The purpose of this study is to introduce the complex and controversial topic of the history of the indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic in the Tsarist Empire and in the Soviet Union. After a brief introduction to the ethnic and cultural geography of the region, the policies adopted over time towards the aforementioned populations of the Siberian Arctic, the issues of nationality, protection of minorities and their role in the cultural framework of the Tsarist Empire and of the 'USSR.

di Simone Savasta

the quotes in the photo captions are taken from Russian ethnological and ethnographic shops of the XNUMXth - XNUMXth centuries [via sachaja livejournal]

The purpose of this study is to introduce the complex and controversial topic of history of the indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic in the Tsarist Empire and in the Soviet Union. After a brief introduction to the ethnic and cultural geography of the region, the policies adopted over time towards the aforementioned populations of the Siberian Arctic, the issues of nationality, protection of minorities and their role in the cultural framework of the Tsarist Empire and of the 'USSR. Subsequently, Lenin's and Stalin's gradual approach will be analyzed in more detail: in both cases, the goal was to push these populations to get out of the state of backwardness in which they found themselves in order to "engage" in the economic and cultural development of Russia: a "destructive" approach that aimed to eradicate these populations from their ancestral lifestyles, imposing an artificial ideology from above that found little space in the cultural conceptions and traditional lifestyles of these populations.

1. GEOGRAPHICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE RUSSIAN ARCTIC

Rossiysky Sever, the north of Russia, extends for a distance of 6000 km from the Finnish and Norwegian borders through the Urals and Siberia to the Bering Strait and the Pacific Ocean. It covers large areas of taiga (boreal forests), tundra (treeless swamps and pastures) e polar deserts. The north-south extension of this belt extends from about 1000 km in Europe to about 3000 km in central Siberia and the Russian Far East. In this land they live about 20 million people, concentrated mainly in cities and settlements along rivers and industrial centers. Only about 180.000 of them belong to about 30 small Aboriginal groups - the indigenous peoples of the north. Most live in small villages near their subsistence areas, where they carry out traditional occupations such as reindeer herding, hunting and fishing. But the reality these people face today is far from an idyllic carryover from the past. Since the colonization of the North, vast expanses have gradually been converted into areas for alien settlement, transport routes, industry, forestry, mining and oil production, and have been ravaged by pollution, irresponsibly managed oil and mineral exploration and from military activity.

In tandem with the environmental disaster went the social decay of indigenous societies since the beginning of the Soviet era, with the collectivization of subsistence activities, forced displacements, spiritual oppression and the destruction of traditional social models and values. The result was the well-known minority syndrome characterized by loss of ethnic identity, unemployment, alcoholism, disease, etc. of most of the supply and transportation system in the remote areas of the North. Having been incorporated into the alien Soviet economic system, made dependent on modern infrastructure and product distribution, people now find themselves left alone with no supplies, medical care, increased mortality, financial means and sufficient legal expertise to deal with the situation. The desperate road back to the old ways of living has tempted many, but is often hampered by the degradation or destruction of the natural environment. Against this horrendous backdrop, the cultural survival of these small ethnic groups may seem nearly impossible. But they fight tenaciously, showing incredible resistance, and their case has already gained ground in many national and international forums.

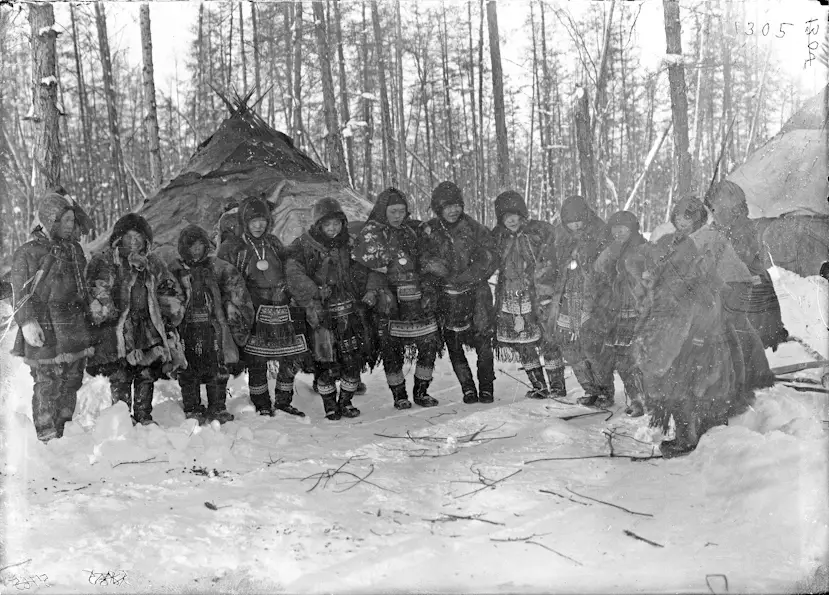

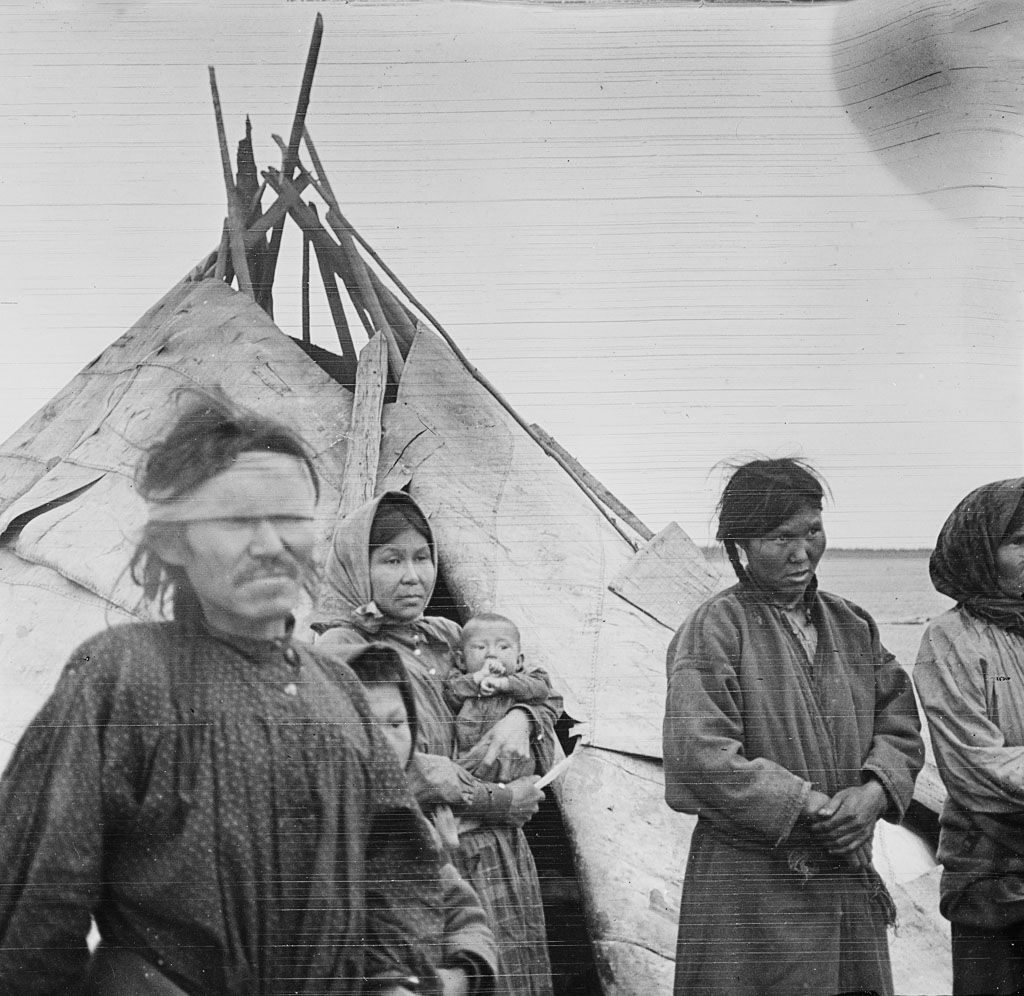

Chukchi residing in Anadyr, 1906

As everywhere on earth, the Russian north was subject to migrations of peoples in the course of human history. Up to approx. 2000 years ago, the North was dominated by ancient Siberian tribes whose cultural relationships are poorly understood. The pressure of the extension of the southern adjacent populations gradually pushed these tribes north, as they mingled - and were partly assimilated - with the newcomers. [1]. A group of descendants of these ancient Siberian tribes is made up of the Yupik (Eastern Eskimo branch) and give them Aleuts, who migrated mainly to Alaska and form a common cultural group with other North American peoples. In Russia, fewer than 2000 Yupiks live in the villages of the Bering Strait and about 700 Aleuts on the islands of Komandorsk and Kamchatka. The largest of the Proto-Siberian language groups is the paleo-Asian group, represented by Chukchi, Koryaks and Itelmens. Upon the arrival of the Russians, these peoples inhabited most of Chukotka, Kamchatka and the areas around the North Sea of Okhotsk. Today they are concentrated in the autonomous areas of Chukotkan and Koryak in the far north-east. With a population of 15.000 (Chukchi) and 9000 (Koryaks) these peoples belong to the largest ethnic groups.

