Starting with the representation of Genesis XXII housed in the Beth Alpha Synagogue, we will analyze how the Book of Jubilees sanctioned a correspondence between the biblical passages of the Sacrifice of Isaac and the Liberation from Egypt. Furthermore, in the figure of Isaac, who appears here in the form of a helpless and frightened child, we will be able to observe the interpretative gap between the mosaic and the exegetical tradition. In numerous texts, in fact, it is the patriarch himself, now an adult and aware, who offers himself spontaneously to the divine plan.

di Lorenzo Orazi

COVER: CARAVAGGIO, SACRIFICE OF ISAAC, 1598

FOLLOWS FROM PART I

Beth Alpha

The synagogue of Beth Alpha was found in southern Galilee in 1929. The inscriptions, identified inside, certify that the structure belongs to the time of the empire of Justin I (518-527). From the entrance to the synagogue, three scenes unfold towards the wall that houses the Ark of the Torah, oriented towards Jerusalem. They represent the Akedah, the Zodiac and the Ark.

Let's consider our episode. Compared to the depiction of the same theme in Dura Europos, it is possible to note how here the artist adhered more strictly to the biblical narration: in the first place, the two servants with the donkey were added; moreover, the compositional development of the image from left to right is capable of suggesting the chronological linearity of the event, as reported by the sacred text.

On the left one of Abraham's servants rests his hands on the back of the donkey; the second holds the halter in one hand and a riding crop in the other. At the center of the image, a large ram standing in a vertical position is tied to a plant, disproportionate and small compared to the animal, which divides the sacred space from the profane one. Above the ram appears the Hand of God: it emerges, in a characteristic shape, from a sort of black cloud. We have come to the core of the scene. Abraham is represented with a beard and dressed in a tunic: in his right hand he holds a long dagger, while the left stretches out in a particularly ambiguous position: it is not clear whether he is placing Isaac on the altar or if, on the contrary, having already heard the Voice of God, prepare to draw him back to you. The figure of Isaac is perhaps the most enigmatic of the composition: we see a child suspended in mid-air, his arms are crossed but not tied; he is dressed in a tunic and wears a "strange scarf" around his neck; he is in the grip of an emotion of explicit terror.

Aries and Easter meaning

Similarly to what happened in the Dura Europos painting, here too the ram has been accorded considerable prominence. The animal does not appear, as reported in the biblical text, "with its horns entangled in a bush" (v.13); instead it is tied by the halter to a tree. This configuration seems to refer to the rabbinic tradition: it stated that the ram was originally created, on the eve of the first Saturday, in view of the role it was supposed to play in the Akedah [1].

In the Midrash the ram enjoyed wide consideration from the beginning. This attention is due to the fact that, if God had not provided him as a replacement for Abraham's son, the patriarch would never have had offspring and the fulfillment of the covenant would have been impracticable. Isaac's death would have sanctioned the failure of the promise; consequently, his liberation by means of the ram coincides with the liberation of Israel.

At the basis of this interpretative tradition we find the Book of Jubilees. Dated approximately between 160 and 150 BC, it is generally considered the first text of post-biblical literature to devote particular attention to the episode of Genesis XXII. In passage of the text concerning the Akedah we can observe a precise desire to build a link with the episode of the Liberation from Egypt, if not even to make the first a model for the second.

It is no coincidence that the Book of Jubilees reports a very punctual chronological structure: Abraham and Isaac leave for the sacrificial site on the twelfth day of the month of Nissan. Adding to this date three days of walking, which father and son take to reach the mountain, we would find ourselves on the fifteenth day of the month: it is the date on which the beginning of Pesach, the Jewish Passover, falls. Furthermore, at the end of the narrative, the text states that Abraham, to celebrate the salvation granted to his son, establishes a week-long holiday, and that he will continue to celebrate it in the years to come. It should be noted that both instances, both the chronological and the festive, are completely absent in the biblical original.

LA Huizenga in the article “The battle for Isaac: exploring the composition and function of the Aqedah in the Book of Jubilees” [2] identifies further internal connections, mainly of a linguistic nature, between the passage of the Akedah and that of the Liberation from Egypt. The Book of Jubilees states that Abraham, following the events of Genesis XXII, celebrates with "joy". The same term is used in the regulations regarding Easter: even liberation from slavery must be celebrated with "joy". Another point in common consists in the identification of the angel Mastema with the character of Satan. Mastema presides over both episodes: specifically, in the passage from the Akedah, he accuses Abraham of iniquity so that the Lord may test him. According to Huizenga, also in this case it is a textual comparison that provides the most decisive clues. In both narrations the verbs “shame” and “stood” appear: they refer respectively to Mastema and to the Angel of the Presence, and indicate the defeat of the former and the triumph of the latter. It should be emphasized that such a specific agreement of terms does not occur anywhere else in the text.

