This article reconstructs the relevant coincidences between various finds from the Indus Valley Civilization and the myths and rituals of the later Vedic culture.

di Alessandro Lorenzoni

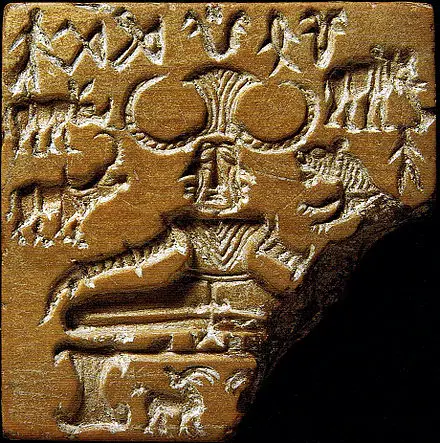

Cover: pashupati seal

Perhaps the most significant find from the Indus Valley Civilization is the seal found at Mohenjo-daro showing a three-faced deity seated in a yogic position and surrounded by various animals: a rhinoceros, a buffalo, an elephant, a man, a tiger and, below, two antelopes. The meaning of this mute relic – conserved in the National Museum of New Delhi – could be at the origin of some myths of the Vedic civilization, subsequent to that of Mohenjo-daro. Until now the two civilizations have been considered separately; but a thorough analysis of the Mohenjo-daro seal elements suggests a close relationship between them. So let's look at each of these elements.

1. The deity and the animals

The three-faced deity sitting in a yogic position is surrounded by various herbivorous animals. The Vedic deity Prajāpati sends forth all genitures (or creatures) only to have them stay with him for his śrī [1] and his food:

ŚBK, 4, 9, 1, 1. In fact, Prajāpati – given the genitures – was thought of as emptied. Therefore, furthermore, the genitures became distant (from him) – they did not stay with him, for laśrī, for the food.

ŚBK, 4, 9, 1, 2. He (Prajāpati) reflected, “I (am) exhausted. Furthermore, the desire – for which I have issued the geniture [2] – it was not satisfied (attained) for me: they (genitures, ŚBM, 3, 9, 1, 2) became distant (from me) – they do not stay with me, for śrī, for food! ”. “How and how can I further increase myself and the parents they can get back together next to me – can they stay with me, for śrī, for food?”

Prajāpati is thus at the center of all parentages – which return close to him and are thus his food [3]:

PB, 17, 10, 2. Prajāpati issued the genitures. Emitted, they went away from him. (…) Thus, (Prajāpati) went (vyavait) to their center. Their they came back close to him. They surrounded him.

PB, 21, 2, 1. Prajāpati issued the genitures. Emitted, they went away from him, scared: "He will devour us". He said, “What come back close to me! Indeed, I will devour you, in such a way that – devour – more numerous [abundant] you will generate”. To them – they had told him: “Promise!” – He promised, (with the melody) with the final ṛtá. (With the melody) with the ending ī, (Prajāpati) (le) devoured (āvayat). (With the melody) with the triple ending, (le) prompted to generate (prājanayad).

Prajāpati's genitures are only the food and so they are like the herds for the Devās:

JB, 2, 254. (The thousand cows) said: "Indeed, I am afraid of the decrease." “No,” said (the Devās), “Indeed, we will devour you, in such a way that – eaten, drunk – you will not decrease for us". To him – “Indeed, that (you) promise me!” – they promised, (with the melody) with the ending ṛtá. (with melody) with the ending ī, (lo) they devoured (āvayan). (With melody) with triple ending, and lo they induced to generate e for him they did the ákṣiti [4].

With the exception of the tiger, the herbivorous animals around the deity of Mohenjo-daro are all bent on four feet:

KS, 29, 9. Prajāpati issued the genitures. They had gone away from him. They had gone up. He wanted them: “They can come back close to me”. He was burning. He immolated himself, for the sacrifice. Their they came back close to him. They were scared of him. They were bent. Therefore, the herds are folded.

The Vedic myths narrate how Índra becomes with a face (with a mouth) in every direction and thus devours all the begettings of Prajāpati:

TB, 2, 2, 10, 6 and 7. Became Prajāpati, he (Índra) devoured (āvayat) the parentage. They didn't stay with him for food. (…) Having become with a face (with a mouth) in every direction, (Índra) devoured them. In this way, in fact, the parentage remained with him, for food.

