In the decline of a world ruled by men only, an intrepid nun with a warrior spirit does not hesitate to lash the consciences of popes and emperors. Mystic and prophetess, theologian and philosopher, leader and preacher, composer and doctor, that of Hildegard of Bingen is one of the most original voices of the twelfth century. Let's retrace the adventurous events together.

di Claudia Stanghellini

Given the high infant mortality rate, that of Hildebert of Bermersheim, ministerialis of the bishop of Speyer, and Mechtilde of Merxheim is a rather large family even for the time. Ildegarda, born in Bermersheim - German region between the Rhine and the Nahe - in thesummer of 1098, is the last of ten brothers, but unlike all the others, as reported by his biographer Theodoric of Echternach [1], from an early age she manifested the prophetic gift of visio and is plagued by serious ailments, identified today as "classic migraine”, Which will accompany her for the rest of her life [2]. Perhaps driven by his particular condition, the parents soon decide to offer it to religious life (oblation), a rather widespread custom for the society of the time. So at the age of about eight, Hildegard was removed from her family of origin to be entrusted to the material and spiritual care of a young noblewoman, Jutta of Sponheim, who had consecrated herself to God and carried out her novitiate at home [3] under the spiritual guidance of a devoted noble widow, Uda. In the years spent in Sponheim, it is Jutta who takes care of Hildegard's training, who devotes himself to the study of Latin and the Psalms, and learns to play the psalter.

from Juttae life [4] we learn that on the death of his mother Sophia, which took place between 1110 and 1111, Jutta cultivates the desire to leave for a pilgrimage. Her brother Meinhard, however, deeply opposed to her, manages to distract her from her intentions with the help of the bishop of Bamberg, who persuades her to join a monastic foundation to lead a life according to anchorite ideals such as included. Jutta approves the solution and on 1 November 1112, together with Hildegard now fifteen, he enters the Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg, followed shortly after by the solemn profession of both. The fame of sanctity of Jutta, locked up for love of Gods in a tiny cell and tested by ascetic practices that today would be considered extreme [5]soon spread throughout the region, inspiring other young women to follow him. As the female monastery of Disibodenberg begins to grow, Hildegard enters fruitfully into the monastic life, although her illness often makes her so weak that she cannot even walk. But we mustn't be fooled by her appearances: there will be no physical frailty that can come between this woman and her goals. On the contrary, for a creative mind like yours it will even become an unexpected resource to strengthen his spiritual and political authority in a world where culture and power are the sole responsibility of men.

On 22 December 1136, Jutta flies to the sky already in the odor of sanctity and Hildegard takes her place as abbess [6] of the nuns of Disibodenberg. The choice of the sisters is unanimous. She not only she is she the disciple of Master's degree, but it has all the essential characteristics to lead the community: political concreteness and diplomacy, a decisive and resolute character and, last but not least, the attitude of a fighter. But Jutta's death is also the occasion for a meeting that will be of capital importance in Hildegard's life. At his suggestion, Abbot Kuno decides to have Jutta's life written down and instructs for the drafting Volmar, monk "sober, chaste, wise in soul and speech" [7], who working side by side with the abbess in the realization of the work, will win her most sincere esteem and trust, so much so as to become the first magister and subsequently secretary. Volmar will be destined to become one of Hildegard's closest and closest friends and to share fully the prophetic mission that will soon be assigned to her.

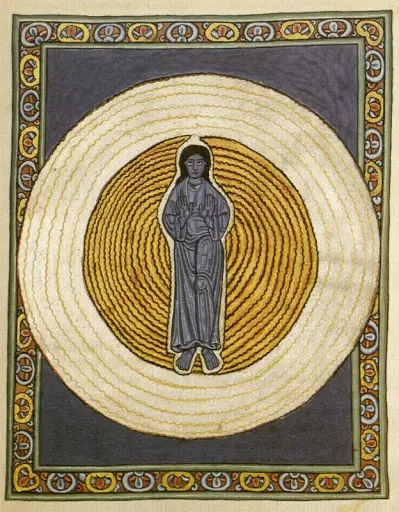

Seeing things others don't see can be dangerous in a time when the Church fears an ever more widespread and uncontrolled spread of heresies, and the boundary between mysticism and possession is rather blurred. For this reason Hildegard, who until she was fifteen used to speak naturally and spontaneously about her visions, entered Disibodenberg suddenly became much more reserved and shy about it. Apart from Jutta, only Volmar and the abbot are aware of it. However, as she herself reveals in the Praefatio the Scivias, in the forty-third year of his life he hears a voice from heaven: "O fragile human being (homo), [...] say and write the things you see and hear ". But being Hildegard "shy to talk about it, simple to explain it and uncultivated (induced [8]) to write about them "he will have to do it exactly the way he will see and hear them. In a world where women do not have access to an education equal to that of men, it is Wisdom itself that instructs it [9]:

