In this exhibition we will try to compare the main characteristics of the image of the Platonic Cave contained in the VII book of the Republic with those of the Māyā of the Upaniṣads. The common beliefs are evident and involve, above all, the bonds that determine the state of man's imprisonment and the possibility of redemption through the purification of changing forms.

di Claudius Capo

Cover: Megan Kayleigh Sullivan, Sinbad's cave (concept art for the count of montecristo)

In this brief exposition we will try to compare the main characteristics of the image of the Platonic cave contained in the VII book of the Republic with those of Maya of the texts of the upanisad in the light of hermeneutics rising from body-soul relationship which highlights a strongly similar ontological, epistemological and metaphysical content. The presence of unwritten doctrines (agrapha dogmata) that can be seen within the Platonic dialogues reveals an important debt matured towards thePythagorean teaching. Plato, in some respects, takes up Pythagoreanism by dressing it in a new way, and so some of the Pythagorean thought structures are incubated in his philosophical system.

The Pythagorean influence is decisive in the development of the image of the cave, the mystical-ascetic tendencies indicated by the Athenian philosopher, in ascent process from the depths of the cave (anabasis), they seem to confirm this. Although present in the Platonic dialogues, the mystical tradition is decidedly foreign to the Greek thought of the origins. In fact, also for this reason, the doctrine of Plato together with that of Pythagoras breaks with the rationalistic and humanistic tradition of naturalist philosophers who, before them, had largely concentrated on contents of a physical nature. L'mystical aspiration, understood as that experience that pushes the individual towards the conversion to the intelligible, seems to be a peculiar feature of the nature of the philosopher described by Plato.

With regard to upanisad, the marked propensity to problematize questions of a philosophical nature, does not overshadow the role that mysticism plays in the process of "conversion of the soul": just as in "Pythagorean" Platonism the two dispositions - the philosophical and the mystical - coexist and involve each other each other. However it is mysticism that acts as a litmus test to free oneself from the deception of the phenomenal world and to permanently dissolve the link with Maya. This term generally indicates the world of appearances and their illusoryness. The common beliefs, between this and the image of the cave, are evident and involve - above all - the bonds that determine the state of man's imprisonment and the possibility of redemption through the purification of changing forms.

The image of the Platonic cave seems to be substantially superimposable to the Upaniṣadic doctrine of Maya. In the course of the discussion we will proceed by highlighting the similar contents present in the two representations under analysis. Whether or not we accept the hypothesis of a specularity between the Indian thought of upanisad and the “Pythagoreanized” Platonic one, we cannot avoid noting an important number of convergences. Convergences that are so close as to authorize us to consider them expressions of the same conception of the world, so much so that we can use one system to interpret the other.

