In their new book, "Abraxas: the magic of the drum. The forgotten cult of the cosmic god from shamanism to gnosis", released in March for Mimesis, Paolo Riberi and Igor Caputo investigate the figure of the god / demon Abraxas, halfway between that of the Demiurge of the Gnostic and Platonic cosmogony and that of the aeonic god who connects the various levels of the cosmic manifestation.

di Marco Maculotti

Cover: talismans of Abraxas

Exactly one year ago, in May 2020, I was invited to speak at a conference organized by GRECE, focusing on the occult and esoteric aspects of the most successful TV series of recent years. Among the speakers was also present Paul Riberi, a young Piedmontese writer of whom I had already had the opportunity to review on the pages of "AXIS mundi" Red Pill or Black Lodge, a study on Gnostic influences in and around Hollywood. Certain points of the speech I exhibited that evening, a sort of anticipation of the essay later published by Mimesis, Carcosa unveiled. Notes for an esoteric reading of True Detective (2021), "resonated" not a little to Riberi by virtue of their conceptual proximity to a studio in which he was dedicating time to four hands with Igor Caputo (manager of the "Arethusa" bookshop in Turin), and which would also have been published by Mimesis: Abraxas: the magic of the drum. The forgotten cult of the cosmic god from shamanism to gnosis. Already at the time we agreed to organize one joint presentation of the two works, aired a few weeks ago on the "Stroncature" channel, an occasion on which it was explicitly clarified how the Gnostic doctrines cited by the two authors of Abraxas closely recalled the writer's elecubrations on the "cosmic fatalism" of the first season of Nic Pizzolatto's TV series.

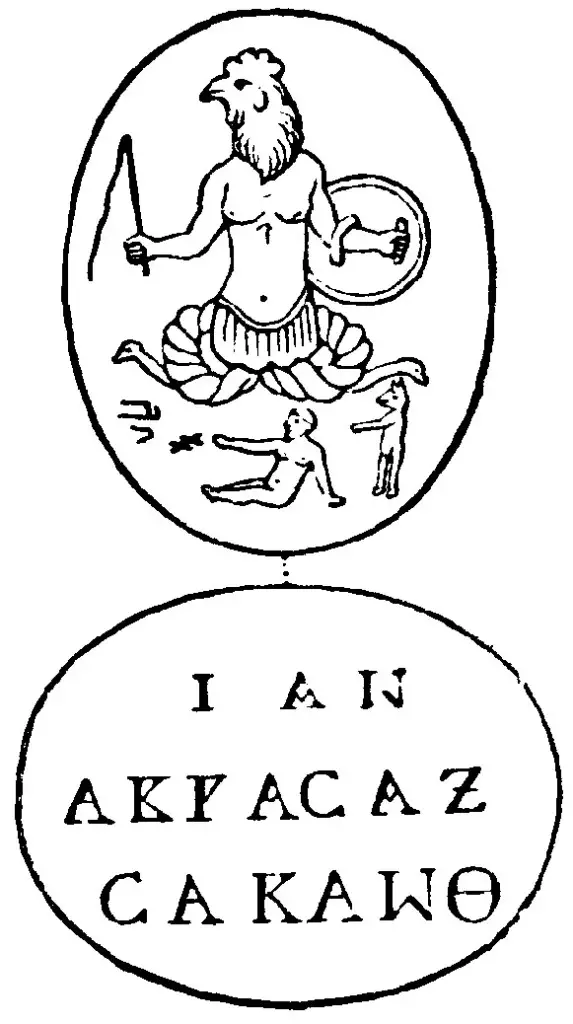

If in Carcosa unveiled the mysterious "King in Yellow" venerated in the eight episodes of the serial by the members of the so-called "Sect of the Swamp", borrowed from the supernatural literature of the late nineteenth century by Robert W. Chambers, was associated by me on one side with some divinities of the cyclic time and the perennial process of death and rebirth through the patrols of the eternal return, such as the Celtic Cernunno or the Mediterranean Saturn / Kronos who was king of the Golden Age and which awaits the return of the same in a state of "life-in-death" confined to Tartarus or variously called "Islands of the Blessed", on the other hand to the Lovecraftian "Great Ancients" and to the "Lords of the Flame of Venus" of theosophical literature, the figure of the enigmatic Abraxas that Riberi and Caputo trace in their new work: the god with the rooster's head and serpentine appendages, invoked by certain Gnostic sects in the centuries immediately preceding and following the advent of Christianity, is simultaneously "Ruler of the celestial spheres" (archon, "Archon"), demiurge of the world of matter, psychopump divinity and messenger through the different levels of cosmic manifestation.