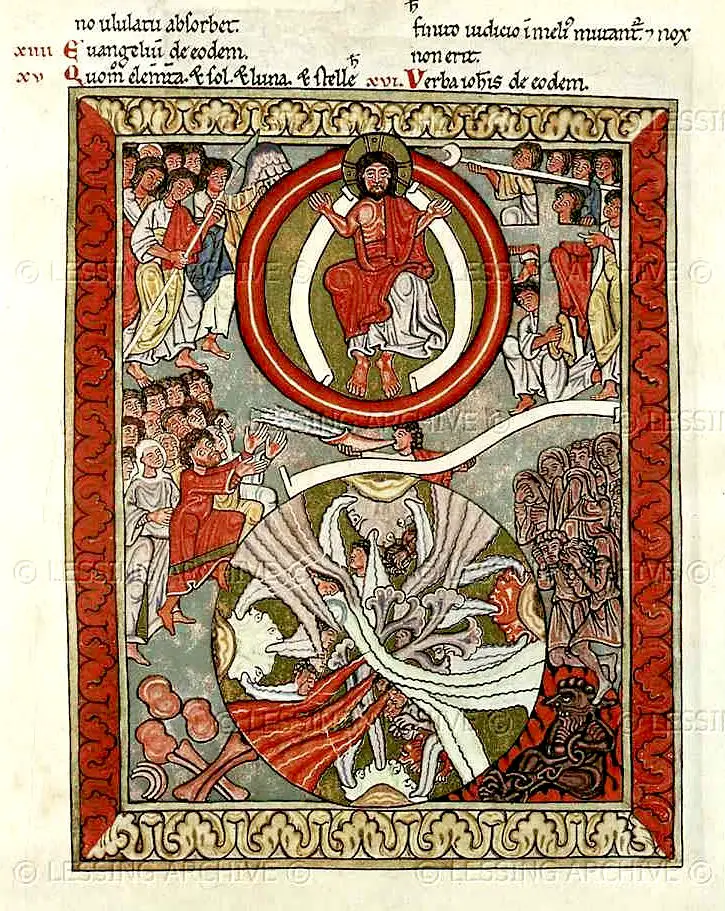

In the year 1141 of the incarnation of the Son of God, Jesus Christ, when I was forty-two years and seven months: the fiery light of a very strong lightning, coming from the sky that had opened, totally penetrated my brain and inflamed my whole heart and the chest, like a flame that does not burn, but warms, as the sun warms what its rays rest on. And suddenly I had become wise and understood how to comment on the books, that is, the psalter, the gospel and the other Catholic volumes of both the old and the new testament, even if I was not able to explain the words literally or the articulation in syllables nor did I know the cases or times.

Despite the power of the call, "for the dubious uncertainty, fearing the malevolent judgments and gossip of the people", Hildegard at first refuses to write, until she falls to bed sick "lashed by God". At that point she confides in Volmar, who makes himself available to help her with the formal revision of the text. Through him, a first fruit of their work is made known to the abbot Kuno, who after an initial reluctance, having ascertained the orthodoxy of the contents, gives permission to Hildegard and Volmar to collaborate permanently in the drafting of the visions, which they will later also be presented to Heinrich, archbishop of Meinz. This first group of writings constitutes the principle of Scivias, a work that inaugurates the prophetic trilogy of Ildegarda and was completed only in 1151, after a work lasting ten years.

Due to her incredible gift, Hildegard sees herself called to hire the role of prophetess, despite the fears and anxieties that arise from it. A gift of which he becomes progressively aware over time, to the point of delineating a real one phenomenology both in the most autobiographical features of his texts, and in response to those wishing to further investigate the nature of this extraordinary phenomenon. Of particular importance in this regard is Hildegard's correspondence with Guibert of Gembloux, destined to become, among other things, his last secretary after Volmar's death.

In 'epistle 103r, Hildegard, prompted by Guibert's questions, describes her extra-sensorial perceptions in great detail. First of all, she points out, everything that she sees and hears is seen and heard not through the five external senses, but with the spirit, while his eyes remain wide open and she is perfectly awake. In fact, there is not the slightest suspension of the normal faculties: her visions have nothing to do with the dream, with the trance or theecstasy, on the other hand, phenomena commonly attested, so much so that contemporaries already recognize theexceptional rarity of the Hildegardian mode of vision, completely concomitant with physiological sight. Hildegard then underlines how his gift is inexorably related to suffering from the disease, which gives her no respite from childhood. She strongly perceives, through her words, the contrast between the passivity of her fragile body, often and willingly confined to bed, and the lightness of her spirit that thanks to the gift of visio it can rise up to heavenly altitudes: "But I stretch out my hands to God, so that He can lift me up like a feather, which, devoid of all heaviness and strength, flies through the wind" [10].

Then he goes even further and says he sees a light, baptized by her "Shadow of the Living Light" (umbra vives luminis), which extends without borders over everything and is brighter than the rays of the sun filtering through the clouds. On this light the Scriptures, sermons, virtues and works of men. In visio everything is immediately intuited: «E at the same time I see and hear and understand, and almost in an instant what I understand I learn " [11]. The words that Hildegard sees and hears, in his visions, do not resemble those of human language, but are like burning flames and clouds moving through the clear air. The form of this light, continues Hildegard, cannot be grasped any more than one can hold his gaze fixed on the sun and yet it is always present to his spirithence his permanent ability to interpret reality with a prophetic gaze. Sometimes it happens, finally, to see another light in the "shadow of the Living Light", the "Living Light" (lux vivens), but its ineffability is such that it is almost impossible for the company to describe it [12]:

And in that same light I sometimes, infrequently, see another light, which I call "Living Light", which I am doubtless less able to explain how I see it, than the first [the shadow of the Living Light]. And as I stare intently at you, all sadness and pain are removed from my memory, so then that I no longer have the manners of an old woman, but of a naive girl.

