In 2016 we went to visit the sacred site of Chavín de Huantar in Peru, the most important temple of the pre-Inca civilization of the Chavín. In this report we analyze the archaeological remains that have come down to us - starting from the Lanzón, the Stele Raimondi and the characteristic "nail-heads" - and the visionary cult that took place in the underground meanders of the temple.

di Marco Maculotti

Cover: vintage photo, Tello 1919 shipment

In an article-report published in the summer of 2021 in register no. 1 of “Golem”, the annual publication of the friends of La Società dello Sulfur, I described the ritual use of the psychotropic cactus commonly called San Pedro in the traditional context of Andean shamanism and especially in the area of Huancabamba, in the Piura region of northern Peru, near the border with Ecuador. In this plateau on which the Laguna Negra stands, considered sacred by the natives and above all by the healers locals that operate the shamanic healing of visitors with its waters, I personally took part in a nocturnal ritual session led by Don Feliciano, one of the best known shamans of the seeds Chasquero, whose contact I had made on the way to the North [1].

The use of this sacramental cactus it is very ancient in Peru, dating back to at least 2000 BC., as evidenced by the remains of cacti found in Las Aldas, and was also later known by the still little-known Chavín culture, once rulers almost entirely of present-day Peru. The priests of this population, which preceded the Incas by many centuries, officiated the cult of the jaguar-god at the temple complex of Chavín de Huantar — located more or less in the center of Peru, about 250 kilometers north of Lima — which I visited a few days before setting out on a journey through the Piura region in search of the vegetable sacrament and a medicine man available to officiate the rite according to the dictates of tradition. I was in a sense following in the footsteps of the anthropologist Mario Polia, who spent years "in the field" in the Andes and had narrated the shamanic rituals in which he had taken part in Huancabamba in his book The blood of the condor, halfway between ethnographic essay and travel diary, which I had brought in my suitcase during my trip to Peru in 2016 [2].

On the way to Huancabamba I took the opportunity to visit, a few kilometers west of Trujillo, the remains of Chan Chan, the very particular walled citadel which, before the Inca conquest, dominated the surrounding marshy area and constituted the capital of the Chimù kingdom, a mainly coastal civilization derived from the previous one of the Moche/Mochica; and, in the coastal desert near Trujillo, near the mountain of Cerro Blanco, the so-called Huacas of the Sun, the Moon and the witcho (“sorcerer”), sacred sites belonging precisely to the Moche, who carried out religious rituals and even human sacrifices in them, also attested by archaeologists.

Human sacrifices were also attested in a third sacred site visited by me on the road to Huancabamba, namely the already mentioned equally pre-Inca temple complex, although even more archaic than those belonging to the Moche and Chimu civilizations, of Chavín de Huantar, built and used by the homonymous Chavín civilization, which dominated the lands and above all the Peruvian coasts for a long period of time prior to the coming of the Incas, in a period that archaeologists have identified roughly between the end of the II millennium before our era and a few centuries before the year zero.

THE RAIMONDI STELE AND THE LANZÓN

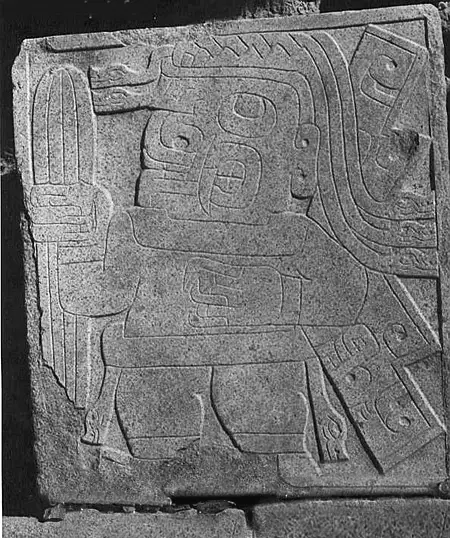

The temple of Chavín de Huantar, although already mentioned in the sixteenth-century chronicles of Pedro Cieza de León and then, between the end of the century and the first decades of the seventeenth century, by Toribio de Mogrovejo and Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa, was made known to the academic world from Italian Antonio Raymondi, who explored it from top to bottom in 1873. It is to him that we owe the discovery of the famous stele called precisely Stele Raimondi which, when viewed from an orientation, represents a terrifying deity wielding two staffs or sceptres with an elaborate headdress formed by snakes and scrolls. The same image, if turned upside down, appears completely different: the headdress becomes a stack of fanged and smiling faces while the face of the deity is transformed into the muzzle of a reptile, also smiling. Even the two sceptres held by the deity appear as a row of faces.

