Alessandro Bonfanti's study on the Sicilian Magyars of Transylvania continues, this time with an excursus on their enigmatic graphemic system, wrongly mistaken by some scholars for runic. As well as in the previous articles of the series, this time too the Author's analysis will go as far as the Asian steppes.

di Alexander Bonfanti

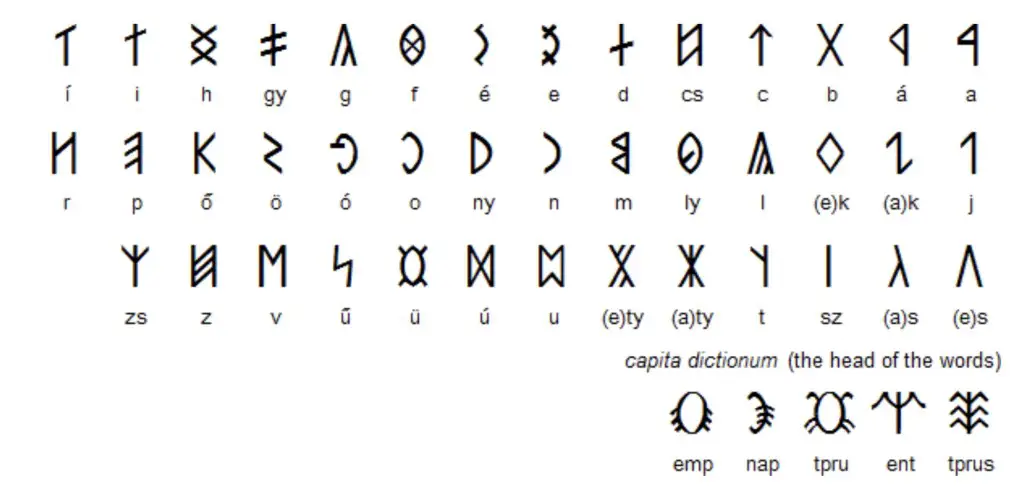

Returning to the Magyar Sicilians from Transylvania, then there is the heated dissertation on the graphemic system still in use by this proud population tenaciously tied to their traditions, that is Székely Rovásírás, wrongly believed and / or mistaken for a runic system. Also on this subject I add all the possible proofs for a refutation (your questions have been many). This ancient Hungarian alphabet, Rovásírás, was used by the Hungarians in the medieval period, between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. of the vulgar era, therefore long before the Kingdom of Hungary began, having arrived in the current area comprising a large part of the sub-Carpathian basin together with this tribe of `` Siculi '' Magyars, who, as already mentioned, they would have taken this name from the place of settlement, which reached as far as present-day Serbia.

The other Magyar tribes wedged themselves into the territory of the Sicilian Magyars, all settling in present-day Hungary, i.e. in ancient Pannonia, a territory which in turn takes its name from the settlement of another population, the Pannonians, who have nothing to do with it. with Finno-Ugric groups. The settlement of the Hungarians has '' cut '' the Magyar Sicilians in two, stemming a part of them in present-day Romania, the other part in present-day Serbia. These '' Sicilians '', who remained '' marginalized '', were able to perfectly preserve all the linguistic archaisms and all the traditional atavisms, including the graphemic system called Rovásírás, still in use in this community and erroneously called the '' old Hungarian runic alphabet ''. But where does this very interesting writing system come from? I begin by reiterating that this is not a runic system absolutely, since runic glyphs, being such, have characteristics that go beyond the merely representative and evocative function of a specific sound produced by the human phonatory apparatus within a spectrum delimiting for articulation, timbre and modulation, ie what is called a phoneme, which is a quality of sound including quantitative vibratory variations (the so-called allophones of the same phoneme or quantifiable intensity gradients). Glyphs are first of all an engraved image, marked on a surface, being Action = Force by one Voluntas = Power, not a sound therefore, absolving the phonic nature only in a second moment: they evoke an image, a concept, a pure logical process, an intuitive lightning. Glyphs are sacred, cosmogonic and theurgic signs. As a means of communication, glyphs can therefore be adapted to the secondary and improper use of evoking a type of sound, a phoneme. But the concrete fact is observable that the glyphs represent all the sounds / phonemes that one wants to attribute to them: every Germanic tribe has given itself over time phonetic values to each glyph, different phonemes therefore variable from tribe to tribe and within a tribe same different phonemes over time. The runic glyphs are therefore real evocative, theurgic symbols, ritual elements that catalyze and emanate: Voluntas, power, Action. I invite you to peer into the Worldview Indo-European.