The Itelmen (2500) were once also widespread throughout Kamchatka. They are now confined to a small strip of land on the southwestern coast. Much of their former population is mixed with Russian immigrants, who speak the Russian language but have developed a distinctive local culture. These people are called Kamchadal and claim the official status of indigenous people which they lost in 1927. Their number is around 9000. Yukagir, another Proto-Siberian group, once inhabited large parts of northeastern Siberia between the Lena mouth and the Bering Strait. The remaining 1000 people are mainly confined to the Kolyma area in northeastern Yakutia. THE Chuvans (1300) in the upper part of the Anadyr River are originally a Yukagir tribe that adopted the Chukchi language and assimilated partly to Chukchi and partly to Russian culture. Isolated linguistic remains of an ancient Siberian population are also represented by Nivkhi (4600) at the mouth of the Amur and on northern Sakhalin, and come on kets (1100) of the middle valley of the Yenisey river.

Central and Eastern Siberia has experienced extensive immigration of Tungus and Turkic tribes in several impulses from the south, since 550 AD They spoke Altaian languages. The Turkish Uyghurs, the first invaders, were subsequently assimilated to the peoples Tungus which appeared after 1000 AD and mixed with the native Yukagir, Koryak and the people of the Amur River. Relatively large groups of Evenks (30.000) and evens (17.000), widespread in central and eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East, as well as a number of smaller groups in the Amur district and on Sakhalin (Nanais, Udege, Orochi, Ulchi and Negidals) are the descendants of the penetration of the Tungus, which however also show more ancient cultural elements. The Yakuts Turks did not arrive in present-day Yakutia until about 1500 AD. They diluted the Yukagir, Even and Evenk populations. Having a large number, 380.000, and being the titular nation with nearly 40% of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), the Yakuts are not considered "indigenous". A subgroup of the Northern Yakuts, reindeer herding, however, does not differ much culturally from the indigenous minorities of the area. A fairly new ethnic group, i Dolgan (7000), developed in the following centuries mainly from Evenk, but also Yakut, various Samoyed and Russian elements in southern Taymyr. They speak a Yakut dialect.

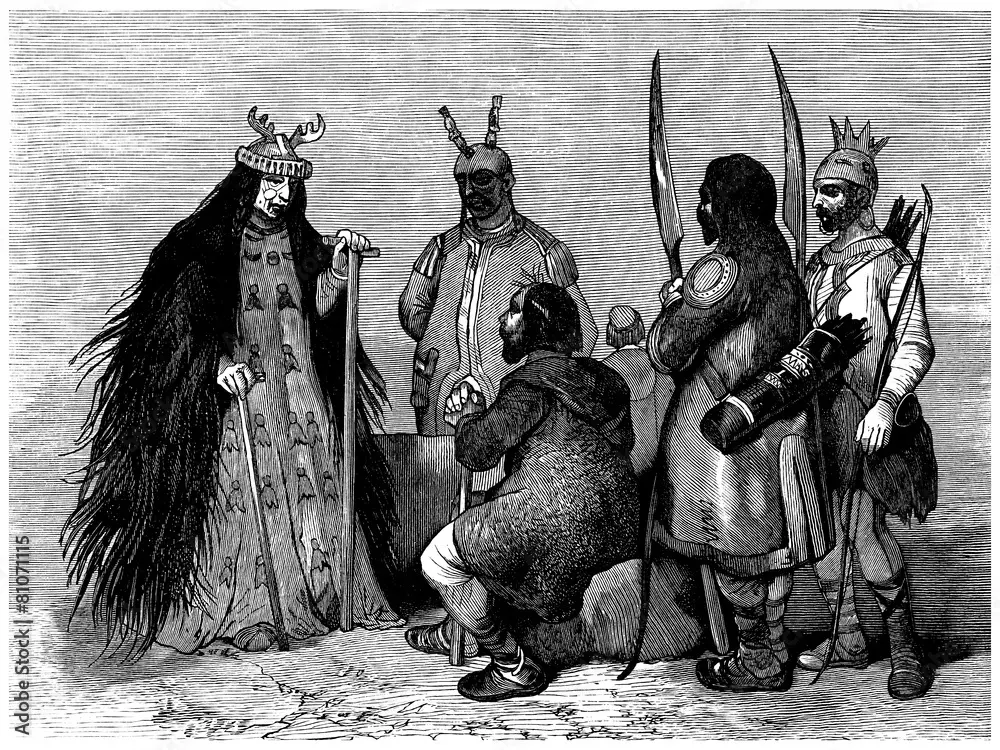

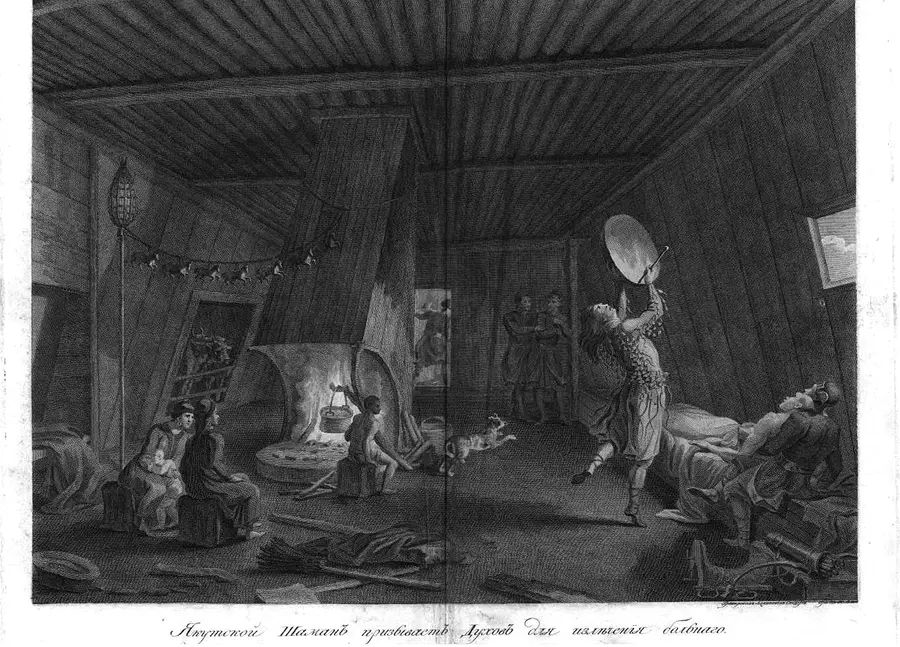

Tungusians, lithograph from the end of the 800th century

Western Siberia and northern Europe were gradually penetrated by the tribes of the Ural language branch, starting several thousand years ago. Linguistically, they are divided into a Finno-Ugric sub-branch and a Samoyedic sub-branch. The Finno-Ugric branch includes the Finnish subgroup to which i sami in Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula and the komi west of the Urals. While only around 1800 Saami live in the Russian part of their home area, the Komi (340.000) have a similar, non-indigenous status as described above for the Yakuts. Ugric languages are spoken by the Khant (22.000) and from mansi (8000) in the Ob River Basin and in the Yamal area east of the Urals. THE Samoyed groups probably have their origin in the Sayan area in southwestern Siberia, from where they gradually migrated to their current areas of residence ca. 2000 years ago. They include i articles (34.000, the largest indigenous group) along the Arctic coast from the Kanin Peninsula to the mouth of the Yenisey, the Nganasan (1200) on northern Taymyr and the dishes (200) and i Selkup (3600) in the Yenisey River Basin.

