November 1st is the watershed between one agricultural year and another. At the end of the fruit season, the land, which has welcomed the wheat seeds destined to be reborn in spring, enters the period of hibernation. For Christians, two important feasts are celebrated in these days, All Saints' Day and the Commemoration of the dead. But once upon a time, in the lands inhabited by the Celts, which stretched from Ireland to Spain, from France to northern Italy, from Pannonia to Asia Minor, this period of transition was the New Year: it was called in Ireland Samuin and it was preceded by the night still known today in Scotland as Nos Galan-gaeaf, the night of the winter Kalends, during which the dead entered into communication with the living in a general cosmic mixing, as has already been observed in other critical periods of 'year.

di Alfredo Cattabiani

taken from Calendar, Postal Code. VIII

cover: William Stewart MacGeorge, Halloween, 1911

At the end of October

After the harvest, October declines towards the dark and cold season. The persistent rains begin, which can last for a long time, as the saying of the 16th says: "If it rains for St. Gallen it rains for a hundred days", which is countered by: "It is good in San Gal it is good up to Nadal". time to plow since the agricultural season is ending and the new one is about to begin, so it is said: "Whoever sows in October reaps in June"; or: "Either soft or dry, for San Luca it sows everything"; and finally: «For San Simone, take the ox off the rudder, put the shaft in the spade», because the plowing for this period - we are at 28 - must be finished and also the brave digging. The insects in turn die or take refuge in places sheltered from the cold, so that: «For San Simone a fly is worth a pigeon».

The Catholic liturgy does not provide for solemnities but only feasts of saints, on the 18th the evangelist Luke and on the 28th the apostles Simon and Jude, who do not fall into this journey not having an important calendar function like the other saints mentioned. celebrates the memory, from Saint Teresa of Avila to Saint Ignatius of Antioch. Certainly, encountering such sublime figures in the course of the liturgical year, the temptation to retrace their lives would push us to overturn the dams of this journey to expand it into a majestic series of witnesses to Christ. Once the temptation is overcome, we accompany the month of October in its extinction among the autumn mists in a magical night for the ancients, but perhaps still for us.

All Saints' Day and the Celtic New Year

November 1st is the watershed between one agricultural year and another. At the end of the fruit season, the earth, which has welcomed the seeds of wheat destined to be reborn in spring, enters the period of hibernation: "For All Saints' Day be the grains sown and the fruits returned home" advises a proverb. For Christians, two important feasts are celebrated in these days, All Saints' Day and the Commemoration of the dead. But once upon a time, in the lands inhabited by the Celts, which stretched from Ireland to Spain, from France to northern Italy, from Pannonia to Asia Minor, this period of transition was the New Year: it was called in Ireland Samuin and it was preceded by the night still known today in Scotland as Nos Galan-gaeaf, the night of the winter Kalends, during which the dead entered into communication with the living in a general cosmic mixing, as has already been observed in other critical periods of 'year.

It was a great holiday for the Celts, just as the New Year's solstice celebrations were for the Romans, and it was still celebrated in the early Middle Ages. To Christianize it, the Frankish episcopate instituted the feast of All Saints on 1 November, to which Alcuin (735-804), the authoritative adviser of Charlemagne, contributed above all to spreading it. A few decades later, the emperor Louis the Pious, at the request of Pope Gregory IV (827-844) inspired by the local bishops, extended it to the whole Frankish kingdom. But it still took several centuries for November 1st to become the feast of All Saints throughout the Western Church: it was Pope Sixtus IV who made it compulsory in 1475. The tradition of celebrating all saints, even the unknown ones, was not born however in France. Since the second half of the second century in the East and the third in the West, the Church celebrated every year the anniversary of the dies natalis of each martyr, or the day of his rebirth in heaven which coincided, as has already been explained, with death. .