Even more central to the visual economy of the Chavín ritual cult is the so-called Lanzon, a finely sculpted megalithic sculpture of four and a half meters originally located in the basement of the temple, where the frenetic phases of the initiation rituals took place cult of the jaguar-god. The monolith had already been glimpsed by the first Spanish settlers who, dragging themselves into the reduced space of the underground where it was located, managed to see only its face with its menacing tusks and serpentine hair, surprisingly similar to that of the mythical ones Gorgons. The term Lanzon comes from Spanish 'Lanza', with reference to the characteristic shape of the sculpture which resembles an enormous spearhead made of diorite, a type of granite that is very difficult to work.

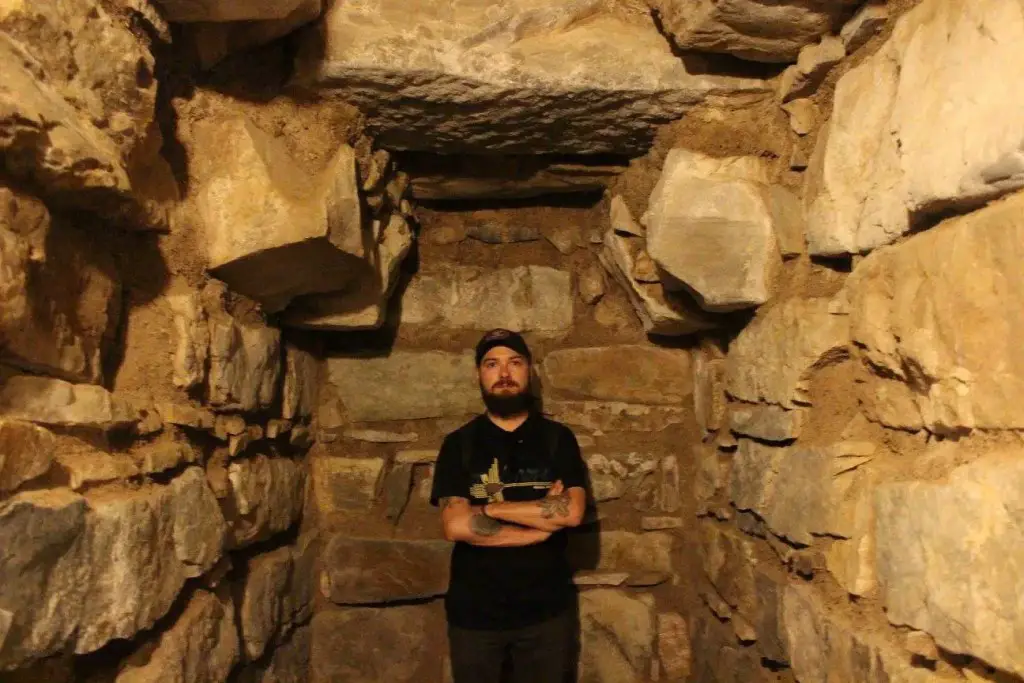

In the basement of the temple, according to Tello's hypothesis, the neophyte was made to enter an altered state of consciousness and then channeled his steps, through labyrinthine ways, towards a small underground square in which the aforesaid stele stood out which, like all those found on the site, depicts only partially anthropomorphic divine figures, characterized by the presence of long pointed fangs, similar to those of large cats considered sacred throughout pre-Columbian America. It is assumed that the statue was used to celebrate human sacrifices. On the front side of the support that held the monolith suspended, two deep parallel grooves carved into the rock are visible which, according to Tello, would have had the function of making the blood of the immolated victims flow up to a circular depression in the shape of a small basin, located above the head of the idol, and from this through other vertical channels until it touches its fanged jaws.

SAN PEDRO AND THE INCUBATION RITUALS

Another bas-relief represents the shamanic operator, also depicted with feline characteristics, while in one hand he holds the sacramental cactus and in the other a dagger with which to cut it. The cult of the Chavín, centered on the adoration of a feline-god and on the assumption of a psychotropic substance of a vegetable nature, seems to be a perfect double of the analogous one discovered in Mexico, chronologically placeable roughly around the same era in the cultural sphere Maya, where the shamans accessed the invisible world of the jaguar-god by taking on his appearance by ingesting an analogous sacrament, namely the psilocybin mushroom or of Peyote [3], another type of cactus extremely similar to the San Pedro, the use of which is documented starting from 4000 BC and moreover is still widespread today not only among the descendants of the Nahuatl and the Indians of the Plains such as the Navajo and the Sioux, but also further north , in certain tribal groups settled in present-day Canada such as the Winnebago, the Deleware and the Kaioka.

in underground of the Chavín complex, thanks to an exceptional drainage system, during the rainy season the water rushed through the channels creating a roaring sound, to the point that the temple seemed to roar like a jaguar: a perfect situation for the initiatory rites of incubation, which archaically were widespread not only in the Americas and among the so-called "primitives", but also in advanced societies, the Greeks above all, who ascribed these underground rites mainly to theApollonian cult bed [4]. The entheogenic effects of San Pedro they were in all probability amplified by the play of light/shadow created by the passage of torches held by the priests, present in one of the most famous representations of the site, as well as by music, songs and the repetition of ritual formulas.