Samoeds

2. SOCIETY AND LIFESTYLE

Despite the different historical, ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, the peoples of the North had to adopt quite similar subsistence cultures when they arrived in the subarctic and arctic regions. However, distinct differences have developed between endemic fauna and climatic zones, sometimes within the same ethnic unit. The exchange of products between these cultural groups has been important throughout history. Due to collectivization and forced relocation during the Soviet era, many of these differences have now vanished. Coastal cultures developed among peoples living in areas with important marine mammals (walruses, whales, seals), particularly in the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Okhotsk or the Bering Strait (Aleuts, Yupik, coastal Chukchi). Among other Far Eastern groups, the marine hunting it is part of the annual cycle, while their main occupation is inland fishing (salmon), hunting or reindeer husbandry. River cultures occur mostly in the Far East. Typical fishing peoples are the Nanai, Ulchi and Udege in the Primorye area of the Far East, but also the Kets in the center of the Yenisey River. Cultures of the tundra and taiga are present throughout the north of Russia. The basic traditional occupations are reindeer breeding, hunting and trapping, freshwater fishing and gathering.

These peoples are traditionally nomadi or semi-nomads. Since collectivization took place during the Soviet era, most reindeer hunters and herders live in settlements throughout the year, although many continue to migrate seasonally with the herds. Reindeer farming is the basic subsistence occupation of many northern peoples. It is not necessarily the most typical indigenous occupation, but the most characteristic one that still has economic significance. Moreover, it is not just an economic occupation, but it has developed into one lifestyle closely connected with ethnic identity. There are large-scale herding cultures such as those of the Nenets, Khants, Chukchi, and Koryak, and small-scale farming mainly for draft and saddle animals as a subsidiary occupation for many people of the taiga. Reindeer farming, however, is very sensitive to environmental changes [2]. Modern development has created a serious threat to reindeer farming and related cultures. The hunting of fur animals for uses other than domestic ones, and later the development of fur farms, was initiated by Russian colonizers for most of the ethnic groups. The Tsarist governors demanded furs for it forbidden (a colonial tax). Furthermore, commercial interests in the fur trade developed as a means of receiving commercial goods from the Russians.

Koryaki

The indigenous peoples of the north are traditionally animists. They believe that the sky, the earth and the water are populated by various spirits that influence the life of humans. They produce images of these spirits in human or animal form, which play an important role in their rituals. THE sacrifices to guardian spirits in the form of animals and other food items were common in the past. An essential common cultural trait is traditional religion, which, prior to Russian colonization, consisted exclusively of forms of shamanic animism, the belief in an animated nature, that is, in the existence of spiritual entities in every natural object and force. Religious practices were carried out by shamans who were mediators between people and the spirits of other worlds. Through contact with spirits, the shaman healed diseases, predicted the future and delivered the souls of the deceased to the world of the dead. Man can get in touch with these beings and they with him.

- Shamans, after a period of training, they can visit nature spirits in a state of trance, so that their soul temporarily leaves the body and travels to another plane of reality, generally off-limits to the common man. This trance is evoked through the sound of drums and monotonous chants, and only in exceptional cases - as far as we know - through drugs. The shaman makes these trips to get in touch with spirits in order to cure diseases or other inconveniences, mostly offering sacrifices. These journeys can be dangerous for shamans; it is not rare that the soul has not returned to the body and that the shaman is dead. Many times, however, the journey is successful: the discomforts are eliminated and the sick heal quickly. The application of natural medicine and its various treatments obviously plays an important role in this.

An important plane of reality which must be known by the shaman is that of the spirits guide. Among these beings, often in animal form, the shaman chooses his allies, so that they assist him during his dangerous journeys in the world of the deceased or even in the world of creative spirits. The retribution for these spirit guides always consists of sacrifices. The conception of the world of shamanic animism of the Siberian peoples is similar to that of the American Indians and other indigenous peoples, based on the idea of an essential balance in nature: everything that happens has consequences and repercussions on everything. However, this conception is limited to the connection of cause and effect at the level of the intellectually conceivable world [3]. Although many of the natives officially converted to the Russian Orthodox Church before the October Revolution, Christianity has never had a profound impact on the religious beliefs of groups as a whole.

As we have seen, under the definition "peoples of the North" there are great linguistic and historical differences. However, there are a large number of cultural similarities, largely due to the environmental pressures of the Arctic and Subarctic territory, which force them to develop very similar economies. It is climatic and geographical needs, rather than ethnic origin, that determine economic activities. Fishing, sea and fresh water, hunting and reindeer husbandry are, to varying degrees, the traditional economic sectors of most of the indigenous peoples of the north. From the meeting with the Russian settlers came the breeding of fur animals. Agriculture is practiced only south of the permafrost limit, by the Kareli and by part of the Cantos and the Jakuts. In the southern territories of Yakut and Evenki, cattle and horse breeding is extremely widespread. The methods of carrying out economic activities, the use of traditional tools, crafts and new artistic forms such as painting and literature differ naturally from people to people and from area to area.

3. THE CzARIST EMPIRE E

THE INDIGENOUS QUESTION

Indigenous peoples around the world have experienced the colonialism, assimilation and paternalism, in both capitalist and socialist systems. The conquest by the white man of the Russian north, Siberia and the Far East does not differ much from known atrocities from other parts of the world. The Russian pluri-national empire was formed through an expansion that lasted many centuries. It is characterized by a great ethnic, confessional, social and cultural variety. The rights of minorities have always been unequally respected [4]. Within the great Russian empire, however, many of these cultures have failed to survive to this day. Tsarist loyalty was the main condition for a non-confrontational relationship with Moscow.

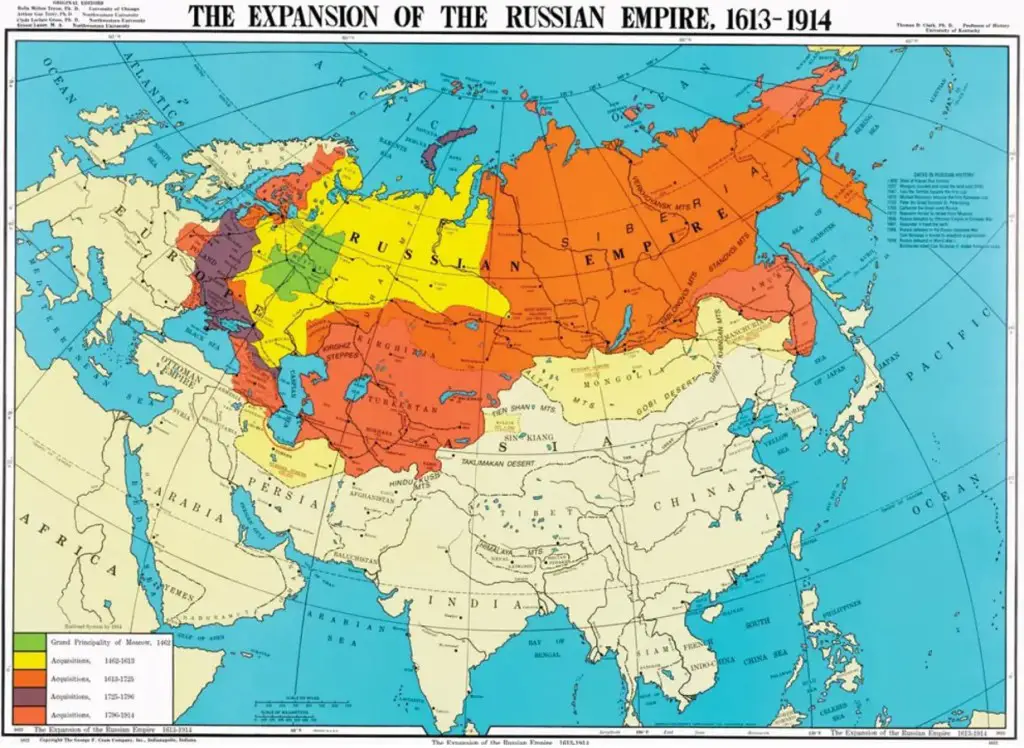

The north of Russia and Siberia is traditionally inhabited by indigenous peoples who had been masters of these lands until the arrival of the Russian conquerors. The Russians define these ethnic groups, which often number fewer than 2.000 people, peoples of the North. According to the history texts, the Russians, in their expansion towards the east and north, found an almost deserted country. Russia's advance towards the "Far east", The wild East, recalls the expansion first in Europe and then in the United States in the"Far West"North American [5]. In both cases the colonizers came to profoundly subvert the social and political order of the indigenous peoples. Depending on the climatic conditions, lake and marine fishing, hunting, reindeer herding and agriculture south of the permafrost border were the main subsistence base of the indigenous peoples.