In Greek mártyr meant witness; and the first of the martyrs, the model, was Christ himself, "the faithful witness", as John called him in the Apocalypse, who nevertheless gave the same title to Antipas, killed in Pergamum for his faith [1]. It was certainly not a contradiction since the martyr who confesses his faith in Christ to the extreme sacrifice becomes one reality with the Risen Crucifix and gives the Father the same witness of fidelity that the Son gave him: son in the Son, in the mystery. of heavenly communion. In the first centuries the martyr was remembered at his tomb with the celebration of the Eucharist. Initially we prayed to the Lord for him, then we began to pray to him, to consider him an intercessor with God, as evidenced by the Roman graffiti of the Memoria apostolorum dating back to around 260. The custom of celebrating each martyr in his dies natalis induced the local Churches to compile a list with the date of death and the place of deposit of the body, or rather of death, as prescribed by St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage (died in 258) [2]: so that from the middle of the third century the first sketches of the Christian calendars and martyrologists were born.

The first depositio martyrum we have received is contained in the aforementioned Philocalian Chronograph (354), so called because it was composed by Furio Dionigi Filocalo, Greek artist and inventor of characters of rare elegance which he would later use to have sculpted on the tombs of martyrs the inscriptions dictated by his teacher, Pope Damasus. The Chronograph, which was intended for a Christian, as evidenced by the dedication (Floreas in Deo, Valentine: may you flourish in God, Valentine) contains in the first part a calendar with the Roman glories, followed by the seven days of the week with their properties astrological; in the second, the consular fasti, the catalog of the prefects of the city, the description of Rome and finally some Christian texts including the depositio martyrum with the essential indications: for example, on the third day from the Ides of August, that is to the 11th, we Law Laurenti in Tiburtina, or Lorenzo on Via Tiburtina. We report it below, putting the translation into modern dates of the Roman ones in brackets:

item depositio martyrum (December 25): VIII Kal. Jan. Natus Christus in Bethleem Judeae.

Canteens Januario (January 20): XIII Kal. Feb Fabiani in Calisti et Sebastiani in Catacumbas.

(January 21): XII Kal. Feb Agnetis in Nomentana.

Canteens Februario (February 22): VIII Kal. mart. Christmas Petri de catedra.

Mense Martio (7 March): Non. Mart. Perpetuae et Felicitatis, Africae.

Mense Maio (May 19): XIV Kal. jun. Partheni et Calogeri in Calisti, Diocletian IX

and Maximiano VIII cons. (304).

Mense Junio (June 29): III Kal. Jul. Petri in Catacumbas et Pauli Ostense, Tusco et

Low cons. (258).

Mense Julio (10 July): VI id. Jul. Felicis et Filippi in Priscillae; et in Jordanorum

Martialis, Vitalis, Alexandri; et in Maximi, Silani; hunc Silanum martyrem Novati furati

sunt; et in Praetextati, januari.

(July 30): III Kal. aug. Abdos et Sennes in Pontiani, quod est ad Ursum piliatum.

Mense Augusto (6 August): VIII id. aug. Xysti in Calisti, et in Praetextati, Agapiti et

Delighted.

(8 August): VI id. aug. Secundi, Carpophori, Victorini et Severiani in Albano; et

Ostense VII ballistaria, Cyriaci, Largi, Crescentiani, Memmiae, Julianae et Smaragdi.

(9 August): III id. aug. Laurenti in Tiburtina.

(13 August): id. aug. Ypoliti in Tiburtina and Pontiani in Calisti.

(August 22): XI Kal. sept. Timotei, Ostense.

(August 28): V Kal. sept. Hermetis in Bassillae, Salaria Vetere.

Septembre canteens (5 September): Non. Sept. Aconti in porto, et Nonni et Herculani et

Taurines.

(September 9): V id. sept. Gorgons in Labicana.

(September 11): III id. sept. Proti et Jacinti in Bassillae.

(September 14): XVIII Kal. oct. Cypriani Africae, Romae celebratur in Calisti.

(September 22): X Kal. oct. Bassillae, Salaria vetere, Diocletian IX and Maximiano VIII

cons. (304).

Canteens Octobre (14 October): prid. id. oct. Calisti in via Aurelia, milestone III.