The Magyar system is only graphemic, ie consisting of signs and vocants only phonemes, in practice an alphabet. Graphemes therefore have no ritual value, but only phonetic value: each grapheme corresponds uniformly to a phoneme, just like our alphabet, just like the one I am using now to write this article, no more and no less. Rovásírás however, it had an origin, like all other things: nihil ex nihilo. But where does it come from then? It is enough to carefully observe the forms of the various graphemes that constitute it. Many of these graphemes come from the runic glyphs used by various peoples of the Germanic group who in their descent towards the South had temporarily settled in the Carpathian area: Goths, Gepids, Lombards, Vandals. These peoples, and among them mostly the Goths, had fairly long contacts with alien peoples, not only Finno-Ugric, including the Magyars, but also with peoples of Ural-Altaic extraction, including the well-known Huns. This contact had his okme in the fifth century. of the vulgar era, but it can be circumscribed between the fourth and fifth centuries, that is, in the time in which the Huns experienced the greatest territorial expansion, bringing with them many related peoples from the Russian steppes, and in the time in which these movements pushed these Hungarians '' Siculi '' to take possession of the area including the current Romania, Hungary and Serbia, from the sub-Carpathian basin to the northern Balkans. This is the '' gestation '' period of Rovásírás, used by all the Hungarians (the ancestors of the current Hungarians) from the 15924th to the XNUMXth century, then supplanted by the Latin one, in turn adapted to better render Magyar phonetics. From this similarity with certain Germanic glyphs, in turn ascribable to the direct influence by acquisition of the latter for the sole profane use, i.e. writing, it has been defined '' Hungarian runic alphabet '' in the Standard ISO XNUMX: ''Old Hungarian Runic''. But it is clear that this is an error. With the founding of the Kingdom of Hungary, following the coronation of Stephen I, who united all the mostly nomadic tribes into one people, Rovásírás it was eliminated by force, but it has fortunately remained in use until now among the Transylvanian Sicilians, the `` marginalized '' Hungarians, who in their isolation have won the centuries-old battle for the survival of their ancestral traditions. It is nice, in fact, to still see road signs of those rural areas written in today Rovásírás, indeed in Székely Rovásírás. We also have evidence of the use by the Magyar Sicilians of this alphabetical system in Chronicle of a certain Simone of Kéza, a text of the XIII century, in which it is reported that the `` Sicilians of Transylvania '' used the same alphabet as the Wallachians (Vlad called the Impaler, the terror of the Turks, alias '' Dracula '', was in fact of Sicilian-Magyar ethnicity). But then the well-known inscription of the Church of Atid dates back to 1668; and then still others that reach up to the nineteenth century, coming from various locations in Romania, such as Sângeorgiu de Mureș, Targu Mures, Field Cross, Kecskemét, Ghindari, Turda, Racu etc. This alphabet also presents some innovations: it has added over all these centuries, until now, variants to better distinguish certain allophones that have evolved within the phonetic system; he added numeral graphemes largely of clear Roman derivation (from 1 to 10, but then graphemes created by themselves were actually used for 50, 100 and 1000); and even new ones to compensate for the loss and / or addition of phonemes due to the chains of traction and thrust to which any language is subject in its evolutionary course. Therefore, this alphabetic system (grapheme = phoneme), as we see it now in the diffusion areas (Romania), is quite new, not really ancient therefore, having been constantly innovated and renewed (or vice versa) over time, up to the present day. . There is a scholar, some András Róna Tas, who said that this alphabetical system would derive from the ancient Mongolian alphabet of Orhon, which in turn would derive from alphabets such as Pahlavi, or Sodgian, or Kharoshthi, and that in turn these alphabets would derive from the alphabet Aramaic; since '' the Magyar peoples would have come into contact with Turkish populations between the 720th and XNUMXth centuries, in fact there were many Hungarian acquisitions from the Turkish ''. But it is enough to observe that the oldest inscription in the Orhon alphabet dates back to the first half of the XNUMXth century, around XNUMX it was vulgar; and then, more importantly, the graphemes of the two alphabetic systems do not correspond, since the phonemes constituting the two languages do not correspond. But also the Mongolian alphabetical system retains a certain Gothic influence, precisely because the people of the Orhon would have been the direct descendants of the Huns, and the Huns, yes, came into contact with the Germanic peoples. Compare the various alphabetic systems mentioned above and then tell me if you find these '' affinities '' that can make you think even vaguely of a direct derivation. Neither places nor times, especially times, do not coincide. The system Rovásírás takes its name from the verb roni '' mark '', taken from the proto-Hungarian and in use since the XNUMXth century, therefore in our era. The various acquisitions of words between one language and another, the so-called '' loans '' (a term that I replace with the more efficient '' acquisition ''), are a common phenomenon, due to mainly commercial exchange or for exercise of an administrative power, without therefore entailing a significant change in the genetic, cultural and spiritual profile of a given population. Today some of us eat a slice of pineapple or a kiwi without losing its phenotypic characteristics. Nobody falls asleep on a `` sofa '' and wakes up Turkic, although the word has Persian origins, therefore always Indo-European. Another example can be found in the coronym of the same Magyar Sicilians present in Romania, Szeklerland, which in Hungarian means '' Territory of the Sicilians '', which certainly does not escape that Earth '' field / territory '', of clear Germanic origin, just compare it with the modern German neighbor Feld and with the farthest modern English field. But neither the Hungarians nor the Magyar Sicilians are of Germanic descent, being only of Adstratic influence.

This Magyar alphabet system was first studied in 1598 by János Telegdi, who described them in the book Rudimenta Priscae Hunnorum Linguae ('' Bases of the ancient language of the Huns ''), showing, in addition to the transliteration of graphemes, also the texts that were written and preserved with this system, such as Christian prayers. All of this maelstrom, all this confusion about the origins of Rovásírás, intended as `` Turkish runic characters '' (sic) is due to two researchers, who at the beginning of the last century tried to trace the origins of this alphabet: Gyula Sebestyén, ethnologist, e Gyula Nemeth, turcologist. The first, Gyula Sebestyén, is the author of two essays: Rovás és rovásírás ('' Runes and runic writing ''), published in 1909, e A magyar rovásírás hiteles emlékei ('' The authentic relics of Hungarian runic script '') published in 1915. Edward D. Rockstein, with his The Mystery of the Székely Runes, Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers, published in 1990.

The alphabet in question has undergone many readjustments, even during that period, precisely in Hungary. Adorján Magyar was the one who from 1915 fought for the use of the alphabet to write today's Hungarian, bringing innovations on it, especially for vowels: new characters to distinguish a da á, as well as e da é, without however making signs that distinguish the morae, that is the vowel lengths. And another, Sándor Forrai, in 1974 introduced innovations to distinguish i da í, o da ó, ö da ő, u da ú, ü da ű. This is because originally many of the inscriptions with the aforementioned alphabetical system lacked vowels, or were rarely written.

The Iron Curtain regime tried in every way to eradicate this system, and after the fall of the Berlin wall and therefore the collapse of the communist system, starting from 1989, the Revival of the Rovásírás. I know that in 2009 the Unicode standardization of this alphabetic system took place. The current alphabet does not yet contain proper graphemes for phonemes dz e cbs, the result of a rather recent refonologization of Hungarian, as well as the Latin graphemes for phonemes q (ie kw), x e y (the latter two are of Hellenic origin) and finally for w (son of the ancient digamma Indo-European), but in Unicode encoding ligatures of graphemes have been accepted (also because they are composed sounds, coming from overlapping phonemes). The system Rovásírás, as tradition dictates, it proceeds from right to left.