Índra shaves his head and thus becomes with a face (or with a mouth) in every direction – like Prajāpati: «He who, knowing thus, makes himself shaved, became Prajāpati, devour the parentage. The parents stay with him, for food. He becomes a devourer" (TB, 2, 2, 10, 7). Prajāpati's food flies away from him in every direction:

JB, 3, 256. Prajāpati gave out the food. Frightened by the decrease, (food) went away in directions. He (Prajāpati) wished, “I can get the food”. He saw a melody. With this (melody): “He stayed, here! It stayed, here!”, (Prajāpati) got food, from all directions.

Not only is the deity of the Mohenjo-daro seal surrounded by animals, but it has three faces for as many directions. The TB further relates how Índra – the rājanyá [5] of the Devās – is installed by Prajāpati:

TB, 2, 2, 10, 1-3. Prajāpati emitted Índra – the youngest of the Devās. He ordered him: “Go! Let (thou) be the ádhipati [6] of these Devās!”. The Devas said to him, “Who are you? In fact, we are better than you." He said (to Prajāpati): "'Who are you?', the Devās said to me, 'Indeed, we are better than you'". Then, at that time, fervor – which is in the Sun – was here in Prajāpati. (Índra) said to him: “May (you) give it to me! Then I will become the ádhipati of these Devās”. "The who can I be,” said (Prajāpati), “(having) given it?”. “You can be”, said he (Índra), “what you say (= About)". Indeed, About it is the name (of) Prajāpati. (…) Having made a golden disc (rukmáṃ), (Prajāpati) put it on him. In this way, Índra became the ádhipati of the Devās. He who thus knows becomes the ádhipati of peers.

A statue from Mohenjo-daro shows a king or priest with a discus on his forehead:

Similar myths to those about Prajāpati and his parentage extend to Índra and his Devās:

JB, 2, 100. Prajāpati issued the genitures. He issued, they did not respect him. He wished, "I can attain respect in these parentages." (…) In this way, in fact, they respected him. In fact, moreover, the Devā did not respectno Indra. He went to Prajāpati: "Indeed, the Devās do not respect me." (Prajāpati) gave him (vyadadhāt) the sacrifice (for) respect. (…) In this way, in fact, the Devā respected him.

Índra is the main Indo-European deity; while Prajāpati could be a deity of Dravidian origin. Índra's power over genitures (or creatures) comes from Prajāpati:

PB, 16, 4, 1. Prajāpati issued the genitures. They did not stay with him, for the śraíṣṭhya [7]. He – having attracted the juice (rasaṃ) of these directions and parentages, made (he had) a garland – put (it) on himself. In this way, the parentage remained with him, for the śraíṣṭhya.

PB, 16, 4, 3. He (Prajāpati) wished, “Índra may be the best (śreṣṭhaḥ) in my parentage”. She put the wreath on him. In this way, the parentage remained with Índra, for the śraíṣṭhya – seeing (in Índra) the adornment they saw in his father.

The genitures – only for him and not for themselves – rise up against Prajāpati:

PB, 7, 5, 1 and 2. Prajāpati wished: “I can be many. I can generate”. He remained – afflicted, unhappy. (…) Thus (with this āmahīyava [8]), he issued these genitures. He issued, they were happy. (…) Issued, they they had gone away from him. He took (…) their prāṇā (breaths). Taken in the prāṇās, them they came back still close to him. He gave (…) them again (back, punaḥ) the prāṇā. They had risen up against him (or had shown aversion to him). He broke (…) their anger. In this way, in fact, they stayed with him, for the śraíṣṭhya.

2. The deity and the tiger

The animals around the seal deity of Mohenjo-daro are on four feet – with the exception of a tiger. She the latter is about to devour the divinity, after having grabbed her with her front paws. Prajāpati in the Vedic myths is about to be devoured by his son Agní (Fire), who is Death: Prajāpati begets again and thus saves himself from Agní:

ŚBM, 2, 2, 4, 7. Offered, Prajāpati e generated e he saved himself from Agní, Death about to devour (him). He who, knowing thus, offers the agni-hotrá, begets that prájāti [9] which Prajāpati begat; so also saves himself from Agní, Death about to devour (him).

The tiger – with its mostly ocher hair – is the aspect of Death:

“It stretches (for the rājanyá) the skin of a tiger. (…) The tiger is this aspect (this form, MS, 4, 4, 4) of Death» (TB, 1, 7, 8, 1).

3. The deity and the antelopes

The seal deity of Mohenjo-daro appears to be seated upon two antelopes. In the Vedic consecration ritual, the anointed (dīkṣitá) sits upon the skin of a sable antelope (kṛṣṇājiná). The black and white hairs of a sable antelope's skin are day and night:

JB, 2, 62. That (Sun) that burns is this dīkṣitá. (…) The shape of a sable antelope's skin is day and night. The day is the shape of white (of the skin). The night, of black (of the skin). (…) He (the púruṣa in the disk of the Sun) is the prāṇá. He is Indra. He is Prajāpati. He is the dīkṣitá.