JAGUARS AND DRAGONS

The jaguar often recurs in the typical representations of Chavín de Huantar: many sculptures have been recovered showing the transformation from a human head into that of a jaguar. Nonetheless, it is necessary to remember how in the Mexican area representations of the same type of divinity with feline characteristics can already be found several centuries earlier, among the Olmecs, as well as in present-day Colombia on the megalithic steles of civilization of San Agustín, as enigmatic as that of Chavín, author among other things of unique dolmens in the whole South American panorama.

Precisely with regard to the megalithic and more generally architectural aspect, a few notes can also be added on the temple complex of Chavin. According to archaeologists, it was used in a period between about 1100 BC and 500 BC. Examining it with my eyes, at first glance it made a bizarre impression on me, as the construction technique differs significantly from that of the much better known megalithic sites of the Cuzco Valley (Machu Picchu, Sacsayhuaman, Ollantaytambo, Pisaq, Q'enqo, Tambomachai, Puqara), who had received my vision in the previous weeks.

We take the opportunity to underline incidentally that, in the opinion of the writer, all the sites listed above are to be considered far more long-lived than the historical period of the Incas, as in the same Spanish chronicles the natives, questioned about it, attributed their erection to much more ancient populations, belonging to cycles of civilizations preceding the one to which the Incas and themselves belonged (the "Fourth Sun"), probably in the Third if not even in the Second [5].

According to the Andean tradition, in these protohistoric times Peru was inhabited by the so-called gentiles (“Gentiles”), a 'Christianized' denomination aimed at defining a mythical typology of antediluvian humanity similar to the Titans and Giants of the Mediterranean traditions, like the latter annihilated by the supreme god (in this case, Viracocha) due to their arrogance and impiety. On this subject, the tradition of the archaic Mediterranean and that still known today in the Andes find remarkable parallels [5] .

And the architectural and constructive similarities are also impressive, because the site of Chavín de Huantar, so different from the southern ones of the Cuzco Valley, recalls in a singular way some protohistoric sites of Greece, such as the equally enigmatic drakospito (“Dragon Houses”) of the island of Eubea (Èvia), which are traced back to a period between 1200 and 600 BC: roughly, therefore, to the same period that is attributed to the Chavín culture on the other side of the world. In turn, both have not negligible similarities with numerous prehistoric forts unearthed in Scandinavia, Ireland and the archipelagos north of Scotland, which can be traced back to the Iron Age, the Bronze Age or even, in some cases, to the Neolithic. The temple was built of white granite and black limestone, neither of which is found in close proximity to the site.

It will be noted, incidentally, that even the Celtic-Gaelic traditions on the one hand and the Germanic-Scandinavian traditions on the other handed down very similar beliefs regarding the titanic past humanities and their architectural legacies: likewise the farmers Andeans who considered these luoghi huaca [7], they too considered them imbued with an intense but dangerous sacral energy, intimately connected to a mythical characterization of these protohumanities of identical sign to what was agreed by the Peruvian tradition, as well as by the Mediterranean one.

