSandman di ETA Hoffmann[10] ("it looked like a doll: an automaton").[11] But in the disturbing features of the Taciturn one we can also see the female reincarnation of the Great God Pan di Arthur Machen:[12] like the Welsh writer's Helen, De 'Medici presents her as "very beautiful, but in the features of her pale face, something inert, agonizing, emerged, and gave those who looked at her with attention an indefinable sense of unease, almost of terror ».[13]

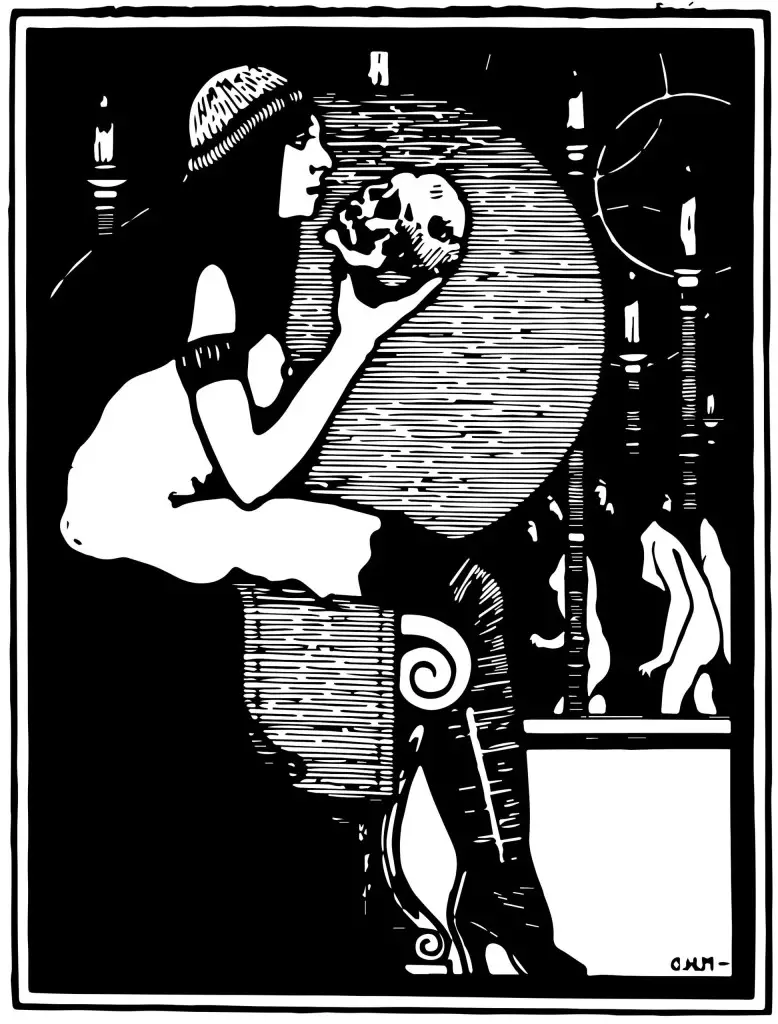

Fairy or siren, muse or witch, the woman in the stories of De 'Medici, as well as in the poems of Baudelaire and in the macabre tales of Poe, is idealized to the nth degree, highlighting how most of the time Eros e Thanatos go hand in handas well as the amorous ecstasy and the most debilitating madness.

The protagonist of Why, not being able to have the body of the beloved in life, he obtains it in death, taking care of the same in its last beats of life and then being able, after death, to keep it forever, for its only venerable gaze. Not dissimilar is the intent of the protagonist of Maddalena, who following the tragic death of his beloved wishes to eternalize her in a wax statue, as much alive as possible:

I wanted to possess a perfect effigy of lines and colors: I wanted to keep the semblance of my Magdalene, rosy, warm, colored with youth, prosperity and life [14]

[...] my wax Magdalene, enlivened by the blood that I had transfused into her essence.[15]

The highest peaks of the collection, however, must be identified in our opinion in two other stories, Guland e After. In the first, an alter-ego of De 'Medici returns as the protagonist decadent, prostrated by the spleen of the gray reality - "my dark disease, yet very sweet!"- and perpetually in search of the flame that makes it burn with ever greater brilliance: «I want everything to be restless, like my soul. I want everything to shake, moved by the storm that revolves in my head!».[16] Here the protagonist almost rises to faustian hero, of hybris Luciferian, who shoots darts in the direction of the sun to challenge its divine authority:

with a diabolical and rapacious gesture - I know the dark mysteries of universal life - I have torn from the world its center: the invisible and absolute center around which the whole secret system of spheres revolves and moves and balances itself. I tore it up and forced it into my skull. […] I then moved the great constellations of the sky to my liking; I directed at my whim the immense migratory stars of limitless spaces; I changed the fates of the old cancerous and mad planets in the methodical, haunting their revolutions. [...] I have all bewildered. I have shaken everything. I have all messed up [...] with my brain mad with superhuman pride.[17]

The appearance of four supernatural ladies - Morgana, "the white fairy of innocence"; Melosina, "the pink fairy of love"; Urgele, "the blue fairy of repentance"; and Viviana, "the golden fairy of forgiveness" - would seem to bring the madman in front of the mirror of his madness for a moment, but he does not give up on the latter: in the moment in which, "stunned by their words", he is about to yield , sees "in the immense confusion of the sky, among the thousands and thousands of fleeing stars" appear "Guland, the black star, the star invisible to mortals, the star of Satan" - the US star.

