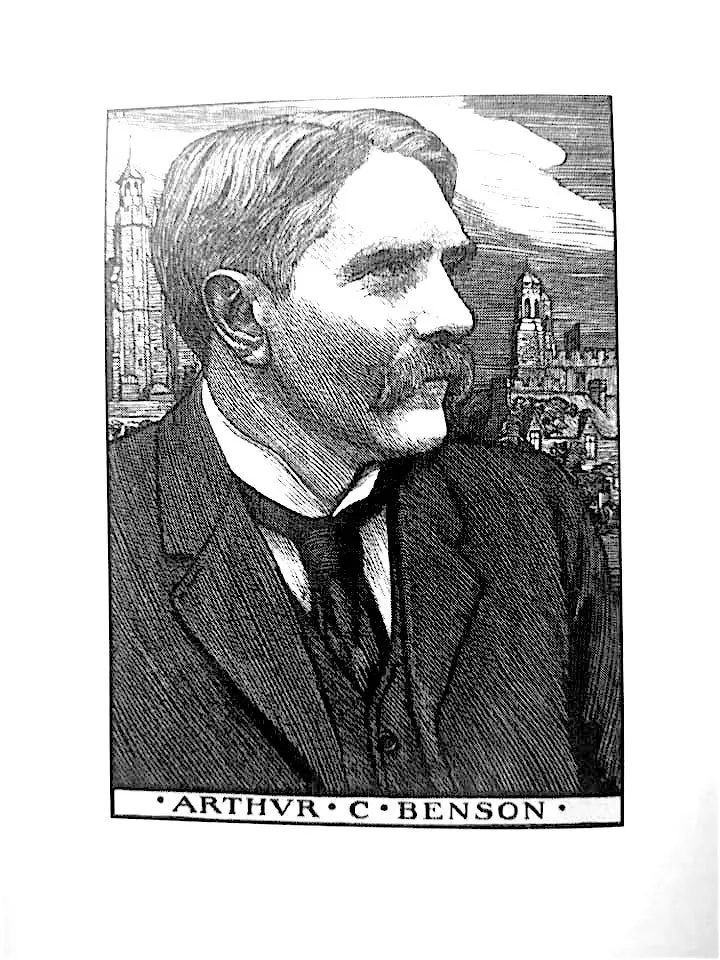

Dagon Press recently published in Italian - with the title "The closed window" (translation by Bernardo Cicchetti) - the supernatural tales of Arthur Christopher Benson, along with Montague Rhodes James one of the most significant "ghost-writers" English of the early twentieth century, as well as comparable in suggestions and themes to writers roughly contemporary to him and equally "esoteric" such as Arthur Machen, HP Lovecraft and Algernon Blackwood.

di Marco Maculotti

There was a time when the 'ghost stories' they were taken much more seriously than they are now and than they have ever been in at least the last century. Those were other times, in which the intellectually and economically dominant social classes expressed themselves through a literary canon entirely different from the current one, which responded to a heterogeneous cultural canon in its components, which incorporated the Anglican and Protestant vision of the world and of sin. together with the supernatural suggestions conveyed in classical studies, mostly medieval. At the end of the XNUMXth century, in full Victorian and then Edwardian age, with a handful of short stories read during a college Christmas get-together, the foremost English writer of ghost-stories, Montagu Rhodes James, completely revolutionized the genre, leaving behind a century of more or less spurious gothic novel and more psychic than actual ghost stories.

A prodigious medievalist and expert in miniatures, as well as later rector of King's College in Cambridge, MRJ anticipated HP Lovecraft by conveying in his ghosts much more than the mere unsolved souls of the disembodied - a perspective that on the other side of the Atlantic saw excel. Ambrose Bierce -, revealing them instead epiphanies of ancient demons, astral survivals of black magicians, damned spirits of perverse intelligences that now only partially can be defined as human. MRJ's 'ghosts' almost always exhibit abnormal physicality, hideously liquefied features like in the movies gore by Lucio Fulci; not infrequently this 'deviated' physicality is configured as a spy for one regression to chaos which led, as in Great God Pan and The Inmost Light di Arthur Machen, from the human form back to forgotten atavisms, which in the stories of MRJ now take on characteristics typical of arachnids (The Ash Tree), hour of the batrachians (The Haunted Dolls' House), and even forerunners of the tentacular nightmares of Lovecraftian memory (The Treasure of Abbot Thomas).