In summary, Hildegard sees, with the inner eye, images that present themselves as Figures e signs. These are then immediately understood thanks to a spiritual voice which explains the figural or allegorical meaning of the images. In his visionary works this process, by its nature uniform and indivisible, is abstracted into its two essential components, namely the imaginative one, object of allegorical interpretation, and the interpretative one, allegoresis itself.

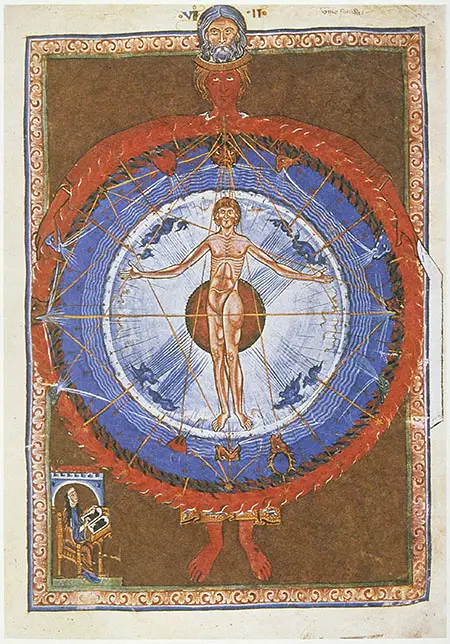

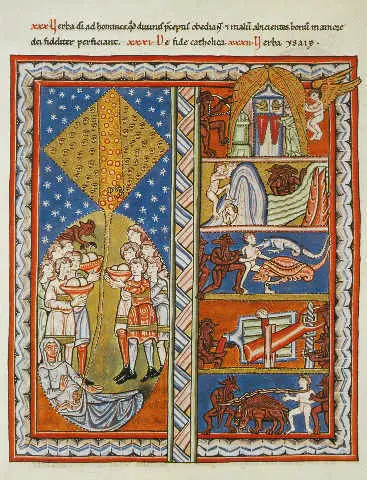

The decade that goes from 1137 to 1147 sees the progressive acceptance of Hildegard by the powerful surrounding male world, first in the restricted context of Disibodenberg and later within the archbishopric of Mainz. However, a more solemn investiture is needed so that his prophetic caliber is in effect recognized and protected from any kind of questioning. And this a particularly delicate historical moment, which still does not see full reconciliation between Church and Empire and in which heresies, such as the Cathar one, continue to spread. It is therefore necessary great caution to present to the ecclesiastical world any kind of novelty on the theological level. From this point of view it Scivias, although in terms of content it is a compendium of Christian doctrine comparable to other writings of his time, it shows an absolute originality for the prophetic form in which it is conceived and drawn up. In addition to this, as Pereira points out [13], there is also the question of the enhancement ofhuman psychosomatic unit which, despite being in contrast with the dualist heretical tendencies supported in the West by the Cathars, could have been frowned upon, especially in the monastic environment, in the face of the Augustinian definition of man as a "rational soul that makes use of an earthly and mortal body" [14]. And then give it Scivias Hildegard's belief, of an ethical-political nature, that the general decay afflicting the companies, increasingly corrupt and perverted in its customs, is linked to moral weakness that pervades the Church itself, often and willingly willing to allow himself to be polluted by the logic of power typical of the secular world, while "the vital food of the divine Scriptures has already warmed" [15].

It is for this reason that Hildegard, between 1146 and 1147, decided to preliminarily seek the approval of Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the greatest theological authorities of the time, as well as a staunch defender of orthodoxy, who had already taken an active part in attempts to condemn thinkers such as Abelard, William of Conches and Gilbert of Poiters. What emerges from Hildegard's letter is a fine strategic and political intelligence that, relying on the rhetoric of humility and not without a certain captatio benevolentiae, does not hesitate to ask for authorization to proceed along the path taken. Bernardo's response, sometimes militaristic, leaves no doubt [16]:

After all, are you anointed by the Lord, Wisdom is within you and instructs you on everything that we could teach or advise you on?

The die is cast. Only one last obstacle remains: Pope Eugene III. Informed by the archbishop of Meinz, Heinrich, he sends two legates to Disibodenberg to collect a copy of Hildegard's writings. We are in 1148 and the pontiff is presiding the synod of Trier when he is given the most recent, and still incomplete, version of the Scivias. Eugenio reads the work in front of the entire assembly, which as a whole is pronounced favorably. Bernardo di Chiaravalle is among the members in favor. Hildegard finally has the formal authorization she needs to continue her work of writing the visions together with Volmar.

The pope's intervention at the synod of Trier therefore ratifies Hildegard's prophetic authority, which should be protected from any disputes. However, practice often does not adapt to theory, especially if there are strong economic and political interests at stake.

So when, not long after, having the need to make room for a constantly growing community, Hildegard receives the order to found a new convent on the Ruperstberg hill - about thirty kilometers away from Disibodenberg -, not only does he not meet the support of his brothers, but even a strenuous opposition. Abbot Kuno certainly cannot tolerate the removal of the monastery's main source of prestige and wealth, all the more so now that Hildegard's reputation for holiness, "Sibyl of the Rhine", has spread throughout the region, attracting a large number of pilgrims, loaded with offerings. Furthermore, the young nuns under his authority are all of aristocratic extraction and with their rich gifts have greatly contributed to the welfare of Disibodenberg. But Hildegard is unwilling to yield and falls into a state of terrible disease, so powerful as to force her to bed paralyzed.