Both in the narration of the Akedah and in that of Easter it is therefore the demonic threat and the endangerment of the covenant that looms over the chosen people. Both redemptions take place by means of a substitution sacrifice: in the first case of the ram, in the second of the lamb. If Abraham had sacrificed Isaac, the seed would never have existed; if the Egyptian army succeeded in destroying Israel the covenant people would be extinct. Abraham's obedience on Mount Moriah thus prefigures that of the chosen people in Egypt. The textual, conceptual and chronological concomitance - concludes Huizenga - are not the result of chance, but necessary to establish a hermeneutical link between the two episodes.

The legacy of the Book of Jubilees will be welcomed in the celebrations of Pesach, to the point that on the eve night it became customary to narrate the story of the Sacrifice of Isaac. This association will be lost over time, probably due to the new meaning that Christianity will attribute to Easter as the death and resurrection of Christ [3]. The rabbinic tradition sees Genesis 22, 1-18 in the interpretative framework of the test of faith; the passage offers the image of the perfect sacrifice, in which the body of the ram and that of Isaac are made to coincide in a single whole. The situation changes in the reading of the church fathers, in which the devaluation of Isaac takes the upper hand; the latter is not the forerunner of Christ, but the ram itself:

“On behalf of Isaac the righteous, a ram appeared for the slaying, that Isaac might be released. The killing of the ram freed Isaac, so the killing of the Lord saved us all."

[4]

Both Isaac and the ram will be interpreted according to the method of typological reading as prefigurations of Christ; in some cases, however, the patriarch will be considered imperfect, and the time not yet ripe for sacrifice. The expiatory effect, which was so exalted in the rabbinical writings and in the Book of Jubilees, will not obtain the same success among Christians.

The submission of Isaac: Pseudo Philo

For the purposes of an adequate reading of the image of Genesis 22, 1-18 present in Beth Alpha, the figure of Isaac constitutes a central critical node. He is shown to us as a helpless and frightened child, helpless in the face of his father's choices. This constitutes a strong departure from the texts of the exegetical tradition: numerous writings, in fact, affirm that when Isaac was led to the sacrifice he was already an adult man. Such attention to Isaac's age is fundamental, as it expresses the need to think of him as mature enough to submit spontaneously to God's will. In the first century AD, this interpretative direction achieved wide success.

In the work "Liber antiquitatum Biblicarum", attributed to Pseudo Philo, the Akedah is referred to at three different times. Among these, the first fits into the narration of the story of Balaam, the soothsayer to whom Balak, king of Moab, asked to curse the people of Israel to counter their advance. God appears to Balaam and commands him to deny his services to the ruler, giving the reasons for the election of the people of Israel:

“Was it not concerning this people that I spoke to Abraham in a vision, saying, 'Your seed will be like the stars of the heaven', when I lifted him above the firmament and showed him the arrangements of all the stars? I demanded his son di lui as a burnt offering and he brought him to be placed on the altar. But I gave him back to his father and, because he did not object, his offering was acceptable before me, and in return for his blood I chose them."

(18.5)

Huizenga [5] underlines that in the passage the Akedah is considered valid in the eyes of God by virtue of Isaac's obedience. According to the author, in fact, the phrase "he did not object" must refer to Isaac: this causes a notable exaltation of his role in the story. If in the passage just quoted the theme of Isaac's condescension still remains implicit, continuing in the text we will see how Pseudo-Philo leaves no doubts about it open. Let us therefore consider the passage concerning the Canticle of Deborah, in which Abraham communicates to his son that he is about to be offered in sacrifice, and that his destiny is to return into the hands of the Lord. To his father's confession Isaac replies:

“Hear me, father. If a lamb of the flock is accepted for an offering to the Lord for an odor of sweetness, and if for the iniquities of men sheep are appointed to the slaughter, but man is set to inherit the world, how then sayest thou now unto me : come and inherit a life secure, and a time that cannot be measured ? What and if I hadn't been born in the world to be offered a sacrifice unto him that made me? And it shall be my blessedness beyond all men, for there shall be no other such thing; and in me shall the generations be instructed, and by me the peoples shall understand that the Lord hath accounted the soul of a man worthy to be a sacrifice unto him.”

[6]

To be considered worthy of sacrifice is an incomparable honor for Isaac; through his submission blessing will fall upon future generations, and through him instructions will be given to follow the divine will.