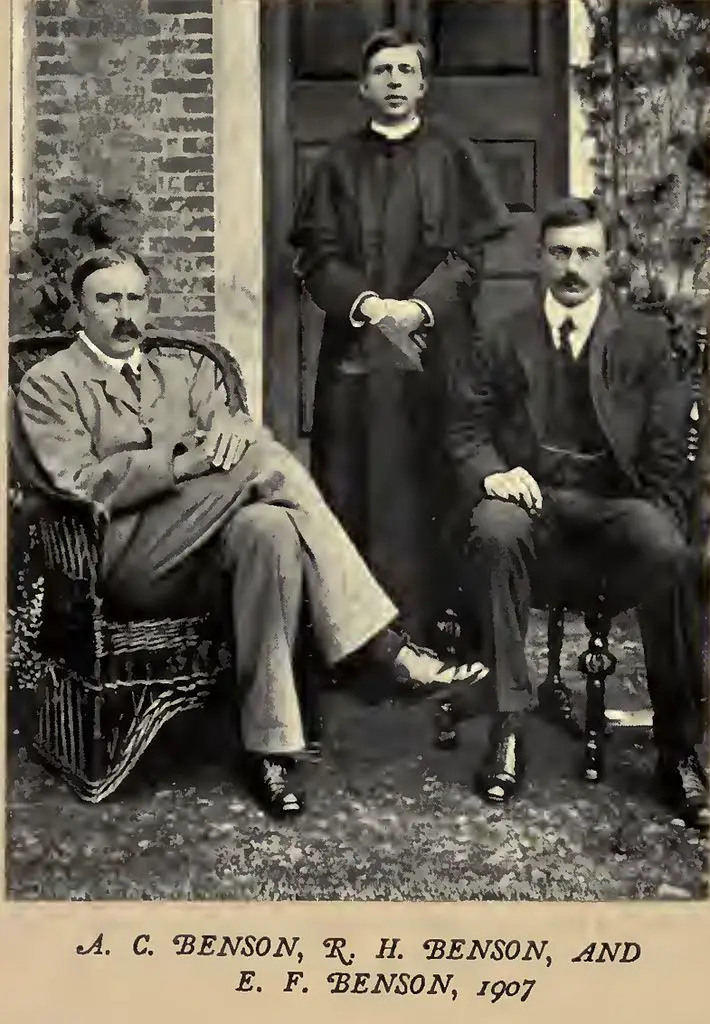

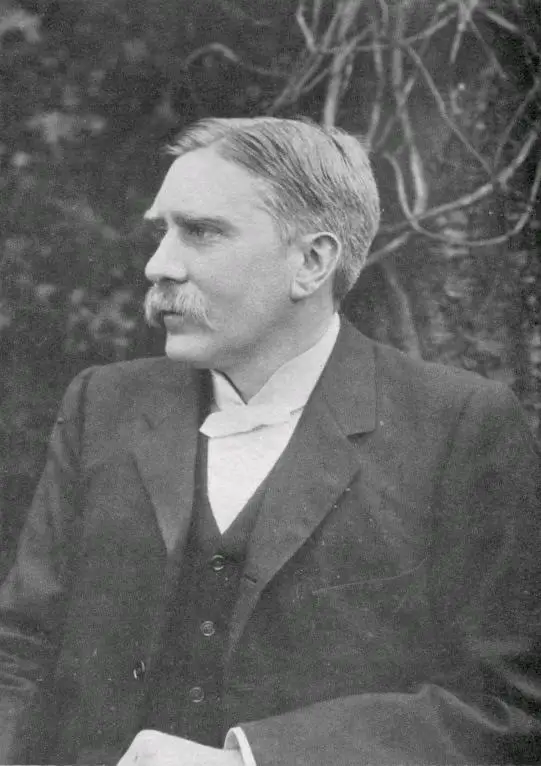

Today, however, we do not intend to speak of MR James, which we have already discussed in the past on our pages, but of Arthur Christopher Benson (1862-1925), who was a colleague and close friend of the former, finding himself living in his own era and sharing with him the predilection, in the narrative field, of the form of the short story to express that type of 'uncanny' suggestion which, in their view, almost always resulted from an overflow into our ordinary world of powers of nature totally other compared to the human being. Benson, who devoted himself to writing his black 'short stories' in the last decades of his life, was also friends with another James, The famous Henry author of Turn of the screw, in whose house he lived and who mentored him by encouraging him in writing. But Pietro Guarriello, impeccable as always, rightly emphasizes in the afterword as in the Benson family ghosts were at home, considering that ghost-stories her father also wrote her success Edward White Benson (1829-1896), archbishop of Canterbury, also founder of one Ghost Society which later became the Society for Psychical Research, as well as Arthur's two younger brothers, Edward Frederic (1867-1940) and Robert Hugh (1871-1914).

