Washington Irving knows the value of orality as a privileged means of preserving and handing down memory; his short stories have the rhapsodic trend, the polyphonic sonority typical of speech and the writer entrusts improvised storytellers with the task of reconnecting the scattered threads of a shared cultural identity, weaving, between one side of the Atlantic and the other, the warp and weft of an idem feel through their stories, in a dense network of references and quotations.

di Paul Mathlouthi

"America is not New York and Los Angeles, but everything in between." To dispense this rare pearl of wisdom, fulminating in its self-evident simplicity, it was not William Faulkner, nostalgic cantor of the Southern epic, nor Jack Kerouac or some other disheveled and dissolute enfant prodige of the Beat Generation, but – readers don't want me – Ned Flanders, animated character who in the successful series of Simpson embodies, albeit in decidedly non-rigorous and not at all evangelical stylistic features that are typical of Matt Groening's brilliant masterpiece, the way of thinking of the most intransigent and retroactive Calvinism which, in spite of the abused cliché ofAmerican way of life tolerant and inclusive at all costs so dear to the progressive and liberal culture of our house, it innervates itself the deep soul of the United States, flows, as William Carlos Williams would have said, in the very veins of the New World.

Not surprisingly in the first verses of the Songs, a cyclopean poem which, in the intentions of its tormented creator, was supposed to represent for the young nation that arose on the other side of the Atlantic theOmphalos, distilling in the minds and hearts of the descendants of the Pilgrim Fathers the incandescent matter of the primeval myth, Ezra Pound compares, in a sort of ideal symbolic continuity, the epic crossing of the May Flower to the epic of Ulysses:

On board we carried our bodies laden with tears

[1]

[...] Running with the wind in full sail until evening.

Off the sun, shadow on the ocean,

We came to the edge of the deep waters

[...] We came to the foretold place.

A journey that is the act of foundation par excellence, a place of the spirit even before being a historical event, which takes place under the banner of an incurable dichotomy, that between Salvation and Damnation. The spasmodic palingenetic anxiety that underlies the search for a new Promised Land in which to build the "city on the hill", the earthly epiphany of the heavenly Jerusalem, is accompanied in the preaching of the Quakers by the delirious ravings about the imminent and inevitable coming of the Apocalypse.

An ascetic religiosity, Manichaean and Puritan, strongly polarized on the theme ofatavistic clash between Light and Darkness in which the emphasis on purity, the only possible viaticum for entry into the Kingdom of Heaven to be achieved by means of an austere and blameless lifestyle bordering on self-flagellation, corresponds, in a perfect compensatory dialectic specularity, to a morbid obsession with very strong implications erotic for all that belongs to the sphere of the demonic. They are the fixed idea of carnal and expiatory violence curled up in the flesh and the archaic, inextinguishable sense of guilt of Old Testament ancestry about the bodies that are both coveted and forbidden, profaned and offered to the Devil to provide on the other hand, in the masterpiece of Arthur Miller, the main argument in support of the inquisitorial zeal of the judges assembled in Salem to try Abigail Williams and her unfortunate associates accused of witchcraft [2].

For those who, like the Pilgrim Fathers, believe unshakeably in the majesty of God and live in constant fear of his final judgement, Lucifer represents an irresistible pole of attraction, he is a traveling companion from which it would be impossible to separate as he symbolizes the transgression of ancestral rule and the conquest of a freedom otherwise denied. “Ego no te baptizo in nome Patris sed in nome Diaboli”thunders Captain Ahab dipping the harpoon with which he will pierce Moby Dick in Queequeg's blood, a prefiguration of the biblical Leviathan that haunts his mind: a terrible resolution pronounced by the hero of Herman Melville which, however, has all the ultimate and binding force of a real pact with a Faustian flavor.

America has built itself on such an elusive, elusive ambiguity towards the forces that lurk in the uncharted territories of the Shadow and whoever is not willing to take it into due consideration, attributing to it the value that is rightfully due to it, that is to say that of an archetype, runs the risk of not grasping the complexity of that in all its implications.American horror imagery between cinema and literature che da, Edgar Allan Poe a Thomas Ligotti, Via HP Lovecraft, Abraham Merritt, William Friedkin and Robert Eggers, has its roots in this contradiction and draws nourishment from it.

The innumerable immaterial entities that populate the mythological heritage of Old Europe, repudiated by the Pilgrim Fathers as an expression of a blasphemous paganism contrary to the rigid dictates of the magisterium of a monotheism that does not admit objections of any kind, come back transfigured in demonic guises to undermine the path of God-fearing children who go unaware into the forest of the world brandishing the torch of revealed Truth. Just what happens to Ichabod Crane, a character sprouted from the fervent and sinister imagination of washington irving (1783 - 1859) to whom Johnny Depp has lent the likeness in the famous albeit very free film adaptation of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, signed by Tim Burton in the last part of the century that has just ended [3].