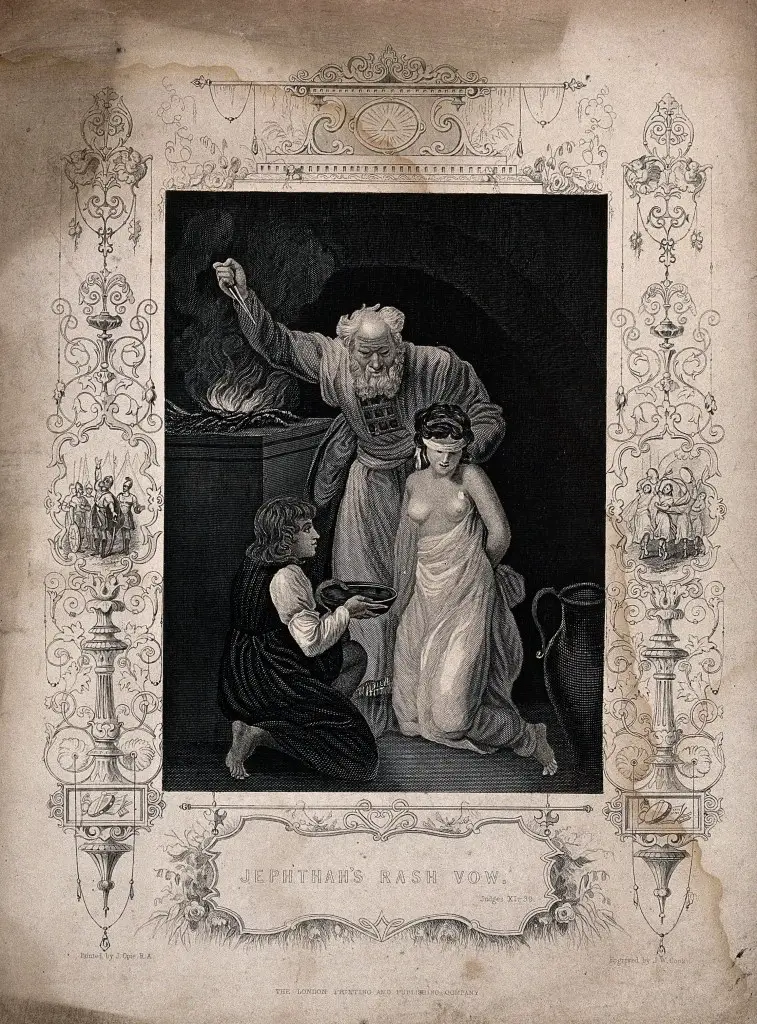

For the purposes of our study, one last passage from the LAB remains to be taken into consideration, the one which tells of the sacrifice of Seila, daughter of Jephthah. In the Bible, the episode is reported in the Book of Judges: Jephthah, before waging war against the Ammonite people, oppressors of the Israelites, vows to offer as a sacrifice the first one who would meet him upon returning from the war campaign. When he saw the profile of his only daughter, Seila, outlined on the horizon, Jephthah's face paled.

Pseudo Filone here compares the figure of Seila to that of Isaac, and Huizenga [7] he undertakes the task of identifying the literary affinities that unite the two characters. Seila is described as the fruit of Jephthah's belly (39.11), the same goes for Isaac, the fruit of Abraham's belly (32.2); the birthright of both is repeatedly extolled (39.11) (40.1). Above all other correspondence, the answer with which Seila welcomes the news of her sacrifice that awaits her stands out, it is this that illuminates her as a perfect analogue of Isaac:

“Who is there who would be sad to die, seeing the people freed? Or have you forgotten what happened in the days of our fathers when the father placed the son as a burnt offering, and he did not dispute him but gladly gave consent to him, and the one being offered was ready and the one who was offering was rejoicing?… If I will not offer myself willingly for sacrifice, I fear that my death would not be acceptable and I would lose my life for no purpose.”

(40.2, 3b)

Seila sees the memory of Isaac revive in her memory. It is the exemplarity of the latter, sanctioned in the Canticle of Deborah, that offers her the model of conduct in voluntarily giving herself to God so that his death does not happen in vain.