Canteens November (9 November): V id. nov. Clementis, Semproniani, Claudi, Nicostrati

in committee.

(November 29): III Kal. dec. Saturnini in Trasonis.

Canteens December (13 December): id. dec. Ariston in Portum.

The Chronograph also contains a depositio episcoporum because each local Church kept the list of its bishops updated to attest to its apostolic filiation and therefore its legitimacy. The burial place was also indicated for the bishops so that the bishop in office could visit the tomb of his predecessor on the fixed date with a small delegation of clerics and faithful. Among the bishops, starting from the fourth century, people began to honor those who, despite not having been martyred, had shown themselves to be a witness to Christ, or "confessor". This term, originally synonymous with martyr, was applied in the third century to Christians imprisoned, sentenced to perpetual prison or tortured for their faith, who nevertheless managed to escape condemnation. Then between the fourth and sixth centuries it assumed the meaning of "white martyr", that is, one who had sacrificed his life to ascesis. Finally, with the Middle Ages it would have been replaced by the pagan saint which in Latin - sanctus - meant sacred, worthy of religious respect, accepted by the gods.

It was logical that even non-martyrs were venerated because with the Constantinian age the persecutions had waned, and the faithful had begun to honor other forms of evangelical witness, such as those of the desert fathers, ascetics, founders of monasticism, virgins or of the widows who had consecrated themselves to Christ, and finally of the shepherds who had best testified their faith. Thus, starting from the fifth century, martyrs and confessors were merged into a single list: the first martyrologists were born who, unlike calendars, whose function was to indicate the local glories of the various Churches, ordered all the names of the saints in the order of days. belonging to the universal Church that the author was able to know. The oldest surviving is the so-called Geronymian Martyrology, erroneously attributed to St. Jerome. The copy, which dates back to 592, was compiled in Auxerre, France, but the original, written in northern Italy and lost, probably dates back to around the middle of the 411th century. The Geronymian had obtained information from the aforementioned Philocalian chronograph, from a Syriac martyrology of 360 (inspired in turn by a Greek martyrology written in Nicomedia around XNUMX), from the Carthage calendar, also from the XNUMXth century; and other news the writer had drawn from the churches of northern Italy, Gaul, Spain and Brittany.

At the end of the sixth century, St. Gregory the Great knew of its existence because he wrote to Eulogius, patriarch of Alexandria: "Gathered in a single book, we have the names of almost all the martyrs, with their passions marked every day, and every day we celebrate masses in their honor. However, the form of their passion is not indicated in this volume. There is only the name, the place and the day of death " [3]. The English monk Bede the Venerable (who died in 735) remedied this gap, who at the beginning of the eighth century composed a martyrology less dense in names but with a short piece of information for each one, taken from the acta, the Passiones martyrum and subsequent legends. Thus the classical martyrologists were born, among which that of Usuardo of Saint-Germain (865) assumed greater authority, which would be read throughout the Middle Ages in canonical chapters and monasteries, and gradually enriched with other news. This text, collated with that of Bede and with another of Adonis of Vienna (860), was used for the preparation of the Roman martyrology wanted by Gregory XIII to put order in the great jumble of dates, often unfounded or in contradiction with each other. The first edition of the Roman Martyrology, which came out with an official letter from Gregory XIII in 1584, was not, however, perfect. Many other revised and corrected ones followed up to that of Benedict XIV in 1748 which served as the basis for subsequent reprints with the addition of the new saints.

If the cult of individual martyrs and saints dates back to the very first centuries, starting from the end of the fourth century there was a need in the East to celebrate all the saints, known or unknown, in a single feast: the Syriac Church during Easter time. , the Byzantine on the Sunday following Pentecost. In Rome, the birth of what would later become the feast of All Saints dates back to May 13, 610, when Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon to the Virgin Mary and all the martyrs (Sancta Maria ad martyres). Subsequently an attempt was made to introduce in the city also the Byzantine festival which fell on the Sunday following Pentecost; but the new date did not last long because an ancient tradition imposed on the Romans the solemn fast of the Tempora which ended with the Sunday vigil. With the Middle Ages, the Frankish feast of November 1, established in the XNUMXth century, as we have said, gradually extended from the Frankish kingdom to other countries until Pope Sixtus IV made it mandatory for the whole Western Church.