With the ironic and apparently disengaged style that is congenial to him, the New York writer, undisputed though unrecognized master of American Gothic, in the pages of the popular story, back in our bookstores in a double edition prepared by the publisher Carmine Donzelli, hesitates to present us his improbable alter ego as a good man, respected and well-liked by all, rationalist, placidly harmless and perfectly inserted in the plastered and a little asphyxiated social dynamics of that industrious community of Dutch settlers settled along the banks of the Hudson where, in the wake of the War of Independence, he found hospitality and shelter in the guise of schoolmaster and singing teacher.

However, unwitting forerunner of Roger Chillingworth described by nathaniel hawthorne, granite guardian of the law that The Scarlet Letter we discover that the young tutor is actually a student of alchemy and occult sciences an insane passion for the writings of Cotton Mather, cultivated in great secrecy, sheltered from the apprehensive and often inopportune attentions of its fellow citizens. An eminent physician, in favor of the pioneering practice of smallpox inoculation at the time as a means of defeating the epidemic that was decimating the colonies of New England, the prolific seventeenth-century polemicist is known in Puritan America above all for his pamphlet entitled The wonders of the invisible world, as well as for the History of witchcraft in New England, sort of handbooks modeled on the treatises of demonology by European authors such as Jean Bodin, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, in which the diligent preacher intends to offer the ministers of religion a mapping of the infernal hierarchies useful to those who intend to lead a fight without quarter against the multiform wiles of the evil one.

The reading of these exorcist summaries, regarding the reliability of which Ichabod Crane seems to place the most absolute trust, far from proving to be a solid anchor of faith for him, they instill in his soul, evidently predisposed to do so, an oblique inclination for the powers of darkness that grows out of all proportion, fueled by the tales of old Dutch women which, gathered in front of the hearth in the long winter evenings, fill the darkness with “fantastic stories of ghosts and evil spirits, of haunted fields and streams, of bridges and bewitched houses” [4]. The terrifying apparitions chase each other from mouth to mouth enriched with increasingly gory details, but within the reassuring walls of the opulent mansion of the Van Tassels where the unfortunate teacher is a guest, all the locals seem to share the opinion according to which

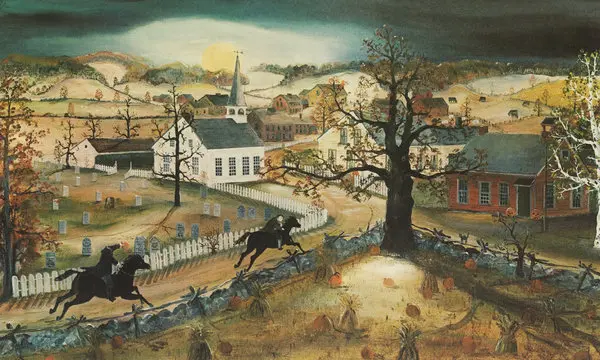

the ruling spirit who haunts this enchanted region, and who seems to be in charge of all the powers of the air, is a headless horseman. It is said that he is the ghost of a Hessian soldier, beheaded by a cannonball in an anonymous battle during the War of Independence, and that every now and then the peasants see him riding in the dark, as if he were flying on the wings of the wind. In fact, some of the most reliable historians maintain [...] that the body of the knight is buried in the church cemetery and that he rides to the place of battle in search of his head; the crazy speed at which he sometimes crosses the valley, like a night storm, would be due to the fact that he is late and in a hurry to get back to the cemetery before sunrise.