Kuno and the other confreres, astonished by the singularity of this phenomenon, must give up in the face of the fact that it is a divine warning and are forced to put an end to all types of opposition. Thanks to their surrender, Hildegard can recover her strength, but the road that awaits her to complete the task entrusted to her is still long and tortuous. Thanks to the intervention of the powerful Marquise Richardis von Stade, she manages to obtain the permission of the Archbishop of Mainz - under which the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Ruperstberg falls - to proceed with the foundation. However, when, together with his twenty nuns, he goes to the place to start preparing the future settlement, he has to face the abandonment which that place had encountered. The prospects are so bleak that even her sisters begin to murmur against her, but Hildegard does not allow herself to be disheartened and after some time many wealthy families begin to give donations and choose Ruberstberg as a burial place for their deceased loved ones.

Finally, in 1150, the actual settlement can take place. But the battle is just beginning and the financial and administrative independence of his monastery still to be conquered. If Hildegard can in fact count on the support of the archbishop of Mainz, Heinrich, and his successor Arnold, who, by mutual agreement with the abbots, first Kuno and then, on his death, Helengerus, decree the independence of the foundation and his possessions from Disibodenberg, the same is not true for the community of origin, so much so that the abbess is forced to return to settle the matter once and for all. The cause of the tension is partly of an economic nature and concerns all those properties brought as a dowry by the sisters at the time of their entry to Disibodenberg. Hildegard demonstrates understanding and diplomacy: they could have kept them, together with the assignment of a substantial sum of money, so as to stifle any kind of future economic claim in the bud, provided that the absolute separation of the recent possessions acquired by Ruperstberg is ensured. There is, however, one point of the agreement on which Hildegard cannot compromise: the designation of Volmar as the spiritual guide of the newly formed foundation. Being one of the most erudite and capable confreres, the community is opposed, arousing the indignation of Hildegard who, thanks to his prophetic investiture, launches a very heavy arrow on Disibodenberg, where the monks do not consent to the departure of Volmar [17]:

However, if you ever try to snatch away the pastor of spiritual medicine, then I tell you that you would be similar to the Belial children because you do not observe the righteousness of God; and for this reason the righteousness of God will destroy you.

Such a warning could not have gone unheard, and the confreres are forced to yield. After so many obstacles, Hildegard can finally witness the gradual blossoming of the new community of Benedictine nuns she founded. About fifteen years later, in 1165, thanks to the extraordinary fame, the high protections obtained and the support of the Archbishop of Mainz, she will also be able to open a convent in Eibingen, near Rüdesheim, on the ruins of an Augustinian foundation destroyed by the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, intended for the reception of nuns of lower social extraction. The two sister communities, located on the opposite banks of the Nahe river, will always maintain a close relationship.

A victory, however, does not always follow another. Hildegard, at the time of his solemn profession, knowingly renounced any kind of earthly affection, reiterates this on several occasions both in the autobiographical notes that dot his writings, and in the Carmina. But there are two people in his life that he could never break away from: Volmar - and you saw his reaction to the idea that he couldn't move to Ruperstberg - and Richardis von Stade, sister and disciple whom she considers like a daughter. If the surname sounds familiar, it is because her mother is the mighty Marquise who with her influence and her economic power has contributed massively to support the new foundation and who now wishes Richardis a better position. Not even a year has passed since Richardis took office in Ruperstberg decides to accept the appointment as abbess of the monastery of Bassum.

By now we know Hildegard enough to imagine what her reaction might have been. From the initial upheaval, quickly takes action. At first he appeals to the Marquise von Stade, well aware that it is she, moved by logic of a far from spiritual nature, who is the mind of her at the origin of these machinations. Having failed to persuade her, she flatly refuses to let Richardis go, to the point that the archbishop of Meinz must intervene. Hildegard, then, in a prophetic guise, opposes the human authority of his superior with the divine one, and goes so far as to accuse the archbishop, not too covertly, of being a simoniac; his orders, therefore, would have been disregarded [18]:

O shepherds, complain and weep in this time, because you do not know what you are doing when you disperse the duties constituted in God in the riches, in the money and in the senselessness of corrupt men, who have no fear of God. And therefore your deceptive words, threatening and cursed are not to be heard.

Although there are sufficient elements to consider the election irregular, it must also be said that all the political aims of the von Stade family and the favor of the ecclesiastical hierarchies would not have been enough if Richardis had decided to oppose a firm refusal in the face of career opportunities that they were presented to her, but this was not the case. What were the reasons that led her to accept the position, whether the harsh conditions of the first year of life in Ruperstberg, the pressures of the family of origin or her personal ambition, we will never know for sure. What we know is that Hildegard, despite the bewilderment and deep pain of a betrayed mother, continues not to give up and after the girl's transfer he also writes to Hartwig, Richardis's brother, who as archbishop of the diocese of Bassum would have had the power to invalidate the election, but his heartfelt pleas fall on deaf ears. All that remains is the pope and Hildegard, not wanting to leave any stone unturned, tries. His letter has been lost, but not Eugene's answer, who solomonically evades his petition: the matter, he declares, has already been delegated to the Archbishop of Mainz - the same Heinrich whom Hildegard had accused of simony - who allegedly made sure that the Rule was strictly observed in the Bassum monastery and that, if not, Richardis would be sent back to Ruperstberg without delay. There is nothing left to do but resign yourself to events.