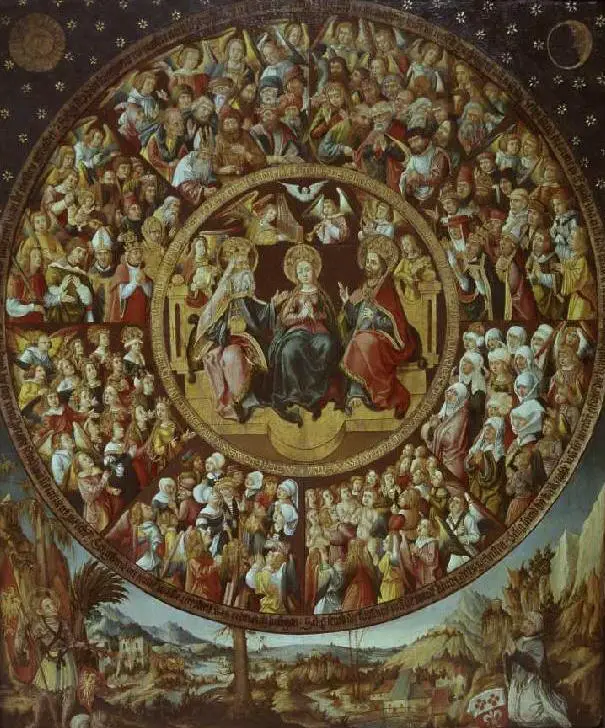

All Saints' Day is considered a solemnity in the new liturgical calendar, that is, it is part of the most important feasts because according to the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium of Vatican II "on the anniversary of the saints the Church proclaims the paschal mystery realized in the saints who have suffered with Christ and are glorified ». They are those who having assimilated the "model" Christ, having offered their own life with the "red" martyrdom (the real martyrs) or with the "white" (the ascetics), participate ontologically in the divine nature: through the narrow door of the "great tribulation", as John writes, they have reached the joy of communion, introduced to the inexpressible and ineffable presence of God. They contemplate him in his mystery of love as Father, Son and Holy Spirit [4]. "All stood before the throne and the Lamb," it is written in the Apocalypse, "wrapped in white garments, and carried palms in their hands": symbols of resurrection, of victory over evil and of glory. Sons of God in the Son become channels of grace in the mystical body of the Redeemer where all are happy when a member is in joy and suffer when he suffers; and therefore, not being able to remain insensitive to the spiritual needs of the brothers, they intercede with the Lord so that the requested grace may be granted. However, as the conciliar constitution Lumen gentium affirms with regard to the Saint par excellence, the Virgin rescuer and mediator, recourse to them "must be understood in such a way that nothing detracts or adds to the dignity and efficacy of Christ, the only mediator" [5].

November 1, which celebrates the death of all the saints as the day of their "birth", of their victory, of their assumption into divine communion, Christianized the Celtic New Year by not contradicting its spirit because, if we compare the holy to the grains of wheat, which descended into the earth in the autumn season to be reborn as plants in spring, we can better understand the words that Christ said to Andrew and Philip: "Truly, verily I say to you: if the grain of wheat fell into earth, does not die, remains alone; if it dies, it produces much fruit. Whoever loves his life loses it and whoever hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life. If anyone wants to serve me he will follow me, and where I am there will also be my servant. If anyone serves me, the Father will honor him " [6].

The Memorial of all the faithful departed

The following day, November 2, the Church commemorates all the dead according to a universal custom that is found in every tradition and has never had, except in the modern West, a sad and funereal character. There is, however, a European country where the commemoration resembles a family celebration during which the dead seem to mingle with the living. 'In Ireland,' wrote Yeats, 'the world of the dead is not so far from that of the living. They are sometimes so close that the things of the world seem only shadows of the afterlife. " For this reason the place where the Irish clans gathered was an old cemetery still in use or out of service, where justice was administered.