The Fourth Book of Maccabees

The elevation of Isaac to a model of conduct can also be identified in another text of the first century AD, namely the IV Book of Maccabees [8]. It is an apocryphal writing from the Old Testament, in which the idea of the predominance of religious reasons over emotions and passions is elaborated. The text tells the story of Eleazar and the seven brothers. Jason reigns over the people of Israel but his conduct is contrary to divine law, to the point that he decides to cancel the celebrations in the Temple. God's anger takes shape in the figure of Antiochus, who invades Jerusalem and orders the killing of anyone found in conformity with Jewish law. The entire narrative, concerning the martyrs Eleazar and the seven brothers who meet their fate, is structured on the example of Genesis XXII. Their tortures are defined as "trials" (1.7; 16.2) and, in reference to the protagonists, the author uses the epithet of "sons of Abraham" (6.17; 6.22; 18.23). Specifically, the mother of the seven brothers is described as follows:

“But this daughter of Abraham remembered his holy fortitude. O holy mother of a nation avenger of the law, and defender of religion, and prime bearer in the battle of the affections!”

(15-28)

Like her offspring and Eleazar, the woman too is "daughter of Abraham"; but she is given the further definition of "mother of the nations", derived from that of "father of the nations" of Abraham himself. Finally, the seven brothers, close to torture, encourage each other by making direct reference to Isaac:

“And one said, “Courage, brother”; and another, “Nobly endure”. And another, “Remember of what stock you are; and by the hand of our father Isaac endured to be slain for the sake of piety”. And one and all, looking on each other serene and confident, said, "Let us sacrifice with all our heart our souls to God who gave them, and employ our bodies for the keeping of the law."

(13-11)

At this date Isaac is already the archetype of the martyr. The fact that he is not sacrificed is irrelevant, what matters is the example of his firm obedience to the divine will. As already happened in the episode of Seila narrated by Pseudo Filone, the author of the IV Book of Maccabees argues that the death of the righteous has a redemptive effect on the people of Israel, driving away the oppressor and purifies from sins [9]. The suffering, the death of Eleazar and the seven brothers frees the people of Israel from the divine wrath, unleashed due to Jason's apostasy. The martyrs could have hidden their faith and embraced the pagan life desired by Antiochus, but they decide to entrust themselves to the divine plan. Their perseverance amazes the tormentors, to the point that the leader of the enemy troops points them out to the soldiers as models of courage. The invader, realizing that he has failed to convert the Israelites to paganism, abandons the land of Jerusalem.

Flavius Josephus

Finally, we must dwell on the Jewish Antiquities of Flavius Josephus. In the text "Josephus as a biblical interpreter: the Aqedah" [10], Feldman draws the reader's attention to the debt contracted by Flavius Josephus towards the Greek tradition. The examination starts from the statements of the philologist and literary critic Eric Auerbach. According to the latter, the Bible is characterized by an extremely sober narration, where only the phenomena necessary for the story to unfold are manifested, while the whole apparatus of thoughts and emotions remains in dim light, suggested only by silence or in fragmentary speeches.

Auerbach then compares the Homeric work with the Bible. If the first has a transparency that leaves little to the interpretation of the reader, the second, through the constant references to the past and the experiences of the characters, gives the story a strong component of suspense. Following the observations of the literary critic, Feldman believes that Josephus is Hellenizing the Biblical narrative. The elimination of suspense is, in this regard, a key point: Flavius Josephus obtains it by clarifying from the outset that the order to sacrifice Isaac is nothing more than a test, and further establishing that Abraham has already achieved happiness through the gifts of God, obtained as a reward for his constant obedience. Flavius Josephus omits God's order (Gen 22,2) and the dialogue between father and son (Gen 22, 7-8) in order to place the event in a rational and uniform distance.

In addition to the influence of Homer's work, Feldman identifies a closeness between the passage of Genesis XXII, as it is exposed in the Antiquities of the Jews, and Euripides' "Iphigenia in Aulis" [11]; reference work, as regards the themes of sacrifice and martyrdom, in the whole Greco-Roman tradition. In this regard, we can observe how Flavio Giuseppe emphasizes the silence that Abraham adopts regarding the order received from God, a silence that leads him to hide his plan even from Sarah, his wife. In Iphigenia the same happened between Agamemnon and Clytemnestra: the leader of the Achaeans writes a letter to her wife asking that Iphigenia be sent to him and, to justify her request, he claims that he wants to marry her off to Achilles. Both Abraham and Agamemnon take a vow of silence in order to prevent the divine will from being hindered.

Continuing with Flavius Josephus' review of Genesis XXII, we note that, as happened in the sources analyzed previously, Isaac is described as enthusiastic about embracing the destiny of sacrificial victim. His determination is such as to cause him to exclaim that, where he defies God's order, he is not worthy to be born:

“Now Isaac was of such a generous disposition as became the son of such a father, and was pleased with this discourse; and he said that he was not worthy to be born at first, if he should reject the determination of God and of his father, and should not resign himself up readily to both their pleasures; since it would have been unjust if he had not obeyed, even if his father alone had so resolved. ”

[12]

Iphigenia, for her part, replied in a very similar way: "If Artemis demands me, I, a poor mortal, will I oppose a goddess?". By virtue of this relationship between the two figures, Flavius Josephus' desire to provide the reader with Isaac's age acquires considerable importance. The author states that Isaac, at the time of the sacrifice, had completed his twenty-fifth year of age. According to Feldman, this clarification is due to the purpose of exalting the awareness with which Isaac submits to the divine will [13].

