Hallucinated and imaginative painter, multifaceted and visionary artist, forced by continuous nervous breakdowns to prolonged stays in nursing homes and psychiatric hospitals, Mervyn Peake entrusts the written word with the task of exorcising the dark obsessions that will eventually devour him. On the stormy sea of a dreamlike universe both nourished and threatened by the excesses of a self-destructive insanity, the arabesques, acrobatic architectures of the castle of Gormenghast, monstrous, tangled, gigantic concretion of the uncontrollable fears that grip the soul of the English writer.

di Paul Mathlouthi

cover: Marvyn Peake photographed in 1946

Is there a correlation between Genius and Madness? Karl Jaspers, author of an essay that has now become an indispensable classic on the subject, would answer without hesitation that one cannot exist without the other. If the German philosopher's attention focuses in a particular way on the figure of Van Gogh as a paradigm of his argument, literature and philosophy have offered no less emblematic examples of the irrefutability of this dialectical dichotomy.

The lyrics of Holderlin would they perhaps have that dizzying, prophetic brightness if the poet, besieged by madness, had not chosen to condemn himself to the darkness of a cloistered existence? Dovstoevskij would have plumbed with the same surgical precision the unfathomable depths of the Abyss on the edge of which Raskol'nikov, Stravrogin and Golyadkin, his tormented alter egos, overlook, if the repeated attacks of epilepsy had not forced him to a daily confrontation with the monsters that make the certainties of Reason waver? Friedrich Nietzsche would he have been struck by the intuition of the Eternal Return or would he have prophesied the death of God if the insidious demon of the swoon had not taken possession of his portentous mind? Readers know in their hearts that the answer to these questions is actually a foregone conclusion.

From the Ancient Greece to the glacial solitudes of Siberian taiga, the traditional cultures of all times and latitudes share the idea that madness is a manifestation of the Sacred, a means through which the otherworldly powers offer initiates who are affected by it, be they heroes or oracles, the possibility of accessing a different level of consciousness and writing, which has always maintained underground ties with the divine, becomes a liminal experience par excellence, the main access key to this secret garden strictly closed to the profane [1].

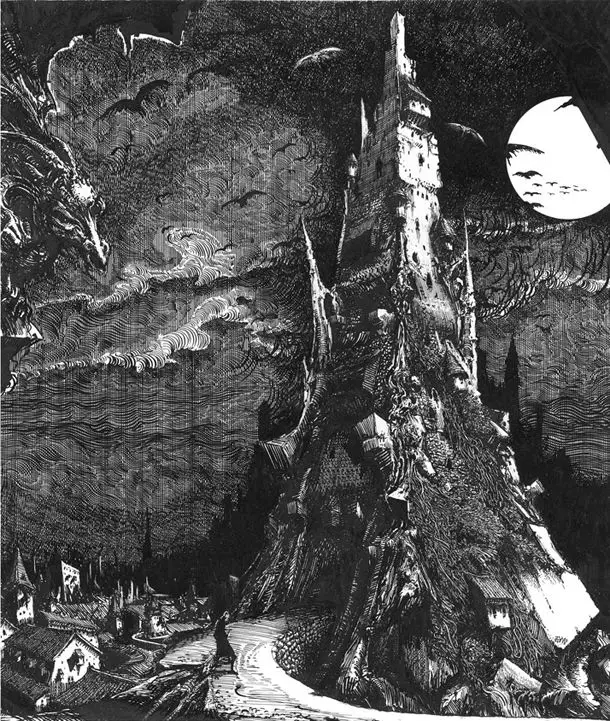

Hallucinated and imaginative painter, multifaceted and visionary artist, imaginative illustrator of the masterpieces of Lewis Carroll and Robert Louis Stevenson as well as of the most famous British edition of the tales of the Brothers Grimm, forced by continuous nervous breakdowns to prolonged stays in nursing homes and psychiatric hospitals, Mervyn Peake (1911 - 1968) entrusts precisely to the written word the task of exorcising the dark obsessions that will eventually devour him. On the stormy sea of a dream universe at the same time nourished and threatened by the excesses of a self-destructive insanity, the arabesques arch, acrobatic architecture of Gormenghast Castle, monstrous, tangled, gigantic concretion of the uncontrollable fears that grip the soul of the English writer, in the shadow of which the tragic epic of the ancient family of De 'Lamenti takes place, linked since time immemorial to the fate of the manor in which he lives detached from the reality that incessantly agitates beyond the impregnable ramparts.