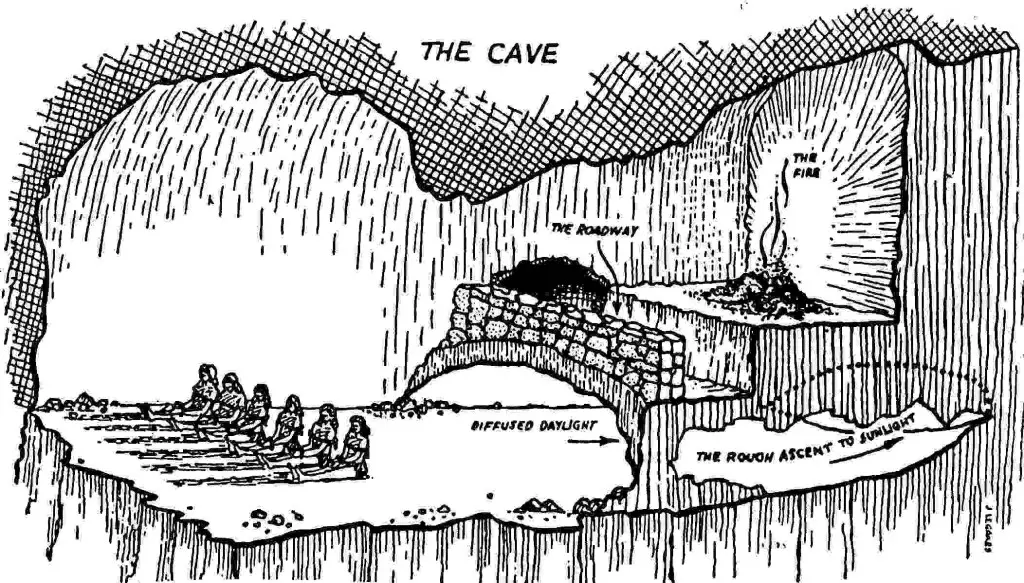

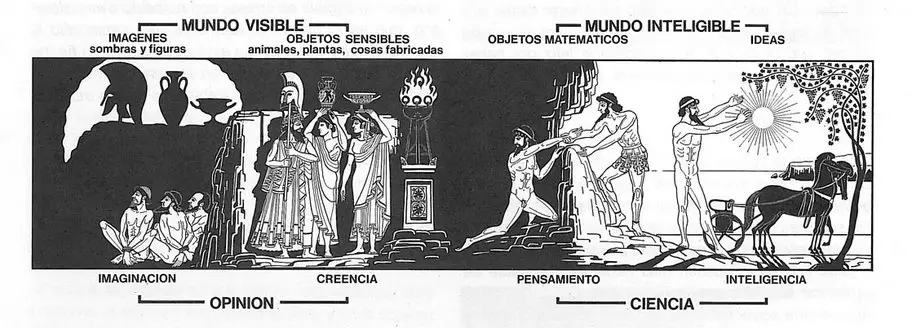

The Platonic Cave and its Pythagorean and Orphic influences

The image of the cave is undoubtedly the allegory that most of all determines Platonic thought in the onto-epistemological sphere. For Heidegger, understanding the myth of the cave means understanding the history of the essence of man [1]; but to fully understand the image of the cave it is necessary to relate it to the images of the Sun and the line contained in the sixth book of the Republic. In line theory the enormous difference between the world of opinion is sanctioned (doxa) and the world of truth (episteme); while the image of the Sun it will represent the idea of Good, the principle towards which everything tends and everything transcends, which cannot be fully expressed even by we. Plato, in the image of the cave, translates the meaning of these concepts to the allegorical dimension and invites Glaucone to a real thought experiment.

One of the crucial points of the philosophy that characterizes Platonic thought, the verticalism, consequence of the existence of two worlds: the world of Ideas and the world of things. The first is the world of archetypes of perfect ideas and stable and immutable values, of which the material manifestation is a copy. The underworld it is presented as an evanescent and imperfect image of that of Ideas which acts as a paradigm or metaphysical model of things. We live in a world that is the incomplete and insufficient copy of the hyperuranic world described in Phaedrus [2]. However, Plato suggests, with knowledge one can go back from the world of appearances to the world of truth. From this point of view, the construction of the image of the cave intends to clarify the characteristics of the two worlds and to mark the process of asceticism of the soul towards the intelligible.

