Tag: Middle Ages

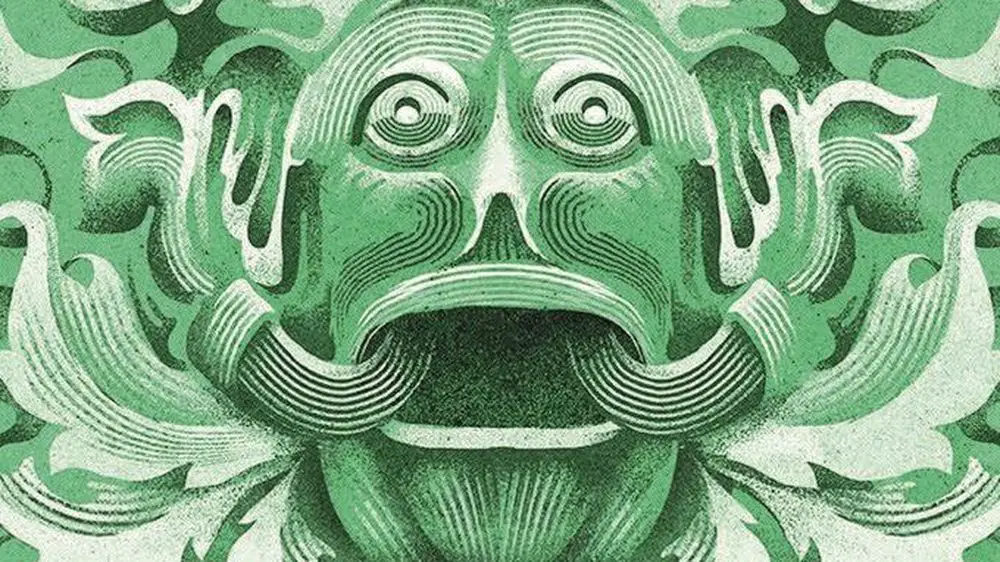

The true nature of the Green Man

Ornamental motif initially in medieval miniatures, then in British and Germanic Christian architecture, the symbol of the "Green Man" is a real mystery, as although apparently born in the Christian era it undoubtedly carries 'pagan' symbolisms on the perpetual rebirth of vegetative soul of nature and of the whole cosmos.