But what do the graphemes of the Mongolian empire alphabet of the Göktürk of the Orhon (or Orkhon) Valley have to do with it? Let's see'. This alphabetical system, therefore based on the binomial grapheme = phoneme (and that's it), dates back to the VIII century. of the vulgar era and was used by the Khanates of this kingdom until the 1889th century, always going from right to left. The first discovery of these inscriptions dates back to XNUMX, during the expedition led by the explorer Nikolay Yadrintsev in the Orhon Valley, Mongolia. They were first published by Vasily Radlov, and to follow, in 1893, deciphered by Vilhelm Thomsen, a well-known Danish linguist and philologist. And even in this case there is no shortage of unwise associations to '' other '', as we have previously seen for the ancient Magyar alphabet. And also in this case the same explanation given on the origins of the Magyar alphabet applies. In short, both have a common peri-Carpathian origin, but a different embryogeny, which occurred in different places and times: the first from the encounter between proto-Hungarian groups (don't say `` proto-Hungarian '') and Germanic (mainly Goths and Gepids); the second from the meeting between the Huns and the same Germanic groups. The real problem to be solved is in fact that it was not the Hungarian alphabetic system that derived from that of the Huns that later became Göktürk, nor the exact opposite. Basically, between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, in the Carpathian basin all these peoples came into contact, also creating military alliances and it was there that the cultural exchange I am talking about took place. From that cultural exchange, the Hungarians (therefore also those known over time as the Sicilians of Transylvania) created their alphabetical system, starting from the period of settlement in Pannonia, therefore during the seventh century; while the Huns brought this cultural '' gift '' to Mongolia following the collapse of their dominion over Europe at the death of their leader Attila, and right there during the eighth century. it allowed them to create the Orhon Valley alphabet: there are no Magyar inscriptions before the XNUMXth century, just as there are no Göktürk inscriptions before the XNUMXth century; however both peoples had contact with the Germanic peoples during the fifth century. Here's how the mystery is revealed. The Göktürk system is younger than the Hungarian one, and then both flourished when the relationships, or rather the cultural interfaces, had ended for centuries. There are two gap, two gaps to be filled: one diachronic, the other geographic. There is no shortage of scholars who have attributed the Mongol system now to the Pahlavi, now to the Sogdian, and then ascended to Aramaic. This system had its spread, being present on the monuments left by Tu-jue in China at the time of Tang dynasty; it was later used by the Uyghur Empire; and the variant called '' Yenisei '' is present starting from the XNUMXth century. in the lands of Kyrgyzstan, as well as in the Talas Valley in Turkestan. I do not accept the theory on the Avars as carriers of this graphemic system in Europe, spreading it among the Sicilian Magyars. Here too there are anachronisms. And what is even more important is that there is no grapheme-phoneme correspondence between the two alphabetic systems, although some graphemes are very similar (because both were learned from the Goths), however, they refer to different phonemes. But then, it must be said that the corpus of the inscriptions of the Orhon Valley includes a scanty documentation: two monuments erected in the aforementioned Valley between 732 and 735 of the Common Era, in honor of two gifts from the Kingdom of Gokturk, or the cippus erected for the prince Kul Tigin (cippus commonly known as '' obelisk '', dated 732) and the one erected for the Emperor Bilgä Qāghān (735); plus a few other inscriptions scattered around the area. The oldest is that of the cippus erected in 720 per Tonyuquq. I want to leave out what some scholars say about this epigraphic `` sector '', which I consider misleading. [1].

But then, who were these Göktürk? They were a people of Altaic origin, therefore Turks, mentioned in Chinese texts with the name of Let us know. This reign began in the second half of the sixth century. with the Khagan Bumin-Tuman and his sons in the territory previously occupied by the Huns (I cannot accurately say whether they were the true heirs of the Huns, the direct descendants or a people who, being vassal of the most ancient Huns, suffered only a great cultural influence, or even a people born from the fusion of the two elements); a kingdom that, like the Hun one, expanded rapidly towards the west, not finding much opposition among the sparse peoples of the steppes, many of whom at that time of Altaic lineage (there were no longer the fearsome Ary peoples of the steppes, Scythians and Sarmatians mainly, from which the Altaic peoples learned a lot from a cultural and spiritual point of view: shamanism, use of the horse, war tactics, etc.). Göktürk would mean '' Heavenly Turks '' or '' Numerous Turks '' and they were the first Altaic people to leave written texts, written with this alphabetical system. Their religion was shamanic Tengrism, very rich in Indo-Iranian elements (of those Indo-European peoples who inhabited the steppes, the direct descendants, together with Hindu and Medo-Persians, of the Culture of the Kurgan, and the latter, moreover Ural-Altaic lemma for '' mound '', precisely because this is how the current local populations call these Indo-European burial structures). The Khanates of this kingdom received various Christian (mainly Nestorian), Manichaean and Buddhist missionaries in their courts.

An important historical event to mention in order to better understand the origins of this alphabetical system is that of the rise to power of the first Khan of this kingdom, Bumin. In 546, Bumin Khan attacked the Tiele who rebelled against the Juan Juan, in turn allies of the Hephalites, the latter enemies of the Persian Indo-Europeans. At first, Bumin, by attacking the Tiele, wanted to get a princess of the Juan Juan in marriage, but they denied it to him. And so, Bumin finally decided to attack the Juan Juan, uniting his militias with those of the Kingdom of Wei, then dominant over northern China. In 552 he defeated the militias of the Kingdom of Juan Juan, under the command of the last Khan Yujiulü Anagui, thus becoming lord of those lands, marrying the princess of the Wei, Changle, and proclaiming himself `` King of kings '', Il-Qaghan, of the new Empire of the Göktürk with the capital city of Otuken. Subsequently, Bumin left the western part of the Kingdom to his brother Istami, who gave military support to the Persians to end the Kingdom of the Hephalites, the old allies of the Kingdom of Juan Juan. This war would have been the cause of the advance into European territory of the people of the Avars, who, according to what some scholars say, were the ones who brought these `` runic glyphs '' to Europe, spreading them among the Hungarians, that is still among the Magyar Sicilians. The problem is that here we are faced with a thousand aporias, not only from a chronological point of view, but also from a geographical and geopolitical point of view. But why precisely the Avars and also the Bulgars, those of Turanic lineage (the '' originals ''), never used this alphabetic system, or variants of it? The Kingdom of the Göktürk experienced a long period of bloody civil wars and divisions (Eastern Khaganate and Western Khaganate), supported first by the Chinese Sui dynasty and then by the Tang one. Precisely the eastern part, the one that kept the name Göktürk, throughout the seventh century. was vassal of the Chinese Empire of the Sui dynasty (the western one took the name Onoq `` Ten arrows ''), rebelling only once, when the Khan Hsien at the time of the transition from the Sui dynasty to the Tang dynasty between 626 and 630. But this attempt failed, because the famous Tiele, who at the time were now called Uyghurs (confederation of Tiele), loyal to the new Chinese Emperor Tang Taizong, rebelled in turn. And so, after Khan Hsien was captured, the eastern part became a Tang protectorate. In turn, the western part, after the assassination of the Khan of Onoq, Tung Sche-Hu, was divided into two kingdoms in conflict with each other, that of the Tulu and that of the Nushipi, and which were soon conquered in 657 by the Chinese militias. of the Tang dynasty. But always from the ashes of these two kingdoms of origin Göktürk emerged later in the East the Uyghurs, that is the descendants of the Tiele, and in the West the Turgesh, successors of the Onoq, that is the Turks that we all know, those who then converted to the 'Islam and occupied the Anatolian peninsula, today's Turkey. René Grousset traces a genealogical and migratory line that can shed more light on what has been exposed so far: in the XNUMXth century, the Oghuz, coming into conflict with the Uighurs for the domination of the Zhetysu region and suffering a defeat, moved towards the Caspian Sea ; they reached during the IX century. the Transoxiana region, on the western side of Turkestan, taking the place of the Peceneghi and the Kangarli along the Ural river, in the Emba region, forcing the latter to migrate north of the Black Sea or to join them; then settling in the tenth century. in today's Kazakhstan and from there reaching both southern Russia and the area occupied by the Bulgarians along the Volga (even before they settled in present-day Bulgaria, occupied by Slavic peoples). [2]. It is clear that these Oghuz are the descendants of the Onoq, called themselves Turgesh over time, then becoming (I quote now all the exo-ethnonymic variants): torks, Ghuzz, Gozz, Kuze, Oguz, Oguz, Ox, Oufoi, Ouz, Uguz, Uğuz, Uguz, Uz.