“High and sinister walls like quays of piers, or secret for the condemned, soared in the watery air or curved majestically in prodigious arches of cruel stone […]. Buttresses and tall buildings loomed like the carcasses of wrecked ships, or sea monsters with dripping mouths and fronts […]. The castle rose above the horizon like the gigantic cliff of a continent; a shoreline gnawed by innumerable coves and bitten deep by shady bays. A continent, with a cluster of islands off the coast; islands of all shapes that a tower can take; entire archipelagos; isthmuses and promontories; gloomy peninsulas of jagged stone - an inexhaustible panorama, mirrored in every detail by the fearful depths below […]. On the irregular roofs fell [...] the shadow of Torrione delle Selci which, here and there dappled with black ivy, rose from the fists of knotty stones like a mutilated finger, pointing like a blasphemy towards the sky. "

[2]

Precisely in this inaccessible place, an elitist hermitage reserved for the cult of the memories of the Ancestors, on a night illuminated by the tainted glow of the fire that blazes in the halls of the library, the Count Sepulcrio who in an attempt to escape the grip of the flames reaches the highest point of the Torrione and is attacked by the owls that lurk there, which tear the flesh with brutal, voracious greed, precipitating its body into the escarpment below. It is a claustrophobic world that described by Mervyn Peake in his monumental trilogy, studded with inextricable labyrinths, interminable corridors, inviolable dungeons, underground recesses, where a meticulous ritual punctuates down to the most insignificant details the times and ways of a rigidly hierarchical social structure that cannot be modified, at the top of which are the Masters of the Rite, Agrimonio and Barbican, grotesque figures made repugnant by the toxic contiguity with the power that in the name they recall the Dantesque Demons huddled on the walls of Dis, deformed and lame beings whose lugubrious step, amplified out of all proportion by the echo, echoes at every foot pushed under the vaults of the castle, heralding their arrival to anyone.

Panicked, the dignitaries gathered at the news of Sepulcrio's death to express their condolences to the imperturbable Countess Gertrude and pay homage to little Tito, the future heir to the throne, with an act of submission, begin to wonder how it is possible that in a place in to which every fact, every event, every gesture, even the confidences that the servants exchange whispering to each other with the complicity of the night is obsessively screened and weighed so that it does not break the very complicated ceremonial, someone may have attacked none other than the life of the supreme authority . Gormenghast is not a whitewashed tomb, but a "stone anthill" where humanity constantly swarms in eternal turmoil, driven mad by the mandatory obligation that prevents anyone from abandoning its borders. The fortress seems to be endowed with an obscure will of its own, it literally feeds on the vital force of those who live there and the forced coexistence within the narrow spaces of a cloistered existence constantly conducted away from sunlight, necessarily feeds the unfolding of the most turbid and oblique aspirations of the soul.

It is therefore not surprising that in the abyssal, incandescent depths of the Grande Cucina, an outcast, a pariah like Ferraguzzo, secretly cultivates warlike intentions of social revenge. The lean and vigorous physique tempered by fatigue, the disheveled reddish hair to halo a rounded skull with Lombrosian features, two haunted and very mobile eyes, attentive to every imperceptible change, the unrecognized boy escapes with a stratagem the humiliating tasks to which, according to the iron logic that governs the manor, its plebeian origins would chain it to life, winning the favor of the vain court doctor Floristrazio who introduces him into the secret rooms. It is the sign of one alchemical mutation who suddenly reveals his true nature: leaning on a stick with an armed soul, accompanied by a monkey named Lucifer, the enterprising upstart, protected by the benevolence of the most influential members of the court, works with feverish, meticulous diligence in every corner of the castle, always preceded by the gloomy omen of its shadow which, wrapping it like a cloak, towers in the chiaroscuro of the torches sliding along the walls and colonnades of the cloisters. To anyone who meets him, persuasive voice and winking, dispenses advice, offers help, guarantees protection and, with Machiavellian cunning, moves the various actors of this glowing baroque caravanserai against each other, as in a gigantic game of chess played. by figures in flesh and blood.

She seduces the young Fuchsia, sister of Tito, a rural creature, an indocile and moody spirit, she blows on the fire of resentment that hatches in the hearts of the twins Cora and Clarice, bitter spinsters hostile to Sepulcrio who reproach them for not wanting to take them into consideration due to their own rank and he uses them as material executors of the fire in which the Count will find his death, only to then lock them up in the Room of the Roots; he kills Agrimonio and Barbican without hesitation, finally finding himself the sole depositary, keeper and interpreter of Gormenghast's laws. A full-scale climb to Heaven, pursued with lucid coldness and ruthless determination, to which only the legitimate heir, who had lived up to that moment in voluntary exile in the Bramble Forest under the watchful gaze of the elderly Lisca, notable of the old guard who remained faithful to the memory of his father, he will be able to put a stop, eliminating Ferraguzzo in a fight to the death which, by restoring the line of succession, will restore the correct order of events.

A cult writer whose works in England are the subject of successful cinematographic transpositions and have inspired the fervent imagination of designers of the caliber of Alan Lee, Mervyn Peake has met in our country a rather stingy reception of compliments from specialist critics, although at doing the honors was none other than Roberto Calaso, who deserves the credit for having included this at least controversial author in the golden canon of his prestigious catalog.

The few who in our latitudes have ventured to explore the twisted geometries of Gormenghast they expressed a certain embarrassment in their attempt to classify this extremely articulate and complex work within the parameters of the codified literary genres. However, everyone seems to agree that it is not a fantasy novel, whereas with this term widely abused and indeed inaccurate, today it is customary to extensively indicate the epic saga. This judgment, in my humble opinion, undoubtedly hasty when not superficial given that, upon careful analysis, it is easy to find how the archetypal elements of the Quest, as the English call it, that is to say the Search of a chivalrous type, are actually present unequivocally.

