A study of the symbolism of the double-headed ax (labrys), the spiral, the hourglass, the bull and the labyrinth, and their relationship with the annual path of the sun and especially with the solstices.

di Vanni Saponaro

We have probably lost the ability to interpret what a sign (which has become a symbol over time or perhaps designed to be) communicates. Today we can therefore only venture hypotheses, which is exactly what will be done in this short article. Many symbols are associated with generic solar cultures; the bull, the labrys and the spiral I am among them, as I am also the labyrinth, the wheel, the swastica, the triskelion and many others. Little is known about their ontogeny.

Today's difficulty in understanding what a symbol conveyed is probably due to an interruption in the oral transmission of knowledge related to the sphere of the sacred, a privileged, perhaps unique, route used in the past to transmit this type of knowledge. The definitive caesura occurred definitively with the advent of Christianity but it could have already occurred in the classical world (remember that Plato was considered the last of the initiates).

To try to understand and distinguish the solar origin of some symbols it is necessary to go back in time when the matrilineal and matrifocal culture linked to the cult of the Mother Goddess (Gimbutas, 1989), already dominant in the Mediterranean in prehistoric times, was replaced by a new patriarchal culture, dominated by weapons and war, centered around the male figure. This cultural transformation hypothesized by Gimbutas is made to coincide with the arrival of peoples who on several occasions arrived from Central-Eastern Europe and dominated the Mediterranean starting from the third millennium BC (Dumézil, 2003), a migratory hypothesis subsequently confirmed by recent genomic studies. These people, identified as Proto-Indo-Europeans, were warrior populations probably endowed with a hierarchical and patriarchal social organization.

However, the paradigm shift that took place in the Mediterranean at the hands of these Eurasian populations has not erased some typically Mediterranean cultural and symbolic solar aspects, prior to the invasion. This could mean two things: either that the Indo-Europeans have introjected the Mediterranean solar cult into their culture or that they already possessed it before. The second hypothesis would find an explanation in the Anatolian Neolithic migrations towards the north: the Indo-Europeans, having in any case had Neolithic origins, would have preserved some characteristics over time, thus denoting their belonging to the Mediterranean cultural substrate.

The decisive blow to the possible understanding of the pre-Indo-European Mediterranean culture and the symbolic world it proposed was inflicted by the Catholic religion, which brought about a real overturning of the cyclical thought that dominated for millennia. The new religion, through the introduction of an unprecedented linear time, has produced the concealment and transformation of the symbols that expressed the previous culture, linked to cosmic cycles (Saponaro, 2017).

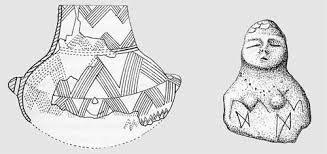

Among the solar symbols that have characterized both the pre-Indo-European and Indo-European Mediterranean cultures, including the peoples derived from them such as the Italics, there are certainly the bull, the spiral - found both in Neolithic and Bronze Age contexts - and a strange hourglass shape that sometimes looks like a butterfly, and which at other times is represented on various vase paintings and on small idols such as the body of human figures (figs. 1 and 2).

Both the bull and the labrys/hourglass and the labyrinth - the latter being considered a more recent variant of the spiral - are pre-existing symbols of Indo-European culture which will re-emerge, inextricably linked to each other, in the Mycenaean culture which replaces the Minoan one, which in turn has its roots in the final part of the Bronze Age on the island of Crete. Subsequently the same symbols, in particular the labrys and the labyrinth, no longer connected to each other, will also re-emerge throughout the Mediterranean basin within the main cultures that populated it.

La labrys it's a'“double-headed” ax which for the Mycenaeans seems to have had an exclusively cultic/ritual function [1]. The name of this ax could provide the etymology of the other central element of that culture, the labyrinth. According to this hypothesis the etymology of labyrinth would mean “palace of the double axe”.

It should be noted that the bipen, as a symbol, appears - as well as in Cretan art and mythology - also in African mythology in relation to the god Shango of the Yoruba culture, in that Thrace, in the Nuragic, Greek, Byzantine and in some cultures referable to the Italic peoples. The Romans will associate it with Janus, who we know is also the guardian of the two solstitial doors, which as we will see have a lot to do with our axe. In some cases the bipen is also associated with the bull: in fact, it appears between its horns in a painting on a Cretan vase and on a sarcophagus (figs. 3 and 4).

To understand where the double ax symbol could come from and therefore what it could symbolize, try to imagine building a rudimentary astronomical observatory driving a stake into the ground, what astronomers call one gnomon, one of the first astronomical instruments used by man (fig. 5). If one observed the shadow cast by the gnomon during an entire solar year, one would notice that it affects an area that has the shape of a double axe. Note that the figure that forms is enclosed by two opposing arches, or if you want by two horns opposing [2].

The two arcs are drawn from the extremity of the shadow of the pole between the two solstices: the winter one will project longer and more distant shadows from the gnomon, and therefore will form the furthest arc, while the summer one will produce the same arc shape, but closest and with opposite convexity. The handle of the ax is instead represented by the shadow that the pole projects between sunrise and sunset at the equinoxes. Naturally the figure that I have schematized must be contextualized in the natural condition in which the observation takes place; in fact the sunrise and the sunset are the apparent ones that depend on the orography of the place and on the latitude. That the shape of the great ax is related to the sun could also be confirmed by the two opposing spirals - also solar symbols - which can be observed in the Labrys in the photo, kept in the Herakleion museum (fig. 6).

even the bull symbol it has had numerous implications both in prehistoric and in proto-historical up to historical culture, in particular in the Latin and Greek one, where it plays a leading role. The kingship to the bull within the Cretan labyrinth could provide it with the very name of the Cretan monster: Minotaur in fact it combines the name of the famous king Minos(se) — which, considering his royal birth, may be considered a prefix of “king” — with the suffix taurusi.e. "bull". From this it can be deduced that for the Mycenaeans the Minotaur, therefore the solar bull-god, was considered a sort of king imprisoned in a labyrinth.