Before the Russian colonization, as has been said, the indigenous peoples largely professed a shamanic animism. Shamanism is a cultural and religious element common to all indigenous peoples. From 1000 to 1300 in the northwestern part of the Slavic territory, around the city of Novgorod, an area inhabited by Finnish stocks was formed. Among these ethnic groups were the Kareli, the Vows, the Isciori and the Vepsi in the Northwest, the Finna-speaking Sami (Lapps) in the far north, the Sirjeni (today Komi), Permjaki, Ostjaki, Voguli (today Mansi) and Samojedi in the North East. All these peoples were subject to the administration of the Novgorod city republic. The Russians, at first, pursued a policy of peaceful acculturation trying to integrate these ethnic groups into Orthodox Christianity. Despite the vigorous policy of acculturation, some of these peoples (eg the Kareli, the Komi) have been able to preserve their ethnocultural identity up to the present day.

The annexation of the republic by Tsar Ivan III in 1478 definitively conferred the character of a multi-ethnic nation on the Grand Duchy of Moscow. After the military conquest of the khanates of Kasan and Astrakhan (1556), Russian expansionism towards the West was held back at the end of the century by the Livonian War. But the transural East remained open, where the Khan of Sibir reigned in the region of upper Ob. In the 500s and 600s Siberia was populated by many small ethnic groups, organized mainly in the form of tribes. In the taiga further north, however, lived the Manchur Tungus and the Jukaghiri who lived by hunting and fishing. The Samojedi, the Ciukci, the Kamciadali / Korjaki were instead nomadic reindeer herders who lived in the tundra. In the south around Lake Baikal the Mongolian-speaking Burjatis, the Turkmen Teleuts and Yakuts, and finally the Sciori, also nomadic shepherds and cattle breeders, had settled. The only farmers in this huge area were the Tartars, concentrated in the areas on the edge of the steppe and the Ostjaki (Voguli) of Ugrian language.

Politically, all these ethnic groups were poorly organized. The West Siberian khanate it was the only empire of any significance. For decades, most of these ethnic groups resisted the Russian advance rather tenaciously. Already at the beginning of the eighteenth century there were large ones rebellions. The historical sources of this period are scarce and prevent an exact reconstruction of the events. The continuous rebellions of the eighteenth century forced Moscow to a harsh repression in order to maintain its power. Draconian measures were applied that came to real extermination campaigns, as in the case of the Chukchi. The increasingly compact opposition of non-Russian ethnic groups forced Moscow to modify its integration policy, making it more pragmatic, cautious and tolerant. Moscow encouraged the training of local elites by confirming the privileges of the chieftains and delegating to them minor administrative tasks and the collection of the forbidden, the tributes that were paid in the form of furs [6]. For the rest, Russia opted for non-interference in the internal affairs of individual ethnic groups. The forbidden it consisted mainly of furs. The often very high tax requirements have changed the employment patterns of many ethnic groups and endangered their livelihoods.

The Tsar's order stipulated that indigenous peoples should be treated with respect and hospitality, while military actions would only be necessary in the event of armed uprisings. But local governors and tax agents had their own laws and often did not comply with central government directives at all: historians report continuous looting and violent invasions that have led to the extermination of entire nations. A usual procedure for charging him forbidden to indigenous peoples it was taking hostages, often respected elders. It was also customary to kidnap, or buy and enslave women and children. Tax raids often degenerated into looting, sometimes with raids and murders. Many times, the entire subsistence base of a local indigenous group has been destroyed and people have died of cold or starvation. In some places, the oppression continued until the 19th century. Towards the end of the XNUMXth century, most of Siberia as far as the Pacific coast was under Russian control.

As Russian economies deteriorated, politicians decided to subdue the last peoples who resisted and opposed, the Chukchi and Yukagir, by force. The Yukagir were reduced to about half their population. During smallpox epidemics of the XNUMXth century and subsequent disasters, another 80% of the remaining population disappeared. However, official Russian policy towards indigenous peoples in the 19th century was not always negative. Considerations of humanity and concern for the exploited indigenous people led to attempts to control the situation by means of various (rather ineffective) laws banning slavery, limiting the collection of taxes, banning the sale of liquor and, again in 1912, banning Russian traders to enter certain native territories. However, the main development trend continued: loss of land, economic decline, dissolution of subsistence models, disintegration of the social framework.

The peoples were also granted a wide religious freedom. Peoples such as the Samojedi, Chukchi, Chuvash and Ceremissi were allowed to continue practicing shamanism. Siberian voivods, Moscow-appointed local governors, were often urged by the Tsarist government to be tolerant of the tribes and avoid levying forbidden by force. But local authorities, traders and settlers did not heed these exhortations: corruption, blackmail, slavery and violence reigned in many areas. In 1600, to guarantee the supply of the occupying troops, Russia had settled numerous peasant-settlers in Siberia [7]. Despite this policy of settling in the more isolated territories of the tundra and taiga, the indigenous peoples managed to preserve their tribal structures. For a long time Russia treated nomads as Serie B citizens. In 1767 they could not yet participate in the assemblies of the Legislative Commission.

At the beginning of the 800th century, some reformers, including the governor general of Siberia MM Speranskij (1772-1833), tried to "bring backward ethnic groups to a higher level of civilization": the so-called inorodcy (foreigners) finally obtained their own legal status. The statute of 1822 gave them extensive administrative powers. Through the "law for the administration of the indigenous population" the state tried to protect them from the bullying of the Russian colonists and from exploitation. But this reform program, inspired by the Enlightenment approach and in the wake of the pragmatic tradition of Russian minority policy, could only be partially implemented. Corrupt employees, who managed to escape the controls, prevented the affirmation of the state of inorodcy. The natives remained second-class citizens, in spite of privileges and provisions. The policy of Nicholas I (1825-1855) aimed at preserving the status quo. Each change proved dangerous because modernization provoked frequent rebellions among the local peoples.

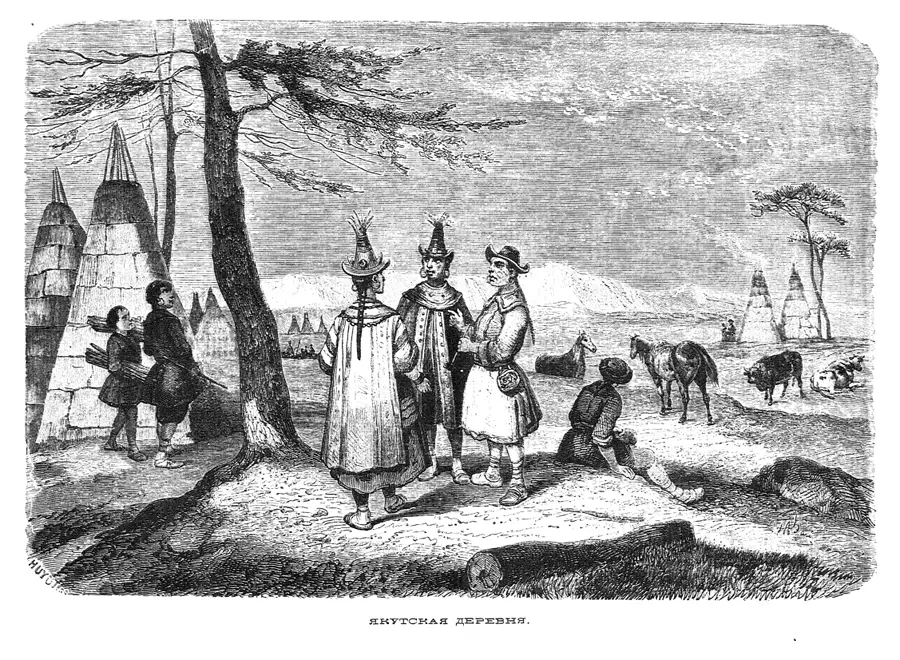

Yakut, late XNUMXth century lithograph

Starting in the mid-800th century, a policy of integration was again reverted and it was strengthened scientific study of the various ethnic groups [8]. Some linguists created Cyrillic alphabets for peoples without writing such as the Chuvash, Votjaki and Yakuts. Vocabularies, grammars and school texts were developed; a teaching institute for the training of non-Russian teachers was also founded. However, the primary objective remained that of spreading the Orthodox faith. But towards the end of the 800th century these initiatives were harshly criticized by Russian nationalists. Ultimately, however, this policy had results, since there was no significant rebellion by a non-Russian people between 1864 and 1905.