Behind the vestments of a scenographic prose, polyphonic, overflowing with adjectives to the point of paroxysm, Mervyn Peake does nothing but describe the fall of a Kingdom. If it were possible to reduce the plot to its primeval essentiality, freeing it from stylistic trappings and superstructures of any kind, we would find ourselves in the presence of a theatrical representation with an Elizabethan flavor, where a legitimate Sovereign, Sepulcrus, the last representative of an ancient lineage whose pride is now an exhausted and lifeless memory but no less binding for those who guard its vestiges and cultivate its memory, finds death by betrayal at the hands of an Antagonist who in his salient characteristics symbolizes the plastic projection of a foreign universe of values and indeed I would say antithetical to the world of Tradition.

Ferraguzzo is not only cruel (which, in itself, would not necessarily be a defect), but he is above all a double agent, intimidating, arrogant, liar on the edge of the pathological, he has a natural inclination to duplicity typical of the conspiratorial soul: he exhibits that is, in the highest degree the qualities of the modern demagogue. A telluric figure who knowingly works in favor of Chaos. He is ultimately a foreshadowing of the Kali Yuga. In this perspective, his killing by Tito, the designated heir of Gormenghast, takes on the meaning of a symbolic gesture, an apotropaic action aimed at propitiating the recomposition of the lost unity of the Whole and, with it, the advent of a further beginning. , a new Golden Age, respecting the one that Mircea eliade he would call the "sphericity of Time" inherent in premodern cultures.

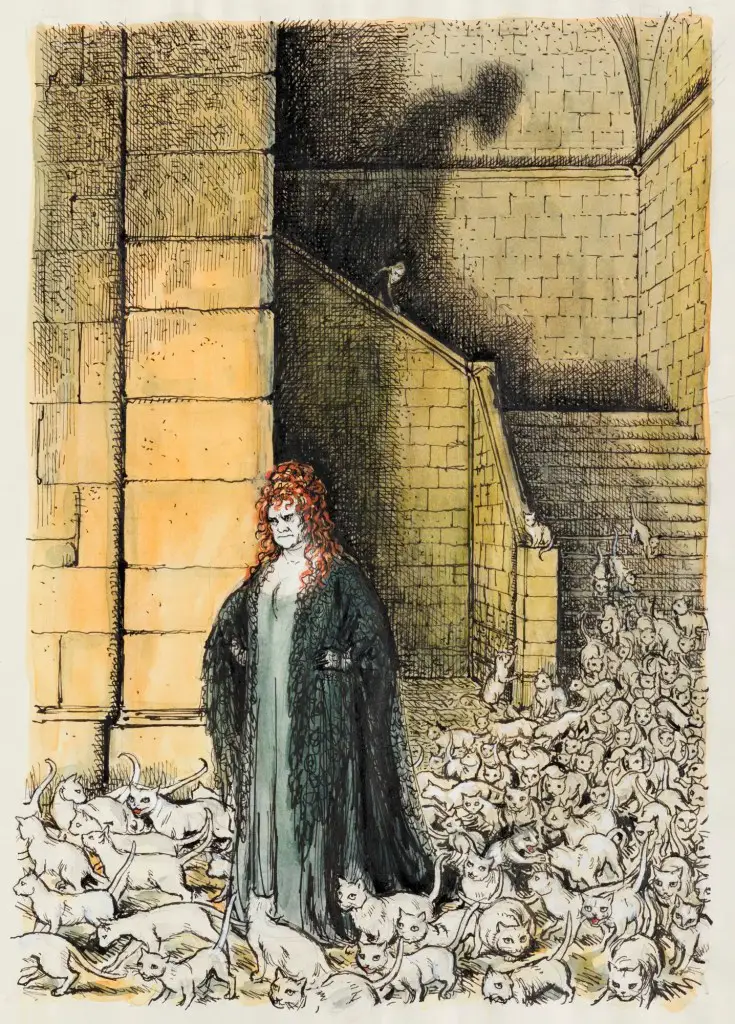

If these elements do not impose themselves on the reader's attention at first, this is due to the fact that, in compliance with the aesthetic and stylistic dictates of Surrealism to which Mervyn Peake refers, the narrative plans are disjointed in favor of the irruption of elements drawn from the sphere of the dream, from the unexplored territories of the unconscious. Here then is that the Countess Gertrude appears to us seated on her throne of cushions cloaked in a robe made up of hundreds of thousands of live cats, which move in unison in symbiosis with their mistress, while birds of all shapes with multicolored feathers nest among the thick curls of her turreted hair ... but this representation does not make her less terrible when she declares with a final tone that "There is no Elsewhere, because everything leads to Gormeghast".

Note:

[1] Karl Jaspers, Genius and Madness. Strindberg and Van Gogh, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milan 2001.

[2] Mervyn Peake, Gormenghast, Adelphi, Milan 2005; p. 32.