It seems right now to take a closer look at some of these peoples of Ural-Altaic origin, at least those who came to Europe and resided there among us. The Avari (non Avari) present themselves as an enigmatic people, the sources being very few on their account. It is in fact a `` theory '' (or rather only hypothesis) that this was a people of the Ural-Altaic language, closely related to those Bulgarians who, taking possession of what was once Thrace, would have reigned over the Slavs there present, thus giving the region its name, although the language remained Indo-European, precisely of the South Slavic (better to say Slavonic) lineage, still used today in comparisons. The Avars settled along the middle course of the Volga during the sixth century, making forays into Europe, even reaching Pannonia, after this area was left by the Lombards headed for Italy (we are in fact at the end of the sixth century. ). One thing is certain however, their vast European possession was named Khanate, and once stopped in their expansion by the Franco-Carolingian army, they settled between the Slavic and Magyar populations of the Finno-Ugric stock. For example, the name Attila turns out to be very common among modern Hungarians. About the fearsome Huns, it is known that they were a nomadic warrior people coming from the southern Siberian region and that during the fifth century. under the leadership of Attila he attacked the Western Roman Empire, forming a vast Eurasian Empire. In addition to the Chinese sources, those of the time of the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 was vulgar), which locate them in southern Siberia, we have the `` local '' ones, by the Syrian Greek speaker Ammiamo Marcellino, author of the res gestae, and of the Byzantine (of probable Gothic origin, it can be seen in the name, derivative of the Germanic theonym Soil) Giordane, author of The original Getarum and De summa temporum veligine actibusque gentis Romanorum, respectively of the IV and VI centuries. Ammianus informs us (Book XXXI, 2, 1) that the Huns came from the steppes, `` beyond the meotic swamps '': Hunorum gens monumentis veteribus leviter note ultra paludes Maeoticas glacialem oceanum accolens, ...

According to Chinese sources, after bitter struggles, these Xiong-Nu (stopped by the great wall), at the end of the first century. of the Common Era they migrated partly towards the West through the Ili Valley, settling along the course of the Volga, invading the territories occupied by the Indo-Iranian Alans and the Germanic Goths (Ostrogoths and Visigoths); the remainder remained under the political influence of the Han dynasty, north of China. But why did the Huns aim for Roman power? One of the many explanations, just think, come from China. I'll tell you briefly. Chinese sources, in fact, speak of a Hun kingdom comprising an area bounded by the Talas river course, the Altaj mountain complex and the course of the Tarim river. Once, in one of the many war campaigns waged by the Huns against the northern border of China (during 36 BC), the Chinese noticed a group of mercenaries in the service of the Huns fighting together `` like the scales of a fish ''. These were Roman legionaries, according to the Chinese, coming from the easternmost regions of the Parthian Kingdom. It is known that the Parthians took Roman legionaries prisoners following the defeat of Crassus at Carre in 53 BC and that of Marcus Anthony in 36 BC. given them a promise of freedom, namely the Huns. But the Chinese already knew the Romans. The Silk Road in fact put in communication West and East, only these '' relations '' would intensify a little after these events. However, some archaeologists disagree on this identification between Xiung-Hu and Huns, such as Otto Maenchen-Helfen and Christopher Kelly. According to the latter, the Huns would come from the steppes of Kazakhstan. According to Silvia Blason Scarel, the formation phase of the Huns, before overwhelming Alani and Goti, took place in the area between the Aral Sea and the Caspian Sea; these Huns would thus have circumvented the Caspian Sea to the north reaching to occupy an immense territory up to the Meotide swamp around the Sea of Azov, as the historian Ammiano Marcellino recalls in the res gestae (Book XXXI, 2) [3]. On the Huns we have Western testimonies that describe them as a typical people with a Mongolian physiognomy, although there are also descriptions that ascribe them to a Europid or at least Europoid phenotype, as if it were a polygenetic horde. But you know, in ancient times, it was quite easy to make certain confusions, especially if by '' Huns '' meant an army of very enterprising and ferocious knights. It is in fact very probable that within the militia of the Hun Kingdom there were also Indo-European and Finno-Ugric contingents, therefore with a Europid, that is, Nordic, in addition to the Europoid physiognomy. Procopius, another historian, in fact, speaks of Aparni, that is '' White Huns '', and the same Chinese sources speak of the Kian-Yun, the Khionites, or the '' Red Huns ''. Ammianus describes them at the end of the 2th century. (Book XXXI, 1, 11-XNUMX) in such a way [4], here is a summary: the people of the Huns overcome all barbarism limits, having in fact the habit of deeply furrowing the cheeks of newborns with the blade of a knife, so that the vigor of the beard at the time of growth was weakened due to the roughness of the scars, thus leaving beardless aging, without any beauty and eunuch-like; they have strong and firm limbs, a large neck and are strangely ugly and curved, to the point that they can be thought of as bipedal animals, similar to those roughly sculpted trunks that adorn the parapets of bridges; they are very crude in their standard of living, they do not feel the need for fire, nor for seasoning food, feeding only on roots of wild herbs and raw meat of any animal which they heat for some time between their thighs and the backs of their horses; they do not use to live in houses with roofs, but then abhor the use of a modest burial, and in fact among them there is no gable of reeds or a simple tent; they use to wander through hills and woods, accustomed since the cradle to endure snow, hunger and thirst, remaining indoors only for reasons of force majeure; therefore, they always go away, returning to the lodgings only in the greatest need, and in fact none of them feel safe under a roof; they use linen clothing or clothes made of mouse fur, nor do they have one robe for the house and another for going out; they fasten a faded tunic around their neck, without ever putting it down and therefore changing it so that it becomes too worn and it is not reduced to shreds; so they stay in the assemblies, discussing common interests; none of them works the land, none of them ever touch a plow, wandering without a fixed abode, without a law and a stable standard of living; like people on the run, they move with the carts, which are their only home, where their wives weave their horrible clothes and produce children, who stay with them until puberty; treacherous and unfriendly in the truces, they act immediately at every good opportunity and always on occasion cancel every good feeling with violent fury; they ignore, like unreasonable animals, good and evil, always being ambiguous and obscure in speaking; nor are they bound to respect for a religion or a form of worship, but they burn with great greed for gold; therefore, they are changeable of temperament and easy prey of anger, to the point that often in a single day, even without provocation, they betray their friends several times and then, even without the intervention of someone to appease them, they reconcile.

