Through the biblical episode of the Akedah, better known as the “Sacrifice of Isaac”, the pictorial cycle of the synagogue of Dura Europos testifies to an identity struggle between pagan and Jewish culture. Furthermore, the passage from Genesis XXII throws light on some instances concerning the foundation of the Temple of Jerusalem, and on the sacrifices that were paid within it.

di Lorenzo Orazi

Cover: David Teniers the Younger, Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac, 1655

Introduction

The biblical episode narrated in Genesis 22, 1:18 is among the most enigmatic passages of the Old Testament, capable of generating an almost endless critical literature. Not only post-biblical texts, writings of the rabbinic literature and of the church fathers, Targum and Midrash, but we will see that within the Bible itself it is possible to recognize a first elaboration of the episode. It is certain that the theme of Abraham's obedience to the divinity who calls him by name has always played a preponderant role in the reading of the episode. Nevertheless the narrative presents a complexity of facets, of implications and details, of linguistic and structural issues, to give us the impression of an impossibility of exhausting all the issues it exposes.

In the Jewish religion the passage takes the name of "Akedaht Itzahk", or "Binding of Isaac". It refers to the Korban Tamid, the sacrifice of a head of cattle, often a ram, paid at the Temple in ancient Israel. We will see later how, in rabbinic exegesis and beyond, a direct lineage is proposed between Genesis XXII and the cult practiced in the Temple. In the Christian religion, on the other hand, the better known name of "Sacrifice of Isaac" immediately betrays the method of typological reading, that is the interpretative practice privileged by the fathers of the church according to which the Old Testament constitutes the prefiguration of the New, which therefore sees in the narration a symbol of the sacrifice of Christ.

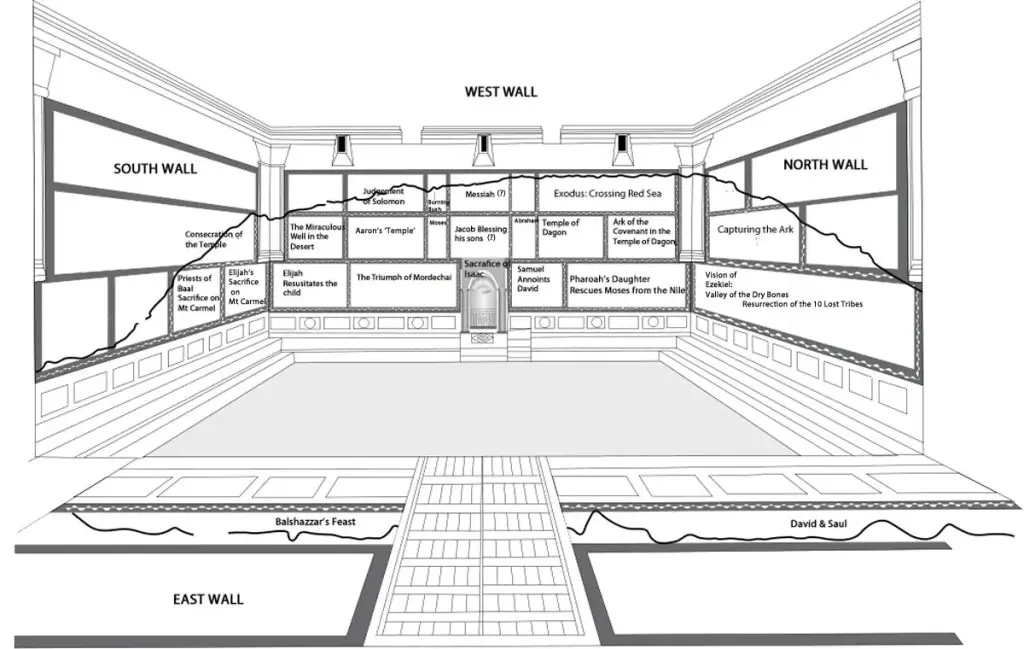

The article proposed here is the excerpt of a three-year thesis with which an attempt was made to understand the images produced by Judaism and Christianity in reference to Genesis 22, 1:18. It was a question of drawing a map of the preponderant themes, and of the ways in which these were elaborated in the exegetical tradition. Specifically for the selected chapter, we will review the circumstances of the discovery of the Synagogue of Dura Europos (Fig. 1,2) and we will provide an overview of the cycle of paintings found inside. The examination will therefore focus on the panel depicting the Akedah and on the interpretations proposed by scholars for the purpose of its reading.