Even today in the nights of All Saints and the Dead, the Irish cemeteries are a sea of lights, as if to continue the Celtic tradition of Samuin when the tombs were opened and the dead mingled with the living: the feeling of closeness was such that every living thing - it was said - he could descend with them into the underworld on the sole condition of remaining there until the next Samuin. In those cold autumn days, the Celts brought profusion of flowers to cemeteries - perhaps dried, perhaps cultivated in greenhouses - to allude to the afterlife as paradise. They also used to pile up skulls because it was thought that the dead one belonged, for a time, to both kingdoms: however much, no one could tell. «Which allowed him, and in particular allowed his skull» explains Margarethe Riemschneider «to prophesy for the benefit of those who remained alive. He could also, if revered, radiate certain heavenly energies upon them ... The ossuary with its stacked skulls is more than a form of burial. The proximity of the skulls - which are not necessarily of known ancestors - is such, as Yeats says, that their shadow from beyond falls on the living. " [7] Houses of bones have been found in Brittany, Bohemia and Carinthia, all Celtic countries in antiquity.

During the wake, the skulls kept in the ossuary were painted and the night was spent drinking, playing and singing in the company of the dead. A faded echo of those vigils can be found today on Hallow'en night in Ireland and the United States, during which boys disguise themselves as skeletons or ghosts miming the return of the dead to earth, and walk from house to house asking for little ones. tribute and threatening if they do not get them to play some tricks which consists of smearing the windows with soap or smearing the shop windows. In a different cultural area in Mexico, the Todos los Santos festivals, which also include the Day of the Dead, reflect Aztec traditions not unlike Celtic ones. The cemeteries look like a flowery meadow in spring, there is no sadness but joy in the re-enactment of relatives and friends. For the festival, bread cakes are made in the form of skulls and skeletons to signify that life is reborn from the dead, from the "buried seeds", or that the dead "feed us".

On the other hand, even in our country they still eat the "bones of the dead" on November 2: this is the name in Sicily of those almond sweets that the pastry shops sell from the eve until the end of November 2. But the custom is not limited to Sicily: in various other regions, from Sardinia to Umbria, sweets of the dead are sold for the occasion. That the dead bring life is therefore also an Italian belief: on the other hand, in Sicily itself it is said that the dead, on the night consecrated to them, bring gifts to children, such as the Befana; mothers tell their children that the dead leave their homes in those magical hours and come down in droves to the homes of the living bringing them little gifts. Even the Etruscans believed that the dead sat next to them on the edge of the tombs participating in the funeral meal: in the necropolises, dead and alive were always in the presence of each other, as if there was no boundary between the two worlds for a specific time.

If the Celts celebrated the dead on November 1st, the ancient Romans dedicated nine days of February to them, during the transition from winter to spring, from the old to the new year; and even when the Kalends of January were established as the only new year, the ancestors continued to be honored during the Parentalia which lasted from 13 to 21 February. The ceremonies consisted of the parentatio tumulorum, which indicated a funeral service given to the tombs. Wreaths of flowers, scattered violets, spelled flour with a grain of salt, bread soaked in wine were offered on the family tomb: parva petunt Manes, the Mani are content with little, wrote Ovid. The culminating and final day of the Parentalia were the Feralia (February 21) who in ancient times fell in the last quarter of the moon. According to Varrone "Feralia derives from the underworld, dead, and iron, to bring, because on that day the funereal foods were brought to the family tomb from those who had the right to do so" [8]. Festus, on the other hand, derived the name from ferio, meaning "to wound" the victims; but this interpretation does not seem justified by any sacrifice remembered on that day [9]. The parentes were also remembered individually in their dies natalis, or birthday. Family members gathered around the tomb of the deceased to offer libations or present food to his manes and to participate in the refrigerium, the funeral banquet.