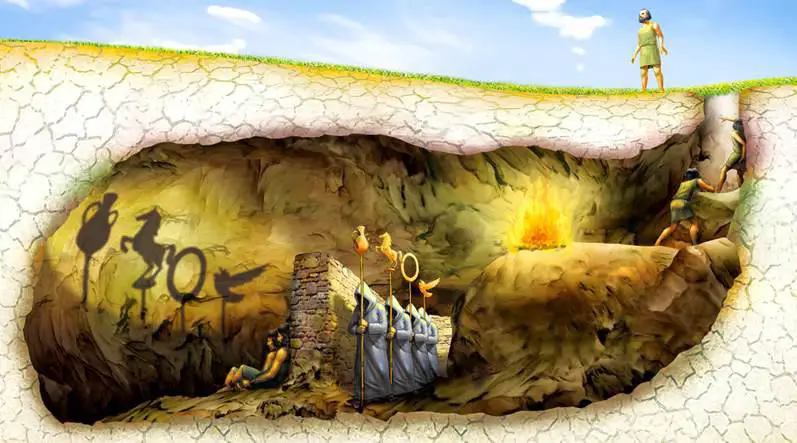

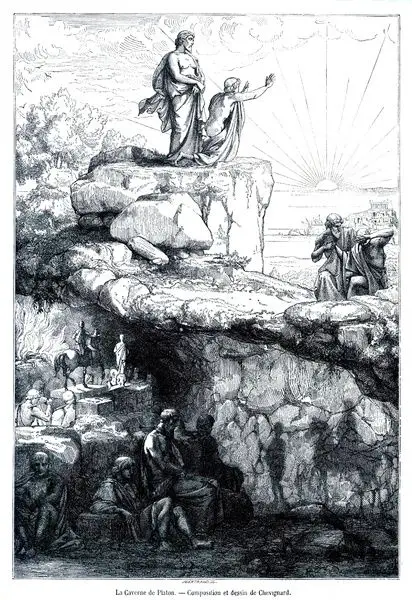

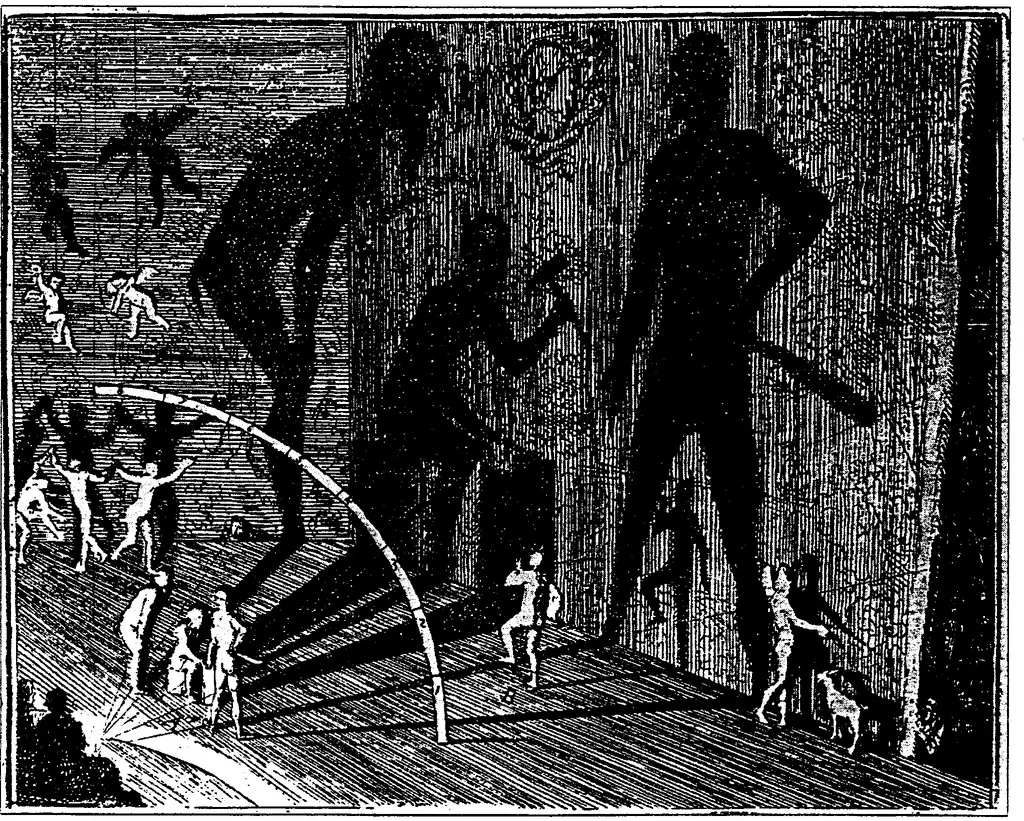

The scenario inside the cave describes men locked up in an underground house who find themselves, since childhood, chained in such a way as to preclude them from any movement and force them to look only in front of them. Behind a low wall, placed behind and higher than the individuals, is the The fire through which the shadows of the silhouettes of the simulacra that determine the objects of knowledge of the scenario are projected on the bottom of the cave. Socrates states, in response to Glaucon, that the men in chains inside the cave are "similar to us" [3]. This statement is decisive for tracing a parallel between the prison condition of the cave dwellers and the human condition determined by the lack of education (apaideusia). The story continues by exposing the progressive ascent towards the light of the prisoners and the vision of intelligible realities. The sudden release (exaiphnes) of the prisoner from his original condition is a necessary but not sufficient presupposition for the final act of liberation, this, in fact, must be obtained through the gradual adaptation to a world - that of the surface - totally new.