Some argue that the representation intends to exalt the redemptive character of the ram, the liberation of Isaac which took place through him. Others, on the other hand, suggest that the image is emblematic of the cultural dynamics taking place in the city of Dura Europos, where a multiplicity of religions coexist and each of them struggles to affirm its identity over the others. Finally, the iconographic theme of the temple, arising from one of the interpretations taken into consideration, will be analyzed in more detail.

Dura Europos Synagogue

The city that hosts the Dura Europos Synagogue was founded by Seleucus I around 300 BC; conquered by the Parthians, it became an important place of trade between the Eastern and Western world. In the second century AD it came under the rule of the Romans, then it was destroyed by the Persians around 256. In 1932 the scholar Michael Rostovtzeff, and a team from Yale University directed by him, excavating under the embankment of the walls that protected the city from the desert area to the south, unearthed a private house., built in the early third century and transformed very soon, probably around 232, into a place of Christian worship [1].

The excavations continued and, a few months later, still in the vicinity of the surrounding walls, another building was found, of which, through the inscriptions and representations discovered inside, they sanctioned the Jewish origin. The expedition was unable to restore and properly preserve the synagogue in situ; the paintings were then detached and the restoration process took place in the National Museum of Damascus, where they still stand today.

Only ten years after the transformation of the private house into a synagogue, that is in 255/6, the Romans covered the building to build a line of fortification, for the purpose of defense against the Persians. This fortuitous circumstance made it possible for the precious pictorial cycle of Dura Europos to reach us. The walls were the indispensable protection for the conservation of the building. The paintings (Fig. 1, 2), in tempera on dry plaster, depict biblical scenes on three registers whose overall meaning is still the subject of debate, and rest on a plinth decorated with clypei, animals and fake marbles. The east wall is particularly damaged, it is not possible to suggest which biblical episode it refers to except as a hypothesis. In the first level of the north wall is represented the vision of Ezekiel and the consequent resurrection of the dead.

Continuing to the left, on the west wall, there is the rescue of Moses from the Nile by the daughter of the Pharaoh; below the anointing of David by the hand of Samuel. We are at the core of the west wall: the Ark of the Torah is dominated by the episode of Genesis 22; above, two particularly damaged scenes leave strong doubts to the interpretations. The first shows two figures lying on sofas: one is surrounded by twelve figures, the other by only two. Rostovtzeff [2] he hypothesizes that there may be two versions of Jacob: in the first case surrounded by the twelve sons, in the second while he blesses Ephraim and Manasseh. Above the scene of Jacob a man sits on a throne, possibly King David surrounded by a host of servants. Around the particularly damaged central nucleus, there are four characters, each isolated in its own frame. These are four fundamental moments in the life of Moses: Moses and the burning bush, Moses on Sinai, Moses reading the scrolls of the Law, and Moses after his death, surrounded by the sun, the moon and the stars.

Returning to the first level, after passing the niche of the Torah, there is the representation of King Ahasueros and Mordecai, triumphant on a white horse. The last scene of the west wall and the two survivors of the south wall illustrate episodes from Elijah's life: first with the widow of Sarepta, then on Mount Carmel in two different episodes. Beyond these scenes the south wall is heavily damaged and offers only pictorial fragments.

In the second register, starting from the north wall, we find the capture of the Ark of the Torah by the Philistines, which took place in the battle of Eben Ezer. In the following scene, the first frame of the west wall, the Ark is taken to the Dogon temple, to be then reconquered by the Jews who lead it back to their temple. Beyond the central core, always on the second level of the west wall, is the scene of Aaron in the Temple and, below, Moses making water gush from the rock. Only fragments remain of the southern wall. The third level is the most damaged: illegible to the north and south, it retains fragments in the west wall. In addition to the scene of the enthroned character previously analyzed, an image depicting the crossing of the Red Sea survives.

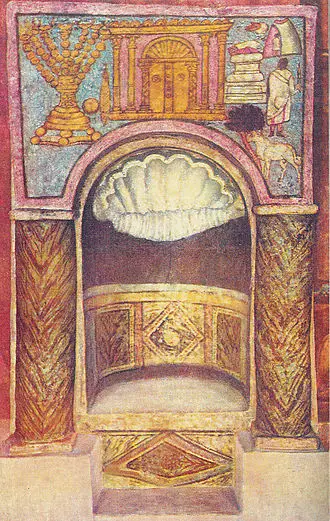

Having provided a general description of the pictorial system, it is now possible for us to analyze with greater attention the image that refers to Genesis 22. The representation of the Akedah (Fig. 3) is housed, as we have seen, in the arch above the shrine of the Torah, that is the Holy Ark. This is the main site of the whole synagogue. Located in the center of the west wall, facing Jerusalem, it is the direction in which the faithful address their prayers. The image was originally made as a decorative part of the structure, and is the only surviving testimony of it. Originally ornamental motifs dominated, while representations of animals and men were excluded; the Akedah episode was unique. It can help to understand its importance to know that, of the previous cycle, it is the only one maintained and never modified.