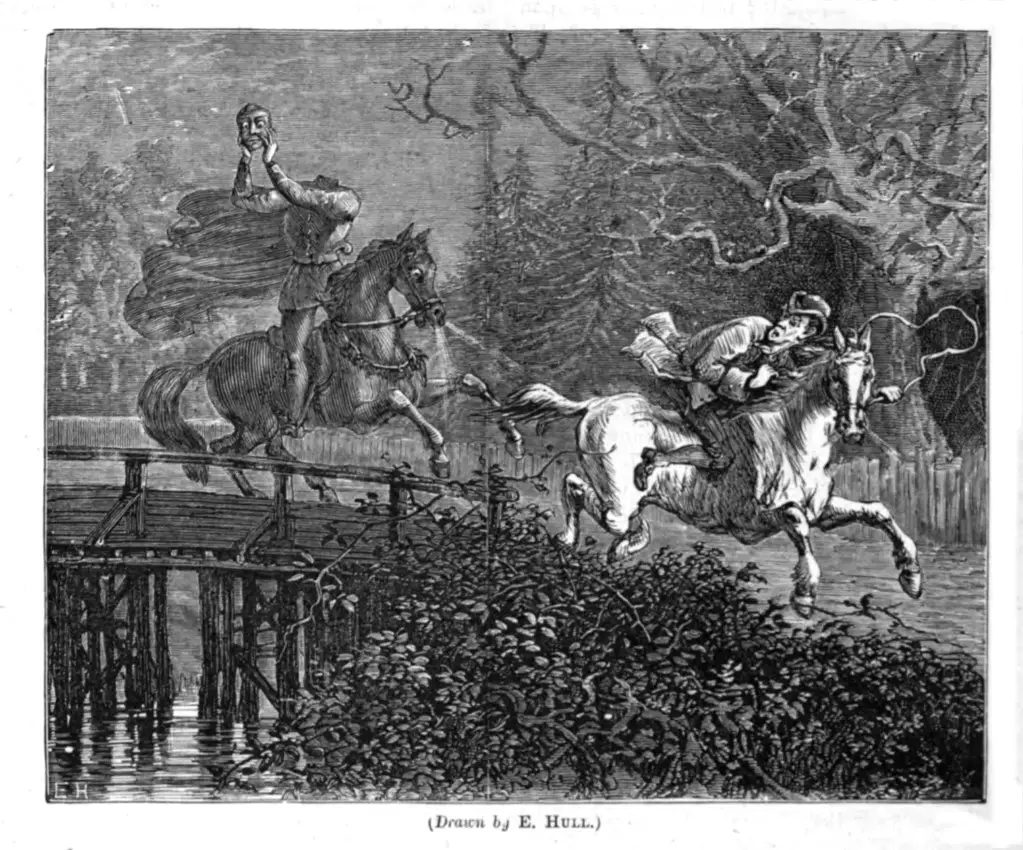

[5]

Old Brower swears he saw it disappear with a leap over the tops of the trees after taking the chilling form of a skeleton, while that braggart of Brom Bones, to strut in the eyes of the landlord's pretty daughter, Katrina Van Tassel, declares before the amazed present that he has challenged the specter in a breakneck race through the forest on his Daredevil. He would have even managed to beat him, he assures in an unbearable excess of drunken bragging, if suddenly the ghost hadn't vanished, wrapped in a tongue of fire! As for our incredulous Ichabod Crane, his remaining Enlightenment certainties are swept away in one fell swoop by the sudden appearance of the infamous knight who one night blocks his path on the way back home.

In the gloomy shadow, at the edge of the stream, he glimpsed something huge, shapeless, black and towering that didn't move but seemed to be crouched in the darkness, like a gigantic monster ready to pounce on the traveler [...]. Just then the indistinct cause of his terror moved, and with one leap he was in the center of the street. [...] Although the night was dark, the silhouette of the stranger was now somehow more visible: it was a powerful knight riding a large and powerful black horse. He showed no signs of hostility, but limited himself to remaining on the sidelines [...]. There was something mysterious and terrifying in the grim and stubborn silence of that stubborn companion, and he soon he discovered the reason. As he climbed a hillock, the figure of the knight stood out against the sky, gigantic and wrapped in a cloak: what was not Ichabod's horror in seeing that he was headless! And the horror grew even more when he realized that the head, which should have been in place of him on the neck, was instead resting on the pommel of the stranger's saddle! [...] Then they began to gallop side by side, and with each jump stones and sparks flew.

[6]

After that night, no one would see Ichabod Crane again from the parts of Sleepy Hollow, even if the wives gathered in permanent session would be ready to bet that the knight dragged the unfortunate master with him to Hell.

The analogies that link the spectral figure evoked by Washington Irving to the leader who in Nordic legends leads the procession of the damned Wild Hunt they are all too obvious and familiar to readers to dwell on in detail. Yet someone, no doubt more accredited than the author of this short note, wrote that the headless horseman would represent a metaphor for America's revolutionary demands, plastic projection of a society of equals, democratic and anti-hierarchical, epiphany of a headless state because it has no sovereign, therefore devoid of a "centre" in the sense evolian of this term. An up-to-date reading key that is not without interest and worthy of being explored elsewhere which, however, risks, in my humble opinion, making us lose sight of the symbolic and meaningful horizon within which the fil noir that unites one another unfolds the gothic tales of the American writer.

More than an intention of a political-ideological nature, at the roots of Irvinghian poetics it would be more appropriate to recognize a scruple that we could define as of a metahistorical if not spiritual nature, close to that which Oswald spengler would define the "Morphology of Civilization". Exactly like Ezra Pound, Washington Irving experiences the tear from Europe and its millenary tradition that we have seen to be at the origin of American mythopoeia in a problematic way, as an absence rather than a conquest, a pneumatic vacuum which in his opinion it is absolutely necessary to fill for America to truly find itself. Not having, unlike his more illustrious countryman, familiarity with the sense of the tragic, the New York writer declines this excruciating nostalgia for his origins according to the parameters of a colloquial and anti-rhetorical linguistic register, more akin to the narrative ways and tempos of the brothers' fairy tales Grimm his peers or the tales of ETA Hoffmann read during the long stay in Dresden that the abysmal depths of John Milton e William Blake, undisputed tutelary deities of the Puritan literary canon.