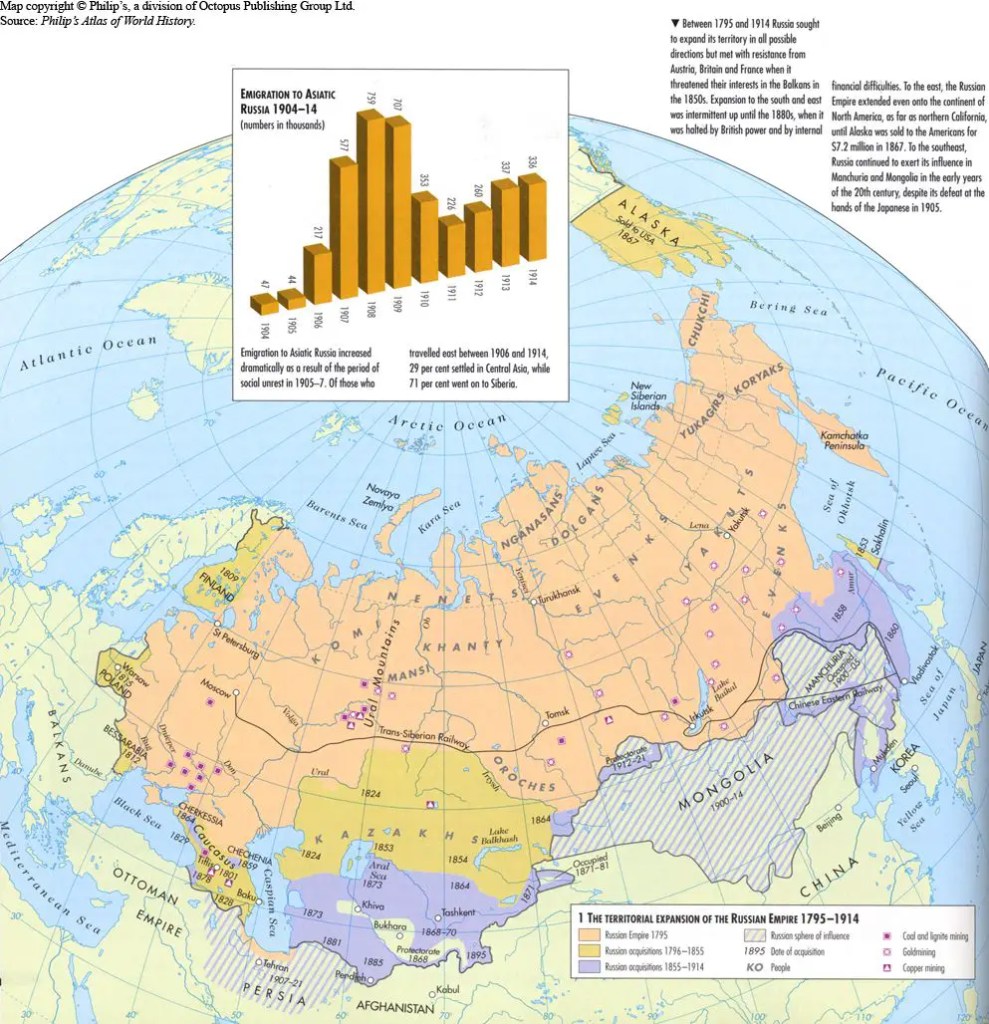

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Siberia became a privileged destination for Russian colonists [9]. These at first favored western Siberia, but after construction of the Trans-Siberian railway they also began to settle in eastern Siberia. For many peoples, colonization meant an extension of their living space (Nenzi, Ciukci, Evenki, Eveni), but for others a drastic reduction (Enzi, Jukaghiri, Korjaki, Itelmeni). In the course of an extensive policy of relocation and forced migration promoted by the Stolypin land reform, over three million Russian peasants had been settled by 1914. Often the hunting and fishing practiced by local populations had to give way to the breeding of fur animals, which had a higher commercial potential.

4. THE SOVIET UNION E

THE INDIGENOUS QUESTION

Soviet policies towards the Siberian indigenous peoples were strongly influenced by the Marxist doctrine. During the post-revolutionary civil war which lasted from 1917 to 1924 (locally in the Far East), the Soviet administration replaced the Tsarist system of government. Passive victims of the war between the two Russian factions, the indigenous population slipped into a dispute between two competing policies: a Leninist line, aimed at guaranteeing development according to its own cultural premises, while the other - the Stalinist line - aimed at the complete elimination of ethnic differences and the integration of all national groups into a common Soviet society.

The majority of non-Russian ethnic groups did not participate in the Revolution. However, various non-Russian peoples of the periphery contributed to the destabilization of the political order. Moreover, the Revolution also stimulated the national redemption of many peoples. Their intellectuals stirred up cultural, social and political demands [10]. In 1905 the Ciuvasci managed to publish a weekly in their mother tongue. But the attempt of the Yakutis to organize themselves on a political level was soon stifled. The "Declaration for the peoples of Russia", approved immediately after the Revolution, was never applied. In the following years, within the "Committee of support for the peoples of the North" (Northern Committee) there were bitter discussions between those who wanted to grant indigenous peoples the right to their own cultural development and among those who opted to integrate them into the working class . In the end, the latter won.

Tungusians

When Russia was divided in the new administrative order, some territories with indigenous populations also obtained a certain autonomy. The lands of the Yakuti (1922), the Kareli (1923) and the Komi (1936) were recognized as status of autonomous republic. However, according to the laws in force, the leaders of the individual tribes (shamans, reindeer owners) did not have access to the upper ranks of the local Soviets and Congress. However, the Russians initiated some reforms to revive the economy of the Northern territories. An attempt was made to develop written languages to combat illiteracy, which was still widespread.

Lenin's policy of minorities tied in with the nationality policy of pre-modern Russia. To keep their power, it was decided to give more space to minorities. After the Bolshevik revolution, many exiles became ethnographers and, after vigorous pressure, managed to form, in 1924, the Committee for Assistance to the Peoples of the Northern Borderlands.. Conceived as the Soviet equivalent of the US Indian Affairs Office, the Committee assumed that circumpolar peoples, or "small peoples of the North", were increasingly called upon to distinguish them from administrative and political autonomy. 'assertive Iakut, Buriat and Komi (Zyrian) - they were in a phase of "Primitive communism": there was no class stratification between them and whatever exploiter there was, he was Russian. Consequently, the task of the officials / ethnographers of the north was to protect their "little people" from various external "predators" and to assist them, with great caution, in their climb to evolution.

Yakut

Lenin began a severe campaign of territorial definition of autonomy: he wanted to create ethno-territorial autonomies. Lenin and Stalin defended nationalism and ethno-territorial self-determination to restore the confidence these peoples had lost in the Russian oppressive state: to develop local language and culture to be able to take part more quickly in the universal culture of revolution and communism. However, many opposed it: in 1918 Latsis attacked "the absurdity of federalism". In 1919 Bukjarin and Pyatakov opposed national self-determination. However, Lenin also won their votes because, according to Tomsky, no one wanted national self-determination but everyone considered it "a necessary evil" [11]. The NEP constituted a temporary but deliberate reconciliation with "backwardness": peasants, traders, women, all non-Russians, particularly the various "primitive tribes". Postponed their abolition, the aim was to build the nation. In any case, Lenin believed that internationalism consisted not only in the formal equality of nations, but also in an inequality at the expense of the oppressor. He had to give more space and concessions to the "offended" nationalities.

A study of the ethnic composition was started first of the borders, then of the whole of Russia, according to the subdivisions: narody (peoples), narodnosty (underdeveloped peoples), nacional'nosty (Nationality), natsyj (nations), tribes (tribe). She was encouraged, if not forced, to form her own culture and to learn the native language. However, the NEP did not foresee a hierarchy of ethnic groups - the USSR was one communal "In which each family had the right to have a room of its own, and it was accessed only through free national self-determination to regain confidence in the largest and most impressive nations" [12]. That of the 'Russian' was therefore a politically empty category: the Russians remained in a special position - on the one hand, national minorities in areas not their own, on the other, the absence of national rights or opportunities in Russia. During the NEP, on the other hand, backward nations were taken into consideration, but at the end of the NEP (1928) these "backward" nations were no longer tolerated.