Thus far, Ammianus' testimony seems to refer precisely to the Mongols, both in the description of the phenotype and in the description of habits. But we must understand if this information is first of all true, first-hand. You know, a little skepticism never hurts. But here we know, what a scholar of the Roman ecumene perceived and understood about people coming from places totally alien to him comes into play. They were not in fact anthropologists, and it is therefore clear that they emphasized (at times too much) everything they could not feel as similar and presented as a threat, that is, a prejudice based on a possible and imminent danger. According to Christopher Kelly, in fact, here is the topos which contrasts the foreigner, the '' barbarian '', perceived as '' rough and uncivilized '' and the '' Roman civil and civilizing '', as all peoples outside the Roman border were considered '' inferior and without laws '', and also '' brutal, dishonest, without culture, without good government and religion '', just as Herodotus did towards the Scythians; therefore, according to Kelly, it is unlikely that Ammianus came into contact with the Huns, as the historian Priscus of Panion would have done in the fifth century, who visited Attila's court, giving a more positive and therefore reliable description. [5]. For example, Ammianus says that the Huns had their own chariots for home, while Priscus speaks of tents; Ammianus says that the Huns ate raw meat, when cauldrons used in cooking and attributable to this people are known in Archeology. Jordanes describes the Huns in his own The original Getarum in this way (book I, 24) [6]: “(1) After a short time, as Orosius tells us, the race of the Huns, more ferocious than the same ferocity, was unleashed against the Goths. From ancient traditions we learn that this was their origin: Philimer, king of the Goths, son of Gadaric the Great, who in turn was the fifth in the succession to hold dominion over the Goths after their departure from Scandinavia and that, as we have said , he entered the land of the Scythians with his people, he found among his people some witches, whom he himself called Haliurunnae in his native language. Suspecting these women, he expelled them from his people, forcing them to wander into exile, far from his entourage. (2) There, the impure spirits, who saw them wandering in the desert, gave themselves to them in intercourse generating this wild race that initially inhabited the swamps. A poor, disgusting and frail people, almost non-human and with a language that scarcely seemed human. This is the origin of the Huns who came to the lands of the Goths. (3) This people, as the historian Priscus tells us, settled on the farthest bank of the Meotic swamp. They loved hunting and showed no other skill in any art. After growing up as a nation, they began to disturb neighboring bloodlines with thefts and robberies. Once, while the hunters of their tribe were as usual looking for fun on the farthest edge of the Meotic swamp, a doe unexpectedly appeared at their sight entering the swamp, acting as a guide to the path, advancing and stopping several times. . (4) The hunters followed it, crossing the swamp on foot, which they had always considered as impracticable as the sea. And so the unknown land of Scythia revealed itself to them and the doe disappeared. Now, in my opinion, the evil spirits, from whom the Huns descended, did this out of envy of the Scythians. (5) And the Huns, who were previously unaware of the fact that there was another world beyond the Meotic swamp, were taken with admiration for the land of the Scythians. And being insightful, they believed that this path, absolutely unknown in the past, had been revealed to them by a Deity. They returned to their tribe and, by recounting what had happened to them and praising Scythia, they persuaded all the others to hurry to take the path they had found leading the doe. All those the Huns captured, once they entered Scythia, were sacrificed to their victory, all the others conquered and placed under their dominion. (6) Like a cyclone made up of several nations, they crossed the great swamp and immediately rushed on the Alpidzuri, the Alcidzuri, the Itimari, the Tuncarsi and the Boisci, which bordered on that part of Scythia. Even the Alans, who were their equal in battle, but unlike them more advanced in civilization, in manner and appearance, were exhausted by their incessant attacks and submitted to them. (7) This more from the great terror aroused by their appearance than by the fact perhaps of being superior in the battlefield, making their enemies flee with horror in front of their dark and frightening aspect; and, if I can define it that way, a sort of shapeless lump, not having a head at all and with holes for eyes. Their hardness is evident in their wild appearance, being cruel beings with their children from birth, as they use to cut the cheeks of males with the sword, so that before receiving milk for nourishment they learn to bear wounds. (8) Therefore they grow old without beard and young people are without beauty, because the face furrowed by the sword ruins with the scars that the natural beauty of the beard leaves. They are short in stature, quick in body movements, vigilant knights, with broad shoulders, ready to use bow and arrows, with a firm neck, always erect with pride. Although they live in human form, they possess the cruelty of wild beasts. (9) When the Goths saw this enterprising race that had invaded many nations, they were afraid and consulted their king in order to escape from such an enemy. Now, although the king of the Goths, Hermanaric, had been conqueror of many peoples, as we have just said, while he deliberated on the invasion of the Huns, the treacherous tribe of the Rosomons, who at that time were among those who owed him their tribute, took the opportunity to catch him off guard. When the king gave the order that a certain woman of the tribe I have mentioned, named Sunilda, be tied to the wild horses and torn to pieces by driving them at full speed in opposite directions (and this was wanted by the fury of her betrayed husband), his brothers, Sarus and Ammius, came to avenge their sister's death by planting a sword in Hermanarico's side. He, weakened by the blow, drew out his whole miserable existence in physical weakness. (10) Balamber, king of the Huns, took advantage of Hermanaric's state of health, moving an army to the land of the Ostrogoths, who had already separated from the Visigoths due to some dispute. Meanwhile, Hermanaric, who was no longer able to endure either the pain of his wound or the presence of the Huns, died at the great age of one hundred and ten.