As in the works of Machen and Lovecraft, also in MR James and AC Benson's 'ghost stories' the Chaos coming from the invisible dimension strikes down on the everyday life of the unfortunate protagonists, plunging them into terror, and perhaps in the latter even more than in the former the 'chosen victims' must mainly curse their intellectual curiosity that leads them step by step as condemned to the gallows: in almost all the stories, the characters of MRJ and ACB destined to fall into the whirlpools of horror approach of their own will, in an almost obsessive way, to certain mysterious places and objects, burdened by sinister legends, paradigmatic expressions of a supernatural and magical world which, although evoked in the Victorian and Edwardian era, does not present a solution of continuity with the folklore of the 'dark ages' of the Middle Ages. One might think that this type of magical thought can hardly be combined with the Anglican and Protestant spirit of the Anglo-Saxons, but on closer inspection it is ultimately their nemesis existing at a subconscious level, the proverbial 'other side of the coin'.

The reason for the 'cursed place' from which the malefic powers, teased, momentarily return to life, typical of the literary production of MRJ, is found in The Red Camp ("The red field"), a story that has remarkable correspondences with different stories of the first (Martin's Close, Wailing Well, A Warning to the Curious). To precipitate events, as in the Lovecraftian The Moon Bog, is the foolish decision of the protagonist to reclaim a sinister grove, known for the presence of an ancient fort linked to a legend about a bloody battle and a buried treasure, to extend the pastures of his property. Similarly to the folk-horror nightmares of Machen, the ruined fort, which serves as portal to the Other World (once excavated, it is compared to "an ugly scar on the green hill"), it is located inside a ancient burial mound, seat of the disembodied spirits in the Celtic tradition; and as in certain tales of the Welsh (Novel of the Black Seal), it refers to the "history of the ancient races that had inhabited the earth" to shed light on the mystery of the fort in the Red Field. Indeed, more than the Anglo-Saxon tradition, "The red field" seems to be more inspired by the Scotus-Irish and Welsh one, to the point that certain statements by the canon seem to be taken on an equal footing from the treatise of the Scottish counterpart Robert Kirk on Secret Commonwealth of elves, fauns and goblins, written at the end of the seventeenth century and published for the first time in 1815 (by Sir Walter Scott) and a second time in 1893 (by Andrew Lang): it is therefore probable that Benson, as a lover of British folklore , had consulted this source before writing his own Red Camp.

I topos of 'fairy hill'and 'dark forest' he was born in 'treasure to find 'are also found in The Snake, the Leper and the Gray Frost ("The snake, the leper and the gray frost"), which however clearly stands out from the other tales of this collection by virtue of the different stylistic register used. It is in fact the most anomalous story of the collection, a sort of Quest-Fantasy much more flavor fairy tale that disturbing, and at the same time undoubtedly initiatory (Traditionally, fairy tales have always conveyed initiatory truths). You mention the 'door' that appears on the side of the hill and then magically disappear, al Missing Time typical of folk tales from all over the world concerning access to the Other World and finally to the large presence of corpses on the place of the 'passage' (a common motif in the Iranian and Siberian tradition) are spies of Benson's sincere passion for ancient traditions, local and otherwise.

The 'ghost' of Out of the Sea ("From the sea"), placed at the opening of this collection, distances itself considerably from the anthropomorphic model: it is described as "An evil beast that comes from the sea", "dark and shapeless", "horned and hairy", which drags behind a repulsive stench of salt and corruption, eyes "narrow and obscene", animated by an opaque yellow flame. Like the invisible demonic agents of some of James' most famous tales, for example Oh, Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad e A Warning to the Curious, also 'degenerated psychic residues' di Out of the Sea they are almost imperceptible to the sight of the one who awakened them, who can only glimpse them out of the corner of his eye ("I can never see it clearly; it's like a stain in the eye ... it's never there when you look at it ... it slips away from hidden"). Reason that is also found in The Slype House ("Casa Slype"), where the "strange thing" is "pale and horned, very confused", a story based on a figure typical of MRJ and then also dear to HPL, that of the enigmatic outsider who lives in a sinister mansion, spending its secluded existence

in malefic research on the dark secrets of nature […] and on many other occult works of darkness, such as relations with evil spirits and the black influences that await souls.