“And at first, he will be able to see the shadows more easily and, after these, the images of men and other things reflected in the waters and, ultimately, the things themselves. After that he will be able to see more easily those realities that are in the sky and the sky itself at night, looking at the light of the stars and the moon, rather than during the day the sun and the light of the sun. "

[4]

Outside of metaphor it can be said that the liberation of the prisoner represents the soul that frees itself from the world of opinions and fixes itself, through the knowledge of the noumenal reality, in the objective world of truth. Man is a prisoner of opinion because he passively believes in images of sensible things, that is to say, he takes the shadows of the shapes projected on the cave wall as an object of knowledge. However, the condition of the prisoners chained to the bottom of the cave is a condition of "almost" naturalness (para physin) and does not in any way represent the natural condition of man which, according to Vegetti's interpretation, is given by the prescriptive and normative sense that this assumes: that is to say in terms of a reference to how things should be and in fact they are not since the natural condition of men is that in which they reach the highest level of perfectibility [5].

Even if the prisoner freed himself and observed directly i puppets let go behind the low wall it would be linked to the provisional nature due to the ongoing motion of these. This would see yes objects more real because they are equipped with more be, but it would still be conditioned by entities that have an ontological share that is not sufficient to determine true knowledge, the epistemological one. At the moment of his exit from the cave, man passes to glimpse objects and men directly in the reflection of the water, consequently expanding his perception of reality.

Ma it is only when the soul's gaze turns to the light of the celestial bodies and identifies itself with wearriving definitively in the world of pure understanding, which leads to the contemplation of the Idea of Good, here the process of purification of the soul appears to have been completed. The image concludes by describing the descent process (katabasis) of the liberated in order to exhort the prisoners to make his own conversion to the light. The things that we grasp with the senses are physical forms, empirical data, what we grasp with the eye of the soul are the intelligible forms, the pure essences. The work of liberation of the soul therefore consists in merging into the world of Ideas and identifying oneself in reality.

The reference to the practices of purification, the belief in the immortality of the soul and the need to lead a life of purity to free oneself from the false opinion of things: these are just some of the characters present both in the Orphic-Pythagorean tradition and in Platonic philosophy - especially in the dialogues of the philosopher's maturity such as the Phaedo , Republic. The Orphic doctrines that are accepted and developed by Platonic thought are those of metempsychosis, of immortality and of divine nature of the soul, of the bonds that bind the soul to the body and the possibility of redemption through purification. A simple reference to the Orphic and Eleusinian mysteries will help us to better understand the Pythagorean background that conditions the elaboration of the cave image and to outline the profile of "Platonic mysticism". Although there are differences between the Orphic cults and the Pythagorean doctrines, here, only "shared spaces" will be considered.

There is a close correspondence between Orphism and the teaching of Pythagoras, so much so that he considered Orpheus the first of his tutors. With the term "mystical", in Eleusinian initiatory mysteries, the experience by which the soul reaches its maximum degree of perfection is delineated. This experience is obtained at the end of a progressive detachment from sensitive knowledge - in the most radical cases the detachment even involves intelligible knowledge - up to the loss of dualism between the experiencing subject and the experienced object - it should be remembered that for Plato the fundamental character of the Idea is that of unity and of how the nature of the philosopher is manifested precisely in knowing how to grasp and possess this unity. Since one cannot give thought other than "thought about" or "thought of" something, such an experience suggests an earlier form of consciousness and in a certain sense different from the ordinary one. He tells us Kerényi:

«Man's experiences do not always and not immediately produce thoughts. From them can arise imaginaries, and even words, which have not necessarily been preceded by thoughts. Man was already re-elaborating his own experiences even before he was a thinker. Language reflects pre-philosophical notions and re-elaborations of experience which are then taken up and developed by thought. "

[6]

Dionysus he is the god of worship; the cornerstone of Orphic religion is the belief in the intrinsic immortality of the soul. The liberation of the divine from the non-divine elements is the goal of the Orphic cults. In the phenomenon ofecstasy the soul "comes out of the body" and reveals its nature in the same way that the prisoner frees himself from the chains and exits the cave.

The elements described above represented the pulsating core of all Pythagorean thought; it is thanks to the influence of this that Plato seems to have come into possession of these doctrines. For Plato Pythagoras he is an example of a teacher who exerted a strong influence on the life of his disciples [7]. Penetrating deeply into Pythagorean thought it becomes clear how the universe is not seen only as an order based on respect for proper proportions; this is characterized by a "harmony": it is a being in agreement with all things. The human soul must also try to imitate the order of the universe.

Several times Pythagoras, like Plato, will relate the microcosmic dimension with the macrocosmic dimension of existence. For the sage of Samos, just as the universe constantly tends towards harmony - the highest degree of perfectibility, so the ultimate goal of man is pure contemplation, the perfecting of human nature. Pythagoras traveled a lot, studying the doctrines of the Egyptians, Assyrians and Brahmins. It is from the latter that he seems to have learned the doctrines with which he will try to "awaken" his disciples.