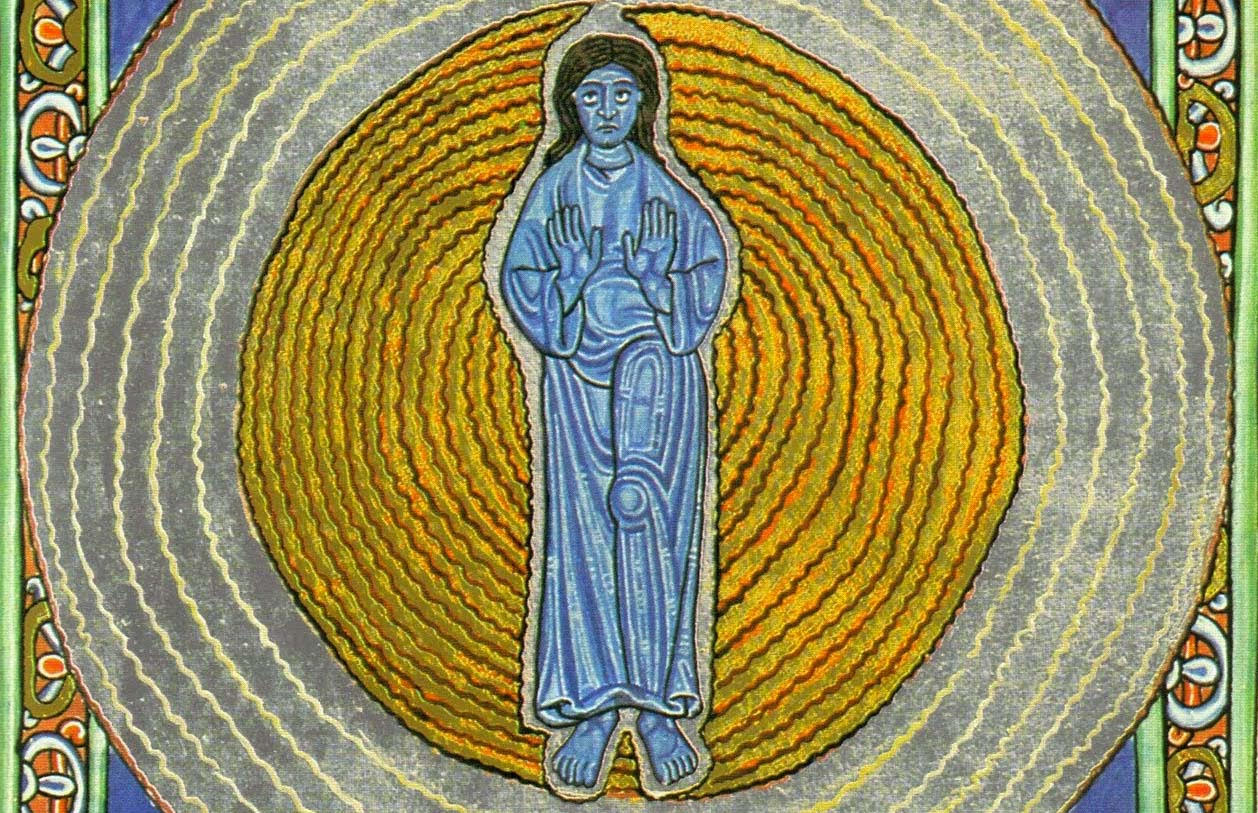

Hildegard of Bingen, the Sibyl of the Rhine

In the decline of a world ruled by men only, an intrepid nun with a warrior spirit does not hesitate to lash the consciences of popes and emperors. Mystic and prophetess, theologian and philosopher, leader and preacher, composer and doctor, that of Hildegard of Bingen is one of the most original voices of the twelfth century. Let's retrace the adventurous events together.

Considerations on the question of hierolanguage in the Middle Ages (I)

The true origin of verbal language is a mystery that is lost in the mists of the most remote past of mankind. This universal and transversal theme (which is linked to that of the arcane power of the word and in particular the evocation of Divine Names) in Western civilization has been the subject of speculative and theological reflection since the times of Greek philosophy, maintaining its centrality also in the philosophical culture of the Christian Middle Ages.

René Guénon: "The symbolism of the theater"

It can be said that the theater is a symbol of the manifestation, of which it expresses in the most perfect way possible the illusory character; and this symbolism can be considered either from the point of view of the actor, or from that of the theater itself. The actor is a symbol of the "Self", or rather of the personality, which manifests itself through an indefinite series of states and modalities, which can be regarded as so many different parts; and it should be noted the importance that the ancient use of the mask had for the perfect accuracy of this symbolism.

The Marvelous in the Middle Ages: the "mirabilia" and the apparitions of the "exercitus mortuorum"

An overview of how the Marvelous and the irrational survived the advent of Christianity in popular culture, with a particular focus on the apparitions of the dead and above all of the "furious army", the discussion of which will continue in second part of this comprehensive study

René Guénon: "On the meaning of carnival festivals"

The unsurpassed analysis by the French esotericist on the traditional meaning of Carnival, of the "world upside down" and of masquerades

The kidnappings of the Fairies: the "changeling" and the "renewal of the lineage"

Our "Magonia" cycle continues with an analysis of the tales of kidnappings of human beings by the "fairy people", with particular attention to the phenomenon known as "changeling", the kidnappings of babies and nurses, the hypothesis of "Renewal of the feeric lineage" and, finally, a confrontation with the so-called "alien abductions".

The Friulian benandanti and the ancient European fertility cults

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Luis Ricardo Falero, “Witches going to their Sabbath", 1878).

Carlo Ginzburg (born 1939), a renowned scholar of religious folklore and medieval popular beliefs, published in 1966 as his first work The Benandanti, a research on the Friulian peasant society of the sixteenth century. The author, thanks to a remarkable work on a conspicuous documentary material relating to the trials of the courts of the Inquisition, reconstructed the complex system of beliefs widespread up to a relatively recent era in the peasant world of northern Italy and other countries, of Germanic area, Central Europe.

According to Ginzburg, the beliefs concerning the company of the benandanti and their ritual battles against witches and sorcerers on the Thursday nights of the four tempora (Her hand, imbol, Beltain, Lughnasad), were to be interpreted as a natural evolution, which took place far from the city centers and from the influence of the various Christian Churches, of an ancient agrarian cult with shamanic characteristics, widespread throughout Europe since the Archaic age, before the spread of the Jewish religion - Christian. Ginzburg's analysis of the interpretation proposed at the time by the inquisitors is also of considerable interest, who, often displaced by what they heard during interrogation by the benandanti defendants, mostly limited themselves to equating the complex experience of the latter with the nefarious practices of witchcraft. Although with the passing of the centuries the tales of the benandanti became more and more similar to those concerning the witchcraft sabbath, the author noted that this concordance was not absolute:

"If, in fact, the witches and sorcerers who meet on Thursday night to give themselves to" jumps "," fun "," weddings "and banquets, immediately evoke the image of the sabb - that sabb that the demonologists had meticulously described and codified, and the inquisitors persecuted at least since the mid-400th century - nonetheless exist, among the gatherings described by benandanti and the traditional, vulgate image of the diabolical sabbath, evident differences. In these cEverywhere, apparently, homage is not paid to the devil (in whose presence, indeed, there is no mention of it), faith is not abjured, the cross is not trampled, there is no reproach of the sacraments. At the center of them is a dark ritual: witches and sorcerers armed with sorghum reeds who juggle and fight with benandanti provided with fennel branches. Who are these benandanti? On the one hand, they claim to oppose witches and sorcerers, to hinder their evil designs, to heal the victims of their hexes; on the other hand, not unlike their presumed adversaries, they claim to go to mysterious nocturnal gatherings, of which they cannot speak under pain of being beaten, riding hares, cats and other animals. "

—Carlo Ginzburg, "I benandanti. Witchcraft and agrarian cults between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries», Pp. 7-8