Furthermore, again from Giordane's text other information can be deduced that refers to the life and deeds of the leader Attila. In summary: they got wounds on their cheeks as a sign of mourning for the bravest warriors, preferring to weep the heroes with the blood of men than with the tears of women; moreover, they practiced cranial deformation, lengthening the skull cap in imitation of the heads of dolichomorphic Indo-European peoples, or Scythians and Sarmatians, generally Indo-Iranians, from whom they borrowed many customs [7]. This practice, carried out in the tenderest childhood by tightening the head by means of a strong bandage, when the cranio-synostosis has not yet occurred, would have made one's head appear congenitally brachymorphic (typically turanic and mogolide) `` similar '' to the dolichomorphic ones of the elite Indo-Europeans of which the Huns themselves were fascinated, certainly showing a religious reverence. The Altaic peoples were the first to come into contact with the Kurgan ('' mounds ''), the tombs of the Scythian-Sarmatian populations, of Indo-Iranian stock. There they would see the bones and skulls and would understand that '' it was necessary to be like them '', imitating them also in their physical and physiognomic aspect, being able in this way to acquire '' their great strength and wisdom ''. Mongolian shamanism, as already mentioned, derives precisely from this Indo-European culture, as well as the copious use of the Swastika, especially the polar one, the Sauvastica (with arms turned to the left), still very widespread in Mongolia. Nothing remains of the language of the Huns, and the same anthroponyms, such as the best known of all, Attila, do not seem to be of Turkic origin at all. And here too there are those who favor a Finno-Ugric filiation, ascribing this language to a Proto-Hungarian dialect, or ascribing it to the Iranian languages. Once again, I can demonstrate just how wrong there is in these other theories.

In fact, I remind you that '' Attila '' was not a praenomen, but a surname, that is an epithet, a nickname, of Gothic origin among other things, therefore Germanic and not Altaic or of another lineage, meaning '' Little father '', which can be approached both at the semantic level and at the level of phonetic sequence (something even more important to trace its genealogy) to the Hellenic prename '' Attalus '' (in practice, its Hellenic correspondent). And so the names of his predecessors, uncle Rua and brother Bleda, must also be treated. An epithet originating from a well-known radical element: atta '' papa '' (Indo-European infantile term of endearment), to which the suffix was added to form the diminutive form in -l- (just like in Latin, where we have beard '' beard '', ursulus o ursula '' teddy bear '' and '' teddy bear '', etc.). So, strange to say, given the appointment that the character had at his time, flagellum dei, his nickname actually corresponds today to '' daddy ''. In the Anatolian peninsula we find (thanks to excursus evemeristici di Diodoro Siculo) in the myth Atta e Attis, lemma remained over time and then acquired by the Turks who arrived there during the Middle Ages in the form of ata; as we find it today widespread in central Europe thanks to the memories left by the Hun leader, as in the proper name of a Hungarian person Attila (in Hungarian father means '' father ''), as well as in forms Ethele, Eating ed South, the latter two feminine, all of German derivation, variants of the form Etzel, that is the onomastic form recurrent in the Nibelung song and referring precisely to the leader of the Huns. But then our Attila as he was really called? The real name would have been Avithohol, but having taken possession of the territory where the Goths were settled, he was called by the latter (perhaps in reference to the rather small stature compared to them, perhaps as a term of endearment towards the character) Attila '' Daddy ''. A comparison is easily found in the Gothic nickname Ulfilas '' Lupacchiotto ''.

Also the term to designate a king or a leader among the Altaic peoples, Khān (in the Mongolian writing system хан), is of Indo-European origin. It is also found in other forms in the Asian continent and which transliterated is rendered: blood, qaghan, qa'an, Kagan, khan. In the Altaic languages it refers precisely to '' great prince '' and '' monarch ''. A woman belonging to this rank was recognized with the headwords khanum o khanim. The semantic root is, as already said, frankly Indo-European, referable to the one it gave in the Germanic languages: Booking in Modern English (itself from Old English cyning/Tzingar/cyneg/cynig/cuning/kyning/yellow, from the Old Saxon yellow); King in Modern German (itself from Old High German yellow/khuninc); king in Norwegian Bokmål (directly from Norse konungr/kongr); in Icelandic konungur/kóngur (always from Old Norse forms); in Swedish conung/king (from konunger/kununger/kunger); all from the original Kuningaz; as well as in the Celtic that -Booking- (+ termination of the passive participle in t) which is found in high-sounding names such as that of Vercingetorix (Uerkingetorix). In Turkish, we have today bead, of unequivocal Slavic derivation (in Polish we have in fact King, in Macedonian bead, in Serbian to the king, in Croatian King, in Czech king, in Russian korol '), but in Mongolian still хaан, transliterated khan; and again in Hungarian King (therefore of Slavic derivation), in Estonian and Finnish king (directly from the original Germanic form); and finally, again in the Indo-European context, in Lithuanian we have king/the priest. And do not be surprised if in Japan, in this wonderful nation, '' king '' is said king, read by キ ン グ. These waves of spiritual, cultural and linguistic influence reached Japan, the noble nation of Emperors and Samurai, although not directly. For this reason the various Altaic groups, including the Huns (and these can always be ascribed to this lineage) used to modify their brachymorphic skulls from the earliest childhood, in order to condition the cranio-synostosis, thus imitating the skulls of the peoples' 'Gentlemen', those of the Kurgan, that is the Indo-Iranian peoples, from whom they have learned, among many things, horse riding (Culture of Srednij Stog, 4500-3500 BC). This word, Khān '' king '', used beyond the Uralic chain by non-Aryan populations, however, has an undoubted Aryan origin, and to be even more precise a Germanic origin: from * kunją `` patrilineal line / clan / family '' (in turn from the Proto-Indo-European ancestral root *goxnehx- '' generate '', hence the sequence gens/ γένος /kyn/Jana -जन- `` lineage / race '' in Latin / Ancient Greek / Norse / Sanskrit) + * -ingaz< * -ungō, genitival gerundive suffix for '' to belong '', therefore '' belonging to the clan / belonging to the patrilinear line ''. This is to make you understand something really important about linguistic analysis: you cannot improvise without following any method that has '' mathematical '' bases, without which, really any theory and consideration on linguistic origins and filiations risk becoming '' farraginose '' (although many are already a priori). For those who see origins from Pahlavi in the Göktürk inscriptions, it should be known that we are always talking about a form of writing used for Medo-Persian dialects, therefore Indo-European.

