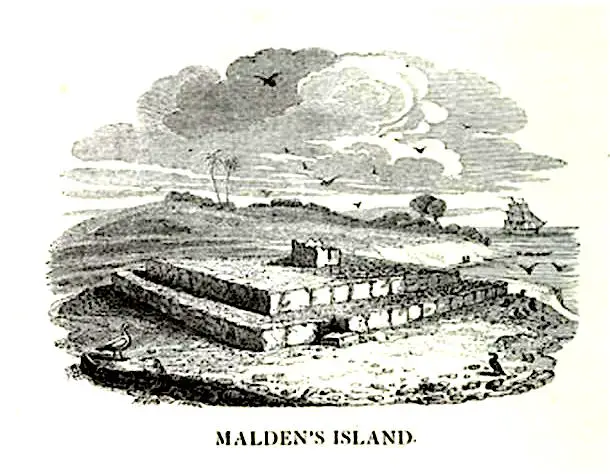

The remote islands of the Pacific are often characterized by megalithic idols and elevated structures (the characteristic "Marae"), once used during sacred rites. Malden Island is no exception, also presenting, among the various sites of archaeological interest, huge streets paved in basaltic stone that nowadays disappear among the ocean waves: an apparently inexplicable discovery that has suggested to researchers the hypothesis of existence, in the past remote, of a lost continent.

di Marco Maculotti

Translation of the article Ruins of Malden Island and The Mysterious Roads that Lead into the Sea by Michelle Freson, originally published on Ancient-Origins.net

Malden is a tiny island in the central Pacific Ocean, which altogether covers an area of approximately 15 square miles (equivalent to 24 square kilometers, ndt). It is one of the Line Islands belonging to the Republic of Kiribati and, although there is no resident staff in Malden, there are occasional visits from foreign boaters. The island is best known for its ruins of unknown origin, its deposits of guano (a valuable natural agricultural fertilizer, made from the droppings of seabirds) and its historical use as the site of the first British nuclear tests.

The triangular shaped island is located at 1.530 nautical miles (approximately 2.800 km, ndt) south of Honolulu and over 4.000 nautical miles (7.400 km, ndt) in the west of South America. Today it is a protected reserve for the reproduction of about a dozen species of birds, as well as a winter stop for migratory seabirds. A small lagoon, entirely enclosed by a strip of land, occupies the eastern part of the island. The latter is connected to the sea by culverts and the water is salty. Most of the island's surface is located south and west of the lagoon. The island is low, no more than 33 feet (just over 10 meters, ndt) above sea level, and devoid of fresh water.

Malden Island is named after the lieutenant Charles Robert Malden, the navigator of the HMS Blonde, who briefly explored it, along with a naturalist and a botanist, during one exploratory mission organized by Royal Horticultural Society in 1825. Malden Island was occupied from 1860 by an Australian company for the purpose of harvesting guano, but all activities ceased in the early 30s. No further use was made until 1956, when the United Kingdom chose the island as the detonation site for its first series of H-bomb tests. At the time of discovery Malden was not inhabited, although the remains of ruined temples and different megalithic monuments indicated that it had once been inhabited.

In 1924 the Malden ruins were surveyed by Kenneth Emory, an anthropologist of the Bishop Museum of Honolulu, who theorized that they were built by a small number of Polynesian settlers who had resided there for several generations a few centuries earlier. There are also, however, those who dispute his theory, arguing that Emory was not motivated to reach different conclusions, and imply that this conclusion was supported mainly to support his thesis that saw in Tonga and Samoa the starting point from which the Polynesian culture spread westward across the Pacific to Tahiti, the Marquesas Islands and Hawaii.

Critics of Emory's hypothesis also argue that Malden may have traces of a human presence far older than that of the Polynesians, which would run counter to Emory's entire paradigm of earliest settlements in the Pacific. However, even today, thirty years later, Emory is considered the leading expert on Polynesian culture.

Field, stone idols and paved streets

Among the 21 archaeological sites discovered have been found platforms of temples, as well as lodgings and tombs. Various wells once used by these ancient settlers were later declared waterless or brackish. Emory theorized that a population of between one hundred and two hundred natives could have produced all of Malden's structures. Field (megalithic platforms on which sacred ceremonies took place, ndt) of a similar type have also been unearthed on Raivavae, one of the southern islands.

As others have pointed out, although the megalithic remains erected by Polynesian settlers do not rule out evidence of an even older civilization, no further investigations have ever been made, which would take months or years. Malden Island is so remote that the cost of getting there and further archaeological exploration is prohibitive. Paved roads lead to the sea, but how far do they extend? Documented observations state that from the center of the island, from which several temple complexes radiate, there is a network of roads made of large basalt slabs, closely united with each other.

These roads cross the island and the beaches as well disappear under the waves of the Pacific. They are very similar to the Ara Metua, a paved road on the island of Rarotonga, 1.000 miles (about 1.600 km, ndt) South. Rarotonga, like Malden Island and others in the Pacific, features a series of pyramid platforms (i Fieldin fact ndt) connected by roads. Strange piles of boulders are scattered around the island of Malden, while the pyramids are covered with dolmen or "compass-stones".

I forty stone temples that can be visited on the island of Malden are described as structurally similar to the buildings of Nan Madol in Pohnpei, approximately 3.400 miles (5.500 km, ndt) of distance. Why such a remote island contains temples, pyramid platforms, and ancient paved paths that lead directly to the ocean is still a mystery. Mitch Williamson, researcher and writer, notes (taking into account the change in sea level through the eras, ndt):

This suggests a culture that could be more than 50.000 years old [...], a civilization that had no problem moving huge boulders to build very large and complicated structures that we know absolutely nothing about, apart from the fact that someone has erect and which are older than biblical history.

In addition, Williamson states:

Sea level has not increased significantly over the past three millennia. If future research shows that the paved paths extend beyond the current shore, then it would have been shown that these relics must necessarily be of pre-Polynesian origin.

Some argue that the roads unraveling from the structures, the purpose of which has not yet been identified, could be evidence of a lost continent that once existed in the Pacific Ocean. The reality is that no one can say for sure. One thing, however, is certain: some mysterious group of settlers made great efforts to build megalithic monuments on an island that could hardly support even a small population.

The various theories could make sense if we place the island and its archaeological relics in a broader geographical and cultural context (such as that of the so-called theory Out of Sumba, which we have talked about elsewhere, ndt).

After all, evidence of lost continents like the Mauritia that were once considered a mere "science fiction" fiction have now also been found by academics, which is why we will never be able to predict if and when new evidence will come to light supporting this hypothesis. In his book Riddle of the Pacific of 1924, prof. John Macmillan Brown he drew an image of the island of Malden with its great pyramidal temples

as a relic of a bygone era, when the latter were still part of a "vanished empire", as well as a place where the ancient settlers came from fertile archipelagos that were located within the chain of Canoe, later submerged by the ocean.