The Stalinist line won in the late 20s. The administrative division of Russia into national areas and districts had to reflect the ethnic composition of the respective territories. This was originally meant to guarantee the influence of individual peoples on local development, which never took place. On the contrary, the rigorous application of class law has overturned the social model of the indigenous population. Their natural leaders, wealthy reindeer owners and shamans, for example, were seen as exploiters and excluded from political positions, while the elected youth of the "working class" were often not competent nor expected from their fellow tribesmen to make decisions about their possessions.

In the 20s there were a number of initiatives to compensate for the economic loss suffered by the indigenous population during the civil war, such as economic support, tax exemption for minorities, building support centers, etc. The establishment of the new Soviet regime meant that all positions at the provincial level and some positions at the district level were taken over by Communists from Southern Siberia or European Russia, most of whom were former Red Army commanders. Their first encounter with the natives of the North was a terrible shock to what they saw as appalling backwardness and miserable living conditions. In a world divided into "poor" and "bad" people, there was no doubt which of these two categories belonged to the Chukchi and other nomadic "alien" peoples. Not only were they all poor, but they were the most exploited and oppressed of the poor. It was equally obvious that the "bad" people were represented by the traders, be they old or new settlers, Americans, Chinese to Japanese. The solution was clear: most of the provincial revolutionary committees, executive committees and even extraordinary conferences promulgated decrees that introduced full legal equality, nationalizing large merchants and drastically limiting the activity of small traders. All traders had to obtain special permits and had to have their price list approved by the police or revolutionary committees. Once they were in a native settlement, they had to show local officials their permits and price lists, and, once permission was obtained, engage in honest and orderly trade.

However, this approach involved a number of problems to contend with; first of all, in many areas no one could take the place of local merchants. More importantly, the new policy presupposed the existence of an army of conscientious officers, who were supposed to educate nomads and generally protect poor people from bad people. However, these officers were hard to find: the few revolutionaries who paved the way for Soviet power in the Far North had no intention of staying there. In any case, if the natives could not take care of themselves, any policy towards them had to be carried out by the local Russians. The improvement in the economic position of the Russian colonists was made easier by the de facto cancellation of the Speranskii statute, which guaranteed autonomous native administration, and the liquidation of the "alien" (inorodsky) as a separate legal category. At the same time, any suggestion that this independence be legalized to reflect and protect the interests of the indigenous population met with fierce resistance. In 1922 Petr Sosunov, the head of the Polar Subcommittee of the Commissariat of Nationalities, was sent to the province of Tyumen to organize a conference on national minorities of the lower region of 0b. The conference adopted a resolution calling for a new administrative unit of Tobolsk'North. As some native delegates said, "Russian exploitation could only be overcome through the creation of our independent government, which would defend its nations and try to give the masses a ray of enlightenment and develop their way of life."

Yakut, illustration taken from Peoples of Russia. Ethnographic Essays, 1880

Sosunov was later arrested and sent to jail for attempting to turn the far north into an autonomous region. [13]. The most common objection to native self-government was the alleged inability of the "northern tribes" to manage their own affairs. Another increasingly popular motivation appealed to the urgent national need for large-scale economic development. According to the executive committee of the Tomsk province, “State policy in the Narym Area should encourage the colonization by the Russian population. Only the settlement is capable of bringing the area back to life. The separation as an autonomous "alien" province would condemn it to remain uninhabited and to live outside the state for many years to come ". As a result, in many areas native settlements and encampments were routinely looted by traveling groups of government officials. The situation was complicated by the ignorance of the new leaders regarding the economy of the natives and the unwillingness of the same to resume the traditional practices of providing long-term credit to hunters. Around 1921 more and more reports on the plight of the peoples of the north began to reach the only body in Moscow that could have a claim on jurisdiction with respect to this matter - The People's Commissariat of Nationalities (Narkommnats) [14].

Despite the continuing unrest in Central Asia, the growing discontent in Transcaucasia and Ukraine, kept the People's Commissar Stalin and his staff already quite busy, the urgent reports from Siberia required their attention at least. The authors of the reports (many of them professional ethnographers) insisted that despite their small size and apparent political irrelevance, the native populations of Siberia held the key to the economic development of at least one third of the country's territory. Scientists assured bureaucrats that protecting the underdeveloped northern tribes was by no means an act of charity - or even class solidarity. Indeed, they argued that it was a matter of extreme urgency and of national importance. The North possessed enormous animal and mineral resources, and only the natives were able to make the most of these resources; therefore, their disappearance could have transformed a potentially rich territory into a huge, unproductive icy expanse. But what could actually be done? Not only was information regarding the northern regions scarce and unreliable; theorizing about the peoples of the Arctic was by no means easier than trying to administer them through the Siberian Office of the Commissariat (Commissariat's Siberian Office). The term "aliens" (inorodtsy) was replaced by various combinations which usually included the word "native" (tuzemtsy, tuzemnyi), but the effort to integrate them into the conceptual framework of the “NATION QUESTION” turned out to be extremely complicated [15].

In classical Marxism, the only significant differences were those of class. Capitalists would ignore national borders in pursuit of profit and proletarians of all countries would unite to oppose capitalism. Even the "classics of Marxism", however, spoke of the Irish and the Poles in terms of real historical agents, and by the time of the Russian Revolution capitalism had become "Imperialism" and nationality had become a "question": the answer of the The Bolsheviks to this problem was to recognize nationalities as "objective" entities and enumerate them as allies in the common struggle against oppression. In Stalin's words: "A nation can organize its life as it sees fit. It has the right to enter into federal relations with other nations. He has the right to secede. Nations are sovereign and all nations are equal" [16]. Nations were real, all real nations were sovereign, and all sovereign nations had the right to political self-determination over their territory. Nations without territory were not real; all territorial borders could be divided into artificial and natural borders (those based on "popular sympathies"). If all this required the creation of unlimited "national autonomous districts", then proletarian society would consist of unlimited autonomous national districts - however small and however non-proletarian.

Why should these concessions have been given support to what was ultimately nothing more than a "philistine ideal" that would slow down the transformation (economic, social and cultural) that Marxism-Leninism set itself as its goal? Such a question carries with it numerous reasons. First, neither the peasantry nor the proletariat could become Communists without the special leadership of the Communist Party. And if they spoke different languages, then the party proselytes would have to speak a wide range of different languages, thus adapting to national and local demands. For Lenin, language represented a totally transparent conduct: Marxist schools had the same Marxist curriculum regardless of the language used. Another reason for Lenin and Stalin's insistence on national self-determination lay in the distinction they drew between the nationalism of the oppressing nations (the so-called "great Chauvinist power") and the nationalism of the oppressed nations (ie nationalism proper). . The first was a "bad habit" which could be eradicated through the revolutionary effort of the proletariat; the second was an understandable reaction to oppression that could only be softened by sensitivity and tact. The gift of national self-determination was therefore a gesture of repentance that would eventually lead to national forgiveness, an end to nationalist paranoia and an end to national differences.

Yakuto village, illustration taken from Peoples of Russia. Ethnographic Essays, 1880

When the proletarian revolution finally came, it appeared to be as national as it was proletarian. The first Bolshevik decrees described the victorious masses as "people" and "nations" with rights; they proclaimed all people equal and sovereign; they guaranteed their sovereignty through an ethno-territorial federation and guaranteed the right to secession; they approved the free development of national minorities and ethnic groups; they pledged to respect national beliefs, customs and institutions. For the end of the war the need for local allies and the recognition of existing national entities combined with the principle of producing an assortment of legally and ethically recognized Soviet republics, autonomous republics, autonomous regions and workers' communes. Some "Internationalist" Left Communists were not at all happy with the turn of events, but Lenin defeated them at the Eighth Party Congress by insisting that nations existed in nature and that "not recognizing something that is out there is impossible: we will be forced to recognize him "[17]. In addition to being "out there", the various nationalities had suffered such inflexible national oppression that as a natural consequence, they harbored a deep hatred of the Russians such that any sort of linguistic and territorial autonomy would be seen as a chauvinistic attempt to preserve the Russian Empire ".