And to conclude with a flourish, if we take into consideration, for example, the grapheme of the Göktürk system indicating the front vowels, the open sound a and the semi-closed one e, we immediately realize that it presents a certain similarity, therefore a probable derivation, with the Gothic runic glyph Wear/Aihs ['' Sacrifice '' and '' Symbolic piece of wood detached from a yew branch representing the biunivocity between life and death ''; I remember that in the present text the names of the runic glyphs are in Gothic, ie Old East Germanic], which sounds like e closed and long (derived from the primitive diphthong ei, and which turned to the left becomes '' Ignition '', in Futhorc Friso-Anglo-Saxon Cweorð), in turn corresponding to the Sicilian-Magyar grapheme indicating the deaf velar occlusive k); so if I take the grapheme of the Göktürk system indicating the voiced dental occlusive d, we realize that it has a certain derivation from the Gothic runic glyph Gewa/Giba ['' Gift '' and '' Bond between the two exchanging parts ''], which in turn corresponds to the Sicilian-Magyar grapheme indicating the voiced bilabial occlusive b; and finally that the grapheme of the Asian system indicating the closed front vowel i (in turn laryngalization / vocalization of iodine) and the deaf bilabial stop p (if facing left), we further notice that it has a certain derivation from the Gothic glyph Laas/lagus ['' Fluidity of water '', '' What stimulates growth '', also '' Having control over the elements that surround us ''], and which once again corresponds to the Sicilian-Magyar grapheme indicating the palatal approximant sound j (facing left).

Note:

[1] György Kara, Aramaic Scripts for Altaic Languages, 1996; Orkun Hüseyin Namık, Ancient Turkish Inscriptions (trad. ''Ancient Turkish inscriptions''), Ankara 1994; M. Ergin, Orkhon Monuments (transl. The monuments of the Orkhon), İstanbul 1992; Tekin Talât, Orhon Yazıtları (transl. The Epigraphs of the Orkhon), Ankara 1988; YY. VV., Steppe Empires. From Attila to Ungern Khan (with preface by F. Cardini), Centro Studi Vox PopuliPergine 2008.

[2] R. Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, and. Rutgers University Press, New Jersey, USA 1991, p. 148 (book of 718 pages); and. I with the title L'Empire des steppes, Attila, Genghis-Khan, Tamerlan, Paris 1939.

[3] Silvia Blason Scarel, Attila and the Huns, and. L'Erma di Bretschneider, Rome 1995, pp. 16-17.

[4] Ammiano Marcellino, res gestae, book XXX, 2, 1-11: (1) Hunorum gens monumentis veteribus leviter note ultra paludes Maeoticas glacialem oceanum accolens, omnem modum feritatis excedit. (2) ubi quoniam ab ipsis nascendi primitiis infantum ferro sulcantur altius genae, ut pilorum vigor tempestivus emergens conrugatis cicatricibus hebetetur, senescunt imberbes absque ulla venustate, spadonibus similes, conpactis omnes firmisque member conmarginandis pontibus portrayed stipites dolantur incompte. (3) in hominum autem figure licet insuavi ita visi sunt asperi, ut neque igni neque gustatis indigeant cibis sed radicibus herbarum agrestium et semicruda cuiusvis pecoris carne vescantur, quam inter femora its equorumque terga subsertam fotu calefaciunt short. (4) aedificiis nullis umquam tecti sed haec velut ab usu communi discrete sepulcra declinant. nec enim apud eos vel arundine fastigatum reperiri tugurium potest. sed vagi montes peragrantes et silvas, pruinas famem sitimque perferre ab incunabulis adsuescunt. peregre tecta nisi adigente maxima necessitate non subeunt: nec enim apud eos securos existimant esse sub tectis… (5) indumentis operiuntur linteis vel ex pellibus silvestrium murum consarcinatis, nec alia illis domestica vestis est, alia forensis. sed semel obsolete coloris tunic collar insert non ante deponitur aut mutatur quam diuturna caries in pannulos defluxerit defrustata. (6) galeris incurvis capita tegunt, hirsuta crura coriis muniendis haedinis, eorumque calcei formulis nullis aptati vetant step gressibus liberis. qua causa ad pedestres parum adcommodati sunt pugnas, verum equis prope adfixi, duris quidem sed deformibus, et muliebriter isdem non numquam insidentes funguntur muneribus consuetis. ex ipsis quivis in hac natione pernox et perdius emit et vendit, cibumque sumit et potum, et inclinatus cervici angustae iumenti in altum soporem ad usque varietatem effunditur somniorum. (7) et deliberatione super rebus proposita seriis, hoc habitu omnes in commune consultant. aguntur autem nulla severitate gifts sed tumultuario primatum ductu contenti perrumpunt quicquid inciderit. (8) et pugnant non numquam lacessiti sed ineuntes proelia cuneatim variis vocibus sonantibus torvum. utque ad pernicitatem sunt leves et sudden, ita immediately deindustria dispersi vigescunt, et inconposita acie cum caede vast discurrunt, nec invadentes vallum nec castra inimica pilantes prae nimia rapiditate cernuntur. (9) eoque omnium acerrimos easy dixeris bellatores, quod procul missilibus telis, acutis ossibus pro spiculorum acumine arte mira coagmentatis, et distantia percursa comminus ferro sine sui respectu confligunt, hostisque, dum mucronum noxias memendi observant, contortis laciniis inligant resistors, ut laquiseat degrees facultatem. (10) nemo apud eos arat nec stivam aliquando contingit. omnes enim sine sedibus fixis, absque lare vel lege aut victu stable dispalantur, semper fugientium similes, cum carpentis, in quibus habitant: ubi conuges taetra illis vestimenta contexunt et coeunt cum maritis et pariunt et ad usque pubertatem nutriunt pueros. nullusque apud eos interrogatus respond, unde oritur, potest, alibi conceptus, natusque procul, et longius educatus. (11) for indutias treacherous inconstantes ad omnem auram incidentis spei novae perquam mobiles, totum furori incitatissimo tribuentes. inconsultorum animalium ritu, quid honestum inhonestumve sit penitus ignorantes, flexiloqui et obscuri, nullius religionis vel superstitionis reverentia aliquando untangled, auri cupidine inmensa flagrantes, adeo permutabiles et irasci faciles ut eodem aliquotiens die a sociis nullo it nullo nemiscantique propenique inritiid saepe.