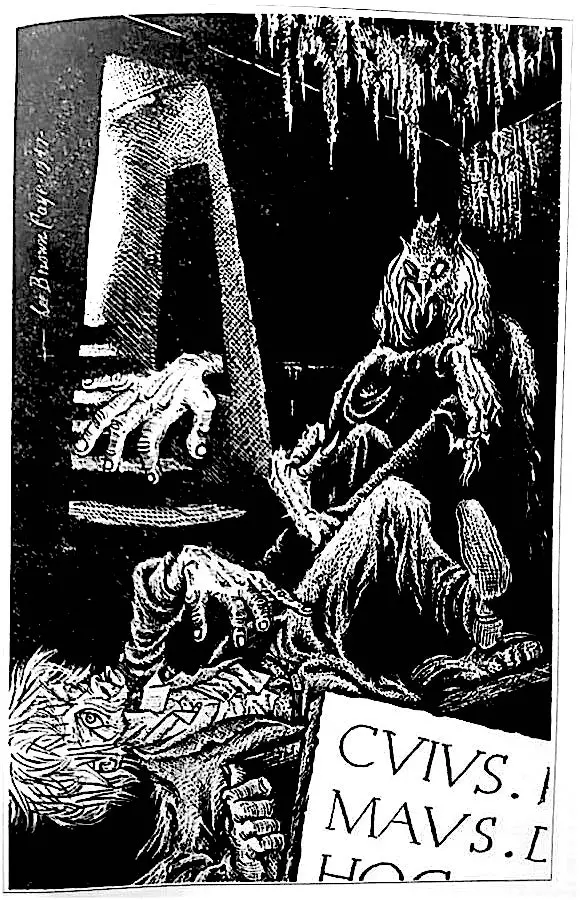

It partially detaches itself from the other stories The Temple of Death ("The Temple of Death"), a dark adventure set in the times of wars between the Gauls and the Romans which in certain passages seems to anticipate the more 'epic' current of Weird literature of the first half of the twentieth century (Robert E. Howard, Clark ashton smith), not to mention even the famous Lovecraft's 'Roman dream', which unfortunately, despite its considerable potential, was never translated into a real story. The whole story revolves around the arrival of the Roman Christian preacher Paullinus at one of the many 'cursed places' of Benson's fiction, the so-called 'Temple of the Gray Death', where the priest - partly inspired by the Rex Nemorensis of which Frazer - would practice unspeakable rituals to satisfy the terrible divinity of which the temple is a tabernacle. The latter presents itself immediately as a terrifying epiphany of the cuckold Cernunnus - in many respects analogous to Bread which experienced a second rebirth during the Victorian era - recalled in the text in the description of a "horned and bearded head, deformed and grotesque", analogous to the mask of Dionysus or of Silenus in the Mediterranean tradition. On the other hand, it is clear that the god venerated in the thick of the wood presents strongly 'panic-Dionysian' tinges, to the point that he is presented in these terms by the priest who practices him:

The god who created these great solitary woods, and who lives there, is very different [from Christ, ed]. He loves death and darkness, and the cries of strong and furious beasts. There is little peace here, even though the woods are silent… and as far as love is concerned, he is a brutal kind of love. No, stranger, the gods of these lands are very different and require very different sacrifices. They delight in acute sufferings and agonies, in tortures, drops of blood, sweats of death and cries of despair.

The temple itself, of a megalithic nature, is adorned with "a horrible engraving which to Paullinus seemed the work of devils": characteristics that we find slavishly in the subsequent city of the 'Great Ancients' in the Lovecraftian cycle (At the mountains of madness) and in some Weird novels by Abraham Merritt (Dwellers of the Mirage). The 'demonic' engraving of a 'panic' character, in Benson's story, is almost a forerunner of that of The Red Hand of Machen, depicting "a gross figure, with an evil and lascivious face", which gives Paullinus the impression of being "a servant of Satan, if not Satan himself, frozen in stone."