The medievalist and Ildegardian interpreter Peter Dronke notes how on certain occasions it is possible to perceive by Hildegard a certain abuse of his prophetic role, which would not have escaped even Pope Eugene, who, in the central body of the aforementioned letter, warns her from the sin of pride and presumption. Dronke glosses: "She is never less certain that she knows God's will: doing God's will and doing one's will are considered identical things" [19]. If, however, we trust Hildegard's own testimony, according to which: «My soul, however, is at no time deprived of that light, called the shadow of the living light, which I see as if I saw through a luminous cloud the firmament without stars; And in this same light I see the things of which I often speak and to those who question me I give answers according to the splendor of the living light» [20], all accusations of megalomania against him are dropped. Beyond any possible speculation on intentions, it is evident that the one against Richardis is a maternal attachment so strong that it pushes her to struggle with all the tools available to her to prevent her beloved spiritual daughter from falling into error. And yet, like every mother, in the end Hildegard too can do nothing but surrender to the inevitable, that is, the fact that Richardis should be free to make his own decisions, even if they are wrong. It is with this awareness that the mystic, in 1152, wrote to Abbess Richardis in search of reconciliation [21]:

Daughter, listen to me, your mother in spirit, as I tell you: My pain increases. Pain kills the great confidence, the great comfort that I found in a human being [...] Now I say again: Alas, mother, alas, daughter! Why have you forsaken me like an orphan? I loved the nobility of your behavior, your wisdom and chastity, your soul, your whole life, so much so that many said: what are you doing? Now, may all those who feel pain like mine cry with me, all those who, for the love of God, have never felt in their hearts and souls a deep love for a human being like me for you, for a person torn from them in an instant, as you were torn from me. But may the angel of God precede you, the son of God protect you, his mother defend you. Remember your poor mother Hildegard, may your happiness not fail.

Richardis died on October 29, 1152, about a year after his departure from Ruperstberg. It is Hartwig who gives the news to Hildegard in a touching letter, which reveals, between the lines, the bitter awareness a posteriori of having made a mistake - an error that Hartwig attributes to himself, even before his sister - in the having removed Richardis from Ruperstberg. At a time when every event makes its mark, it is easy to imagine that the premature death of the Abbess of Bassum does not leave indifferent those who have worked to counter Hildegard's severe warnings. According to Hartwig's words, it also appears that Richardis had regretted her decision and that, if death had not prevented her, she would have returned to Ruperstberg as soon as clearance was granted. The archbishop of Bremen concludes the letter with a warm thanks, proof that he finally understood that Hildegard's apparent obstinacy was nothing more than the clear demonstration of total dedication to her beloved daughter in her spirit. . Hildegard's response to Hartwig will definitively sanction the reconciliation between the two regarding the troubled affair. Richardis' death, on the other hand, is read in the light of faith in Providence, which has snatched her from the clutches of the world, enemy amateurs, to deliver her to the loving arms of Christ.

In the following years, thanks to the rent correspondence exchanges Hildegard's apostolic work progressively begins to turn also to the world outside the cloister. In his interventions the constant concern towards imperial politics and secular power is evident - remember the schismatic crisis, which took place between 1159 and 1177, which sees the opposition between Popes and antipopes, elected by the emperor -, but above all of the Church, traversed by different and contrasting impulses, such as the pauperism of certain spiritual movements, the spread of heretical concepts such as the Cathar one, prophecy and the formulation of theocratic doctrines. Among his most illustrious correspondents, in addition to Bernard of Clairvaux, there are four popes, the two emperors Conrad III e Frederick Barbarossa, Henry II of England and also Eleonora of Aquitaine. But the progressive maturation of Hildegard's public and prophetic figure is not limited to the written paper.

Starting from 1158 - when the abbess was already the ripe old age of sixty - starts preaching in different areas of Germany. It is incredible if we consider that at the time not all journeys could be traveled by river, but some necessarily by land, and the range of his movements is quite wide: between 1158 and 1161, he went to various communities of the regione along the First name; a second preaching campaign takes place in 1160 between Rhineland , Lotharingia; a third in the region of Reindeer between 1161 and 1163 and finally a fourth in Swabia, between 1170 and 1171. It should be noted that Hildegard addresses sermons not only to the monks in their abbeys, but also to the bishops and clergy during their synods and to the laity in the cities, where the public preaching, in ordinary practice, it is forbidden to women, as it is the prerogative of priests. The exception, in her particular case, is made possible by the formal attestation of her prophetic gift, which places her in a completely extraordinary position with respect to the canonical provisions. Contacts with communities and, within them, with individuals, are often the occasion for subsequent exchanges of letters, thanks to which the established ties have the opportunity to consolidate. Hildegard thus becomes for many a real point of reference: as a prophet, as Master's degree and for the resolution of theological controversies. This is because the undoubted divine election is added to a profound capacity for understanding, matured from the experience of leadership of her community, which allows her to advise in the best way those who turn to her for help or spiritual guidance. She is also well known for hers deep knowledge of herbs and traditional remedies, required, moreover, by the role of abbess itself: the Benedictine monasteries in fact are not concerned only with the care of their own monks, but also respond to the medical needs of the surrounding populations. Ildegarda then, to the knowledge gained in the field, combines an activity of reflection that for the time we can say "scientific". The result is summarized in Liber subtilitatum diversirum naturarum creaturerum, A 'medical-naturalistic encyclopedia which in the manuscript tradition is divided into two separate treatises: the physics, which analytically reviews the vegetable, animal and mineral world, and the Causae et curae, in which he deals with topics of cosmology and cosmography to arrive at the causes of some diseases and to present their respective therapies.