[5] Priscus participated in a diplomatic mission to the king of the Huns, Attila, in the wake of the officer Maximin, his friend, between 448 and 449. What he wrote (in Greek) has been handed down to us with the title of History, and at present these are only fragments. The Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, reigning in the XNUMXth century, had the testimonies of the embassies sent by the Emperors to people, dividing them into two parts: Excerpta de legazionibus Romanorum ad gentes, that is '' Extracts of the embassies of the Romans to the peoples '', e Excerpta de legazionibus gentium ad Romanos, that is' 'Extracts from the peoples' embassies to the Romans''. Constantine VII himself gave it as a title History o Gothic history (at least so he quotes in his writings); but in the Suidas there is the quote Byzantine history e Events of Attila's time, and so is its writing in eight books. The fragments to be consulted are from n. 3 to 19.

[6] This is the title he gave to the writing Theodor Mommsen. Here is the text (Book XXIV, 24, 1-10): (1) Post autem non longi temporis interval, ut refert Orosius, Hunnorum gens omni ferocitate atrocior exarsit in Gothos. Nam hos, ut refert antiquitas, ita extitisse conperimus. Filimer rex Gothorum et Gadarici magni filius qui post egressu Scandzae insulae iam quinto loco tenens principatum Getarum, qui et terras Scythicas cum his people introisse superius a nobis dictum est, repperit in populo his quasdam magas mulieres, quas patrio sermon Haliurunnatque is ipse habens suspectas de medio sui proturbat longeque ab exercitu sua fugatas in solitudinem coegit errare. (2) Quas spiritus inmundi per herimum vagantes dum vidissent et eorum conplexibus in coitu miscuissent, genus hoc ferocissimum ediderunt, quae fuit primum inter paludes, minutum tetrum atque exile quasi hominum genus nec alia voce notum nisi quod humani sermonis imaginem adsignabat. Such igitur Hunni lineage created Gothorum finibus advenerunt. (3) Quorum natio saeva, ut Priscus istoricus refert, Meotida marsh further ripa insidens, venationi tantum nec alio labore experta, nisi quod, postquam crevisset in populis, fraudibus et rapinis vicinarum gentium quiete conturbans. Huius ergo gentis, ut adsolet, venatores, dum in interioris Meotidae ripam venationes inquirent, animadvertunt, quomodo ex inproviso cerva se illis optulit ingressaque paludem nunc progrediens nunc subsistens index viae se tribuit. (4) Quam secuti venatores paludem Meotidam, quem inpervium ut pelagus aestimant, pedibus transierunt. Mox quoque Scythica terra ignotis apparuit, cerva disparuit. Quod, credo, spiritus illi, unde progeniem trahunt, ad Scytharum envy id egerunt. (5) Illi vero, qui praeter Meotidam alium mundum esse paenitus ignorabant, admiratione ducti terrae Scythicae et, ut sunt sollertes, iter illud nullae ante aetati notissimum divinitus sibi ostensum rati, ad suos redeunt, rei gestum edocent, Scythiam laudant sua gente persuasa index dedicerant, ad Scythiam properant, et quantoscumque prius in ingressu Scytharum habuerunt, litavere victoriae, reliquos perdomitos subegerunt. (6) Nam mox ingentem illam paludem transierunt, ilico Alpidzuros, Alcildzuros, Itimaros, Tuncarsos et Boiscos, qui ripae istius Scythiae insedebant, almost quaedam turbo gentium rapuerunt. Halanos quoque pugna sibi pares, sed humanitate, victu formaque dissimiles, frequent certamine fatigantes, subiugaverunt. (7) Nam et quos bello forsitan minime superabant, vultus sui terror nimium pavorem ingerentes, terribilitate fugabant, eo quod erat eis species pavenda nigridinis et velud quaedam, si say fas est, informis offa, non facies, habensque magis puncta quam lumina. Quorum animi fiducia turvus prodet aspectus, qui etiam in pignora his first die born desaeviunt. Nam maribus iron genas secant, ut ante quam lactis nutrimenta percipiant, vulneris cogantur undergo tolerantiam. (8) Hinc inberbes senescunt et sine venustate efoebi sunt, quia facies ferro sulcata tempestivam pilorum gratiam cicatricis absumit. Exigui quidem forma, sed argutis motibus expediti et ad equitandum promptissimi, scapulis latis, et ad arcos sagittasque Parati firmis cervicibus et pride semper erecti. Hi vero sub hominum figure vivunt beluina saevitia. (9) Quod genus expeditissimum multarumque nationum grassatorem Getae ut viderunt, paviscunt, suoque cum rege deliberant, qualiter such se hoste subducant. Nam Hermanaricus, rex Gothorum, licet, ut superius retulimus, multarum gentium extiterat triumphator, de Hunnorum tamen adventu dum cogitat, Rosomonorum gens infida, quae tunc inter alias illi famulatum exhibebat, such eum nanciscitur occasion decipere. Dum enim quandam mulierem Sunilda nomine ex gente memorata pro husbands fraudulent discessu rex furore commotus equis ferocibus inligatam incitatisque cursibus for different divelli praecipisset, fratres eius Sarus et Ammius, germanae obitum vindicantes, Hermanarici latus ferro petierunt; quo vulnere saucius egram vitam corporis inbecillitate contraxit. (10) Quam adversam eius valitudinem captans Balamber rex Hunnorum in Ostrogotharum part movit procinctum, a quorum societate iam Vesegothae quadam inter se intentione seiuncti habebantur. Inter haec Hermanaricus tam vulneris pain quam etiam Hunnorum incursionibus non ferens grandevus et plenus dierum hundredth tenth year vitae suae defunctus est. Cuius mortis occasionio dedit Hunnis praevalere in Gothis illis, quos dixeramus oriental plaga sit et Ostrogothas nuncupari.

[7] C. Kelly, Attila and the fall of Rome, Milan 2009; P. Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History, Milan 2006.