As Stalin said, "the essence of the national question of the USSR consists in the need to eliminate the backwardness (economic, political and cultural) that nationalities had inherited from the past, in order to allow the backward peoples to catch up with the Russia". To do this, the Party must help these Nationalities “(a) develop and strengthen their Soviet statehood in the form that would best correspond to the national physiognomy of these peoples; (b) introduce their own courts and governing bodies which would function in their respective native languages and consist of local personalities familiar with the life and mentality of the local population (c) develop their local press, schools, theaters, clubs and others cultural and educational institutions in native languages "(p.144) [18]. Nationality equaled backwardness, but backwardness did not necessarily equal nationality: in the Bolshevism worldview, backwardness was much deeper, much older, and much more central. It provided the officially unrecognized difference between Marxism and Leninism, described Russia as outside the party and defined the "East" as opposed to the "West". However, some types of backwardness were more backward than others; what about those areas of the empire that had been dormant for most of human history and knew nothing of agriculture?

For Lenin, however, also the "absolute brutality" of the peoples of the North had its usefulness, since if imperialism stood for global capitalism, then "the backwardness of the masses of the East" represented the new global proletarians. For this reason the peoples of the North were for Lenin the natural allies of the revolutionary proletarians of the West. For this union to be stabilized, Europeans had to provide their backward brothers with disinterested cultural assistance and extend to them the promise of national self-determination as well: if Russia could be liberated from rural peasant life, then, with a little extra effort, the savages could be saved from their backwardness and brutality. To achieve this, the Tenth Party Congress prescribed industrial development, class differentiation imposed from above, and in cases of natives threatened by extinction, protection from Russian colonialism. The central objective of the Party was to overcome economic backwardness by transferring factories to the sources of raw materials, and to overcome social backwardness by depriving all native exploiters of their influence over the masses.. This was the ideological context in which the Commissariat of Nationalities found itself operating: the problem of nationalities had to be solved with autonomy, and the problem of backwardness from direct central intervention.

But during the 30s, under Stalin's dictatorship, most of the economic and social structure that might still have been intact was destroyed. Large-scale industrialization of the Soviet Union needed the resources of the North: large-scale fishing blocked indigenous access to many rivers, the food industry turned huge areas into pastures, forests were destroyed to make room for mines and hydroelectric plants. Indigenous peoples were never involved. Their economies collapsed without being replaced by new job opportunities. The big companies imported their own workers and technicians or used prisoners from the gulags, the forced labor camps set up by Stalin. All these foreigners were not under the jurisdiction of the local soviet. Stalin's rise to power represented a radical worsening of their situation for the indigenous peoples. In their territories, rich in mineral resources and timber, a wild industrialization made its way in a big way, without any regard for the fragility of the ecosystem in the Arctic areas. Faced with the rise of roads, mines, oil wells, factories, the traditional activities of the indigenous people had to withdraw to make room for the mining, farming and fishing industries. Large areas were cleared, industrial waste was poured into rivers, the water cycle was interfered with, and massive oil pollution was caused. The workers were mistreated when not recruited into the gulags, so that many indigenous people lost their jobs. The land was expropriated by the state, its inhabitants transferred to other territories. In 1937 a Soviet decree imposed the exclusive use of the Cyrillic alphabet for all languages of the USSR.

Starting in 1957, any teacher could be arrested if they continued to speak the indigenous language outside of school. Parents were forced to baptize their children with Russian names. The government forced many nomads to become sedentary. Small villagers were forced to move to large towns because public services had been closed. Today it is common for only the elderly to know their mother tongue, while various languages are about to disappear. State-owned companies imported their workers who were outside the jurisdiction of local authorities. The natives whose livelihoods were destroyed became dependent on service functions for foreign industry or sought refuge in more hostile mountainous and tundra areas. Traditional occupations of herding, hunting and reindeer fishing were forcibly transformed into collective farms, kolkhoz, throughout the Soviet Union. Local uprisings were suppressed and severely punished, for example, in the Nenets and Taymyr areas in 1930-32. Several national areas were dissolved and the North was divided between various ministries.

There was no monitoring agency that could oversee the continued colonization and exploitation of the land and the fate of its native inhabitants. Plus, of course, in 1941 Russia was involved in the Second World War and many natives were sent to fight at the front. The lack of young men for domestic occupations has mainly affected vulnerable small indigenous societies. Too many domestic animals had to be slaughtered and river mouths were depleted of fish in the fight against hunger. The thousands of men returning from the front had changed their social attitudes and thus accelerated cultural assimilation. European immigration to Siberia has increased. In the 50s and 60s a large-scale campaign was pursued to lead peoples into "modern socialist civilization", with forcible relocation to urban or semi-urban areas. The execution consisted in depriving rural areas of hospitals, schools and shops. Nomads were officially declared primitive human beings and were invited to settle.

5. CONCLUSIONS

At the end of the 50s the government initiated a policy of forced settlement of the indigenous population in the major cities of Siberia. This policy favored the definitive loss of cultural identity and the spread of alcoholism and crime. The boom in the petroleum oil industry that began in the 60s took other territories away from a whole series of ethnic groups (Nenzi, Oroki, Evenki and others). But there was not enough work in the new settlements to replace the lost traditional occupations. The consequences for many were a further loss of economic capacity and social structure, increased crime rates and alcohol abuse. In 1980 the ethnic-based administrative areas ceased, the word "minorities" was removed from the legislative texts and the local administrative bodies lost all functions except the advisory ones. The educational policies of Soviet Russia towards indigenous peoples had changed dramatically. The centralistic evolution of the Soviet administrative system in the early eighties, when even the word "minority" was deleted from the legal texts, removed the last vestiges of self-government from the local soviets, maintaining a mere consultative function. Until the end of the 80s the Soviet government continued the savage industrialization of the Northern Territories. Deforestation and the extraction of oil and natural gas continued at full speed. Indigenous peoples lost vast areas of grazing. Only in 1989 did some peoples begin to organize themselves into associations.

As for education, Il school system it was renovated and underwent a major development in the 20s. Linguists have developed alphabets for all language groups, with special letters based on the Latin alphabet. Illiteracy has decreased significantly. In 1937, Stalin imposed the application of the Cyrillic alphabet for all languages and linguists who had worked on custom alphabets were imprisoned as public enemies, initiating a policy that aimed to erase all ethnic identity. After 1957, teachers were even punished for talking to non-Russian pupils outside of their native language classes. The college system (along the lines of boarding schools of Canada) - originally intended to give nomadic children the opportunity for higher education - had a destructive influence on minority cultures when it was extended to the primary school level. Children grew up distant from their parents and returned at the age of 16-17 as almost complete strangers with often weakened ties to their ethnicity and language, and with almost no practical skills for traditional occupations. As a result, the system favored assimilation into Russian society. The decrease in people using or understanding their mother tongue is enormous. Today, the older generation - over 50 - carry on the language. However, it would be wrong to overlook the positive developments during the Soviet era. An important example is that the role of women in society has benefited, as many taboos have been broken. Other examples were the improvement of health care, the reduction of infant mortality, etc.

In conclusion, the experience of the indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic under Tsarist and Soviet imperialism certainly cannot be said to be positive. As Russel Means said in one of his famous speeches, “The real nature of a European revolutionary doctrine cannot be judged on the basis of the changes it proposes to effect within European society and power structures. It can only be judged by the effects it will have on non-European peoples " [19]. In this sense, revolutionary Marxism has committed itself to an even higher degree to the perpetuation and perfection of the industrial process: it simply offers to redistribute the profits resulting from this industrialization to a larger sector of the population. But from a practical point of view, the history of Marxism towards non-European populations has proved to be as harmful as that of capitalism: in this sense, it is fully part of that process of "de-spiritualization" and rationalization of being which characterized the Western philosophical experience that reached Marx starting from Plato. Unfortunately, the result is evident: where it came to power, real socialism intensified that process of industrialization that began with the Industrial Revolution, achieving in the space of 60 what Capitalism had taken more than two centuries to achieve. The territory of the USSR contained a number of tribal peoples who were crushed to make way for factories.