Tear yourself off [...] your useless pupils! - shouts to the four ladies - to see beyond the Earth! So you will be able to see my heart, up there, tight in the heart of Guland: my heart that vibrates, that quivers, that beats, that sparkles in the world: my restless heart that dominates the universe ....[18]

After, for its part, is distinguished from all the other stories in the collection by its similarity to a platonic dialogue between the two characters, rich in esoteric suggestions that betray hermetic studies,[19] wisely combined with the most modern discoveries of twentieth-century physics:

In the universe, you know, everything is similar. From the macrocosm to the microcosm, as the ancient and forgotten magical wisdom attests us: from the colossal spheres of unexplored regions to the imperceptible atoms, which are nothing more, as the most recent scientific theory states, than tiny planetary systems.[20]

The eventuality of a life after death, with these premises, is analyzed according to the doctrines that already belonged to Plato and the Pythagoreans: at the moment of his birth in this world, man is nothing but a simple embryo, from which "a new chrysalis can be born, more perfect, more developed, more suited to the mission for which he is destined"[21] - from his daimon, Plato would have said. And the real birth, that of the "golden butterflyFrom the chrysalis, is realized only at the end of what we very naively call life, that is to say at the time of death on this plane of existence.

We are the innumerable, infinite little seeds, in which the essence-life, latent everywhere in the universe, involves to develop. We are the passive matter, in which this essence-life sprouts, to evolve and transform itself into spirit-life: the vile matter, in short, through which the atoms destined to form are procreated. the eternal molecule in the absolute.[22]

Thus, in the final analysis, although in the "atrocious hour of supreme anguish" matter is annihilated, the snares that imprison the self crash and a frightening vertigo hovers over everything, finally we will discover that "the astral cord is broken. Man died to human life. He was born to the divine life».[23]

Note:

[1] On the Lovecraftian cosmic horror and the pregnant influence of dream activity on his work, see M. Maculotti, “Oniricon”: HP Lovecraft, the Dream and the Elsewhere, in AXISmundi, February 2018

[2] J. Bergier, Praise of the Fantastic, Il Palindromo, Palermo 2018; in this regard see M. Maculotti, Jacques Bergier and "Magic Realism": a new paradigm for the atomic age, in AXISmundi, June 2019

[3] On Hodgson, see M. Maculotti, William Hope Hodgson's Journey at the End of the Night, on AXISmundi, April 2020

[4] F. Cenci, "Carlo Hakim De 'Medici: history of a rediscovery", preface to CH De' Medici, The cemetery mice, Cliquot, Rome 2019, p. 9

[5] In this regard, see M. Maculotti, Gustav Meyrink at the frontiers of the occult, in AXISmundi, September 2018

[6] De 'Medici, op. cit., p. 23

[7] Ibid, p. 24

[8] Ibid (our italics)

[9] Ibid, p. 35

[10] For an analysis of Der sandmann, see M. Maculotti, Eyes, puppets and doppelgänger: the "uncanny" in ETA Hoffmann's "Der Sandmann", in AXISmundi, November 2018

[11] De 'Medici, op. cit., p. 29 (emphasis added)

[12] On the Helen del Bread of Machen, see M. Maculotti, Arthur Machen and the awakening of the Great God Pan, in AXISmundi, October 2018

[13] De 'Medici, op. cit., p. 29

[14] Ibid, p. 97

[15] Ibid, p. 98 (emphasis added)

[16] Ibid, p. 66 (emphasis added)

[17] Ibid, pp. 66-67 (our italics)

[18] Ibid, p. 72 (emphasis added)

[19] Above all comes to mind the Corpus Hermeticum, a treatise that tradition has it written by the mythical Hermes Trismegistus, whose oldest drafting dates back to the imperial era (II-III century AD); translated into Latin by Marsilio Ficino, it became the greatest source of inspiration for Hermetic and Neoplatonic Renaissance thought; but also the Kybalion, written by anonymous "Three Initiates" and published in 1908, which presents itself as one of the first summa.

[20] De 'Medici, op. cit., p. 103

[21] Ibid, p. 106

[22] Ibid, p. 112 (emphasis added)

[23] Ibid, p. 108 (emphasis added)