It often happens, therefore, that she is asked about her skills as a healer (old). One of the cases that most marked the imagination of contemporaries, given the recurring presence in the sources, is that of Sigewize, a young woman from the Lower Rhine who is possessed by a demon. After seven years of wandering, this woman arrives at the monastery of Brauweiler, where she hopes to be freed through the intercession of St. Nicholas. However, the demon who bonded with her, questioned about her, declares that he would not go away unless he was forced to do so by a certain old of the Rhine, said, derisively, Scrumpilgardis. Thus, in 1169, the abbot wrote to Hildegard explaining her situation and attaching her request that she be the one to practiceexorcism. The Rhenish abbess tells us that at first she is forced to refuse due to her poor health, but that later changes her mind and agrees to heal the girl by writing for her a complex mise-en-scène that would have had the power. to cast out the demon. His instructions are followed faithfully, but the effects of the exorcism are only temporary and the abbot, at this point, intercedes with Hildegard to personally receive Sigewize in his monastery. Although the abbess and the nuns are terrified of the prospect, they accept and after weeks of common prayers and shared ascetic practices result in the gradual - and finally final - convalescence of Sigewize.

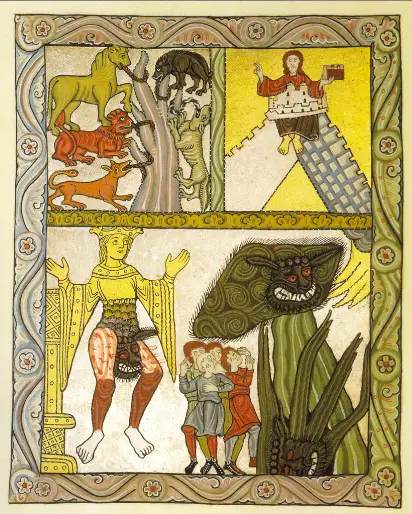

In these same years, in addition to dealing with the ordinary administration of his foundation, cultivating relations of a political and spiritual nature with the outside world and undertaking those numerous preaching journeys which we have had the opportunity to mention, Hildegard also intensified his written production. In the time span from 1151 to 1158 in addition to Liber subtilitatum composes l'Ordo virtutum, the first sacred representation of the Middle Ages, a "musical drama" in which the victory of the soul over the devil with the help of the virtues is staged with allegorical figures. But the corpus music of Hildegard does not end here and also includes seventy-seven songs, gathered according to the indication of the author in the Symphonia harmonie caelestium revelationum, where the human being, through his soul, experiences in himself the sacred symphony of creatures and revealed realities. Also in this period dates back to Unknown language, a real artificial language composed of 1013 words, drawn in an invented alphabet, reported in the text Unknown letter.

From 1158 onwards, his energies are instead dedicated to the completion of the prophetic trilogy, inaugurated almost twenty years earlier by the Scivias, with the drafting of the two fundamental texts of Liber vitae meritorum and Liber divinorum operum, the culmination of her theological production, which gathers in a complex but unitary plan all the knowledge and experience of the Rhenish Abbess, who has now matured, with the arrival of advanced age, an extreme degree of prophetic awareness. In 1173, before the operasia ended, Volmar passed away, who faithfully shared with her the burden of the prophetic mission for thirty-seven long years. Despite the pain of an unbridgeable loss, Hildegard must finish her last effort and to do so she can count on the help of Ludwig, abbot of Sant'Eucario di Trier, and of his nephew Wezelin, provost of St. Andrew in Cologne. Later from Disibodenberg they send a monk, Gottfried, who becomes its new secretary. The latter, among other things, retrieves the biographical material that had been collected in previous years by Volmar, including some passages dictated by the abbess herself, and draws up a libellus, which coincides with the seven chapters of the first part of the Life Hildegardis. Gottfried, however, died in 1176, too early to complete his work. Destined to become heir to this post, after the premature death of the other two designated successors, he is a monk of the abbey of Villers, Guibert of Gembloux, who between 1175 and 1177 establishes a close correspondence with Hildegard who will soon lead him to Ruperstberg, where he will become her last secretary and will share with her what little time she will have left to live. Here over the years will collect and assemble as much biographical material as possible, with the idea of completing the drafting of the Life, a purpose that he will never be able to realize. To conclude the work will be the aforementioned Theodoric, magister scholarum in Echternach, who will undertake the work on commission of the abbots Ludwig of Echternach and Gottfried of Sant'Eucario, friends of Hildegard, despite never having met the Rhenish abbess in person.