On the one hand, therefore, Abraxas follows the archetype of the "false" god-Demiurge which elsewhere was called Sabaoth and Ialdabaoth and which was mostly paired to the Old Testament god, but on the other hand, for example in the Nag Hammadi scrolls, appears on the contrary in the guise of aeonic manifestation of the God of the Spirit, "Benign divinity, who helps and protects humanity" [p. 38], and which acts as a link between the world of matter and the Pleroma of the Immortals. An ambiguous and at first sight contradictory conception of the god, now heavenly god, now devil, taken up in a rather cryptic but intriguing way by Hermann Hesse in Demian (1919), initiatory and esoteric novel (which is paired with the Steppenwolf, 1927) in which the protagonist is led gnostically from the darkness of ignorance to the light of inner awakening, through the discovery of coincidence oppositorum of the divine entity that governs the plane of manifestation in which humanity finds itself living:

The bird struggles to get out of the egg. The egg is the world. Whoever wants to be born must destroy a world. The bird flies to god. God is called Abraxas [...]

[…] Our god is called Abraxas: he is both God and Satan, and he embraces within himself the light world and the dark world. Abraxas has nothing to object to her thoughts and dreams of him, don't forget them.

It has already been noted by other scholars such as the Abraxas del Demian of Hesse is affected in the first place by the portrait of the god that he drew a few years earlier Carl G Jung. Riberi and Caputo cite an excerpt from his gods Septes Sermones ad Mortuos ("Seven Discourses to the Dead") and highlight the influence that in turn Albrecht Dieterich exercised on the Jungian conception of Abraxas, described as "the" supreme god "of the universe, a symbol of harmony and reconciliation of opposites" :

Abraxas is the Sun, and at the same time the eternal sinking of the Void, of what diminishes and dismembers, of the Devil. The power of Abraxas is twofold: you do not see it, since in your eyes the opposites inherent in this power cancel each other out. What the sun god says is life. What the Devil says is death. But what Abraxas utters is that venerable and cursed word which is life and death at the same time. Abraxas speaks truth and lie, good and evil, light and darkness in one word […]. He is the Fullness making itself one with the Void. It is the Holy Wedding […]. God dwells in the sun, the devil in the night. What God draws from the light, the Devil rejects in the night: but Abraxas is the world, its production and its disappearance.

[pp. 142-143]

However, Abraxas by Jung and Hesse are only mentioned at the end of the work, in the fourteenth and final chapter. In the previous thirteen, the analysis of the two authors develops from a more traditional perspective, making extensive use first of all of the original sources (chapters 1-5), such as the doctrine of Basilides and the now known and already mentioned apocryphal gospels of Nag Hammadi (among which they are cited The Apocalypse of Adam and The Zostrian Apocalypse) and other Gnostic papyri such as the Book of the Great Invisible Spirit o Gospel of the Egyptians. In our opinion, this is the most compelling part of the work, in which certain conceptions are brought to light that historically developed close to the centuries that saw the advent of the Christian era, and which in fact most often interpenetrate with the more "heretical" and "esoteric" teachings of the Savior of Nazareth, or of his disciples. We report in full an extract from the second chapter of the work under analysis here:

But what exactly did this "cosmic secret" consist of, which Jesus would reveal only to a few disciples? The fortunate discovery of numerous apocryphal gospels and the indirect testimonies of the Fathers of the Church allow us to answer this question with good certainty. According to the Gnostics, since his birth man has been an unconscious prisoner in a virtual and corrupt world: what surrounds us is an illusory and decadent realm, where everything is subject to a cycle of change, corruption and death. Everything transforms, deteriorates and, in the end, dissolves into nothingness: it is an inexorable law, which applies both to living beings and to inanimate objects. Consequently, the creator god of the earthly world - worshiped by the Jews with the names of Yahweh and Sabaoth - would actually be a cruel and mad impostor, who keeps humanity locked up in this virtual prison only to be able to enjoy his sufferings forever. . Suffering that, on closer inspection, derive from the very matter that permeates this prison, by its nature subject to decomposition and death. For the Gnostics, the god of Genesis he is a Demiurge, that is a craftsman who, unable to create life from nothing, has given shape to his projects starting from the primordial mud of Chaos: the result, of course, is a corrupt and imperfect world. Combining the two divine names of the Old Testament, the apocryphal gospels call it Yaldabaoth. The boundaries of his kingdom are represented by 7, 10 or 365 celestial spheres that rotate ceaselessly around the earth subjecting it to a constant cycle, represented by the continuous succession of days and seasons. The spheres are ruled by a host of demon-jailers who serve the Demiurge: the Archons (from the Greek archòn, "Governor"). Their task is to prevent man's escape from prison in every way, beyond the eternal cycle of destruction and reconstruction of matter. Beyond the celestial barriers there is another world, made up of pure Spirit: it is the Pleroma (from the Greek plèRome, "Fullness"), otherworldly dominion of the true God. Unlike the earthly world - which is a constantly changing reality, subject to a cyclical path of continuous transformation - the divine Pleroma is immobile and invariable, and exists outside of time itself . Here matter does not exist: nothing changes and everything is perfect and eternal. It is evident that in the Gnostic myth the dualistic contrast is very strong: there are two worlds (the Earth and the Pleroma), the substances (matter and the Spirit), the gods (the false Demiurge and the true God) and even natures of man. Each individual is in fact made up of a shell of raw material and a spark of Spirit, two principles in eternal conflict with each other: the primordial instincts, pain, disease and mortality come from the body, while self-awareness comes from the Spirit, intellect and rationality. The "intermediate ground" between these two opposing poles is represented by the individual soul, the seat of feelings. But what is a spark of Spirit imprisoned in a body in the earthly realm doing? The one hidden inside man is a fragment of the true God, mysteriously precipitated on earth and remained caged in matter. This spark has lost his memory and, along with it, his divine powers as well. There gnosis it consists precisely in awakening from this condition of oblivion: man, who follows the secret teachings of Jesus, can recover the memory of his divine origin and the awareness of his own superiority over the Demiurge, that is, the false god of the Old Testament: " He made me know a word of Knowledge about the eternal God and the fact that we were similar to the Eternal Great Angels: in fact we were superior to the (false) god who had shaped us and to the powers that are together with him. " According to the Gnostics, the Father of whom Jesus speaks is not the angry Demiurge Yahweh of the Hebrew Bible, who punished Adam and Eve, sent the Great Flood, destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah and led the people of Israel into war, punishing them several times in case of disobedience. On the contrary, the "Son of God" of the apocryphal gospels is a manifestation of the true Lord of the Spirit, coming from the celestial realm that lies beyond the confines of our prison world. It is to him that the spiritual self of the Gnostics will return after death, escaping the jailing demons - the Archons - who, instead, try to send souls back down, in a continuous cycle of reincarnation wanted by the evil Demiurge Yaldabaoth.

[pp. 22-24]

These are doctrines that obviously were minorities since ancient times, understandably condemned as heretics and blasphemous by the central ecclesiastical power over the centuries, up to the most absolute destruction of its followers: think for example of the massacre that took place in the XNUMXth century of the Cathars / Albigensians, who professed a faith in many respects "gnosticizing", centered on separation from the Manichaean aftertaste between the god "of this world" and that of the kingdom of the Spirit.

But, from another point of view, these doctrines also recall, as rightly pointed out by the authors, the Platonic explanations of mystery of reincarnation andanamnesi, of the ascent post-mortem of the soul to Hyperuranium to its almost ineluctable "fall", generation after generation, into the sublunar world of matter and suffering, identical in all respects to theGnostic image of the Earth as a "cosmic prison", with the Archons (planetary governors) in the role of jailers placed under the directives of the divinity that Plato himself, in harmony with Gnosticism, defines Demiurge (even if, as the authors note, "unlike the Gnostic Demiurge, that of Plato was a god which tended to good and drew inspiration from the otherworldly "; p. 27).

Think above all of the famous "Myth of Er", which among other things conveys an absolutely para-shamanic conception of the cosmos ("[...]" the concentric spheres of the heavens rotate around a spindle like a vast spindle whorl. Each sphere is associated with a siren (Bird Goddess) who sings its own particular note, thus originating the music of the Spheres", A symphony that keeps the universe in balance"; p. 105), which is said to manifest itself on several levels, governed by their respective spirits or "planetary rulers", comparable to the Archons of the Gnostics and to the otherworldly powers that the disembodied soul encounters on its way to the Hereafter in ancient texts such as the Bard Thodol Tibetan and the Egyptian Book of the Dead:

During the coma, Er would have witnessed the eternal cycle of souls, whose memory is erased after death and then a new life begins in another body. It is the same process described in the apocryphal gospels, from which the Gnostics try to escape in every possible way by ascending their "divine spark" beyond the various celestial spheres.