JB, 2, 63. He who is this púruṣa in the eye is this dīkṣitá. (…) As the shape of the skin of a sable antelope is the black and white (of the eye). The white (of the eye) is the form of the white (of the skin). Black (of the eye), of black (of the skin). (…) He (this púruṣa in the eye) is the prāṇá. He is Indra. He is Prajāpati. He is the dīkṣitá.

The dīkṣitá is above the skin of a sable antelope and so it is beyond the black and white hairs: from day and night:

JB, 3, 357. As, being established in the plane of a chariot (rathopasthe tiṣṭhan), he can gaze upon the wheels, so, being established in the world of the Sun (ādityaloke tiṣṭhan), he gazes at day and night.

The yogic position is proper both to the deity (recognizable by the three faces) and to the sages and ascetics.

Conclusions

The animals in the seal of the Indus Valley civilization may have been replaced – in the myths about Prajāpati – by genitures and herds:

PB, 7, 10, 13. Prajāpati sent forth the herds. Issued, them they were gone from him. She was addressing them with this melody. Their remained with him. They became submissive.

PB, 6, 7, 19. Prajāpati sent forth the herds. Issued, them they were gone from him, hungry. He gave them a prastará [10] – food. Their they came back close to him. Therefore, the prastará is stirred slightly by the adhvaryú[11]. For the herds come back close to the agitated straw (for food).

Is the seal deity going to devour animals or is only Prajāpati in Vedic myths a devourer? The two deities may have both inspired the vegetarianism of Indian civilization. A Harappan tablet may in fact show a sage or ascetic sitting in a yogic position distracting himself from killing a buffalo:

Perhaps the Vedic texts could contain an example of the lucidity of Harappa's sages and ascetics: the genitures remain with Prajāpati and are only the food for Prajāpati and so the herds and multitudes are situated before the brāhmaṇá and the kṣatrá [12] and are only the food for the brāhmaṇá and for the kṣatrá:

ŚBK, 4, 9, 1, 3. Offered with this (ekādaśínī [13]), (Prajāpati) increased (or filled) himself again. The parentages they came back together close to him – they stayed with him, for śrī, for food. Offered, he became better (váśīyān).

ŚBK, 4, 9, 1, 10. Therefore, the brāhmaṇá (is he who) has more power over the herds. As the herds become situated front (to him), situated in the mouth of him (asya, of the brāhmaṇá).

ŚBK, 4, 9, 1, 14. In fact, furthermore, the víśaḥ (the multitudes, the peoples) are the food. It renders the food in front (in front, purástād) of the kṣatrá. Therefore, the kṣatríya is the devourer (of the víśaḥ). As food (= le víśaḥ) becomes situated front (to him), situated in the mouth of him (asya, of the kṣatrá).

ŚBM, 6, 1, 2, 25. [Tāṇḍya:] “Indeed, the kṣatríya is the devourer. The víś (the multitude, the people) is the food. Where (yátra) the food becomes more numerous [abundant] than the devouring one, the rāṣṭrá [14] becomes prosperous, (the rāṣṭrá) increases”.

If the multitudes are for the kṣatrá, then the herds are for the brāhmaṇá. The brāhmaṇá on the herds instructs [15] the kṣatrá about the multitudes and thus the multitudes – before the mouth [16] of the kṣatrá – are like the herds. As the herds are to the brāhmaṇá, so the multitudes are to the kṣatrá [17]. The deity of the brāhmaṇá and the kṣatrá can only be Prajāpati and the brāhmaṇá and the kṣatrá are both only for Prajāpati:

KB, 12, 8. So, in fact, and with the Brahmaṇá and with the kṣatrá, and with the kṣatrá and with the Brahmaṇá, Prajāpati came to grasp (or encircle) from both sides, to obtain the food [18].

The Vedic texts could express an esoteric knowledge: the animals around the deity of Mohenjo-daro could be his food – just as the genitures are just the food for Prajāpati. The brāhmaṇá and the kṣatrá are ultimately like Prajāpati: the herds and multitudes are only a food set before them.

«If lightning struck cattle, the people were not distressed. It used to be said, “The lord has slaughtered for himself among his own food. Is it yours? is it not the lord's? He is hungry; he kills for himself” [19]. "

The oldest Vedic texts - such as the TB and the PB - could testify to the relationship between the original culture of the Indus Valley and that of the Indo-European peoples in India. In conclusion, Prajāpati may be the deity of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa and a source of inspiration for later Vedic myths.