MRJ and Lovecraft are still the tutelary names that come to mind when reading The Closed Window ("The closed window"), which on more than one occasion recalls two of the most legendary tales of the Solitaire of Providence, namely The Music of Eric Zann e The Haunter of the Dark. At the heart of the narrative is the so-called "Tower of Fear" of Nort, once used by the sinister Sir James de Nort, ancestor of the protagonists of the story, for dark and mysterious occult operations. Following the sudden and inexplicable death of the ancestor, the room at the top of the tower was sealed, but when his descendants set foot again it seems to come alive again with the nefarious presences that had been imprudently evoked in that place, as well as the spirit of man who had brought them into our world.

Typically Gaelic is instead the plot of The Gray Cat ("The gray cat"), one of the best episodes of the anthology, especially for the supporting element of theriomorphic supernatural presence: in the folklore of the Celtic countries, in fact, almost all the entities coming from Elsewhere approach human beings behind the appearance of animals (just think of the example of Kelpie and selkie). On the other hand, the story is set between the hills of Wales and the centuries-old ruins that dot them, and here the 'non-ghost ghost' on duty shows himself to the protagonist knight, as the title suggests, with the appearance of a gray cat. The mysterious entity seems to dwell near the source of a stream, a black and immobile pool considered taboo by the local farmers, to the point of exorcising it every year. All Saints (i.e. a Halloween) with a concert of bells lasting all night. As in the Willows by Algernon Blackwood, the natural element appears here permeated by malevolent if not demonic powers, by something indefinite and yet absolutely palpable "which harbored aversion for the life of men". Similarly, the purely 'feric' themes of the story also derive from Gaelic folklore, such as the 'strange dream' through which the protagonist Roderick is offered to access the hill through an invisible door placed on its side and the elven music that accompanies the event, and again the mention of hawthorn (fairy plant par excellence) and al profound change which took place in his interior after the dream experience - this is a theme that is extensively treated by Do (The Hill of Dreams) but also, in non-fiction form, from Gustav Meyrink (The metamorphosis of the blood).

The two most notable stories of the collection, however, are the concluding ones. Basil Netherby (“The house in Treheale”) would not disfigure at all in a collection of the best short stories by MR James, whose style and suggestions slavishly follows. But it also contains several previews of the best Lovecraft, from the music endowed with "a wild, immoderate voluptuousness" by Netherby, which anticipates the much better known violin of Eric Zann, at the "sudden passage through the trees" that the protagonist finds towards the end, in which "the shrubs were torn, broken and trampled, as if something heavy had overwhelmed them", a detail that seems to surprisingly anticipate the conclusion of Dunwich Horror. Identical is also the sort of Nerherby, who like Wilbur whateley from the beginning he appears condemned to eternal damnation by virtue of his own 'diabolical conferences', which take place thanks to a conduit that connects a low door in the latter's room to a hidden door in the woods surrounding the castle. Basil's own ancestor, like Wilbur's, used to meet "visitors who […] it was not convenient to admit into the house." But, as mentioned, there is also a lot of MRJ - in addition to the story and the atmosphere in general, especially note Basil's remark about his mysterious visitor, namely that he would see him running quickly towards him from "Quite far", similarly to the presence of Oh Whiste. But there are even Machenian reminiscences, especially in discourse on the "perfect beauty of evil", which is paired with the one contained in The White People and ends with these words:

now I understand […] that the evil that hinders humanity is nothing but the mire of the abyss from which it is only gradually emerging.

Closes the anthology The Uttermost Farthing (“The last change”), which also centers on a house that is 'haunted' due to the abominable magical operations that have been performed there in the past. The authors of the comparison are always the same: in particular, as regards the correspondences with Lovecraft, the detail of the plaster stain on the floor is surprising, having "a strange resemblance to the silhouette of a prostrate figure" - it comes to mind The Shunned House - as well as the description of the "entire history of the family" faulkner (a sort of anticipation of the novels of the namesake William, one above all As I Lay Dying, 1930), as "a constant downward journey", a sort of 'atavistic involution' reminiscent of some in equal measure degenerate lineages of Lovecraftian memory and certain characters from Machen's tales. For the rest, a central role is held by the usual revived invisible presences and the never too explicit 'experiments' and 'demonic pacts' typical of Jamesian tales, as well as the belief - which could without problem be read in a Machenian work -

that God is slowly and patiently working to conquer a world where there is […] a strong element of something atrocious and horrible, which challenges Him and takes every opportunity to undo His work.

A comment on "The diabolical conferences of Arthur Christopher Benson"