Christians also began to honor their dead who buried in the necropolises built along the consular roads: each dead man had a niche dug into the tuff, where in the recurrence not of birth but of death, which as explained was the true dies natalis, he was offered a mass. At the time of St. Ignatius of Antioch and St. Polycarp, in the second half of the first century, the custom was now widespread. The Church, however, wanted to curb what it considered abuses and established that the mass was celebrated only on the sepulchers of the martyrs; later, in the XNUMXth century, it also prohibited funeral banquets, perhaps to distinguish Christian from pagan commemoration. But some customs survived for a long time: Prudentius, who lived between the fourth and fifth centuries, remembers the violets and flowers that were scattered on the tombs, like the libations on the tombs of loved ones. Sometimes, through holes made on the lids of the sarcophagi, milk and honey or precious ointments were dripped directly onto the body. Then with the raids of the barbarians, the catacombs, which were located outside the Aurelian walls, became unsafe and the dead began to be buried inside the cities, in the churches and along the nartecuses.

The Commemoration of all the dead was born later, in the heart of the Middle Ages, in imitation of the Byzantines who celebrated an Office in suffrage for all the dead on the Saturday before the Sunday of Sessagesima, or the octave before Easter, in the period between the end of January and that of February: it was the Benedictine monasteries that introduced this practice into the Latin Church during the 998th century. A few decades later, in 1, St Odo of Cluny ordered the monasteries dependent on the French abbey to ring the bells with the traditional funeral tolls after the solemn vespers of November XNUMXst, announcing to the monks that they were to celebrate the Office of the dead in choir. The following day all the priests would offer the Lord the Eucharist "pro requie omnium defunctorum": evident concern to Christianize the Celtic ceremonies that probably still survived in rural areas not fully evangelized.

The rite gradually spread in diocesan rituals and in those of other religious orders until the fourteenth century before Rome accepted it: the Anniversarium omnium animarum - as it was called appears for the first time on November 2 in the Ordo romanus of XIV century. On that day the consistory was not celebrated nor was it preached during mass. Which had and has the function of praying for mercy for the dead, underlining the communion of saints that unites the praying and militant Church to the one suffering and expiant in purgatory: mystical body where the blessed of heaven, the "travelers" of the earth and souls in purgatory.

Today, after mass, people go to the cemeteries to adorn the tombs with flowers, especially chrysanthemums (symbols in the East, where they came from, of sunshine and therefore of immortality), and to remember the missing relatives with the whole family. But unlike the ancients, we live this day under the banner of sadness and we consider cemeteries as gloomy places, not to be frequented except on sadly necessary occasions. Instead, the cemetery should go back to being familiar and smiling places because they contain our roots, all those who preceded us, transmitting us not only life but also the heritage of traditions, culture and moral rules on which our community is founded. For this reason, the Commemoration of the dead is not just a religious celebration or an occasion to commemorate our dead, but a real feast of the city. And rightly in 1987 the Municipality of Turin invited citizens to adorn all the graves with flowers, which the administration made available for free, and sent the Banda dei Vili Urbani to the cemeteries so that with its joyful notes it would also underline the value Civil War of the Memorial. Finally, to encourage the Turinese to walk in the cemetery outside the recurrence, he distributed a free guide to the monumental cemetery, significantly entitled Our roots: thus a new custom was born that should be extended to all Italian cities.

Note:

[1] See Revelation 1, 5 and 2, 13.

[2] Epistule 12.

[3] Epistle 8, 29.

[4] In this regard, see also Giovanni Marchesi, The Gospel of Hope, comments on the festive lectionary, year B, Rome 1987, p. 514.

[5] Lumen gentium 62.

[6] John 12, 24-26.

[7] Margarethe Riemschneider, Living with the dead, in «Religious knowledge», n. 1, 1981, p. 69.

[8] From the Latin language VI 34.

[9] Festus, Feralia.

2 comments on “Alfredo Cattabiani: "The feast of All Saints and the Celtic New Year""