Sources index:

ŚBM – Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa, version of Mādhyandina – Weber (A.), The White Yajurveda, The Çatapatha-Brâhmaṇa in the Mâdhyandina-Çâkhâ, Berlin-London: 1855, II.

ŚBK - Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa, version of Kāṇva - Caland (W.), The Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa in the Kāṇvīya recension, Lahore: 1926, I; 1939, II.

PB - Pañcaviṃśa-Brāhmaṇa - Śāstrī (AC), The Tāṇḍyamahābrāhmaṇam, Benares: 1935, I; 1936, II.

JB – Jaiminīya-Brāhmaṇa – Vīra (R.), Candra (L.), Jaiminīya-Brāhmaṇa of the Sāmaveda, Nagpur: 1954 [Reprint Delhi: 1986].

TB – Taittirīya-Brāhmaṇa – Thiṭe (GU), Taittirīya-Brāhmaṇa, New Delhi: 2012, I and II.

KS – Kāṭhaka-Saṃhitā – Schroeder (L. von), Kâṭhakam. Die Saṃhitâ der Kaṭha-Çâkhâ, Leipzig: 1900, I; 1909, II; 1910, III.

MS - Maitrāyaṇi-Saṃhitā - Schroeder (L. von), Maitrâyaṇî Saṃhitâ. Die Saṃhitâ der Maitrâyaṇîya-Çâkhâ, Leipzig: 1881, I; 1883, II; 1885, III; 1886, IV.

KB - Kauṣītaki-Brāhmaṇa - Lindner (B.), Das Kauṣîtaki-Brâhmaṇa, Jena: 1887, I.

Note:

[1] śrī is prosperity, excellence.

[2] Also ŚBM, 7, 5, 2, 6 and 7. «In the beginning, Prajāpati was here, unique. He wished: "I can emit food. I can generate”. He created herds from prāṇā (senses). (…) Emitted the food (= the herds), if he (it) placed it – from front to back – in himself ».

[3] All the myths about Prajāpati and the genitures and herds are collected in my site"Vedic fragments".

[4] Akṣiti is inexhaustibility. The deity of Mohenjo-daro has an erect member. Prajāpati emits his genitures from the member: 'He issued the genitures from the member. Therefore, these (genitures) are plentiful. Since she issued them from the member» (TB, 2, 2, 9, 6). The vaíśya is issued by the member of Prajāpati and thus is prolific: “Therefore, furthermore, (the vaíśya) is prolific. Because (Prajāpati) emitted it from the belly – from the member» (JB, 1, 69). For the vaíśya is the food for the brāhmaṇá and for the rājanyá: «Therefore, the vaíśya – devoured – has not decreased. As it is issued from the member» (PB, 6, 1, 10). So also the vaisyaè like the herds: "Therefore, the herds – eaten, cooked – have not diminished. Because it makes them established in the matrix (yónau)» (ŚBM, 7, 5, 2, 2).

[5] The rājanyá (or rājā) is the king.

[6] The ádhipati is the lord.

[7] śraíṣṭhya is superiority, supremacy. Also JB, 3, 218. «Prajāpati sent out the herds. Emitted, they went away from him. He wished, “The herds may not go away from me. They can come back to me." (…) So (with this melody), he trapped them. Across the śraiṣṭhya, subdued (or dominated, upāgṛhṇāt) them. They were with him."

[8] The āmahīyava is a ritual melody.

[9] The prájāti is the generation.

[10] The prastará is a bundle of stalks or hay.

[11] The adhvaryú is the one who recites the ritual formulas.

[12] The brāhmaṇá and the kṣatrá (or kṣatríya) are the priestly power and the sovereign power: the two powers.

[13] The ekādaśínī is an offering of eleven herds or victims.

[14] The rāṣṭrá is the kingdom.

[15] Bṛ́has-páti – the brāhmaṇá – installs Índra – the kṣatrá – on the Devās – on the víś. Also MS, 2, 2, 6. «Welĺhas-pati li (= the Devā) induced to sacrifice, with this (offering), for consonance. Thus, (the Devas) they came back together towards Indra; they were compliant to Indra".

[16] Also MS, 4, 3, 8. «For him (for the kṣatrá), place close to the mouth, for the food, the víś with the driver of a cart at the head».

[17] So, together with the herds, like herds, men are for the rājanyá – for the work of the rājanyá (ŚBK, 7, 1, 3, 1 and 2).

[18] Literally, he was grabbing from both sides, getting food ('nnādyaṃ parigṛhṇāno 'varundhāna ait).

[19] C. Callaway, Unkulunkulu; or, the Tradition of Creation as existing among the Amazulu, London: 1868, I, 60.