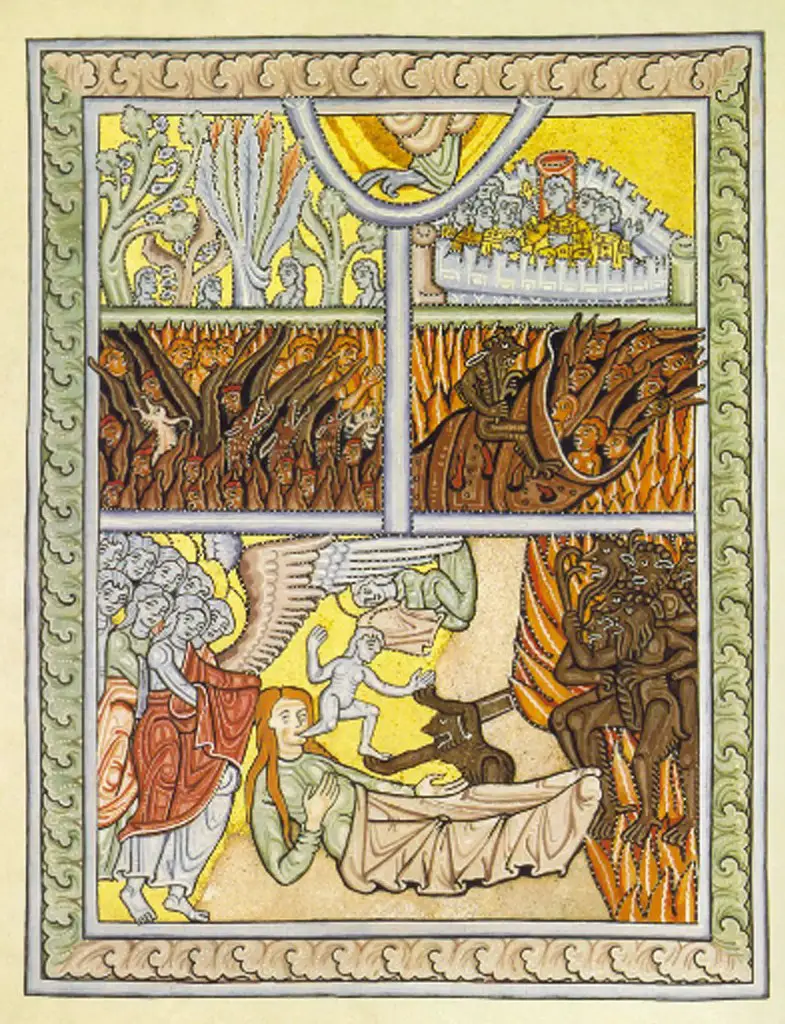

In 1178, the now eighty-year-old Hildegard, a year before dying, had to face one last bitter fight, which could result in the tragic destruction of his community. The abbess, we read in Life [22], has in fact consented to the burial in consecrated land of a "A certain rich philosopher" who from a disbeliever had finally changed his mind and had become one of the most fervent supporters of the Benedictine community led by Hildegard. However the prelates of Mainz, not believing in his conversion and knowing that he was excommunicated, in the name of their archbishop they ordered Hildegard to immediately dig up the man's body and throw it into deconsecrated land. In case of refusal, the penalty would be excommunication of the entire community of nuns, with the consequent impediment to participate in the Eucharist and to sing the Divine Office. But Hildegard with an act that we could define today as civil disobedience, decides to challenge the interdict: with his own baculus - the stick emblem of her authority as abbess - traces the sign of the cross on the grave and it eliminates any clues that could lead to its identification, so that it cannot be profaned.

In this story, the echoes of the clash between Antigone and Creon, between the feet and the law. Once again, as had already happened with the founding of Ruperstberg and the appointment of Richardis as abbess of Bassum, Hildegard does not show herself willing to respect human authority, where she is in manifest contrast with the will of God and her own conscience. . At the same time, however, giving proof of humility and obedience, she accepts to assume all the responsibilities that her act of rebellion entails and thus, even with great pain, refrains herself and her sisters from participating in the Eucharist and singing the praises. divine.

In a vision, however, as she herself recounts, she learns that this is not good for her community and that she should have appealed to the authority of her superiors, the prelates of Mainz, to withdraw their interdict as unjustified. Hence the long and intense letter addressed to them, famous for the particular philosophical and theological conception of music exhibited in it. That of singing, for Hildegard, is a sacred and powerful art, capable of restoring the original harmony of the heavenly homeland, lost after the Fall. For this reason the devil hates him and tries in every way to destroy the teaching and the beauty of divine praises, sometimes even acting in the heart of the Church. Hildegard therefore warns the prelates, with a strong and decisive tone and words that leave little room for interpretation, to pay close attention and caution when it comes to making decisions that shut the mouth of the choirs that sing praises to God. [23]:

For this reason those who hold the keys of heaven [priests], be very careful not to open what must remain closed and close what must remain open, since those who rule over these things will be judged harshly if, as the Apostle, do not do it with concern.

Hildegard's warning is a blade that falls relentlessly on the neck of the prelates of Mainz. This letter, together with the intervention of the archbishop of Cologne who collected the testimonies of those who had witnessed the repentance of the excommunicated, are worthy of bringing down the interdict.