[P. 27]

With these premises we can therefore understand the reason why, at the time, Riberi saw more than one point of contact between the mindset of the Gnostic worshipers of the "cosmic god" Abraxas and that which holds the entire narrative structure of T as analyzed in the essay by the writer Carcosa unveiled. The synchronicity of which we were protagonists at the time goes to the point that the themes and archetypes on which our respective latest essays are based are essentially the same: think for example of the cosmic and "fatal" framing of the "lost Carcosa", placed under the otherworldly lordship of the enigmatic and terrifying King in Yellow, al "Cosmic fatalism" of the characters of the serial (in primis) Rust Cohle, Gnosticizing mentions of the "Chronic curse" of existence and the "life trap", to the rustic vision of planet Earth as a "big garbage dump" suspended in space, to the obsessive longing of a definitive escape from the patrols of the eternal return to finally reach Eternity, and so on.

Suggestions, these present in the first season of T, which, in principle, the two authors briefly mention at the end of the work, but which are also present here and there behind the surface of the text in various points of the essay. One for all, the “saturnine” framing of the god-Demiurge of the Gnostic cosmogony, especially in the cosmological vision of the Ophites (also exhibited in Carcosa unveiled, pp. 140 et seq.):

Yaldabaoth, a fusion of the biblical names of the Hebrew God Yahweh and Sabaoth, is the Demiurge who rules the seventh heaven and, from there, all the lower levels as well. In confirmation of his animal ignorance of him, he is represented with the likeness of a donkey. In all the maps of the universe, the Demiurge and the seventh heaven are always associated with the planet Saturn: in Greco-Roman mythology it is the kingdom of Chronos, lord of time. "Ialdabaōth - observes the historian Ezio Albrile - is the first and last Archon, in whose features we can recognize" Time ", Aion o Chronos (understood which Kronos, Saturn, the last planet). Not by chance, Saturn appears associated by the Gnostics to the Hebrew God YHWH, considered the head of the Archons because the seventh day, the Sabbat or Saturday, was consecrated to him ”. Moreover, for a man of the first centuries after Christ, the association between the heavens and time was intuitive: the passage of hours, days, months and years was marked by the movement of the stars that revolved around the Earth, and Not vice versa. The ruler of the seven intermediate heavens, also holding control of the celestial gates, allowed the stars to pass through them regularly, allowing them to rotate. In doing so, in fact, he "created time". Only in the earthly world does the law of cyclicality apply, which marks the rhythms of days and seasons, the movement of the stars and even that of souls, which continue to reincarnate in a new body, without stopping. The world of the Spirit, placed beyond the seven moving heavens, was instead fixed and immobile, and therefore "existed out of time", in a condition of permanent eternity.

[pp. 54-55]

The central chapters of the essay (6-8), and later succinctly the 13th, analyze Abraxas in relation to the "magical world" of amulets, gems and talismans and of the invocations written on them, of which he was a great protagonist for a handful of centuries. On the one hand, Riberi and Caputo note the iconographic connection, as the undersigned already hypothesized in one study cited here by the authors [pp. 67 et seq.], With other equivalent divine figures such as the Phanes of the Orphics, theAion of the Hellenic cosmological tradition and Zurvan akarana of the Persian one; on the other hand they hypothesize para-shamanic elements, pushing themselves to recognize in the object that Abraxas would wield not a shield, as is usually thought, but also a "frame" drum of the type used in central and northern Asia to "shamanize" (tambourine). This is probably the most original and "sensational" hypothesis advanced in the essay, discreetly supported by evidence and clues that lead us to reconsider an iconography that was now considered consolidated (usually the presence of the "shield" is justified by describing the cult of Abraxas as initially spread among the legions of Roman soldiers stationed on the limes imperial).