Washington Irving knows the value of orality as a privileged means of preserving and handing down memory; his short stories have the rhapsodic trend, the polyphonic sonority typical of speech and the writer entrusts improvised storytellers like Diedrich Knickerbocker with the task of to tie together the scattered threads of a shared cultural identity, weaving, between one side of the Atlantic and the other, the warp and weft of an idem feeling through their stories, in a dense network of references and quotations.

So if the Tom Walker to whom the Devil, dressed in improbable Indian clothes, reveals the location of the treasure buried by the pirate Robert Kidd closely resembles Peter Schlemihl, protagonist of the story of the same name by Adelbert von Chamisso who sells his shadow to the Tempter in exchange for a purse of gold coins, behind the alchemist Felix Velasquez, tried in Granada by the Holy Inquisition, it is not strange to suppose that the truth is concealed, placed in another time and another place by means of literary fiction, a really existed character, George Stirk, who, having arrived in Boston from his native Bermuda in 1639 to study medicine, became friends with John Winthorp Junior, son of one of the founders of the Massachusetts colony, who opened the doors of his esoteric library to him and begins the study of arcane mundi. She is certainly known to Washington Irving and, moreover, destined for great literary fortune given that, as the late wrote George Galli, even Lovecraft was inspired by him to give a face to Joseph Curwen, a dark occultist who makes his appearance in the novel The case of Charles Dexter Ward [7].

Ironically, in building the refined architecture of this interlocking game, the New York writer ends up offering, according to a perfectly circular trend, a first-rate exegetical weapon in support of that Puritan ethic from which he also seems willing to amend . The revelation of the existence of the invisible world in his time conjured by Cotton Mather, with his mind-boggling wonders, and a certain smug inclination towards the forces of Darkness which are ultimately the very particular figure of his narration, they become a warning addressed to the community of believers, they serve to confirm the need for another revelation, the divine one. Evidently not even a great writer like Washington Irving is allowed the luxury of escaping himself.

NOTE:

[1] Ezra Pound, The Cantos, I, vv. 4 – 11

[2] See Arthur Miller, The melting potin Theater, Einaudi, Turin 1965; p. 303 – 452. Of this famous drama in four acts, performed for the first time in New York on the evening of 22 January 1953 and translated into Italian by none other than Luchino Visconti, there are two well-known film adaptations. The first, titled The Virgins of Salem, was released in theaters in 1957 under the direction of Raymond Rouleau and boasts a screenplay by Jean Paul Sartre. The second, directed in 1996 by the Englishman Nicholas Hytner on an adaptation written by Miller himself, is entitled The Seduction of Evil and stars Winona Ryder as the main defendant. As for the bibliographic references, very useful for understanding the cultural context and the climate of growing psychological pressure that made the celebration of the Salem witch trials possible, remains the fundamental essay by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, The demon-possessed city. Salem and the social origins of a witch hunt, Einaudi, Turin, 1986. Finally, the brief but very punctual writing by Elio Vittorini, deserves to be mentioned, especially as regards the essentially theocratic character of Puritan religiosity, The fierce priests, included in his Diary in public, Bompiani, Milan, 2016.

[3] It must be said that, with the exception of the figure of the headless horseman, the rereading prepared by Tim Burton, however enjoyable, has little or nothing to do with the famous story by Washington Irving. Not only have the needs dictated by the cinematographic times led the screenwriters to expand the plot beyond measure, adding typical situations of the horror genre completely unrelated to the original text but, even more unbecoming, in the film the character of Ichabod Crane is misrepresented because, unlike his literary equivalent, he absolutely does not believe in the supernatural and indeed embodies the stereotype of the skeptical Enlightenmentist who relies only on the reliability of scientific data. An even worse fate, however, is the one our hero meets in the television series made in 2013 by a well-known American broadcaster, where he miraculously resurrects himself and finds himself catapulted into the twenty-first century! If it is true that one can die of too much philology, I am afraid however that in this case the mark has really been overstepped.

[4] Washington Irving, The Legend of Sleepy Hollowin fantastic tales, Donzelli, Rome, 2009; p. 73. There is also a single volume edition of this story, published by the same publisher, enriched by the beautiful illustrations by Arthur Rackam.

[5] Ibidem; page 67

[6] Ibid; p. 96 – 97

[7] Giorgio Galli, A collected tradition? in AA.VV, Finding Mary Frankenstein, International Graphics Center, Venice, 1994

.