To understand the value of Flavius Josephus' observation it should be remembered that Iphigenia, in Euripides' text, is a young woman who has just reached the age necessary to marry (no later than thirteen or fourteen years), therefore implicitly considered as an unwitting victim. The Isaac of Flavius Josephus, on the contrary, is a man in the prime of his faculties, aware of the importance of his own destiny, Feldman argues that, providing the detail of age, Flavius Josephus uses a device capable of diminishing the horror that the episode could have aroused in the reader, and thus prevents any criticisms - just think of the one elaborated by Lucretius in his reading of Iphigenia [14].

In the passage from Jewish Antiquities which tells the story of Seila's sacrifice [15], the author does not adopt the same shrewdness. Flavius Josephus argues that Jephthah made the vow rashly, without adequately weighing the consequences. Faced with such imprudence, the Roman historian shows that he is not interested in alleviating the cruelty of the event. He first he condemns Jephthah's conduct explicitly; therefore, in a more implicit way, not bothering to give indications about Seila's age, he delivers her into the hands of the reader as a helpless girl.

To fully understand the value attributed by Flavius Josephus to the obedience of the patriarchs, we will dwell on one last point - which, moreover, determines a noteworthy deviation from the biblical text. In Gen. 22,9 Abraham, before placing Isaac on the altar, on firewood, binds him; Flavius Josephus omits this detail. Instead, Abraham gives his son a sermon explaining the reasons for the sacrifice. The discourse is purified of any sentimental accent, it rests on a structure of rigid logical concatenations.

To understand the importance of this omission it is enough to remember that the passage in which Isaac is bound is the one to which the rabbis refer to identify Genesis 22, 1-18: the title of "Akedat Yitzhak" literally means "binding of Isaac ”. For the rabbis even a patriarch is human enough to tremble at a knife that threatens death; great was therefore the concern that an attempt to free himself by Isaac could have made the sacrifice unwelcome to God. This is not the case for Flavius Josephus who, engaged in the attempt to make the faith of the biblical heroes magnificent, considers a tenacious moral firmer than any physical "ligature".

NOTE:

[1] Gutmann J., The Illustrated Midrash in the Dura Synagogue Paintings: A New Dimension for the Study of Judaism; Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 50 (1983), pp. 91-104; American Academy for Jewish Research, New York.

[2] Huizenga LA, The Battle for Isaac: exploring the composition and the function of the Akedah in the Book of Jubilees, The Continuum Publishing Group Ltd 2003, London.

[3] Gutmann J. (1987) The Sacrifice of Isaac in Medieval Jewish Art; Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 8, No. 16 (1987), pp. 67-89; IRSA sc, Krakow.

[4] Op. Cit. Kessler E. (2004), Bound by the bible: Jews, Christians and the Sacrifice of Isaac; tel. 138.

[5] Huizenga LA, The Aqedah at the End of the First Century of the Common Era: Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum, 4 Maccabees, Josephus' Antiquities, 1 Clemen; Journal for the study of the Pseudepigrapha Vol 20.2 (2010): 105-133; The Author(s), 2010. p. 8.

[6] Ibid, p. 9.

[7] Ibid, p. 15.

[8] The fourth book of the Maccabees, in The World English Bible, https://ebible.org/pdf/eng-web/eng-web_4MA.pdf

[9] Ibid, (17. 20-22): “These, therefore, having been sanctified through God, have been honored not only with this honor, but that also by their means the enemy didn't overcome our nation; and that the tyrant was punished, and their country purified. For they became the ransom to the sin of the nation; and the Divine Providence saved Israel, aforetime afflicted, by the blood of those pious ones, and the propitiatory death.”

[10] Feldman LH, Josephus as a Biblical Interpreter: The “ʿAqedah”; The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Jan., 1985), pp. 212-252; University of Pennsylvania Press.

[11] Ibid, p. 233.

[12] Flavius Josephus, The Antiquities of the Jews; Documenta Catholica Omnia; 1, 13.4.

[13] Op. Cit. Feldman, p. 237.

[14] Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, (1, 80-101): "Superstition could lead to such great evils."

[15] Op. Cit., Flavius Josephus, Book 5, Chapter 8.