In the left area the symbols of the Sukkot stand out (also known as the Feast of Booths or Feast of the Tabernacle). This is the menorah, or the seven-branched lamp; the iulav, a palm branch; and the etrog, a cedar. The temple is represented in the central area and the Akedah on the right. In the foreground there is a ram near a plant: the preponderant position highlights the importance that the artist intended to accord to the figure. It is reasonable to assume that the reference text was the Hebrew one in which, unlike the LXX, it is specified that the animal was behind Abraham's back [3].

The patriarch, seen from the back, raises his right hand and holds a knife; Isaac is crouched on the altar; above him the hand of God appears and, next to this, a curtain is depicted that houses a small figure, interpreted as the case may be as a servant of Abraham, Ishmael, Sarah or Abraham himself. The way in which the three human figures are represented testifies to a certain embarrassment in the treatment of such a subject; it will have been noticed, in fact, that none of the three faces is shown to us. If, as we have seen, the figurative episode constitutes an exception to the first pictorial period of the structure; it is equally true that we have not yet freed ourselves from the fear that, through the representation of man, we can fall into the sin of idolatry, thus transgressing the law reported in Exodus 20,2: 17-XNUMX.

According to the interpretation of Ruth A. Clemens [4], the image as a whole places the accent on the liberation of Isaac. The scholar hypothesizes an internal narrative structure that unravels from the back, where the figure in the tent would recall the episode of Genesis 18. It tells of Abraham who, sitting at the entrance to his tent, raises his eyes and sees three men: God came to communicate to him the forthcoming birth of Isaac, through which his descendants must spring. Continuing, Clemens identifies in the central part of the scene the moment of crisis of the promise; or when, close to the sacrifice, it seems that the pact is about to break. In the end, the central value entrusted to the ram certifies the fulfillment of the covenant, which occurs through its substitution for Isaac.

Clemens' reading, although it has the ability to provide plausible reasons for the peculiar composition of the image, and is also the only one to justify the presence of the curtain and the mysterious figure on the threshold, seems to lack something. The author, in fact, decides to free herself not only from the general pictorial context of the synagogue, but also from the panel itself in which the Akedah scene is housed; as she does not take into account, nor does she provide explanations, the image of the temple, first of all, but not even the symbols of the Sukkot.

Judaism and paganism

Jas Elsner [5], through an interpretation capable of keeping together the complexity of the pictorial system, tries to trace a map of its unitary motifs, to the point of connecting it with the cultural reality of the city of Dura Europos. The author believes to identify in the cycle a strong recurrence of anti-pagan themes and, consequently, of an exaltation of the Jewish religious belief. This phenomenon can be traced back to the plurality of cults typical of the Greco-Roman world, where each religion undertook dynamics of identity self-definition. The decorations of the sacred spaces do not escape this mechanism: methods of sacrifice, clothing, rituals, everything that distinguishes one cult from another is used as an affirmation of one's belief.

Specifically, the Dura Europos synagogue [6], this is manifested so much in the emphasis and in the multiple examples of representation of the temple, of the ritual objects and of the Ark of the Covenant; as in the sacrifice scenes that the building houses. As for the first point, the author takes into consideration the image of Aaron in the Temple (Fig. 4), scene also known with the name of "Consecration of the Tabernacle", and the one immediately to its left, that is the image of Moses making water gush from the rock, placed on the west wall, to the left of the Ark of the Torah. They are images in which particular importance is given to the place of worship, to ritual objects and where the stories of important fathers of the faith are narrated.

An image on the right of the Torah casket responds to these scenes, located, in a mirror image of them, on the opposite side of the wall, where it is represented the Ark of the Covenant in the Dogon temple. The scene is introduced at the corner of the north wall with the Battle of Eben Ezer which, developing from right to left like the Hebrew script itself, leads to the episode that interests us most. In the battle the Philistines defeat the Jews, and steal the Ark from the enemy to take it to the Dogon temple (Fig. 5); however, once it arrives in the pagan temple, the Ark causes the statue of the God to fall and destroy. Finally, we see the Ark embarking on the journey on a chariot, pulled by a pair of oxen, to return to the Jewish temple.