The authors, in addition to emphasizing the connection with the Asian shamanic tradition stricto sensu, they also recognize a "Persian connection", citing some allusions to the visionary and ecstatic journey of the magic operator in the pages ofAvesta [p. 80] and assuming the functional duplicity of the drum, which would also act as a "Sieve" of souls, "Filter between life and death" [p. 90]:

Even in the holy book of the Persian religion, theAvesta, there are undeniable traces of shamanism: among the various stories, the myth of the helmsman Pāurva, hurled into the sky by a bird while he was intent on making a sacrifice in honor of the aquatic goddess Anāhitā, is particularly curious. The unfortunate sailor would have remained suspended halfway between heaven and earth for three days, until the saving intervention of the divinity, invoked with supplications and promises. As the French historian Philippe Gignoux observes, in the course of the myth Pāurva is always accompanied by the epithet vifra-, that is, "trembling", "vibrating": the allusion, not too veiled, is to the spasmodic convulsions that typically preceded the ecstatic journey of the shaman. Even the figure of the bird is not accidental, as it was precisely this type of animal that raised the shaman beyond the borders of this world.

[P. 80]

Here begins the second "macro-investigation" developed by Riberi and Caputo in this essay. If the first part of the book is completely focused on the conception gnostics of the cosmos, in this second part the focus is placed on the "musicological" aspect of the cult of Abraxas, with references to the practices of shamanism and more generally to ecstatic and mystery cults (the case of the processions of the adepts of the give Mater Cybele, also represented in the act of holding a drum; cf. pp. 105-109).

The following chapters (9-12), in fact, develop the discourse on the importance of the drum (or other similar musical instruments, designed to create a repetitive "sound carpet" to the point of obsession, which can favor the detachment of the soul from the body of the experiencer and therefore give him the possibility to perform "astral flights") within the sacred rituals, also citing ex multis the example of the ancient Salento festival of Torrepaduli, characterized by the repeated rhythm of the tambourines, which allows bystanders to completely lose the sense of pain and fatigue and the "consciousness of the present moment" [p. 100], thus realizing the proverbial "level break" of eliadian memory:

Not surprisingly, Mircea Eliade found that in some shamanic cultures of Central Asia the place of the drum was occupied by a rudimentary stringed instrument or a single stringed bow, while in the pre-classical Greek world it was the zither of Orpheus a perform a similar function. In the Africa of the Great Lakes it is the rattles, built with dried pumpkins and filled with seeds, which allow the crossing of the veil that separates the earth from the world of spirits. In fact, the key factor does not consist in the performance of a specific tonality or in the use of a particular instrument, but in a rhythmic, repetitive and obsessive practice which - if performed in particular psychosomatic conditions - leads to trance.

[P. 101]

Although the hypotheses are not strange, compared to the first part of the work and to the intermediate one, the setting of some of these chapters may give the impression of not being thoroughly explored, even taking into account the low number of pages in which they develop. , but if nothing else they are more often than not punctual in providing sources on which to deepen the issues just mentioned.

More detailed is the twelfth chapter, where the authors, pulling the strings from the studies of "Sacred musicology" by Marius Schneider, underline how the IAO ceremonial "mantra", usually considered in the "magic papyri" an invocation addressed to Abraxas and more generally to the cosmic and demiurgic god of the Gnostic sects, would be "the magic formula that governs the heavenly doors, located between the world of the Spirit and the kingdom of matter" , as well as «the Ordering verb, that is, the spell with which the cyclical order of the earthly world is then maintained "and" the creative melody [by the god] generated with the cosmic drum "at the beginning of time [pp. 118-119], observations which are followed almost automatically by the comparison with the AUM (OM) of the oriental tradition.

Right: Abraxas as Baphomet

Equally rich is the chapter that closes the work, of which we have already mentioned the double study on Jung's Abraxas and on Hesse's. The reasons of interest, however, do not end here: the authors also draw some parallels between the Gnostic god and the Metatron of the medieval kabbalists, as well as with the "occult god" of the Knights Templar, to reach the "Abraxa" which in theUtopia by Thomas More (1516) is "the original name of the island that will host the flowering of the perfect society after the landing of the mythical Utopo, a civilizing hero who will also give his name to the region" [p. 136] and the grotesque representation of the "governor of the 365 heavens" in Infernal Dictionary by Jacques Albin Simon Collin De Plancy (1863). In closing there is also room for Aleister Crowley and for his personal reinterpretation of the sacred formula IAO (Isis-Apophis-Osiris), in the initiatory novel The biochemical wedding of Peter Pendragon [pg. 146].

4 comments on “Abraxas, or on escaping from the cosmic prison"