Hildegard died a few months later, on September 17, 1179. At the twilight of that Sunday evening, the sisters testify to witness the appearance in the sky of two very bright rainbows, which spread out to cover the whole earth, one from north to south, the other from east to west. From the highest point, where the two arches join, a clear light erupts, from which a shining cross peeps out, which gradually enlarges and is surrounded by countless circles of different colors, on which many small luminous crosses stand out, one for each circle and all smaller than the first. Spreading throughout the firmament, they flow in greater numbers towards the East and descend towards the ground, illuminating the entire Ruperstberg pass.

Note:

[1] See Theodoricus Epternacenses, Vita S. Hildegardis Virginis in M. Klaes (edited by), Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, CCCM, 126, Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 1993, pp. 1-71.

[2] It is a disease that manifests itself with an "aura" phase in which visual hallucinations can also occur and which according to the neurologist Oliver Sacks can be considered together as a structure whose forms are implicit in the repertoire of the nervous system, and a strategy that could be used for any emotional or, indeed, biological purpose (see O. Sacks, Visions of Hildegard in The man who mistook his wife for a hat, Adelphi, Milan 1986, pp. 222-226).

[3] It was long believed that Hildegard's oblation coincided with his entry into the Disibodenberg monastery. However, this thesis was questioned in the light of a systematic re-examination of the biographical sources. See: A. Silvas, Jutta & Hildegard: The Biographical Sources, Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 1998.

[4] Cf. Vita domnae Juttae included, tr. ing. edited by A. Silvas in A. Silvas, Jutta & Hildegard: The Biographical Sources, cit., pp. 65-88. From here on out Juttae life.

[5] In addition to intense and prolonged fasts, to which was added the permanent abstinence from meat, Jutta wore a sackcloth day and night and upon her death it was discovered that she also wore a heavy iron chain that had carved three deep grooves in her flesh . Jutta reserved these practices for herself and did not extend them to her pupils, to whom she limited herself to giving her example. See Juttae life, IV-VI; VIII cit., Pp. 70; 72-74; 80.

[6] What was originally the Jutta prison, with her death officially became a female monastic foundation, which however continued to technically depend on the abbot of Disibodenberg. Hildegard therefore, from the formal point of view, in the years of Disibodenberg was never abbess in the strict sense, although she had in effect her prerogatives. In many documents, the title attributed to it is that of Master's degree.

[7] Guibert of Gembloux, Guiberti Gemblacensis Epistolae, edited by A. Derolez, CCCM, 66A, Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 1998-1989, vol. 2, ep. 38, p. 377. My translation.

[8] Hildegard's education is a historiographical problem that remains the subject of lively discussion to this day. In fact, from biographical sources it is known for sure that he received a rudimentary education from his Master's degree Jutta, which included learning Latin and the Psalms. Several interpreters, however, including Dronke, believe that his culture and grammar skills, while not formally acquired in school, have come constantly enriching throughout his life, as well as the sources of him that would include, in addition to the Scriptures, also the texts of the Fathers of the Church and Latin classics such as the De natura deorum of Cicero, the Pharsalia of Lucano, the Natural questions of Cicero and the Metamorphosis by Ovid (see P. Dronke, Hildegardian problem, "Mitellateinisches Jahrbuch", 16, (1981), pp. 107-114). The insistence with which Hildegard would persist in defining himself induced it would therefore be due to the need to keep a low and humble profile, which is essential to dispel any doubts about the authenticity of his visions.

[9] Hildegard of Bingen, Sanctae Hildegardis Scivias sive visionum ac revelationum libri tres, Praefatio in Latin patrology, vol. 197, coll. 1065-1082A. From here on out Scivias. Translation by M. Pereira in Hildegard of Bingen. Teacher of wisdom in her time and today, Gabrielli Editori, Verona 2017, p 36.

[10] Hildegard of Bingen, Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, edited by L. van Acker - M. Klaes, CCCM, 91-91B, Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 1999-2001, vol. 2, ep. 103r, p. 260; pp. 258-265. From here on out Epistolarium. My translation.

[11] Ibi, ep. 103r, p. 262. My translation.

[12] Ibi, p. 262. My translation.

[13] See M. Pereira, Hildegard of Bingen. Teacher of wisdom in her time and today, cit., pp. 62 ff.

[14] Augustine, De moribus ecclesiae, Postal Code. XXVII, col. 1132 in Latin patrology, vol. 32, coll. 1309-1378. My translation.

[15] Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias, cit., III, 11, coll. 0714C-0714D. My translation.

[16] Hildegard of Bingen, Epistolarium, cit., vol. 1, ep. 1r, p. 6 s. My translation.

[17] Hildegard of Bingen, Sanctae Hildegardis Explanatio symboli Sancti Athanasii ad congregationem sororum suarum, coll. 1065C-1066B in Latin patrology, vol. 197, coll. 1065-1082A. My translation.

[18] Hildegard of Bingen, Epistolarium, vol. 1, ep. 18r, p. 54. My translation.

[19] P. Dronke, Women and culture in the Middle Ages. Medieval writers from the XNUMXnd to the XNUMXth century, edited by P. Cesaretti, Il Saggiatore, Milan 1986, p. 208.

[20] Hildegard of Bingen, Epistolarium, cit., vol. 2, ep. 103r, p. 262.

[21] Ibidem. Translated by P. Dronke in Women and culture in the Middle Ages. Medieval writers from the XNUMXnd to the XNUMXth century, cit., p. 208f.

[22] Theodoric of Echternach, Life Hildegardis, II, 12, cit., P. 37.

[23] Cf. Ibi, P. 65.