Elsner believes that in these images there is a harsh criticism of the pagan religion. If in the episodes of Aaron and Moses an exaltation of Judaism, of its objects of worship, of the patriarchs and of the temple is proposed; in the scene of the Dogon Temple we see the pagan place reduced to shatters, its idol destroyed and the religious furnishings scattered on the ground. As for the sacrifice scenes, Elsner takes into consideration the two paintings of the first level of the south wall, and the same scene of the Akedah. In the left image of the couple (Fig. 6), the priest of Baal fails in his attempt to invoke the fire that should have burned the ox placed on the altar. In the niche in the center of the altar stands Hiel. According to Jewish legend, he tried to light the fire manually, but was killed by a snake sent by the Lord.

In the image on the right (Fig. 7), Elijah is near an altar on Mount Carmel and invokes fire from Paradise, while four young people carry amphorae full of water to make the miracle more difficult to carry out. According to Elsner, in order to decipher the pictorial program of the synagogue, and the meaning of these two scenes in particular, it is essential to relate them to the panel that houses the representation of Genesis XXII. Here, again, the importance of the temple is emphasized. Accompanied by the figure of him, we also find the Menorah and the objects of the Sukka. But what matters most, according to Elsner, is the repudiation of the human sacrifice that the Akedah presupposes. If in the two scenes of the south wall the success of Elijah in carrying out the sacrificial rite is shown, in spite of the pagan priest of Baal who, unable to invoke the sacred fire, fails in his purpose; the fresco of the Akedah sanctions a definitive departure of the Jewish religion from human sacrifice. Through the imposition of the divine will, which substitutes a ram for Isaac, the sacrifice can be consummated in a declared separation from the ancient cult.

Elsner's research can be considered an echo, as well as the application to the field of the figurative, of pioneering essay by Shalom Spiegel [7], dating back to 1967, in which the author investigates the survivals of the pagan within the Jewish tradition. Analyzing the passage in which the midrash of Rabbi Yudan (a text of biblical exegesis) deals with Genesis 22, Spiegel believes he sees the persistence of an ancient formula. The plea is made to Rabbi Benaiah, and he informs us about the idea of the replacement sacrifice:

“Master of the whole universe, behold, I am slaughtering the ram; do Thou regard this as though my son Isaac is slain before Thee [..] "

It would belong to a historical moment far from that in which the rabbi writes, when the transition from human to animal sacrifice was taking place. Spiegel argues that the supplication could date back to three votive stems found in Algeria, belonging to the period between the end of the second and the beginning of the third century BC, the same period in which Rabbi Benaiah lived. The formula had the function of a solemn plea, proclaimed in order to appease the divinity, asking her to accept the substitution with favor: the soul of the lamb for the soul of man, the blood of the lamb for the blood of the man. Spiegel believes that, at the time of Rabbi Yudan's midrash, the pagan heritage had not yet been forgotten. Only with a gradual development will the influence of those laws soften, and the new generations will learn to replace man with an animal, no longer afraid of having practiced an imperfect sacrifice. The lines with which the author concludes the analysis deserve to be cited in full:

"It may well be that in the narrative of the ram which Abraham sacrificed as a burnt offering in place of his son, there is historical remembrance of the transition to animal sacrifice from human sacrifice - a religious and moral achievement which in the folk memory was associated with Abraham's name, the father of the new faith and the first of the upright in the Lord's Way. And quite possibly the primary purpose of the Akedah story may have been only this: to attach to a real pillar of the folk and a revered reputation the new norm - abolish human sacrifice, substitute animals instead. " [8]

Spiegel, in a second moment, returns to the theme of the encounter between paganism and Judaism. This is the ceremony of Rosh Hashana, the Jewish religious New Year also known as "Remembrance Day". It is the time when God proceeds to consult the history of humanity in order to decide who will be worthy of forgiveness and who will not. Following the ten penitential days, culminating in Yom Kippur, it is played the Shofar, or the ram's horn [9]. This practice has its origins in ancient cults connected to the birth of the new moon, when the sound of the horn was to serve to ward off evil forces. In Jewish worship, the sound of the Shofar is freed of its pagan matrix and acquires a new meaning: according to the Torah, it has the task of remembering the Akedah before God, and thus invoking mercy for the day of judgment.