Also regarding the symbol of the labyrinth it is not easy to make a synthetic account, considering the symbolic and mysterious charge it conveys. Its distribution is almost ubiquitous in the world and its journey continues also within the Catholic culture (figs. 7 and 8). In its commonly known form it would seem to appear in the cultural imagination of man starting from the XNUMXnd millennium BC (Saward, sd).

It too is considered a solar symbol but, as with the others, no adequate explanation is given for this affiliation. It is hypothesized that its descendants derive from the symbol of the spiral, older than the labyrinth and closely linked to the sun. I believe that, through the solar symbolic acceptance of the proposed spiral (Cossard, 1996), one can also confirm its solar character through the association with the bull and the labrys.

To do this, it is necessary to imagine a man who, from a pre-established and fixed point, watches the sun rise on the horizon. After a few observations made from the same position, one would notice that the sun does not always rise at the same point on the horizon, but moves, little by little, towards north or south, on its annual journey [3]. Furthermore, rising in the sky, it completes a more or less high arc, depending on the season, which ends with its sinking below the horizon.

It was probably just these first observations that, together with those of the stars, provided the sense of cyclicality that has characterized human culture for tens of thousands of years. These "astronomical" measurements have certainly generated questions related to the path of the sun below the horizon, about the continuation of its path in the invisible part of the world. That's probably how it was born conception of "underworld", the world of the abyss, of the invisible, with all the implications on death, rebirth and the otherworldly that we find in many cultures and myths.

It is therefore possible to hypothesize that the rudimentary concentric spirals, both in the form of engravings and paintings, found in some prehistoric caves on rocks and walls and shelters, as well as in some tombs and House of Jana sardines, wanted to represent the path of the sun and therefore the cyclical nature of time. These primordial labyrinths were therefore not "labyrinthine" in the strict sense, but have subsequently become so. Their shape and the path they trace, as we have seen, could represent the path that takes the Sun back to its starting point. The duplication that in some cases is observed of the spiral in its double could symbolize one way and one way back, and the theme of birth and death it could therefore be related to the sun through its cyclical nature.

The evolution of the circular spiral shape into that of the square labyrinth that we know could have occurred between the end of the Neolithic and the advent of the metal ages; the first evidence of the labyrinth would be found in Galicia (Saward, sd) and would date back to the XNUMXnd millennium BC A labyrinthine shape was also found in the so-called “Palace of Nestor”, among the ruins of Pylos in the Peloponnese, and would seem to refer precisely to the primordial form of the palace of Knossos (Cordano, 1980) as seen by the newly arrived Mycenaeans. The tablet is dated 1200 BC (Aspesi, 2016).

On closer inspection, this evolution from a circular shape to a sharp edge can also be found in the "architectural" forms and can be trivially associated with the advent of metals and the corresponding tools. In fact, parallel to the actual temples with their squared off-ground architectural structures, also contemporary or slightly earlier places of worship in caves have evolved from typically rounded and circular shapes to squared shapes with right angles and walls.

The symbolic meaning of the labyrinth would be analogous to that of the spiral, and it has not lost the characteristic of a prison (the bull is imprisoned in the labyrinth) from which it is impossible to escape, just like the sun was in the spiral, forced to always walk the same path enclosed within the solstitial limits. For this reason the bull was probably chosen as the symbolic animal enclosed in the Cretan labyrinth: it is in fact the solar animal par excellence. The bull-solar god, common to many prehistoric cultures, remained so.

The Minotaur/bull-solar god is therefore imprisoned inside the labyrinth which symbolizes the path of the sun, in turn symbolized by the Labrys, the ritual ax which strongly characterizes the Minoan culture, through its labyrinthine shape. Here, according to my very modest interpretation, what could be the symbolic bond that inextricably links the Labrys, the Bull and the Labyrinth within the Minoan culture: it is a distinctly solar "character" and this is the meaning that hides the myth of the Minotaur.

NOTE:

[1] Since the double axes found in the excavations do not appear to have sharpness, they have been considered by archaeologists ceremonial objects.

[2] Horns are a topos of prehistoric Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures and are often associated with the sun and moon.

[3] Strangely we are taught that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. This notion is if not exactly wrong at least greatly simplified. In fact, the sun only rises in the east at the equinoxes. Dawn, the horticultural rising of the sun moves in a calendar year between southeast and northeast, between the winter and summer solstice respectively.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Aspesi, F. (2016). “The labyrinth at Amnisos”. Aion-ANNALI-l'Orientale-Department of Literary, Linguistic and Comparative Studies Linguistic section, P. 16.

Cordano, F. (1980). “The labyrinth as a graphic symbol of the city”. In Mélanges de l'Ecole française de Rome. Antiquité, volume 92, n°1 (p. pp. 7-15).

Cossard, G. (1996). “Astronomical significance of spiral engravings”, in 1996. Proceedings of the XVI Congress of the History of Physics and Astronomy (edited by Pasquale Tucci).

Daniele, V. (sd). “Etymology-of-the-word-labyrinth“. Taken from Italian etymology: https://www.etimoitaliano.it/2014/01/etimologia-della-parola-labirinto.html

Dumezil, G. (2003). The tripartite ideology of the Indo-Europeans. Rimini: The Circle.

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The language of the goddess.

Saponaro, V. (2017). The era of the end of ages. Taken from Academy: https://www.academia.edu/31054230/Lera_della_fine_delle_ere_pdf

Saward, J. (sd). The first labyrinths. Taken from labyrinthos: http://www.labyrinthos.net