The vastness and complexity of Nietzschean thought find a happy synthesis in the evocative symbols of the archer, the bow and the arrow; metaphors that the philosopher often uses in his main writings, so much so that in the Prologue of the “Zarathustra”, one of his first admonitions is: «Woe! The times are approaching when man will no longer shoot the longing arrow beyond man, and his bowstring will have unlearned to vibrate ».

di Beatrice Harrach

Cover: Mongolian knight with bow and arrow, china, XNUMXth / XNUMXth century (Ming dynasty)

He nocks, stretches, hurls: the motto of the “1st Special Operations Air Brigade” perfectly summarizes the fluid, precise and linear gesture of the archer. A hypnotic, repetitive and orderly gesture that distinguishes those who shoot bow and arrow from any other fighter. A gesture that together with the weapon lends itself to the strong and evocative symbols of royalty and conquest. The archer, who stands on this side of his target - although often very far from it - is already stretched out in the trajectory of his arrow, which will stop where he wanted to shoot it. This, however, provided that he has good aim and, nevertheless, that his bowstring is well stretched. These warlike suggestions must have appeared evocative and effective to philosopher of the superhuman, Friedrich Nietzsche, since he drew from it a veiled figure of a substantial part of his philosophical thought.

The vastness and complexity of Nietzschean thought, in fact, find a happy synthesis precisely in evocative symbols of the archer, bow and arrow; metaphors that the philosopher often uses in his main writings, so much so that in the Prologue of Zarathustra, one of the Maestro's first warnings is: "Trouble! The times are approaching when man will no longer shoot the longing arrow beyond man, and his bowstring will have unlearned to vibrate " [1]. The voice through which Nietzsche sings his philosophy is that of Zarathustra /Ubermensch in which the denunciation of the "dead God" becomes action with the proclamation of the Beyond-man.

In order to conquer the superhuman nature, it is necessary that the inner yearning, the tension of the will, aim beyond man himself. as the archer who draws his bow effectively symbolizes. Nietzsche speaks of a Zarathustra transformed by ten years of solitude, spent near the Sun; hermit in the mountains, nevertheless he became like the sun himself and felt the desire to strike men with his rays, to descend towards them like the great star that sets, setting the anxious horizon on fire. Zarathustra's will yearns for the Sun, Zarathustra becomes Sun; in this way the human will is masterfully represented by the bowstring as the essential means to achieve the goal: only the well-stretched string can shoot the arrow with vigor and power, exactly as only the most indomitable and stubborn will can successfully direct forces towards the goal. For the German philosopher, this image is fundamental: the will has the same tension as the string and the same burning desire as the arrow that craves its target. Zarathustra, transfigured by his ascetic experience, utters words full of will through the metaphor:

"[...] Oh, my will! Every need curves into you, you are my need! Save me from all the little wins! You providence of my soul, which I call destiny! You inside-me! On top of me! Preserve me and spare me for a great fate!

And your last greatness, my will, save it for your last enterprise - so that you may be inexorable in your victory! Ah, who did not succumb to his victory! Ah, who does not darken the eye in this drunken twilight! Ah, to those who did not wobble their foot and did not unlearn to stand firm - in victory!

So that I may one day be ready and ripe in the great afternoon: ready and ripe like incandescent metal, like a cloud pregnant with lightning and a breast swollen with milk:

ready for myself and for my most hidden will: a bow yearning for his dart, a dart yearning for his star:

a star, ready and ripe in its noon, incandescent, pierced, made blissful by the destroying darts of the sun:

a sun and an inexorable solar will, ready to destroy in victory! [...]" [2]

This means, therefore, that in Nietzsche the target (the overcoming of oneself, the objective) struck, does not remain the same as before, but precisely because achieved by the will that had literally targeted it, it is transfigured into something new. , since he was the desire and now, struck, he himself becomes the will of what strikes him, like the star which joyfully becomes itself "Will of the sun" when it is pierced by the rays. Human will is first represented by the tension of the bow, but immediately surpasses itself in the intoxicated flight of the arrow, which very quickly disrupts the goal and, reaching it with immodest strength, fecundates it, making it an expression of its essence.

The symbolism of the arch does not end, however, in the representation of the will. The bow is, in fact, a weapon that by its nature allows you to maintain distance, and this distance is bridged by the arrow. Distance is an aristocratic and distinctive feature. This feature confers a sort of almost moral superiority to the weapon and therefore to the owner ("Tell the truth and know how to use the bow and arrows" [3]), since he does not have to approach his enemy to fight, but can destroy even from a distance, without looking too long into the abyss from which Nietzsche maliciously warns. The peculiarity of the bow, a throwing weapon, also strongly characterizes the archer, making him different from the others, more noble and detached, so much so that Zarathustra proclaims, in the various exhortations to fight, that "Only those who have the arrow and the bow are able to sit quietly: all the others are quarrelsome talkers" [4]. The archer in this sense è truly a warrior - by spiritual vocation - against him who fa the soldier.