A comparison between the Platonic Cave and the Maya of the upanisad

As it suggests Georges Dumezil in the elaboration of his theory on tripartite structure of the Indo-European peoples, there is a close resemblance between the language, mythology, traditions and social institutions of the Indians and the Greeks [8]. In light of this, it is not entirely out of place to assume that the Olympic religion and Vedic beliefs have had a common origin and that, at the time of their contact, numerous symmetries have re-emerged. The upanisad they contain the main coordinates of all Indian thought and within them some of the same principles can be found that we find exposed in allegorical form in the image of the cave. The Indian texts tell us that the supreme wisdom lies in knowing the Self which, like the Platonic intellect, folds in on itself to isolate itself from the phenomenal world and contemplate the world of the Absolute (brahman).

Reality, both for Plato and for Upaniṣad, it is not knowledge of something, but knowledge of the thing itself. The ordinary act of knowing presupposes that there is a knowing subject who superimposes his own consciousness on the known object, the knower and the known are separated from each other and give life to multiplicity. Precisely from this it is made to proceed the material world which, like Plato, is seen as a "prison of the soul". It should be reiterated, in order not to fall into a misleading Manichean interpretation, that the body-soul dualism upanisad what for Plato is actually apparent: all polarities, not having the One as their domain, represent a partial degree of knowledge. Reality is given by the recognition of the indistinct union of all the elements that, erroneously, we observe as separate from each other.

As in Platonic philosophy, the Upaniṣadic tradition maintains that, to understand reality, an instrumental exercise of reason is not enough: it must be followed by a process of inner purification - Plato will refer to the condition of education, paideia - leading to liberation (mokṣa). As we have previously seen the image of the cave, in the light of the Pythagorean doctrines and under the influence of the Orphic religion, assumes a very specific mystical character. All mystical knowledge includes the experience of the non-reality of everything other than the One. The individual is already in possession of the truth and the function of the teacher - like the Socratic one - is mainly maieutic: to help bring the truth to the light of conscience.

There are many similarities between the cave scenario described by Plato and the ancient Indian texts. Here we will mainly look at the symbolism of the Sun which is proposed by Plato to expose doctrinal aspects of capital importance and which, with the same function, is widely present in upanisad: "The Sun is the truth" [9]; and again «Brahman is the Sun; the Sun is Brahman " [10]. Like Platonism, therefore, truth is close to the Sun; and this, in turn, is identified with the Absolute. The link between purification and knowledge qualifies both the Platonic work and the Upaniṣadic tradition: knowledge (jñana) is opposed to the conception of metaphysical ignorance (avidya) which precludes access to the truth: "Into a terrifying darkness enter those who live in ignorance" [11]; and again "Brahman is reached only with ascesis" [12]. The purification from the sensible world and the passage of the soul towards the intelligible one through a path of asceticism it is conceptually identical to the itinerary proposed by Plato in the cave.

Another important analogy between the Platonic thought exposed in the image of the cave and the upaniṣadica one concerns the distinction of different degrees of knowing: by establishing as a criterion of hierarchization their relationship with the supreme knowledge - the Platonic Good and the upaniṣadic Absolute, the vertical structure of knowledge:

There are two kinds of knowledge a man can acquire. One is the highest, the other the lowest. Those who know Brahman have passed on this tradition to us. " [13]

“It is through higher knowledge that we reach the informal. Divine science reveals to us the knowledge of that reality which transcends the senses, reveals the principle, the uncaused cause of everything. " [14]

It should be borne in mind that even for Plato the Good implies absolute reality, supreme knowledge, going beyond the world of the sensible and of forms and the liberation of the soul: "at the extreme boundary of the knowable there is the idea of good and you can hardly see it, but once you have seen it it must be concluded that it is really always the cause of all that is right and beautiful, having generated in the place of the visible light and its lord, in that of the noetic being herself a lady and dispenser of truth and thought " [15]. Le upanisad, like Platonism, propose a distinction between the intellect which calmly contemplates the intelligible and the intellect which, grasped by the multiple, is determined on the basis of the empirical datum.