The temple

We have seen that the unity found by Elsner is given as the need of the Jewish community to draw its own portrait. In this process the representation of the temple acquires a central value; Let us therefore pause for a few moments on this iconographic theme and on its relationship with the episode of Genesis XXII. In the Masoteric Text, in verse 2 of the passage narrating the Akedah, God orders Abraham to go to the territory of Moria to carry out the sacrifice. Within the biblical text, only in another passage is mention made of the same mountain. This is 2 Chron. 3,1, where it is stated that Solomon built the temple right on Moria. Also the Book of Jubilees [10] (18,13:XNUMX), indicates the place to which Abraham and his son are led such as Mount Zion, another name for Moria.

This circumstance, in addition to demonstrating that the episode of the Akedah is subjected to a critical reading within the Bible itself, confirms the willingness of the authors to establish a link between the Akedah and the main place of worship of the Jewish religion. It should be remembered that the temple was the setting in which the Korban Tamid, or the daily offering of a head of cattle, was practiced. Several sources testify to the commitment of the fathers of the Jewish religion to trace a lineage of the Korban Tamid from the original sacrifice taught by Abraham [11].

The significance and actual geographic location of Moria became the subject of numerous speculations by the rabbis. It is generally believed that the name derives from the Hebrew term לראות †, that is "see". The topos of the vision remains central in most of the exegetical texts, which are based on v. 22.14, commonly translated as "On the mountain the Lord provides" or, in the case of the Septuagint, "on the mountain the Lord was seen" [12]. On the temple mount the Lord is particularly present as the people of Israel offer you the Korban Tamid. In the Old Testament there are two privileged places for the manifestation of God: first of all Sinai (Exodus 34 9-11; 1Ki 19 9-18), and secondly Jerusalem (2Sam. 24 15-17; Isa. 6.1; Ps. XlVIII, esp. Vv. 5.8 [Heb. 6,9]). Since Genesis XXII speaks of a place within the central territory of Israel (three days' journey from Beersheba), it can be assumed that it is precisely in Jerusalem that a Jew of that period would have spontaneously thought [13].

In the Targums, Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible, it is asserted that Abraham's vision justified the construction site of the temple on Mount Moria. Pseudo-Jonathan, for example, calls the place where Isaac was bound as a "mountain of worship" [14]. Again, on the theme of the vision, it should finally be remembered that Spiegel considers it necessary to relate the affirmation "on the mountain the Lord provides" (v. 22.14) to the arrival of the ram: the Lord provides to find a substitute for the offering, such as, on the other hand, it was already predicted by Abraham when questioning his son (v. 8). It is by virtue of this replacement that a lineage is established between the place of Genesis XXII and the Temple of Jerusalem [15].

Note:

[1] Rostovtzeff M. (1938); Dura-Europos and its art; Oxford, Clarendon Press, Great Britain 1938; pp. 158-162

[2] Ibid, p. 168-170

[3] Kessler E. (2004), Bound by the Bible: Jews, Christian and the Sacrifice of Isaac, University of Cambridge; p. 165

[4] Clements RA (2007) The parallel lives of early Jewish and christian texts and art: the case of Isaac the Martyr; in New approaches to the study of biblical interpretation in judaism of the Second Temple Period and in Early Christianity; Proceedings of the eleventh international symposium of the Orion Center for the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls and associated literature; Edited by: Gary A. Anderson, Ruth A. Clements and David Satran; Brill, Leiden / Boston, 2013; pp. 225

[5] Elsner J. (2001), Cultural Resistance and the Visual Image: The Case of Dura Europos; Classical Philology, Vol. 96, No. 3 (Jul., 2001), pp. 269-304; Published by: The University of Chicago Press 2001

[6] Ibid, p. 181

[7] Spiegel S. (1967), The last trial: on the legends and lore to the command to Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice; Jewish lights publishing 2007, pp. 61-68

[8] Ibid, p. 63

[9] Ibid, p. 74-76

[10] The book of Jubilees; Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, 1917; Trad. Eng. Charles RH

[11] Fitzmyer JA (2002), The sacrifice of Isaac in Qumran literature; Biblica, Vol. 83, No. 2 (2002), pp. 211-229; Published by: Peeters Publishers; p. 215

[12] Op. Cit. Kessler E. (2004); pp.

[13] Moberly RWL, The Earliest Commentary on the Akedah; Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 38, Fasc. 3 (Jul., 1988), pp. 302- 323; Brill; pp. 6-7

[14] Op. Cit. Kessler E. (2004), Bound by the bible: Jews, Christian and the Sacrifice of Isaac; p. 87

[15] Op. Cit. Spiegel S. (1967), The last trial: on the legends and lore to the command to Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice; pp. 67

A comment on "The sacrifice of Isaac in Jewish iconography"