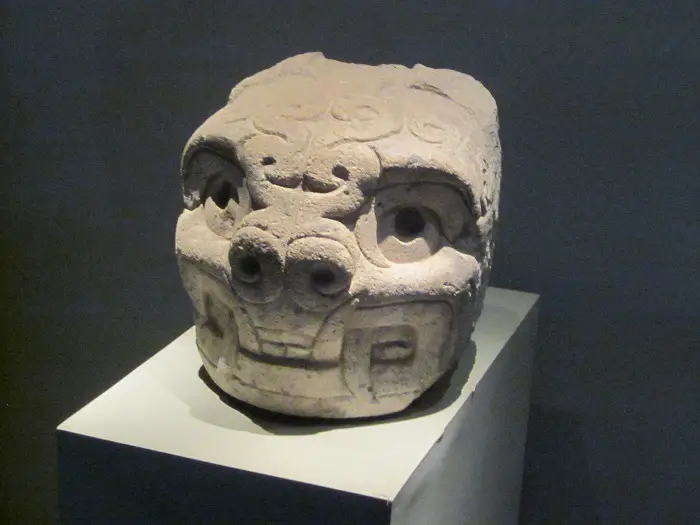

THE “NAIL-HEADS” OF THE CHAVÍN

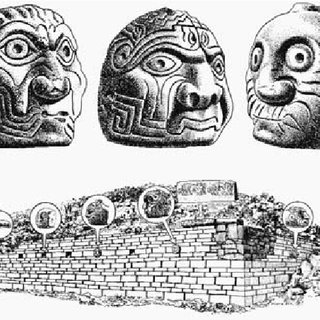

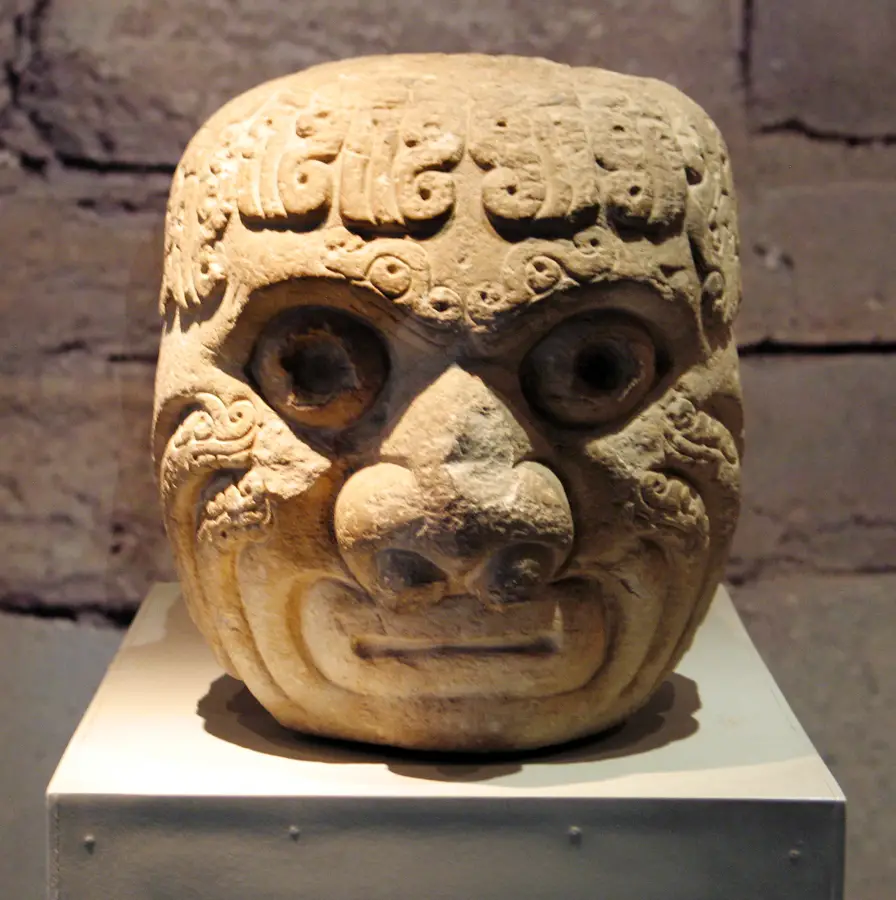

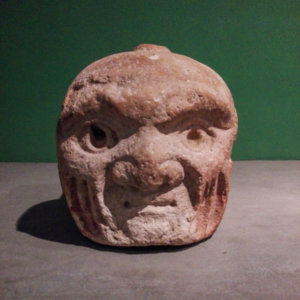

Some archaeologists have focused their attention on peculiar lithic heads emerged in large numbers from the excavations of the site of Chavín de Huantar, some of which are still today seated on the external walls while others can be viewed in the local museum, emphasizing their bizarre features and supposed deformities, which in their opinion would make them representations of the “degenerate” antediluvian bloodline which according to the Andean myth was turned into stone by celestial fire sent by Viracocha. Very similar sculptural examples also embellished the much more famous temple complex of Tiahuanaco [8], south of Lake Titicaca, in today's Bolivia, as well as, if we wanted to go further, in some of the ancient rock sanctuaries built by the Celtiberians, such as that of Roquepertuse [9], in which the heads of enemies killed in battle and others carved into the rock were hoisted above lithic or wooden lintels which, among other things, closely resemble those still visible today on the external walls of the Chavín temple.