Furthermore, it should be noted that the Platonic image of the cave strongly recalls the Upaniṣadic doctrine of Maya. in See this term indicates that force from which the material world originates. However, with the philosophical reflection posed by upanisad, the intuition takes hold that phenomenal reality is by its nature differentiated and partial but that, in some way, it is such only in function of another reality, the Absolute one.. Just as the cave produces shadows that are exchanged as real objects, so does the Maya it separates individual beings from transcendental knowledge by preventing them from the act of liberation. Similarly to the image of the VII book of the Platonic Republic, man is presented as an individual whose intellect, contemplating the world with "the eye of the senses", determines itself in the illusion and becomes a prisoner of it. When he begins to observe the world with the mind's eye (the intellect), he gets rid of the condition of metaphysical ignorance that conditions his perception of reality and his soul awakens from cognitive lethargy and can finally contemplate the ultimate essence of reality.

Conclusions

In this brief discussion we have tried to highlight the mystical aspect that operates behind the scenes of the image of the cave and an attempt has been made to clarify the Orphic-Pythagorean influences that act within Platonic philosophy. A large part of Platonic reflection is indebted to the Orphic religion and the Eleusinian cults; these represent the spiritual humus on which Platonic philosophy was able to carry out its "Pythagorization". This, in turn, has strong similarities with Indian thought of upanisad. The expression of these close analogies are such as to make us think that an attitude that excludes the possibility of an intimate connection between them is idle. Whether or not the hypothesis of a direct influence of Indian thought on the Greek one is valid, whoever dedicates himself to the study of Orphism and Pythagoreanism cannot fail to notice the similarities existing between these schools and Upaniṣadic thought; similarities which - as stated - are so close as to authorize us to consider them expressions of the same conception of life so much so that we can use one system to interpret the other.

The image of the cave and the Maya of the upanisad they seem to be superimposable. The difference in "language" is to be traced, more than on the conceptual and philosophical level, on the historical level. The different articulation of the same doctrine is determined by the presence of cultural contexts and audiences so different that it would have been impossible to express the same contents in the same way. The path to better understand the doctrines hidden within the esoteric content of these two images is still long, the studies still being in their embryonic stage.

The evident historical and cultural limitations discourage the linking of the Greek world with the Indian one, even if it seems evident that these two worlds, in one way or another, met and benefited from each other. However, if the foundations of this relationship could be consolidated on what unites rather than on what separates, we would certainly have the opportunity to look at both the history of Western thought and that of Eastern thought from a different perspective.

Note:

[1] See Heidegger, On the essence of truth, Armando, Rome 2019.

[2] Plato, Phaedrus, 247C.

[3] Plato, Republic VII, 515A.

[4] Plato, Republic VII, 516A.

[5] See Vegetti (edited by), The Republic, BUR, Milan 2006, p. 842.

[6] Kerényi, Dionysus, Archetype of indestructible life, Adelphi, Milan 1992, p. 17.

[7] Plato, Republic VII, 600B.

[8] See G. Dumézil, The tripartite ideology of the Indo-Europeans, The Circle, Rimini 2003.

[9] Bṛhadāranyaka Upaniṣad, V, 5, 2.

[10] Chāndogya Upaniṣad, III, 19, 1.

[11] Bṛhadāranyaka Upaniṣad, IV, 4, 10.

[12] Taittirīya Upaniṣad, I, 9.

[13] Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad, I, 1, 4.

[14] Ibid, I, I, 6.

[15] Plato, Republic VII, 517B.

Bibliography:

Bṛhadāranyaka Upaniṣad.

Chāndogya Upaniṣad.

Dumezil, Georges The tripartite ideology of the Indo-Europeans, The Circle, Rimini 2003.

Heidegger, Martin On the essence of truth, Armando, Rome 2019.

Inge, William The Platonic Tradition in English Religious Thought, in S. Radhakrisnan, Eastern religions and Western thought, Bompiani, Milan 1966.

Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad.

Kerényi, Karol, Dionysus, Archetype of indestructible life, Adelphi, Milan 1992.

Plato, Phaedrus.

Plato, Republic.

Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli, Eastern Religions and Western Thought, Bompiani, Milan 1966.

Reale, Giovanni (edited by) Plato, Republic, Bompiani, Milan 2000.

Taittirīya Upaniṣad.

Vegetti, Mario (edited by), Plato, Republic, BUR, Milan 2006.

2 comments on “The Platonic Cave, its Orphic and Pythagorean influences & the Māyā of the Upaniṣads"