The Soviets refer to this problem as the "National question" - the question of whether or not these tribal peoples had the right to exist as peoples - and decided that tribal peoples were an acceptable sacrifice for industrial needs. I look to the People's Republic of China and see the same thing. I look to Vietnam and I see the Marxists imposing industrial order and eradicating the indigenous peoples of the mountains. I have heard a leading Soviet scientist say that when uranium is depleted, alternatives will be found. I see the Vietnamese taking possession of a nuclear power plant abandoned by the American military forces: did they dismantle it or destroy it? No: they are using it. I see China detonating atomic bombs, developing nuclear reactors, preparing a space program In order to colonize and exploit the planets just as Europeans have colonized and exploited the globe. It's the same old story, but this time at a faster pace.

Note:

[1] To learn more about the ethnographic distribution of the Siberian indigenous peoples, see the RAIPON website Главная - Ассоциация коренных малочисленных народов Севера, Сибири и Дальнего Востока РФ (raipon.info)

[2] Vitebsky, Piers. The reindeer people: living with animals and spirits in Siberia. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006.

[3] To learn more about Shamanism and the traditional religions of indigenous peoples: Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Vol. 76. Princeton University Press, 2020; Comba, Henry. Men and bears: morphology of the wild. University Press Academy, 2015; Vitebsky, Piers. shamanismUniversity of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

[4] To deepen the relationship between center and periphery in the Russian Empire see Kappeler, Andreas. "Center and periphery in the Russian Empire, 1870-1914." Italian historical journal 115.2 (2003): 419-438J. Burbank, M. Von Hagen Russian Empire, Space, People, Power, 1700-1930, Bloomington, Indiana UP, 2007

[5] For further information: Bassin, Mark. "Turner, Solov'ev, and the" Frontier Hypothesis ": The Nationalist Signification of Open Spaces." The Journal of Modern History 65.3 (1993): 473-511; Smith, Henry Nash. "The frontier hypothesis and the myth of the west." American Quarterly 2.1 (1950): 3-11.

[6] To deepen the relationship between the Tsarist Imerus and the Slezkine indigenous peoples, Yuri. "Arctic mirrors." Arctic Mirrors. Cornell University Press, 2016.

[7] Jones, Ryan. “Willard Sunderland, Taming the Wild Field: Colonization and Empire on the Russian Steppe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. 264 pp. ISBN: 0-8014-4209-5 (hbk.). " Itinerary 30.1 (2006): 126-127.

[8] To deepen the question of territorial integrity in the Russian Empire - Wortman, Richard. "The" Integrity "(Tselost ') of the State in Imperial Russian Representation." Ab Empire 2011.2 (2011): 20-45.

[9] Jones, Ryan. “Willard Sunderland, Taming the Wild Field: Colonization and Empire on the Russian Steppe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. 264 pp. ISBN: 0-8014-4209-5 (hbk.). " Itinerary 30.1 (2006): 126-127. To deepen the relationship between center and periphery in the Russian Empire see Kappeler, Andreas. "Center and periphery in the Russian Empire, 1870-1914." Italian historical magazine 115.2 (2003): 419-438.

[10] To deepen the relationship of the Soviet state with non-Russian nationalities Martin, Terry Dean. The affirmative action empire: nations and nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University Press, 2001.

[11] Slezkine, Yuri. "Arctic mirrors." Arctic Mirrors. Cornell University Press, 2016.

[12] Slezkine, Yuri. "The USSR as a communal apartment, or how a socialist state promoted ethnic particularism." Slavic review 53.2 (1994): 414-452.

[13] Slezkine, Yuri. "Arctic mirrors." Arctic Mirrors. Cornell University Press, 2016.p.136.

[14] Ibid.

[15] To deepen the debate on the national question: Connor, Walker. The national question in Marxist-Leninist theory and strategy. Vol. 6. No. 8. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984; Von Hagen, Mark. “The Great Challenge: Nationalities and the Bolshevik State, 1917-1930. By Hélène Carrère d'Encausse. Trans. Nancy Festinger. New York: Holmes and Meier, 1992. Maps. Bibliography. Index. " Slavic Review 53.1 (1994): 234-236; Pipes, Richard. The Formation of the Soviet Union: Communism and Nationalism, 1917-1923. Vol. 13. Harvard University Press, 1964.

[16] Stalin, Iosif Vissarionovich. Marxism and the national question. Italian cultural editions, 1939. See also Konrad, Helmut. Between “Little International” and Great Power Politics: Austro-Marxism and Stalinism on the National Question. na, 1992.

[17] Slezkine, Yuri. "Arctic mirrors." Arctic Mirrors. Cornell University Press, 2016, p.143.

[18] For more information on "Korenizacija" see: Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, Equality, Efficiency, and Politics in Soviet Bilingual Education Policy, 1934-1980, in American Political Science Review, vol. 78, n. 4, December 1984, pp. 1019-1039, DOI: 10.2307 / 1955805. Retrieved September 16, 2018; Chris J. Chulos and Timo Piirainen, The fall of an empire, the birth of a nation: national identities in Russia, Ashgate, 2000, ISBN 1855219026; Terry Martin, The affirmative action empire: nations and nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939, Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 9781501713323; Yuri Slezkine, The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism, in Slavic Review, vol. 53, n. 2, 1994 / ed, pp. 414452, DOI: 10.2307 / 2501300; Ronald Grigor Suny and Terry Martin, A state of nations: empire and nation-making in the age of Lenin and Stalin, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 9780195349351.

[19] Full article The speech of Russel Means | Italian Friends of Nature Group.

Bibliography:

Ronald Grigor Suny and Terry Martin, A state of nations: empire and nation-making in the age of Lenin and Stalin, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBNs9780195349351.

Martin, Terry Dean. The affirmative action empire: nations and nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Cornell University Press, 2001.

Kappeler, Andreas. "Center and periphery in the Russian Empire, 1870-1914." Italian historical journal 115.2 (2003): 419-438.

J. Burbank, M. Von Hagen Russian Empire, Space, People, Power, 1700-1930, Bloomington, Indiana UP, 2007

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Vol. 76. Princeton University Press, 2020.

Connor, Walker. The national question in Marxist-Leninist theory and strategy. Vol. 6. No. 8. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984. -

Comba, Enrico. Men and bears: morphology of the wild. University Press Academy, 2015.

Chris J. Chulos and Timo Piirainen, The fall of an empire, the birth of a nation: national identities in Russia, Ashgate, 2000, ISBNs1855219026.

Bassin, Mark. "Turner, Solov'ev, and the" Frontier Hypothesis ": The Nationalist Signification of Open Spaces." The Journal of Modern History 65.3 (1993): 473-511.

Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, Equality, Efficiency, and Politics in Soviet Bilingual Education Policy, 1934-1980, in American Political Science Review, vol. 78, n. 4, December 1984, pp. 1019-1039, DOI:10.2307/1955805. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

Slezkine, Yuri. "Arctic mirrors." Arctic Mirrors. Cornell University Press, 2016.

Slezkine, Yuri. "The USSR as a communal apartment, or how a socialist state promoted ethnic particularism." Slavic review 53.2 (1994): 414-452.

Smith, Henry Nash. "The frontier hypothesis and the myth of the west." American Quarterly 2.1 (1950): 3-11.

Stalin, Iosif Vissarionovič. Marxism and the national question. Italian cultural editions, 1939.

Terry Martin, The affirmative action empire: nations and nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939, Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBNs9781501713323.

See also Konrad, Helmut. Between “Little International” and Great Power Politics: Austro-Marxism and Stalinism on the National Question. na, 1992.

Vitebsky, Piers. Shamanism. University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Vitebsky, Piers. The reindeer people: living with animals and spirits in Siberia. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006.

Yuri Slezkine, The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism, in Slavic Review, vol. 53, n. 2, 1994 / ed, pp. 414452, DOI:10.2307/2501300

Wortman, Richard. "The" Integrity "(Tselost ') of the State in Imperial Russian Representation." Ab Imperio 2011.2 (2011): 20-45.

W. Sunderland, Taming the Wild Field. Colonization and Empire on the Russian Steppe, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2004

Von Hagen, Mark. “The Great Challenge: Nationalities and the Bolshevik State, 1917-1930. By Hélène Carrère d'Encausse. Trans. Nancy Festinger. New York: Holmes and Meier, 1992. Maps. Bibliography. Index. " Slavic Review 53.1 (1994): 234-236.

Pipes, Richard. The Formation of the Soviet Union: communism and nationalism, 1917-1923. Vol. 13. Harvard University Press, 1964.

Thanks, finally a precise description in Italian! I am a Turkic speaker, we are the real natives