All have an elongated structure on the back, the same one that was used to insert it like a nail into the walls intended for its display: hence their denomination used by the archaeologists of «heads-nails». It is believed that they were originally located atop the south, east and west walls of the Chavín temple, in a horizontal row and positioned evenly under carved stone cornices in low relief. Only one of these still remains on its original site.

Currently the National Museum of Chavín preserves about 100 complete or nearly complete heads. The main rocks used for their production were volcanic tuff (81%), limestone (15%) and sandstone (4%). González-Ramirez indicates that the choice of volcanic tuff is due to its abundance in the area, its good workability and its high porosity, which facilitate both its movement and the cutting work.

They feel representations of mythical beings, with anthropomorphic features (51%), zoomorphic (45%) (of felines and snakes) and ornithomorphs (4%) (of birds). Not infrequently, as also happens in the Stele Raimondi, the ophidian elements are found mixed with feline ones, primarily with the ever-present jaguar fangs, to underline in all probability the experience of "confusion" and "mixing" of the forms that the shaman, once he has access to the Underworld, experiences firsthand. Generally the eyes are represented as circular and very open and the felinomorphic mouth (of feline) with fangs, or sometimes ornithomorphic with a beak. Some have decorations of snakes, in the shape of hair, and protuberances that simulate crests above the head.

One of the peculiarities of these lithic heads are the lines that can be interpreted in the same way as facial tattoos of the type of those of the New Zealand Maori [10], a tribe which among other things was once dedicated to the ritual beheading of the enemy during wars and to the preservation of his skull in the manner of the ancient Siberians and Germans. Nonetheless the aforementioned lines can also be interpreted as labyrinthine lines, following the example of Babylonian demon-god Humbaba — the divine guardian of the “Cedar Forest” located in the “Life-Giving Mountain”” — typically depicted with a “labyrinthine face” reminiscent of intestines [11].

Other stone heads are more reminiscent of the Mayan and Aztec ones depicting skinless skulls, with sunken eyes and expressions now terrifying now smiling in an enigmatic way. Some bear a surprising resemblance, in their deformity and bizarreness, to some Sheela-na-gig Irish or to certain green man o gargoyles with a similar expression, widespread in countless medieval churches in the Celtic area, and perhaps even more to pumpkins and turnips carved on the occasion of the feast of the dead, that is to say the "ancestors" of today's Halloween pumpkins, representing "dead heads ”.

Julius Tello managed to identify and recover, between 1919 and 1941, a total of 42 heads initially embedded in the facade of the temple. To house these and other archaeological pieces Tello had set up a museum, but unfortunately these heads have all disappeared in theflood of 1945 that affected the archaeological site; which is why today only a few replicas of the original heads that were discovered by Tello can be viewed in the museum.

Later, during the excavations carried out on the site from the 60s to 2000, other heads were recovered. The latest discovery dates back to July 2013: archaeologists John Rick and Luis Guillermo Lumbreras have announced the discovery of two almost intact heads, in good condition, which were buried in a very narrow corridor and must have fallen together with the wall in which they were stuck, following an earthquake which is believed to have occurred around 200 AD They measure 103cm long by 39cm wide and 43cm high, and each weighs approximately 250kg.

Note:

[1] See MARCO MACULOTTI, On the trail of Andean shamanism. A healing ritual in northern Peru, on "Golem" n.1/2021.

[2] See MARIO POLIA, The blood of the condor. Shamans of the Andes, Xenia, 1997.

[3] See PETER T. FURST, Hallucinogens and culture. The sacramental drugs in the great Mesoamerican civilizations, Cesco Ciapanna publisher, 1981.

[4] See MARCO MACULOTTI, The Angel of the Abyss. Apollo, Avalon, the Polar Myth and the Apocalypse, Axis Mundi Editions, Milan-Soresina 2022.

[5] See MARCO MACULOTTI, Viracocha and the myths of origin of the Andean tradition, in "Atrium" n.1/2021, Pythagorean Last Supper Adytum; ID., Viracocha and the myths of the origins: creation of the world, anthropogenesis, foundation myths; Pachacuti: cycles of creation and destruction of the world in the Andean tradition.

[6] See ID., Antediluvian, giant, "gentle" humanity.

[7] See ID., “Altiplano”: the pangs of Pachamama and the Anima Mundi.

[8] See ID., The enigma of Tiahuanaco, cradle of the Incas and "Island of Creation" in Andean mythology.

[9] See J. LUIS MAYA GONZALES, Celts and Iberians in the Iberian PeninsulaJaca Book, 1999.

[10] See MARCO MACULOTTI, Secret History of New Zealand: From Oral Tradition to Genetic Analysis.

[11] See KAROLY KERENYI, In the labyrinthBollati Boringhieri, 2016.