The well-stretched string, therefore, leads to magnificent and grandiose results, and only the best, able to draw their bow, would therefore lead to affirm and emerge; it is precisely for this reason that, according to the philosopher, there would have been, on at least two occasions, attempts to "loosen" this rope, in such a way as to make men weaker and more maneuverable. However, tension is a burdensome and difficult condition to tolerate, as is real freedom, which requires great effort to be maintained, therefore, these well-orchestrated attempts would have borne their fruits and weakened the will to power in a rather widespread manner. In fact, we read in Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future:

"Of course, the European man feels this tension as a state of emergency (understood, here, as a burdensome and painful situation, which" alerts "the senses): and two attempts have already been made in grand style to loosen the arc, the first time with Jesuitism and the second with the democratic Enlightenment - such as that which, with the help of the freedom of the press and the reading of newspapers, could actually make the spirit no longer so easily feel itself as an "emergency" ( as something that, in fact, is in tension to emerge)! (The Germans invented gunpowder - all my respect! - but then quickly settled the score by inventing the press.) But we, who are neither Jesuits nor democrats nor Germans enough, we good Europeans and free spirits, very free - we still have it all, the emergence of the spirit and all the tension of its bow! And maybe even the arrow, the task and, who knows? The goal…" [5]

The concept is reaffirmed, once again through the image of the arch, underlining the devastating contribution of "Jesuitism" to the spirit, especially on those exceptional and aristocratic spirits who by their nature rise from the "mass", since "The worst and most dangerous things a scholar is capable of come from the instinct of mediocrity typical of his lineage.: from that Jesuitism of mediocrity that instinctively works to the annihilation of the exceptional man and tries to break or - even better! - to loosen any taut arches. That is, loosen it with care, with the hand that saves, of course - "loosen" with confidential pity [...]" [6]. The slack rope appears to be beneficial to the spirit at first, like a captivity that caters for basic needs, however that lost ideal and volitional tension can, however, be regained through solitude, overcoming oneself, abandoning interest in common opinion, certainly caressing in its promises. Approaching the philosophy of Nostro requires a certain familiarity with the harshness of pure and strong air, and with the highest peaks: in its Ecce Homo Nietzsche himself recalls that:

"Anyone who can breathe the air of my writings knows that it is an air of the peaks, an air forte. You have to be born to breathe that air, otherwise you run the risk, not a small one, of getting cold up there. The ice is near, the solitude immense - but what peace illuminates things! how you breathe freely! how much of the world we feel under our!" [7]

When a soul has inhabited "other mountains ", is unbearable to most: "Un bad I became a hunter! See how hard my bow is drawn! It was the strongest who stretched it to such an extent, but now woe! He is dangerous this dart, like no dart - Out of here! For your salvation ..." [8]. And therefore, since the conquest of a higher will brings horrible scandal to those who do not have the strength to tolerate the fruitful tension produced by the will, it is necessary to become aware of one's diversity, of what one has become: archers, terrible hunters for many who they abandon us:

"Do you turn back? - O heart, you endured enough, hope remained strong; keep the doors open a new friends! Abandon the old ones! Leave the memory! If you were young one day, now you are young better! […] O noon of life! Second youth! O summer garden! Restless happiness of standing and looking and waiting! Friends look forward, day and night ready, where are you friends? Come on! It is time! It's time! " [9]

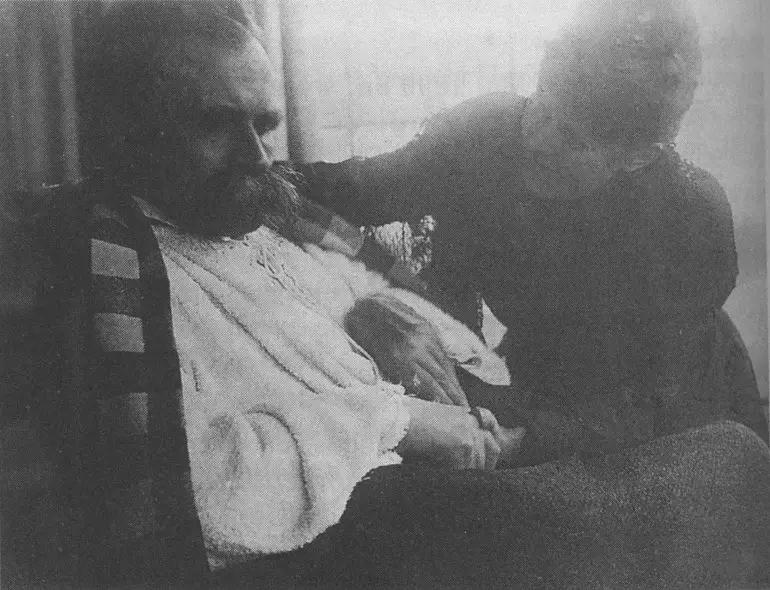

The glorious youth, Nietzsche, took her by pushing beyond man and beyond himself, shaking with implacable enthusiasm the string of his bow, hurling many "sentences and arrows " to darken the sky. Yet who knows to what extent he had to strain his will, when even the muscles of his body began, like nerves of a bow to stiffen hard, to tense in the extreme paralysis that, on 25 August 1900 he finally led him to shoot his last burning arrow in the mystery of Death.

Note:

[1] NIETZSCHE F., Thus spoke Zarathustra, 10

[2] There, 252

[3] There, 64

[4] There, 49

[5] NIETZSCHE F., beyond Good and Evil, 35

[6] Ivi, 159

[7] F. NIETZSCHE, Ecce homo. How you become what you are in Works by Friedrich Nietzsche, 1986 volume VI, volume III, 266-267

[8] NIETZSCHE F., Beyond Good and Evil, 272

[9] Ivi, 272-273

3 comments on “Nietzsche, the archer, the bow and the tightrope of the will"